Songs from St. Petersburg

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

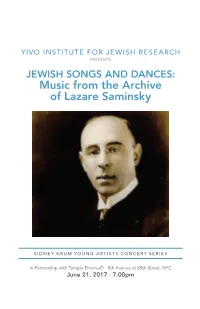

Music from the Archive of Lazare Saminsky

YIVO INSTITUTE FOR JEWISH RESEARCH PRESENTS JEWISH SONGS AND DANCES: Music from the Archive of Lazare Saminsky SIDNEY KRUM YOUNG ARTISTS CONCERT SERIES In Partnership with Temple Emanu-El · 5th Avenue at 65th Street, NYC June 21, 2017 · 7:00pm PROGRAM The Sidney Krum Young Artists Concert Series is made possible by a generous gift from the Estate of Sidney Krum. In partnership with Temple Emanu-El. Saminsky, Hassidic Suite Op. 24 1-3 Saminsky, First Hebrew Song Cycle Op. 12 1-3 Engel, Omrim: Yeshnah erets Achron, 2 Hebrew Pieces Op. 35 No. 2 Saminsky, Second Hebrew Song Cycle Op. 13 1-3 Saminsky, A Kleyne Rapsodi Saminsky, And Rabbi Eliezer Said Engel, Rabbi Levi-Yitzkah’s Kaddish Achron, Sher Op. 42 Saminsky, Lid fun esterke Saminsky, Shir Hashirim Streicher, Shir Hashirim Engel, Freylekhs, Op. 21 Performers: Mo Glazman, Voice Eliza Bagg, Voice Brigid Coleridge, Violin Julian Schwartz, Cello Marika Bournaki, Piano COMPOSER BIOGRAPHIES Born in Vale-Gotzulovo, Ukraine in 1882, LAZARE SAMINSKY was one of the founding members of the Society for Jewish Folk Music in St. Petersburg – a group of composers committed to forging a new national style of Jewish classical music infused with Jewish folk melodies and liturgical music. Saminksy’s teachers at the St. Petersburg conservatory included Rimsky-Korsakov and Liadov. Fascinated with Jewish culture, Saminsky went on trips to Southern Russia and Georgia to gather Jewish folk music and ancient religious chants. In the 1910s Saminsky spent a substantial amount of time travelling giving lectures and conducting concerts. Saminsky’s travels brought him to Turkey, Syria, Palestine, Paris, and England. -

A Hebrew Liederabend an Evening of Hebrew Song Tuesday, June 4, 2019

A Hebrew Liederabend An Evening of Hebrew Song Tuesday, June 4, 2019 ANNE E. LEIBOWITZ MEMORIAL CONCERT Program 6:00pm Pre-Concert Lecture Including music by 7:00pm Concert JOSEPH ACHRON JOEL ENGEL Performed by ALEXANDER KREIN ILANA DAVIDSON PAUL BEN-HAIM RAPHAEL FRIEDER OFER BEN-AMOTS ELIZABETH SHAMMASH and poetry by YEHUDI WYNER and guest artist RONN YEDIDIA SHAUL TCHERNICHOVSKY AVIGDOR HAMEIRI Devised by YEHUDA HALEVI NEIL W. LEVIN LEAH GOLDBERG RACHEL HAYIM NAHMAN BIALIK This event is part of the Smithsonian Year of Music. and others… YIVO INSTITUTE FOR JEWISH RESEARCH in the Center for Jewish History 15 WEST 16TH STREET · NYC PROGRAM INTERMISSION אומרים: ישנה ארץ | THEY SAY THERE IS A LAND נעמי שמר | Music by Naomi Shemer | 1930-2004 שאול טשרניחובסקי | Words by Shaul Tchernichovsky | 1875-1943 כיבוי אורות | LIGHTS OUT נעמי שמר | Music and Words by Naomi Shemer | 1930-2004 אומרים: ישנה ארץ | THEY SAY THERE IS A LAND מנחם ויזנברג | Arranged by Menachem Wiesenberg | 1950- יואל אנגל | Music by Joel Engel | 1868-1927 שאול טשרניחובסקי | Words by Shaul Tchernichovsky | 1875-1943 שיר ליקינתון | THE HYACINTH רבקה גוילי | Melody by Rivka Gwily שני מכתבים | TWO LETTERS לאה גולדברג | Words by Lea Goldberg | 1911-1970 יואל אנגל | Music by Joel Engel | 1868-1927 מנחם ויזנברג | Arranged by Menachem Wiesenberg | 1950- אביגדור המאירי | Words by Avigdor Hameiri | 1890-1970 הנך יפה רעיתי | BEHOLD, THOU ART FAIR גלות | IN EXILE ידידיה אדמון | Music by Yedidiya Admon | 1894-1982 היינריך שליט | Music by Heinrich Schalit | 1886-1976 שיר השירים | Words -

