Modern Art and Modern Movement: Images of Dance in American Art, C

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Durham Research Online

Durham Research Online Deposited in DRO: 24 January 2017 Version of attached le: Published Version Peer-review status of attached le: Peer-reviewed Citation for published item: Harding, J. (2015) 'European Avant-Garde coteries and the Modernist Magazine.', Modernism/modernity., 22 (4). pp. 811-820. Further information on publisher's website: https://doi.org/10.1353/mod.2015.0063 Publisher's copyright statement: Copyright c 2015 by Johns Hopkins University Press. This article rst appeared in Modernism/modernity 22:4 (2015), 811-820. Reprinted with permission by Johns Hopkins University Press. Additional information: Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-prot purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in DRO • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Please consult the full DRO policy for further details. Durham University Library, Stockton Road, Durham DH1 3LY, United Kingdom Tel : +44 (0)191 334 3042 | Fax : +44 (0)191 334 2971 https://dro.dur.ac.uk European Avant-Garde Coteries and the Modernist Magazine Jason Harding Modernism/modernity, Volume 22, Number 4, November 2015, pp. 811-820 (Review) Published by Johns Hopkins University Press DOI: https://doi.org/10.1353/mod.2015.0063 For additional information about this article https://muse.jhu.edu/article/605720 Access provided by Durham University (24 Jan 2017 12:36 GMT) Review Essay European Avant-Garde Coteries and the Modernist Magazine By Jason Harding, Durham University MODERNISM / modernity The Oxford Critical and Cultural History of Modernist VOLUME TWENTY TWO, Magazines: Volume III, Europe 1880–1940. -

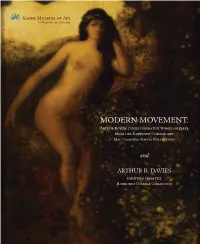

Modern Movement: Arthur Bowen Davies Figurative Works on Paper from the Randolph College and Mac Cosgrove-Davies Collections

AT MODERN MOVEMENT: Arthur Bowen Davies Figurative Works on Paper from the Randolph College and Mac Cosgrove-Davies Collections and ARTHUR B. DaVIES Paintings from the Randolph College Collection 1 2COVER: Arthur B. Davies, 1862-1928, Nixie, 1893, oil on canvas, 6 x 4 in. Gift of Mrs. Robert W. Macbeth, 1950 MODERN MOVEMENT: Arthur Bowen Davies Figurative Works on Paper from the Randolph College and Mac Cosgrove-Davies Collections January 18–April 14, 2013 Curated by Martha Kjeseth-Johnson and Mac Cosgrove-Davies Arthur B. Davies, ca. 1908. Gertrude Käsebier, photographer. AT 3 Introduction Martha Kjeseth-Johnson, Director Maier Museum of Art at Randolph College Arthur B. Davies (1862-1928) was an artist and primary curator of the groundbreaking Armory Show of 1913, credited with bringing modern art to American audiences. The Maier Museum of Art at Randolph College (formerly Randolph-Macon Woman’s College) is home to sixty-one works by Davies, many of which have never been exhibited. Malcolm Cosgrove-Davies, great-grandson of Arthur B. Davies and owner of over 300 Davies pieces, has contributed a selection of works from his collection which will also be on view to the public for the first time.Modern Movement: Arthur Bowen Davies Figurative Works on Paper from the Randolph College and Mac Cosgrove-Davies Collections focuses on figurative works, many depicting dancers in various poses. We are pleased to present this exhibition on the centennial anniversary year of what was officially billed asThe International Exhibition of Modern Art but commonly referred to as the Armory Show due to its location at New York’s 69th Regiment Armory on Lexington Avenue in Manhattan. -

