TOCC0479DIGIBKLT.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Century Later

The Hebrew University of Jerusalem The National Library of Israel Faculty of Humanities Music Department Jewish Music Research Centre Leonid Nevzlin Center for the Research of Pro Musica Hebraica (USA) Russian and Eastern European Jewry A Century Later Concert of Music by Composers of the Saint Petersburg Society for Jewish Folk Music On the Occasion of the Centennial of the Society’s Foundation Performers: Sivan Rotem, soprano Gilad Hildesheim, violin Jascha Nemtsov, piano Weintraub Hall, The National Library of Israel Thursday, January 8, 2009, 8:00 PM התכנית Program יואל אנגל ניגון חב ד" Joel Engel Chabader melody ( -1868 1927) פריילעכס Freilechs (1868-1927) לכינור ופסנתר for violin and piano אומרים ישנה ארץ Omrim yeshnah eretz לקול ופסנתר for voice and piano לזר סמינסקי אגדה עברית Lazare Saminsky Hebrew Fairy Tale ( -1882 1959) ריקוד שבת Danse rituelle du Sabbath (1959–1882) לפסנתר for piano שיר השירים Shir hashirim רחלינה Rachelina אומר ר ' אלעזר Omar Rabbi Eleazar לקול ופסנתר for voice and piano משה מילנר בחדר Moshe Milner In kheyder ( -1883 1953 ) לקול ופסנתר for voice and piano (1883-1953) אלכסנדר קריין קפריצ' ו עב רי Alexander Krein Caprice hebraïque ( -1883 1951) לכינור ופסנתר for violin and piano (1883-1951) יוסף אחרון וריאציות על נושא יהודי Joseph Achron Symphonic Variations on a Jewish ( -1886 1943) " אל יבנה הגליל " ”Theme “El yivneh hagalil (1943–1886) שישה קטעים Six pieces from the מתוך הסוויטה ליל םיד Childrens’ Suite לפסנתר for piano אלול בשדרה ( קנצונטה ) (Elul zum Garten (Canzonetta אין א קליינעם שטיבלה In a kleynem shtibele לקול ופסנתר for voice and piano אלת רו ריקודי Dance Improvisation שיר ערש עברי Hebrew Lullaby סוויטה מ תוך " סטמפניו Suite from the music for הכנר (" על פי שלום עליכם ) Stempenyu the Fiddler לכינור ופסנתר (after Shalom Aleichem) for violin and piano ניגון Hebrew Melody לקול , פסנתר וכינור for voice, violin and piano ההה טקסטי The Texts יואל אנגל Joel Engel אְמִרי : ֶיְָנ ֶאֶר ( שאול טשרניחובסקי ) Omrim yeshna eretz (by Shaul Tchernichovsky), Op. -

Jascha Nemtsov• “The Scandal Was Perfect”

Jascha Nemtsov “The Scandal Was Perfect” Jewish Music in the Works of European Composers Well into the 19th century, Jewish music went largely unnoticed in Euro- pean culture or was treated dismissively. Russian composers wrote the first chapter of musical Judaica. At the start of the 20th century, a Jewish national school of music was established in Russia; this school later in- fluenced the work of many composers in Western Europe. Since the Holocaust, Jewish music is understood less as folk music, it has become a political and moral symbol. The parties of the Hasidim where they merrily discourse on talmudic problems. If the entertainment runs down or if some- one does not take part, they make up for it by singing. Melodies are invented... a wonder-rabbi... suddenly laid his face on his arms, which were resting on the table, and remained in that position for three hours while everyone was silent. When he awoke he wept and sang an entirely new, gay, military march. Franz Kafka, 29 November 19111 What particularly impressed Kafka at a gathering of a Hasidic community at their rabbi’s home is typical for traditional Judaism: Religion and music are so tightly intertwined that reading and praying are conducted only in song. The first Hebrew grammar, De accentibus et orthographia linguae Hebraicae, by the Stuttgart humanist Johannes Reuchlin (1455–1522), was published in Alsatian Ha- genau in 1518. Reuchlin focused on the Hebrew Bible and included as well the motifs – Biblical cantillations – with which it was chanted by the European (Ashkenazi) Jews. This marked the first appearance of these motifs outside the Jewish community as well as the first time that they were transcribed into European musical notation.2 Music that had hitherto fulfilled only a ritual purpose thus became the subject of aca- demic discourse. -