TOCC0479DIGIBKLT.Pdf

SOLOMON ROSOWSKY Chamber Music and Yiddish Songs 1 Rhapsodie: Récitatif et Danse Hassidique for cello and piano (1934) 5:54 2 An der Wiege for violin and piano (1924) 4:21 3 Fantastic Dance, Op. 6, for violin, cello and piano 10:00 Three Yiddish songs for voice and piano 4 Lomir zikh iberbetn (1914) 1:31 5 A viglid, Op. 4, No. 2 5:06 6 Ikh bin a bal-agole (1914) 1:08 [Three Pieces], Op. 8* 14:21 7 No. 1 ‘Chassidic Melody’, for oboe and piano 6:10 8 No. 2 ‘Nigun on a sof’, for fute, oboe/cor anglais, clarinet and two bassoons 3:20 9 No. 3 ‘Moshe der shuster’, for fute/piccolo, oboe, clarinet and two bassoons 4:51 *FIRST RECORDINGS 10 Viglid No. 2 (‘Ale-lule’) for voice and piano (c. 1917) 4:47 Suite from ‘Jacob and Rachel’ for voice, piano four hands, fute and percussion (1927)* 16:11 11 I Entrance of the Slaves 3:03 12 II Rachel’s Appearance and Dance 1:23 13 III Lavan’s Haste 1:01 14 IV Leah’s Lament and the Brothers’ Entertainment 7:23 15 V Dance of Lavan’s Folk 3:21 TT 63:19 2 Sari Gruber, soprano 10 Rachel Calloway, mezzo-soprano 4 – 6 14 Musicians of the Pittsburgh Jewish Music Festival Damian Bursill-Hall, fute and piccolo 8 – 9 Beverly Crawford, fute 12 – 15 Scott Bell, oboe and cor anglais 8 – 9 Rita Mitsel, oboe 7 Ron Samuels, clarinet 8 – 9 Philip Pandolf, bassoon I 8 – 9 James Rodgers, bassoon II 8 – 9 George Willis, percussion 12 – 15 Nurit Pacht, violin 2 3 Aron Zelkowicz, cello 1 3 Luz Manriquez, piano 1 10 – 15 Anastasia Seifetdinova, piano 7 Natasha Snitkovsky, piano 2 – 6 11 – 15 *FIRST RECORDINGS TT 63:19 3 SOLOMON ROSOWSKY, RENAISSANCE MAN OF JEWISH MUSIC by Samuel Zerin Solomon Rosowsky (1878–1962) was born in Riga, the capital of Latvia, to a home bubbling with Jewish and classical music. -