Finding Aid for the John Sloan Manuscript Collection

John Sloan Manuscript Collection A Finding Aid to the Collection in the Helen Farr Sloan Library & Archives, Delaware Art Museum The John Sloan Manuscript Collection is made possible in part through funding of the Henry Luce Foundation, Inc., 1998 Acquisition Information Gift of Helen Farr Sloan, 1978 Extent 238 linear feet Access Restrictions Unrestricted Processed Sarena Deglin and Eileen Myer Sklar, 2002 Contact Information Helen Farr Sloan Library & Archives Delaware Art Museum 2301 Kentmere Parkway Wilmington, DE 19806 (302) 571-9590 [email protected] Preferred Citation John Sloan Manuscript Collection, Helen Farr Sloan Library & Archives, Delaware Art Museum Related Materials Letters from John Sloan to Will and Selma Shuster, undated and 1921-1947 1 Table of Contents Chronology of John Sloan Scope and Contents Note Organization of the Collection Description of the Collection Chronology of John Sloan 1871 Born in Lock Haven, Pennsylvania on August 2nd to James Dixon and Henrietta Ireland Sloan. 1876 Family moved to Germantown, later to Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. 1884 Attended Philadelphia's Central High School where he was classmates with William Glackens and Albert C. Barnes. 1887 April: Left high school to work at Porter and Coates, dealer in books and fine prints. 1888 Taught himself to etch with The Etcher's Handbook by Philip Gilbert Hamerton. 1890 Began work for A. Edward Newton designing novelties, calendars, etc. Joined night freehand drawing class at the Spring Garden Institute. First painting, Self Portrait. 1891 Left Newton and began work as a free-lance artist doing novelties, advertisements, lettering certificates and diplomas. 1892 Began work in the art department of the Philadelphia Inquirer. -

(312) 443-3625 [email protected] [email protected]

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE January 14, 2013 MEDIA CONTACTS: Erin Hogan Chai Lee (312) 443-3664 (312) 443-3625 [email protected] [email protected] THE ART INSTITUTE HONORS 100-YEAR RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN PICASSO AND CHICAGO WITH LANDMARK MUSEUM–WIDE CELEBRATION First Large-Scale Picasso Exhibition Presented by the Art Institute in 30 Years Commemorates Centennial Anniversary of the Armory Show Picasso and Chicago on View Exclusively at the Art Institute February 20–May 12, 2013 Special Loans, Installations throughout Museum, and Programs Enhance Presentation This winter, the Art Institute of Chicago celebrates the unique relationship between Chicago and one of the preeminent artists of the 20th century—Pablo Picasso—with special presentations, singular paintings on loan from the Philadelphia Museum of Art, and programs throughout the museum befitting the artist’s unparalleled range and influence. The centerpiece of this celebration is the major exhibition Picasso and Chicago, on view from February 20 through May 12, 2013 in the Art Institute’s Regenstein Hall, which features more than 250 works selected from the museum’s own exceptional holdings and from private collections throughout Chicago. Representing Picasso’s innovations in nearly every media—paintings, sculpture, prints, drawings, and ceramics—the works not only tell the story of Picasso’s artistic development but also the city’s great interest in and support for the artist since the Armory Show of 1913, a signal event in the history of modern art. BMO Harris is the Lead Corporate Sponsor of Picasso and Chicago. "As Lead Corporate Sponsor of Picasso and Chicago, and a bank deeply rooted in the Chicago community, we're pleased to support an exhibition highlighting the historic works of such a monumental artist while showcasing the artistic influence of the great city of Chicago," said Judy Rice, SVP Community Affairs & Government Relations, BMO Harris Bank. -

Exhibition of the Arthur Jerome Eddy Collection of Modern Paintings and Sculpture Source: Bulletin of the Art Institute of Chicago (1907-1951), Vol