Music from the Archive of Lazare Saminsky

YIVO INSTITUTE FOR JEWISH RESEARCH PRESENTS JEWISH SONGS AND DANCES: Music from the Archive of Lazare Saminsky SIDNEY KRUM YOUNG ARTISTS CONCERT SERIES In Partnership with Temple Emanu-El · 5th Avenue at 65th Street, NYC June 21, 2017 · 7:00pm PROGRAM The Sidney Krum Young Artists Concert Series is made possible by a generous gift from the Estate of Sidney Krum. In partnership with Temple Emanu-El. Saminsky, Hassidic Suite Op. 24 1-3 Saminsky, First Hebrew Song Cycle Op. 12 1-3 Engel, Omrim: Yeshnah erets Achron, 2 Hebrew Pieces Op. 35 No. 2 Saminsky, Second Hebrew Song Cycle Op. 13 1-3 Saminsky, A Kleyne Rapsodi Saminsky, And Rabbi Eliezer Said Engel, Rabbi Levi-Yitzkah’s Kaddish Achron, Sher Op. 42 Saminsky, Lid fun esterke Saminsky, Shir Hashirim Streicher, Shir Hashirim Engel, Freylekhs, Op. 21 Performers: Mo Glazman, Voice Eliza Bagg, Voice Brigid Coleridge, Violin Julian Schwartz, Cello Marika Bournaki, Piano COMPOSER BIOGRAPHIES Born in Vale-Gotzulovo, Ukraine in 1882, LAZARE SAMINSKY was one of the founding members of the Society for Jewish Folk Music in St. Petersburg – a group of composers committed to forging a new national style of Jewish classical music infused with Jewish folk melodies and liturgical music. Saminksy’s teachers at the St. Petersburg conservatory included Rimsky-Korsakov and Liadov. Fascinated with Jewish culture, Saminsky went on trips to Southern Russia and Georgia to gather Jewish folk music and ancient religious chants. In the 1910s Saminsky spent a substantial amount of time travelling giving lectures and conducting concerts. Saminsky’s travels brought him to Turkey, Syria, Palestine, Paris, and England. -

Herzlian Zionism and the Chamber Music of the New Jewish School, 1912-1925 Erin Fulton

Q&A How did you become involved in doing research? I first began to do some musicological research around the age of 11 or 12 when I became curious about the musical traditions of a nearby sect of Holdeman Mennonites. Those first inquiries led me to become interested in the larger tradition of Anglo-American hymnody, and shape-note and dispersed-harmonic music in particular, which remains my primary research interest. How is the research process different from what you expected? The unusual resources that turn out to be helpful constantly surprise me. I About Erin Fulton always expected my research to draw primarily on books and sheet music, but correspondence and ephemera have proven increasingly useful to my HOMETOWN recent endeavors. Lane County, Kan. What is your favorite part of doing research? MAJOR I am a bibliophile at heart and love the smell and touch of old books. Musicology Working with 19th-century tune books at Spencer Research Library has become one of my fondest memories of KU. ACADEMIC LEVEL Senior RESEARCH MENTOR Ryan Dohoney Assistant Professor of Musicology Herzlian Zionism and the chamber music of the New Jewish School, 1912-1925 Erin Fulton The stated goals of the St. Petersburg scholarship has emphasized ease presenting compositions inspired Society for Jewish Folk Music—the of performance in encouraging by Russian Jewish folk music as organization around which the New chamber music composition during an expression of Herzlian Zionism. Jewish School of composition arose— these years. While smaller works By programming newly-written focused on the creation of opera and doubtless presented reduced fiscal works alongside canonic chamber large-scale choral and symphonic and logistical challenges, two political pieces, these composers drew on works. -

The Influence of Klezmer on Twentieth-Century Solo And

THE INFLUENCE OF KLEZMER ON TWENTIETH-CENTURY SOLO AND CHAMBER CONCERT MUSIC FOR CLARINET: WITH THREE RECITALS OF SELECTED WORKS OF MANEVICH, DEBUSSY, HOROVITZ, MILHAUD, MARTINO, MOZART AND OTHERS Patricia Pierce Card B.M., M.M. Dissertation Prepared for the Degree of DOCTOR OF MUSICAL ARTS UNIVERSITY OF NORTH TEXAS December 2002 APPROVED: John Scott, Major Professor and Chair James Gillespie, Minor Professor Paul Dworak, Committee Member James C. Scott, Dean of the College of Music C Neal Tate, Dean of the Robert B. Toulouse School of Graduate Studies Card, Patricia Pierce, The influence of klezmer on twentieth-century solo and chamber concert music for clarinet: with three recitals of selected works of Manevich, Debussy, Horovitz, Milhaud, Martino, Mozart and others. Doctor of Musical Arts (Performance), December 2002, 60 pp., 35 titles. The secular music of the Eastern European Jews is known today as klezmer. Klezmer was the traditional instrumental celebratory music of Yiddish-speaking Ashkenazi Jews who eventually populated the Pale of Settlement, which encompassed modern-day Poland, Lithuania, Ukraine, Belarus and Romania. Due to the rise of oppression and expulsion, many klezmer musicians or klezmorim immigrated to the United States between 1880 and the early 1920s. These musicians found work in klezmer bands and orchestras as well as Yiddish radio and theater. Some of the most influential klezmorim were clarinetists Naftule Brandwein and Dave Tarras who helped develop an American klezmer style. While the American style flourished, the popularity of pure klezmer began to diminish. As American-born Jews began to prefer the new sounds of big band and jazz, klezmer was considered old-fashioned and was in danger of becoming a lost art form. -