TFG- La Nova Escola Jueva

I Treball Fi de grau La Nova Escola Jueva Una renaixença cultural Estudiant: Isaac Bachs Viñuela Especialitat/ Àmbit/Modalitat: Interpretació CiC- Violí Director/a: Miguel Simarro Grande Curs: 2016-2017 Vistiplau del director/a del Treball EXTRACTE TRILÍNGÜE The present work aims to explain the elements that led to the birth of a jewish cultural renaissance in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, as well as its development and subsequent influence on key composers of western music, such as Shostakovich and Prokofiev. Thereby, this work is widely documented from a printed bibliography of renowned jewish musicologists, such as Israel Adler and Abraham Idelssohn, as well as works made from the point of view of the performer, such as those made by pianists Jascha Nemtsov and Alexander Tentser, among others. Thanks to this work, I have found out that the New Jewish School was a stylistic embryo that later crystallized into the works of Shostakovich and Prokofiev, among others, and that, on the other hand, its members and repertoire have gone through an undeserved oblivion. El presente trabajo quiere explicar los factores que propiciaron el nacimiento de un renacer cultural judío a finales de siglo XIX y principios del XX, así como su desarrollo i la incidencia posterior en los compositores cruciales de la música occidental, como son Shostakovich i Prokofiev. Para ello, este trabajo está documentado ampliamente a partir de bibliografía impresa de musicólogos judíos especializados de gran nombre, como son Israel Adler y Abraham Idelssohn, así como de trabajos hechos desde la perspectiva del intérprete, como son los realizados por los pianistas Jascha Nemtsov y Alexander Tentser, entre otros. -

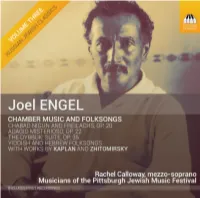

TOCC0343DIGIBKLT.Pdf

JOEL ENGEL Chamber Music and Folksongs I. KAPLAN (18??–19??) 1 Air (Jewish Melody) for violin, harp and harmonium (1912)* 2:59 JOEL ENGEL 2 Adagio Misterioso, Op. 22, for violin, cello, harp and harmonium* 4:57 Three Yiddish Songs for voice, oboe and piano, arr. Cantor Louis Danto 3 Nor nokh dir 2:25 4 Ritshkele 2:49 5 Akh! Nit gut! (Jüdische Volkslieder No.3, 1909) 2:30 The Dybbuk: Suite, Op. 35, for clarinet, strings and percussion 23:24 6 I For What Reason? – From Song of Songs (Mipneh Mah? – M’schir Haschirim) 5:09 7 II Beggars’ Dances (M’choloth Hakabzanim) 6:39 8 III Wedding March (Marsch Chatunah) 2:13 9 IV The Veiling of the Bride (Chipuy Hakalah) 2:34 10 V Hassidic Melody (Nigun Chassidim) 2:27 11 VI From Song of Songs – For What Reason? (reprise) 4:22 12 Hen hu hivtiach li for voice, violin and piano (1923)* 2:50 2 Violinstücke, Op. 20 7:01 13 No. 1 Chabad Nigun, for cello and piano arr. from violin version for cello by Uri Vardi 3:08 14 No. 2 Freylekhs, for violin and piano 3:53 2 Fifty Children’s Songs for voice and piano (1923) 15 No. 9 In der Suke 1:22 I. KAPLAN (18??–19??) 16 No. 8 Shavues 1:17 1 Air (Jewish Melody) for violin, harp and harmonium (1912)* 2:59 17 No. 1 Morgengebet* 1:09 JOEL ENGEL 11 Children’s Songs (Yaldei Sadeh), Op. 36 2 Adagio Misterioso, Op. 22, for violin, cello, harp and harmonium* 4:57 18 No. -

4.3 INSTRUMENTALS by JEWISH ARTISTS Leonard Bernstein Conductor and Pianist in Tutti Barber – Adagio for Strings Gershwin –