The Art Institute of Chicago Exhibition of the Arthur Jerome Eddy Collection of Modern Paintings and Sculpture Source: Bulletin of the Art Institute of Chicago (1907-1951), Vol. 25, No. 9, Part II (Dec., 1931), pp. 1-31 Published by: The Art Institute of Chicago Stable URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/4103685 Accessed: 05-03-2019 18:14 UTC JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at https://about.jstor.org/terms The Art Institute of Chicago is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Bulletin of the Art Institute of Chicago (1907-1951) This content downloaded from 198.40.29.65 on Tue, 05 Mar 2019 18:14:34 UTC All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms EXHIBITION OF THE ARTHUR JEROME EDDY COLLECTION OF MODERN PAINTINGS AND SCULPTURE ARTHUR JEROME EDDY BY RODIN THE ART INSTITUTE OF CHICAGO DECEMBER 22, 1931, TO JANUARY 17, 1932 Part II of The Bulletin of The Art Institute of Chicago, Volume XXV, No. 9, December, 1931 This content downloaded from 198.40.29.65 on Tue, 05 Mar 2019 18:14:34 UTC All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms No. 19. -

The Biomechanics of the Tendu in Closing to the Traditional Position, Pli#233

University of South Florida Scholar Commons Graduate Theses and Dissertations Graduate School January 2013 The iomechB anics of the Tendu in Closing to the Traditional Position, Pli#233; and Relev#233; Nyssa Catherine Masters University of South Florida, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarcommons.usf.edu/etd Part of the Engineering Commons Scholar Commons Citation Masters, Nyssa Catherine, "The iomeB chanics of the Tendu in Closing to the Traditional Position, Pli#233; and Relev#233;" (2013). Graduate Theses and Dissertations. http://scholarcommons.usf.edu/etd/4825 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Biomechanics of the Tendu in Closing to the Traditional Position, Plié and Relevé by Nyssa Catherine Masters A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science in Mechanical Engineering Department of Mechanical Engineering College of Engineering University of South Florida Major Professor: Rajiv Dubey, Ph.D. Stephanie Carey, Ph.D. Merry Lynn Morris, M.F.A. Date of Approval: November 7, 2013 Keywords: Dance, Motion Analysis, Knee Abduction, Knee Adduction, Knee Rotation Copyright © 2013, Nyssa Catherine Masters DEDICATION This is dedicated to my parents, Michael and Margaret, who have supported me and encouraged -

The Artist and the American Land

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Sheldon Museum of Art Catalogues and Publications Sheldon Museum of Art 1975 A Sense of Place: The Artist and the American Land Norman A. Geske Director at Sheldon Memorial Art Gallery, University of Nebraska- Lincoln Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/sheldonpubs Geske, Norman A., "A Sense of Place: The Artist and the American Land" (1975). Sheldon Museum of Art Catalogues and Publications. 112. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/sheldonpubs/112 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Sheldon Museum of Art at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Sheldon Museum of Art Catalogues and Publications by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. VOLUME I is the book on which this exhibition is based: A Sense at Place The Artist and The American Land By Alan Gussow Library of Congress Catalog Card Number 79-154250 COVER: GUSSOW (DETAIL) "LOOSESTRIFE AND WINEBERRIES", 1965 Courtesy Washburn Galleries, Inc. New York a s~ns~ 0 ac~ THE ARTIST AND THE AMERICAN LAND VOLUME II [1 Lenders - Joslyn Art Museum ALLEN MEMORIAL ART MUSEUM, OBERLIN COLLEGE, Oberlin, Ohio MUNSON-WILLIAMS-PROCTOR INSTITUTE, Utica, New York AMERICAN REPUBLIC INSURANCE COMPANY, Des Moines, Iowa MUSEUM OF ART, THE PENNSYLVANIA STATE UNIVERSITY, University Park AMON CARTER MUSEUM, Fort Worth MUSEUM OF FINE ARTS, BOSTON MR. TOM BARTEK, Omaha NATIONAL GALLERY OF ART, Washington, D.C. MR. THOMAS HART BENTON, Kansas City, Missouri NEBRASKA ART ASSOCIATION, Lincoln MR. AND MRS. EDMUND c. -

