Anarchists in the Spanish Civil War

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Spanish Anarchists: the Heroic Years, 1868-1936

The Spanish Anarchists THE HEROIC YEARS 1868-1936 the text of this book is printed on 100% recycled paper The Spanish Anarchists THE HEROIC YEARS 1868-1936 s Murray Bookchin HARPER COLOPHON BOOKS Harper & Row, Publishers New York, Hagerstown, San Francisco, London memoria de Russell Blackwell -^i amigo y mi compahero Hafold F. Johnson Library Ceirtef' "ampsliire College Anrteret, Massachusetts 01002 A hardcover edition of this book is published by Rree Life Editions, Inc. It is here reprinted by arrangement. THE SPANISH ANARCHISTS. Copyright © 1977 by Murray Bookchin. AH rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner without written permission except in the case ofbrief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews. For information address ftee Life Editions, Inc., 41 Union Square West, New York, N.Y. 10003. Published simultaneously in Canada by Fitzhenry & Whiteside Limited, Toronto. First HARPER COLOPHON edition published 1978 ISBN: 0-06-090607-3 78 7980 818210 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 21 Contents OTHER BOOKS BY MURRAY BOOKCHIN Introduction ^ Lebensgefahrliche, Lebensmittel (1955) Prologue: Fanelli's Journey ^2 Our Synthetic Environment (1%2) I. The "Idea" and Spain ^7 Crisis in Our Qties (1965) Post-Scarcity Anarchism (1971) BACKGROUND MIKHAIL BAKUNIN 22 The Limits of the Qty (1973) Pour Une Sodete Ecologique (1976) II. The Topography of Revolution 32 III. The Beginning THE INTERNATIONAL IN SPAIN 42 IN PREPARATION THE CONGRESS OF 1870 51 THE LIBERAL FAILURE 60 T'he Ecology of Freedom Urbanization Without Cities IV. The Early Years 67 PROLETARIAN ANARCHISM 67 REBELLION AND REPRESSION 79 V. -

Cuban Antifascism and the Spanish Civil War: Transnational Activism, Networks, and Solidarity in the 1930S

Cuban Antifascism and the Spanish Civil War: Transnational Activism, Networks, and Solidarity in the 1930s Ariel Mae Lambe Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY 2014 © 2014 Ariel Mae Lambe All rights reserved ABSTRACT Cuban Antifascism and the Spanish Civil War: Transnational Activism, Networks, and Solidarity in the 1930s Ariel Mae Lambe This dissertation shows that during the Spanish Civil War (1936–1939) diverse Cubans organized to support the Spanish Second Republic, overcoming differences to coalesce around a movement they defined as antifascism. Hundreds of Cuban volunteers—more than from any other Latin American country—traveled to Spain to fight for the Republic in both the International Brigades and the regular Republican forces, to provide medical care, and to serve in other support roles; children, women, and men back home worked together to raise substantial monetary and material aid for Spanish children during the war; and longstanding groups on the island including black associations, Freemasons, anarchists, and the Communist Party leveraged organizational and publishing resources to raise awareness, garner support, fund, and otherwise assist the cause. The dissertation studies Cuban antifascist individuals, campaigns, organizations, and networks operating transnationally to help the Spanish Republic, contextualizing these efforts in Cuba’s internal struggles of the 1930s. It argues that both transnational solidarity and domestic concerns defined Cuban antifascism. First, Cubans confronting crises of democracy at home and in Spain believed fascism threatened them directly. Citing examples in Ethiopia, China, Europe, and Latin America, Cuban antifascists—like many others—feared a worldwide menace posed by fascism’s spread. -

The Anarchist Collectives Workers’ Self-Management in the Spanish Revolution, 1936–1939