4.3 INSTRUMENTALS BY JEWISH ARTISTS Leonard Bernstein Conductor and pianist in Tutti Barber – Adagio for Strings Gershwin – An American in Paris Mahler – Adagietto from Symphony No. 5 Bernstein -- On the Town-Dances Ravel –Concerto in G Halil Duo Aaron Goldman, flute, & Rose Shlyam Grace, piano Achron – Hebrew Lullaby and Dance Ben-Haim – Sephardic Melody Schoenfeld – Ufaratsta Bloch – Suite Modale Lakner - Sonata Vladimir Horowitz Bach/Busoni -- Chorale Prelude Nun komm’der Heiden Heiland Mozart – Piano Sonata in C major Chopin – Mazurka in A minor Chopin – Scherzo no. 1 in B minor Schubert – Impromptu in A flat major Liszt – Consolation no. 3 in D flat major Schumann – Novellette in F major Rachmaninov – Prelude in G sharp minor Scriabin – Etude in C sharp minor Chopin – Polonaise no. 6 in A flat major Moszkowski – Etude in F major Jerusalem Trio Ravel – Piano Trio in A minor Shostakovich – Piano Trio No. 2 in E minor Clarinetist David Krakauer et al Klezmer Concertos & Encores Starer – K’li Zemer Schoenfield – Klezmer Rondos Weinberg – The Maypole & Canzonetta Ellstein – Hassidic Dance Golijov -- Rocketekya Clarinetist David Krakauer with the Kronos Quartet Golijov, The Dreams and Prayers of Isaac the Blind Los Angeles-St. Petersburg Russian Folk Orchestra Russian Strings in Concert Firebird Quartet Magic String Duo The New Israel Woodwind Quintet Mozart – Quintet for Piano, Oboe, Clarinet, Horn & Bassoon in E flat major Hindemith – Kammermusik fur 5 Blaser (Flute, Oboe, Clarinet, Horn & Bassoon) Francaix – Quintet for Flute, Oboe, -

Cambridge Companions Online

Cambridge Companions Online http://universitypublishingonline.org/cambridge/companions/ The Cambridge Companion to Jewish Music Edited by Joshua S. Walden Book DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/CCO9781139151214 Online ISBN: 9781139151214 Hardback ISBN: 9781107023451 Paperback ISBN: 9781107623750 Chapter 11 - From biblical antiquarianism to revolutionary modernism: Jewish a rt music, 1850–1925 pp. 167-186 Chapter DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/CCO9781139151214.012 Cambridge University Press 11 From biblical antiquarianism to revolutionary modernism Jewish art music, 1850–1925 james loeffler Introduction In his memoirs, the Russian Jewish poet and translator Leon Mandelshtam (1819–89) describes an 1840 visit he paid to the legendary Minsk cantor Sender Poliachek (1786–1869). A musical illiterate, Poliachek had won fame for his liturgical compositions that were said to evoke the “soul” of the Jewish past. Mandelshtam himself had fled a small-town life of religious traditionalism for Moscow, where he would become the first Jew to graduate from a Russian university. Yet he felt compelled to stop en route in Minsk to ask the venerable cantor a question: Where did this music of the Jews come from? Was it a product of the East, signifying that the Jews of Russia were descended from the medieval Khazars who had converted to Judaism? Or was it derived from Western Europe, proving that the Jews had migrated to eastern Europe from Spain and Germany, pushed on by the violence of the Crusades? Perhaps, Poliachek replied, since the Jews had lived under both Muslims and Christians, their music was a cultural hybrid: East and West had fused together to produce the distinctive “binational Jewish melody.” The conversation did not end there. -