Cubism in America

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Sheldon Museum of Art Catalogues and Publications Sheldon Museum of Art 1985 Cubism in America Donald Bartlett Doe Sheldon Memorial Art Gallery Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/sheldonpubs Part of the Art and Design Commons Doe, Donald Bartlett, "Cubism in America" (1985). Sheldon Museum of Art Catalogues and Publications. 19. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/sheldonpubs/19 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Sheldon Museum of Art at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Sheldon Museum of Art Catalogues and Publications by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. RESOURCE SERIES CUBISM IN SHELDON MEMORIAL ART GALLERY AMERICA Resource/Reservoir is part of Sheldon's on-going Resource Exhibition Series. Resource/Reservoir explores various aspects of the Gallery's permanent collection. The Resource Series is supported in part by grants from the National Endowment for the Arts. A portion of the Gallery's general operating funds for this fiscal year has been provided through a grant from the Institute of Museum Services, a federal agency that offers general operating support to the nation's museums. Henry Fitch Taylor Cubis t Still Life, c. 19 14, oil on canvas Cubism in America .".. As a style, Cubism constitutes the single effort which began in 1907. Their develop most important revolution in the history of ment of what came to be called Cubism art since the second and third decades of by a hostile critic who took the word from a the 15th century and the beginnings of the skeptical Matisse-can, in very reduced Renaissance. -

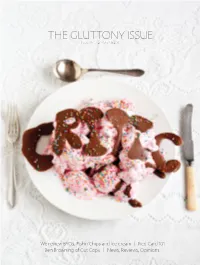

THE GLUTTONY ISSUE Issue 04 – 21St March 2011

THE GLUTTONY ISSUE Issue 04 – 21st March 2011 We review BYOs, Fish‘n’Chips and Ice cream | Red Card 101 Ben Browning of Cut Copy | News, Reviews, Opinions. Critic Issue 04 – 1 Critic Issue 04 – 2 Critic – Te Arohi PO Boc 1436, Dunedin (03) 479 5335 [email protected] www.critic.co.nz contents Editor: 5 – Editorial Julia Hollingsworth Designer: 6 – Letters to the Editor Andrew Jacombs Ad Designer: 7 – Notices Kathryn Gilbertson News Editor: 8 – Snippets Gregor Whyte News Reporters: 10 – News Aimee Gulliver, Lozz Holding 18 – The Inaugural BYO review Feature Writers: BYOs are becoming an integral part of student life. Charlotte Greenfield, We review the best and worst of the bunch. Josh Hercus, Phoebe Harrop, 21 – The Great and Glorious Annual Critic Siobhan Downes Sub Editor: Fush & Chup Review Lisa McGonigle Speaks for itself really. Feature Illustrator: Tom Garden 24 – We all scream for ice cream Music Editor: Critic reviews ice cream. Num num. Sam Valentine Film Editor: 26 – Red Card 101; an introduction to, and critical Sarah Baillie Books Editor: appraisal of, a Dunedin student tradition. Sarah Maessen We talk Red Cards: the themes, the crazy stuff that goes down, Theatre Editor: and what the Proctor thinks of them. Jen Aitken Food Editor: 30 – In Memoriam Niki Lomax Games Editor: 31 – Opinion Toby Hills Fashion Editor: 38 – Profile Mahoney Turnbull Critic interviews Ben Browning of Cut Copy Art Editor: Hana Aoake 40 – Summer Lovin’ And a whole heap of lovely volunteers 41 – Review Music, Film, Art, Fashion, Food, Games, Theatre, Books Planet Media (03) 479 5361 53 – Comics [email protected] www.planetmedia.co.nz 55 – OUSA Page Advertising: Kate Kidson, Tim Couch, Dave Eley, Critic is a member of the Aotearoa Student Press Association (ASPA). -