The Jewish Experience in Classical Music: Shostakovich and Asia

The Jewish Experience in Classical Music The Jewish Experience in Classical Music: Shostakovich and Asia Edited by Alexander Tentser The Arizona Center for Judaic Studies Publication Series 1 The Jewish Experience in Classical Music: Shostakovich and Asia, Edited by Alexander Tentser This book first published 2014 Cambridge Scholars Publishing 12 Back Chapman Street, Newcastle upon Tyne, NE6 2XX, UK British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Copyright © 2014 by Alexander Tentser and contributors All rights for this book reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the copyright owner. ISBN (10): 1-4438-5467-0, ISBN (13): 978-1-4438-5467-2 TABLE OF CONTENTS Preface ....................................................................................................... vii Alexander Tentser Acknowledgements .................................................................................... xi Introduction .............................................................................................. xiii A Legacy of Honor and Risk in Jewish Music Janet Sturman Part I: Shostakovich Dmitri Shostakovich and Jewish Music: The Voice of an Oppressed People .......................................................................................................... 3 Alexander Tentser Self-Imagery and Resilience: -

Songs from St. Petersburg

Songs from St. Petersburg a selection of the finest pieces by the Society of Jewish Folk music Sovali, soprano and Paul Prenen, piano Programme Moshe Milner (1886-1953) Tsen Kinderlider fun I.L. Perets for voice and piano Viglid (Cradle Song) Ketsele, shtil (Pussycat, Quiet) A gute nacht (Good Night) Der foygl (The Bird) Der shifer (The Skipper) Breytele (Bread Roll) Tantz, tantz, meydele, tantz (Dance, Dance, Girl, Dance) Der jeger (The Hunter) Bal-shpil (Ball Game) Oyfn grinem bergele (On the Green Mountain) Alexander Veprik (1899-1958) Dances, op.13 for piano (1927-1928) Kaddish, for voice and piano, Op. 6 Two Jewish Songs, for voice and piano, Op. 8 Sayt gesunterheyt (Bless You) Spatziren saynen mir gegangen (We went out strolling) - intermission - Mikhail Gnesin (1883-1957) Jewish Songs, Op. 37 Yad anuga haita la (Her hand was tender) Pesenka Mariamnyi (Song of Mariamne) Shir hashirim (From the Song of Songs) Der soyne ba di toyern (The Enemy is at the Gates) Joseph Achron (1886-1943) Excerpts from Children’s Suite, Op. 57 (1923) for piano Two Songs, Op. 52 Yom, yom ani holech limonech (Everyday I go to your house) (Fichmann) Canzonetta (Avram ben Jizchak) Alexander Krein (1883-1951) Incidental Music Na Pokajannoi Tsepi (Penalty Chain) (L. Perets) for piano Voloch (Bessarabian Piece) Svadebnii March (Wedding March) Two Jewish Songs, Op. 39 Viglid (Cradle Song) May (May) --------------------------------------- (programme subject to modifications) 1 Programme Notes In 1908 a group of Jewish composers in St.-Petersburg, Russia, founded the Society for Jewish Folk Music. The society “was meant to be a meeting place for young talented Jewish composers interested in composing classical Jewish music” (J. -