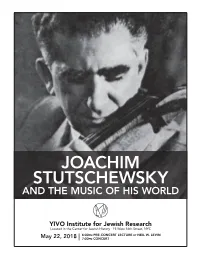

Joachim Stutschewsky and the Music of His World

JOACHIM STUTSCHEWSKY AND THE MUSIC OF HIS WORLD YIVO Institute for Jewish Research Located in the Center for Jewish History · 15 West 16th Street, NYC 6:00PM PRE-CONCERT LECTURE BY NEIL W. LEVIN May 22, 2018 | 7:00PM CONCERT PROGRAM אגדה (Legend (1952 יהויכין סטוצ’בסקי (JOACHIM STUTSCHEWSKY (b. 1891 UKRAINE – d. 1982 ISRAEL for cello and piano סוויטה חסידית (Hasidic Suite (1937 1. Hasidic Dance 2. Meditation 3. Hamavdil לזר סמינסקי (LAZARE SAMINSKY (b. 1882 UKRAINE – D. 1959 USA for cello and piano ֿפריילעכס (Freylekhs: Improvisation (1934 יהויכין סטוצ’בסקי (JOACHIM STUTSCHEWSKY (b. 1891 UKRAINE – d. 1982 ISRAEL for cello and piano מחול זעיר (Jolly Dance (1957 יהויכין סטוצ’בסקי (JOACHIM STUTSCHEWSKY (b. 1891 UKRAINE – d. 1982 ISRAEL for cello and piano ֿפריילעכס (Freylekhs, Op. 21 (1919 יואל אנגל (JOEL ENGEL (b. 1868 RUSSIAN EMPIRE – d. 1927 TEL AVIV for violin, cello, and piano פנטזיה חסידית (Hasidic Fantasy (1954 יהויכין סטוצ’בסקי (JOACHIM STUTSCHEWSKY (b. 1891 UKRAINE – d. 1982 ISRAEL for clarinet, cello, and piano BRIEF INTERMISSION מוסיקה לצ’לו (Music for Violoncello (1977 1. Moderato 2. Rather fast, lively 3. Slow פאול בן-חיים (PAUL BEN-HAIM (b. 1897 GERMANY – d. 1984 ISRAEL for solo cello ניגון והורה (Nigun & Hora* (2018 ניגון: ״יזכור״ The Yizkor Nigun .1 הורה להבה The Flaming Hora .2 עופר בן-אמוץ (OFER BEN-AMOTS (b. 1955 ISRAEL for cello and piano שיר יהודי (Shir Yehudi (1937 יהויכין סטוצ’בסקי (JOACHIM STUTSCHEWSKY (b. 1891 UKRAINE – d. 1982 ISRAEL for cello and piano מוסיקה כליזמרית לחתונה (Klezmer’s Wedding Music (1955 יהויכין סטוצ’בסקי (JOACHIM STUTSCHEWSKY (b. -

A FORGOTTEN LEGACY by Paula Eisenstein Baker, Robert S

LEO ZEITLIN: A FORGOTTEN LEGACY by Paula Eisenstein Baker, Robert S. Nelson and Aron Zelkowicz1 A superbly talented composer and arranger, Leo Zeitlin (1884–1930) was also a violinist, violist, conductor, impresario and teacher. He was an important member of the Society for Jewish Folk Music in St Petersburg, which was the catalyst for a brief but golden age of art-music on Jewish themes drawn from cantillation, liturgical tunes and folksong. The major legacy of the Society was the body of works by its member composers,2 and between 1909 and 1918 it published at least eighty original compositions and arrangements, four of them by Zeitlin (three of them included on this CD: tracks 2, 8 and A). Solomon Rosowsky, a fellow member of the Society, wrote of Zeitlin: His skill at orchestration was the subject of envy among his friends in the field of Jewish music. With this gift he faithfully served the St Petersburg circle of Jewish composers, dressing their solo and chamber works in a shining orchestral garment.3 When he was almost thirteen, Zeitlin left his birthplace of Pinsk (now in Belarus) for Odessa to attend the music school of the local branch of the Imperial Russian Music Society.4 By the time he had completed the academic and music curriculum, someone with his training could easily have begun to play professionally. But there was a compelling reason for any young man of nineteen to continue formal studies: a diploma from either the St Petersburg or Moscow Conservatoire would earn him the title ‘free artist’, which would promote him to the social estate of ‘honoured citizen’, exempting him from the draft and allowing him to travel freely. -

Jüdische Kunstmusik Im 20. Jahrhundert Quellenlage, Entstehungsgeschichte, Stilanalysen