Download Lot Listing

IMPRESSIONIST & MODERN ART POST-WAR & CONTEMPORARY ART Wednesday, May 10, 2017 NEW YORK IMPRESSIONIST & MODERN ART EUROPEAN & AMERICAN ART POST-WAR & CONTEMPORARY ART AUCTION Wednesday, May 10, 2017 at 11am EXHIBITION Saturday, May 6, 10am – 5pm Sunday, May 7, Noon – 5pm Monday, May 8, 10am – 6pm Tuesday, May 9, 9am – Noon LOCATION Doyle New York 175 East 87th Street New York City 212-427-2730 www.Doyle.com Catalogue: $40 INCLUDING PROPERTY CONTENTS FROM THE ESTATES OF IMPRESSIONIST & MODERN ART 1-118 Elsie Adler European 1-66 The Eileen & Herbert C. Bernard Collection American 67-118 Charles Austin Buck Roberta K. Cohn & Richard A. Cohn, Ltd. POST-WAR & CONTEMPORARY ART 119-235 A Connecticut Collector Post-War 119-199 Claudia Cosla, New York Contemporary 200-235 Ronnie Cutrone EUROPEAN ART Mildred and Jack Feinblatt Glossary I Dr. Paul Hershenson Conditions of Sale II Myrtle Barnes Jones Terms of Guarantee IV Mary Kettaneh Information on Sales & Use Tax V The Collection of Willa Kim and William Pène du Bois Buying at Doyle VI Carol Mercer Selling at Doyle VIII A New Jersey Estate Auction Schedule IX A New York and Connecticut Estate Company Directory X A New York Estate Absentee Bid Form XII Miriam and Howard Rand, Beverly Hills, California Dorothy Wassyng INCLUDING PROPERTY FROM A Private Beverly Hills Collector The Collection of Mr. and Mrs. Raymond J. Horowitz sold for the benefit of the Bard Graduate Center A New England Collection A New York Collector The Jessye Norman ‘White Gates’ Collection A Pennsylvania Collection A Private -

Russian Museums Visit More Than 80 Million Visitors, 1/3 of Who Are Visitors Under 18

Moscow 4 There are more than 3000 museums (and about 72 000 museum workers) in Russian Moscow region 92 Federation, not including school and company museums. Every year Russian museums visit more than 80 million visitors, 1/3 of who are visitors under 18 There are about 650 individual and institutional members in ICOM Russia. During two last St. Petersburg 117 years ICOM Russia membership was rapidly increasing more than 20% (or about 100 new members) a year Northwestern region 160 You will find the information aboutICOM Russia members in this book. All members (individual and institutional) are divided in two big groups – Museums which are institutional members of ICOM or are represented by individual members and Organizations. All the museums in this book are distributed by regional principle. Organizations are structured in profile groups Central region 192 Volga river region 224 Many thanks to all the museums who offered their help and assistance in the making of this collection South of Russia 258 Special thanks to Urals 270 Museum creation and consulting Culture heritage security in Russia with 3M(tm)Novec(tm)1230 Siberia and Far East 284 © ICOM Russia, 2012 Organizations 322 © K. Novokhatko, A. Gnedovsky, N. Kazantseva, O. Guzewska – compiling, translation, editing, 2012 [email protected] www.icom.org.ru © Leo Tolstoy museum-estate “Yasnaya Polyana”, design, 2012 Moscow MOSCOW A. N. SCRiAbiN MEMORiAl Capital of Russia. Major political, economic, cultural, scientific, religious, financial, educational, and transportation center of Russia and the continent MUSEUM Highlights: First reference to Moscow dates from 1147 when Moscow was already a pretty big town. -

Guide to the Michigan Dance Archives: Harriet Berg Papers UP001608

Guide to the Michigan Dance Archives: Harriet Berg Papers UP001608 This finding aid was produced using ArchivesSpace on June 11, 2018. English Describing Archives: A Content Standard Walter P. Reuther Library 5401 Cass Avenue Detroit, MI 48202 URL: https://reuther.wayne.edu Guide to the Michigan Dance Archives: Harriet Berg Papers UP001608 Table of Contents Summary Information .................................................................................................................................... 3 History ............................................................................................................................................................ 4 Scope and Content ......................................................................................................................................... 4 Arrangement ................................................................................................................................................... 6 Administrative Information ............................................................................................................................ 6 Related Materials ........................................................................................................................................... 7 Controlled Access Headings .......................................................................................................................... 7 Collection Inventory ......................................................................................................................................