The Anarchist Collectives Workers’ Self-Management in the Spanish Revolution, 1936–1939 Sam Dolgoff (editor) 1974 Contents Preface 7 Acknowledgements 8 Introductory Essay by Murray Bookchin 9 Part One: Background 28 Chapter 1: The Spanish Revolution 30 The Two Revolutions by Sam Dolgoff ....................................... 30 The Bolshevik Revolution vs The Russian Social Revolution . 35 The Trend Towards Workers’ Self-Management by Sam Dolgoff ....................................... 36 Chapter 2: The Libertarian Tradition 41 Introduction ............................................ 41 The Rural Collectivist Tradition by Sam Dolgoff ....................................... 41 The Anarchist Influence by Sam Dolgoff ....................................... 44 The Political and Economic Organization of Society by Isaac Puente ....................................... 46 Chapter 3: Historical Notes 52 The Prologue to Revolution by Sam Dolgoff ....................................... 52 On Anarchist Communism ................................. 55 On Anarcho-Syndicalism .................................. 55 The Counter-Revolution and the Destruction of the Collectives by Sam Dolgoff ....................................... 56 Chapter 4: The Limitations of the Revolution 63 Introduction ............................................ 63 2 The Limitations of the Revolution by Gaston Leval ....................................... 63 Part Two: The Social Revolution 72 Chapter 5: The Economics of Revolution 74 Introduction ........................................... -

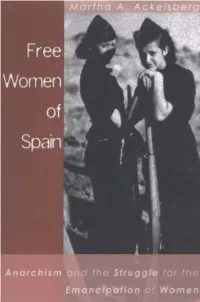

Ackelsberg L

• • I I Free Women of Spain Anarchism and the Struggle for the Emancipation of Women I Martha A. Ackelsberg l I f I I .. AK PRESS Oakland I West Virginia I Edinburgh • Ackelsberg. Martha A. Free Women of Spain: Anarchism and the Struggle for the Emancipation of Women Lihrary of Congress Control Numher 2003113040 ISBN 1-902593-96-0 Published hy AK Press. Reprinted hy Pcrmi"inn of the Indiana University Press Copyright 1991 and 2005 by Martha A. Ackelsherg All rights reserved Printed in Canada AK Press 674-A 23rd Street Oakland, CA 94612-1163 USA (510) 208-1700 www.akpress.org [email protected] AK Press U.K. PO Box 12766 Edinburgh. EH8 9YE Scotland (0131) 555-5165 www.akuk.com [email protected] The addresses above would be delighted to provide you with the latest complete AK catalog, featur ing several thousand books, pamphlets, zines, audio products, videos. and stylish apparel published and distributed bv AK Press. A1tern�tiv�l�! Uil;:1t r\llr "-""'l:-,:,i!'?� f2":' �!:::: :::::;:;.p!.::.;: ..::.:.:..-..!vo' :uh.. ,.",i. IIt;W� and updates, events and secure ordering. Cover design and layout by Nicole Pajor A las compafieras de M ujeres Libres, en solidaridad La lucha continua Puiio ell alto mujeres de Iberia Fists upraised, women of Iheria hacia horiz,ontes prePiados de luz toward horizons pregnant with light por rutas ardientes, on paths afire los pies en fa tierra feet on the ground La frente en La azul. face to the blue sky Atirmondo promesas de vida Affimling the promise of life desafiamos La tradicion we defy tradition modelemos la arcilla caliente we moLd the warm clay de un mundo que nace del doLor. -