Jüdische Kunstmusik im 20. Jahrhundert Quellenlage, Entstehungsgeschichte, Stilanalysen Herausgegeben von Jascha Nemtsov 2006 Harrassowitz Verlag · Wiesbaden ISSN 16137493 ISBN 344705293-7 ab 1.1.2007: 978-3-447-05293-1 Inhalt Jascha Nemtsov Einführung............................................................................................................ 7 Nachlässe von Komponisten der Neuen Jüdischen Schule in internationalen Archiven Svetlana Martynova The archive of Grigory and Yulian Krejn at the Glinka State Central Museum of Musical Culture ..................................... 15 Olga Brainin Das umfangreiche Archiv von Joachim Stutschewsky in Tel Aviv...................... 37 Eliott Kahn The Solomon Rosowsky Collection and the Solomon Rosowsky Addendum at the Library of the Jewish Theological Seminary .............................................. 47 Gina Genova The estate of Lazare Saminsky at the Milken Archive of American Jewish Music ............................................... 59 Aus der Geschichte der Neuen Jüdischen Schule: Ost und West Neil W. Levin The Russians are coming! – The Russians have stayed! A little known episode in the history of the New Jewish National Music School: the tour of the Palestine Chamber Music Ensemble “Zimro”............................... 73 Jascha Nemtsov Neue jüdische Musik in Polen in den 1920er–30er Jahren .................................. 91 Per Skans Ein Anfang nach dem Ende. Jüdische Kompositionen von Mieczysław Weinberg und Dmitrij Schostakowitsch.......................................... -

Download Liner Notes

Cover Art Music of Dance A MESSAGE FROM THE MILKEN ARCHIVE FOUNDER Dispersed over the centuries to all corners of the earth, the Jewish people absorbed elements of its host cultures while, miraculously, maintaining its own. As many Jews reconnected in America, escaping persecution and seeking to take part in a visionary democratic society, their experiences found voice in their music. The sacred and secular body of work that has developed over the three centuries since Jews first arrived on these shores provides a powerful means of expressing the multilayered saga of American Jewry. While much of this music had become a vital force in American and world culture, even more music of specifically Jewish content had been created, perhaps performed, and then lost to current and future generations. Believing that there was a unique opportunity to rediscover, preserve and transmit the collective memory contained within this music, I founded the Milken Archive of American Jewish Music in 1990. The passionate collaboration of many distinguished artists, ensembles and recording producers over the past fourteen years has created a vast repository of musical resources to educate, entertain and inspire people of all faiths and cultures. The Milken Archive of American Jewish Music is a living project; one that we hope will cultivate and nourish musicians and enthusiasts of this richly varied musical repertoire. Lowell Milken A MESSAGE FROM THE ARTISTIC DIRECTOR The quality, quantity, and amazing diversity of sacred as well as secular music written for or inspired by Jewish life in America is one of the least acknowledged achievements of modern Western culture. -

A Special Kind of Antisemitism”: on Russian Nationalism and Jewish Music James Loeffler

Yuval 9 (2015) © Jewish Music Research Centre, The Hebrew University of Jerusalem “A Special Kind of Antisemitism”: On Russian Nationalism and Jewish Music James Loeffler In 1958, on the fiftieth anniversary of the founding of the Society for Jewish Folk Music, the composer Solomon Rosowsky published a short memoir, in which he recalled a joke from his student days a half century earlier: 1 “Why are there so many Jewish students at the St. Petersburg Conservatory? Because it is the only school in the Russian Empire with a quota for non-Jewish students.”2 Rosowsky’s joke was pure hyperbole. But it stemmed from a strange fact. On the eve of World War I, over 50% of the St. Petersburg Conservatory student body, or roughly 1200 students, were Jewish. This was at a time when Jews formed roughly four percent of the total Russian imperial population and stringent admissions quotas limited the total official Jewish student percentage in other Russian university-level educational institutions to 7.3 percent (about 2500 students). The statistical disparity effectively meant that nearly one in every three Jewish university-level students in the late Russian Empire was a musician at the St. Petersburg Conservatory.3 While the rest of the Russian educational world strenuously denied Jews entry, Russia’s greatest musical academy welcomed them with open arms. There are many concrete historical reasons for this striking trend.4 But in this article I want to discuss not its actual causes but instead the popular perceptions of the time that encircled this curious phenomenon, elevating it from a sociological pattern to a cultural myth.