A Hebrew Liederabend an Evening of Hebrew Song Tuesday, June 4, 2019

A Hebrew Liederabend An Evening of Hebrew Song Tuesday, June 4, 2019 ANNE E. LEIBOWITZ MEMORIAL CONCERT Program 6:00pm Pre-Concert Lecture Including music by 7:00pm Concert JOSEPH ACHRON JOEL ENGEL Performed by ALEXANDER KREIN ILANA DAVIDSON PAUL BEN-HAIM RAPHAEL FRIEDER OFER BEN-AMOTS ELIZABETH SHAMMASH and poetry by YEHUDI WYNER and guest artist RONN YEDIDIA SHAUL TCHERNICHOVSKY AVIGDOR HAMEIRI Devised by YEHUDA HALEVI NEIL W. LEVIN LEAH GOLDBERG RACHEL HAYIM NAHMAN BIALIK This event is part of the Smithsonian Year of Music. and others… YIVO INSTITUTE FOR JEWISH RESEARCH in the Center for Jewish History 15 WEST 16TH STREET · NYC PROGRAM INTERMISSION אומרים: ישנה ארץ | THEY SAY THERE IS A LAND נעמי שמר | Music by Naomi Shemer | 1930-2004 שאול טשרניחובסקי | Words by Shaul Tchernichovsky | 1875-1943 כיבוי אורות | LIGHTS OUT נעמי שמר | Music and Words by Naomi Shemer | 1930-2004 אומרים: ישנה ארץ | THEY SAY THERE IS A LAND מנחם ויזנברג | Arranged by Menachem Wiesenberg | 1950- יואל אנגל | Music by Joel Engel | 1868-1927 שאול טשרניחובסקי | Words by Shaul Tchernichovsky | 1875-1943 שיר ליקינתון | THE HYACINTH רבקה גוילי | Melody by Rivka Gwily שני מכתבים | TWO LETTERS לאה גולדברג | Words by Lea Goldberg | 1911-1970 יואל אנגל | Music by Joel Engel | 1868-1927 מנחם ויזנברג | Arranged by Menachem Wiesenberg | 1950- אביגדור המאירי | Words by Avigdor Hameiri | 1890-1970 הנך יפה רעיתי | BEHOLD, THOU ART FAIR גלות | IN EXILE ידידיה אדמון | Music by Yedidiya Admon | 1894-1982 היינריך שליט | Music by Heinrich Schalit | 1886-1976 שיר השירים | Words -

View the Evening's Program

DECEMBER 13, 2017 YIVO Institute for Jewish Research PRESENTS A YIDDISH LIEDERABEND — AN EVENING OF YIDDISH SONG — Devised and directed by Neil W. Levin ANNE E. LEIBOWITZ MEMORIAL CONCERT Tuesday Evening, December 13, 2017 Ida Rae Cahana, SOPRANO Elizabeth Shammash, MEZZO -SOPRANO Raphael Frieder, BARITONE Simon Spiro, TENOR Yehudi Wyner, PIANO CAMEO APPEARANCE: Robert Paul Abelson COVER: M. Milner, sheet music cover, vocal suite, 10 Children’s Songs for singer and piano, words by Y. L. Peretz, 1921. YIVO Archives. INTRODUCTION by NEIL W. LEVIN OR MOST OF US in the twenty-first century, allusions to “Yiddish song” have come typically if not F ipso facto to connote the popular, folk, quasi-folk, theatrical and other entertainment, and even commercial realms. Rarely now, especially outside circumscribed Yiddishist circles, do unmodified ref- erences to Yiddish song evoke association with the artistically cultivated, classical vocal genre known as Lieder, or ‘art song’—the intimate, introspective expressive medium that interprets, animates, and musically reflects as well as explicates serious poetry. Yet, classically oriented Yiddish song recitals such as this evening’s presentation—whether in appropriately modest public recital and chamber music venues or in the Liederabend context of domestic, quasi-salon social gatherings—were once commonplace components of Jewish cultural life in cosmopolitan environments; and nowhere more so than in the New York area. The German word Lied (pl., Lieder) translates generically in musical terms simply as ‘song’. The precise German equivalent of ‘art song’ is Kunstlied (as opposed, for example, to Volkslied for folksong), but that term is not actually invoked in general references to the ‘art song’ genre with which we are concerned here. -

TFG- La Nova Escola Jueva

I Treball Fi de grau La Nova Escola Jueva Una renaixença cultural Estudiant: Isaac Bachs Viñuela Especialitat/ Àmbit/Modalitat: Interpretació CiC- Violí Director/a: Miguel Simarro Grande Curs: 2016-2017 Vistiplau del director/a del Treball EXTRACTE TRILÍNGÜE The present work aims to explain the elements that led to the birth of a jewish cultural renaissance in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, as well as its development and subsequent influence on key composers of western music, such as Shostakovich and Prokofiev. Thereby, this work is widely documented from a printed bibliography of renowned jewish musicologists, such as Israel Adler and Abraham Idelssohn, as well as works made from the point of view of the performer, such as those made by pianists Jascha Nemtsov and Alexander Tentser, among others. Thanks to this work, I have found out that the New Jewish School was a stylistic embryo that later crystallized into the works of Shostakovich and Prokofiev, among others, and that, on the other hand, its members and repertoire have gone through an undeserved oblivion. El presente trabajo quiere explicar los factores que propiciaron el nacimiento de un renacer cultural judío a finales de siglo XIX y principios del XX, así como su desarrollo i la incidencia posterior en los compositores cruciales de la música occidental, como son Shostakovich i Prokofiev. Para ello, este trabajo está documentado ampliamente a partir de bibliografía impresa de musicólogos judíos especializados de gran nombre, como son Israel Adler y Abraham Idelssohn, así como de trabajos hechos desde la perspectiva del intérprete, como son los realizados por los pianistas Jascha Nemtsov y Alexander Tentser, entre otros. -

Download Program

Byron Schenkman Friends season four 2016-2017 page 1 Tickets start at $52 SEATTLE CHAMBER MUSIC 2017 SEASON SOCIETY JAMES EHNES Artistic Director WINTER FESTIVAL // JANUARY 20-29 BOX OFFICE SUMMER FESTIVAL // JULY 3-29 (206) 283-8808 seattlechambermusic.org ILLSLEY BALL NORDSTROM RECITAL HALL at Benaroya Hall Dragonfly Nutrition Bars Energy, nutrition, and happiness. • Made with raw nuts, • Nutritious and tasty organic dried fruits, and egg white protein • Made in Kirkland, WA from raw nuts • Fits perfectly into paleo, and organic dried gluten-free, and raw fruits all sourced in food diets the USA for fans of Byron Schenkman & Friends 10% OFF Coupon code: FRIENDOFBYRON www.dragonflybars.com Welcome to the fourth season of Byron Schenkman & Friends! I am very grateful for the joyful enthusiasm which has surrounded this series, from our first concert of Beethoven Piano Quartets three years ago up to the present. Our programs often juxtapose familiar works, such as a beloved Bach concerto or Mozart quartet, with wonderful music we may be hearing for the first time, including works by women such as Fanny Mendelssohn and Elisabeth Jacquet de la Guerre. Each year we reconnect with old friends and cover, back cover & welcome page photos by will austin by photos page & welcome cover back cover, meet some new friends too, both onstage and among the audience. This season I am especially delighted to welcome Margy Special thanks Crosby, our new General Manager. Margy to our series founders, will keep things flowing smoothly throughout Robert DeLine and Carol Salisbury, the season and is already helping to plan and to all our donors, for our fifth season and beyond. -

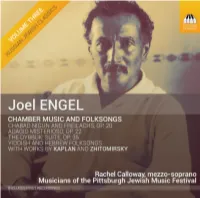

TOCC0343DIGIBKLT.Pdf

JOEL ENGEL Chamber Music and Folksongs I. KAPLAN (18??–19??) 1 Air (Jewish Melody) for violin, harp and harmonium (1912)* 2:59 JOEL ENGEL 2 Adagio Misterioso, Op. 22, for violin, cello, harp and harmonium* 4:57 Three Yiddish Songs for voice, oboe and piano, arr. Cantor Louis Danto 3 Nor nokh dir 2:25 4 Ritshkele 2:49 5 Akh! Nit gut! (Jüdische Volkslieder No.3, 1909) 2:30 The Dybbuk: Suite, Op. 35, for clarinet, strings and percussion 23:24 6 I For What Reason? – From Song of Songs (Mipneh Mah? – M’schir Haschirim) 5:09 7 II Beggars’ Dances (M’choloth Hakabzanim) 6:39 8 III Wedding March (Marsch Chatunah) 2:13 9 IV The Veiling of the Bride (Chipuy Hakalah) 2:34 10 V Hassidic Melody (Nigun Chassidim) 2:27 11 VI From Song of Songs – For What Reason? (reprise) 4:22 12 Hen hu hivtiach li for voice, violin and piano (1923)* 2:50 2 Violinstücke, Op. 20 7:01 13 No. 1 Chabad Nigun, for cello and piano arr. from violin version for cello by Uri Vardi 3:08 14 No. 2 Freylekhs, for violin and piano 3:53 2 Fifty Children’s Songs for voice and piano (1923) 15 No. 9 In der Suke 1:22 I. KAPLAN (18??–19??) 16 No. 8 Shavues 1:17 1 Air (Jewish Melody) for violin, harp and harmonium (1912)* 2:59 17 No. 1 Morgengebet* 1:09 JOEL ENGEL 11 Children’s Songs (Yaldei Sadeh), Op. 36 2 Adagio Misterioso, Op. 22, for violin, cello, harp and harmonium* 4:57 18 No.