Darian Worden Spanish Anarchism 1900-1936 December 15, 2010

Darian Worden Spanish Anarchism 1900-1936 December 15, 2010 (Uploaded to DarianWorden.com January 4, 2011) Anarchism was prevalent in Spain during the period 1900-1936 because of its suitability to Spanish economic, cultural, and political conditions, and because Spanish anarchists were successful at organization and cultural projects. Anarchists were able to create a strong movement that addressed the concerns of the Spanish working classes. During this period the movement was resilient enough to survive repression, flexible enough to be apply itself to different tasks, and ideologically-driven enough to prevent being co-opted by the state. It can be difficult to get a clear picture of events in such a politically-charged history, but a number of secondary sources complement each other to foster better understanding. Gerald Brenan’s The Spanish Labyrinth: An Account of the Social and Political Background of the Civil War is a thorough study of Spanish politics as they developed in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. It contains detailed chapters on anarchism and anarcho-syndicalism, but the book has a broader focus than the anarchist movement. E.J. Hobsbawm’s Primitive Rebels: Studies in Archaic Forms of Social Movement in the 19th and 20th Centuries contains a section on anarchism in the Spanish agrarian region of Andalusia. It is heavily influenced by Brenan’s work. In The Spanish Anarchists: The Heroic Years 1868-1936, Murray Bookchin, writing after Brenan and Hobsbawm, values Brenan’s work and often refers to it, but he criticizes Brenan’s focus on Andalusia and his argument that anarchism had a mystical component. -

Herald of the Future? Emma Goldman, Friedrich Nietzsche and the Anarchist As Superman

The University of Manchester Research Herald of the future? Emma Goldman, Friedrich Nietzsche and the anarchist as superman Document Version Accepted author manuscript Link to publication record in Manchester Research Explorer Citation for published version (APA): Morgan, K. (2009). Herald of the future? Emma Goldman, Friedrich Nietzsche and the anarchist as superman. Anarchist Studies, 17(2), 55-80. Published in: Anarchist Studies Citing this paper Please note that where the full-text provided on Manchester Research Explorer is the Author Accepted Manuscript or Proof version this may differ from the final Published version. If citing, it is advised that you check and use the publisher's definitive version. General rights Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the Research Explorer are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. Takedown policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please refer to the University of Manchester’s Takedown Procedures [http://man.ac.uk/04Y6Bo] or contact [email protected] providing relevant details, so we can investigate your claim. Download date:04. Oct. 2021 Herald of the future? Emma Goldman, Friedrich Nietzsche and the anarchist as superman Kevin Morgan In its heyday around the turn of the twentieth century, Emma Goldman more than anybody personified anarchism for the American public. Journalists described her as anarchy’s ‘red queen’ or ‘high priestess’. At least one anarchist critic was heard to mutter of a ‘cult of personality’.1 Twice, in 1892 and 1901, Goldman was linked in the public mind with the attentats or attempted assassinations that were the movement’s greatest advertisement. -

Sisters in Arms: Women in the Spanish Revolution

SSistersisters inin AArms:rms: WomenWomen inin thethe SpanishSpanish RevolutionRevolution Zabalaza Books “Knowledge is the Key to be Free” Post: Postnet Suite 116, Private Bag X42, Braamfontein, 2017, Johannesburg, South Africa A Collection of Essays from the E-Mail: [email protected] Website: www.zabalaza.net/zababooks Websites of International Anarchism The People Armed - Page 28 Fists upraised, women of Iberia towards horizons pregnant with light on paths afire feet on the ground face to the blue sky. Affirming the promise of life we defy tradition we mold the warm clay of a new world born of pain. Let the past vanish into nothingness! What do we care for yesterday! We want to write anew the word WOMAN. Fists upraised, women of the world towards horizons pregnant with light on paths afire onward, onward toward the light. Mujeres Libres'' Anthem Lucia Sanchez Saornil This pamphlet is made up of texts downloaded from Valencia 1937 the International Pages of the Struggle website and the website of the Workers Solidarity Movement www.struggle.ws They have been edited slightly by the Zabalaza Books editor Women in the Spanish Revolution - Page 27 M Propaganda Consciousness raising and support for these activities was spread by means of literature, including booklets, the "Mujeres Libres" journal, exhibitions, posters, and cross-country tours, especially to rural areas. There are many accounts of urban companeras visiting rural collectives and exchanging ideas, information, etc. (and vice versa). Produced entirely by and for women, the paper Mujeres Libres grew to national circulation and, by all accounts, was popular with both rural and urban work- ing class women. -

Women in the Spanish Revolution - Solidarity

Women in the Spanish revolution - Solidarity Liz Willis writes on the conditions and role of women in and around the Spanish Civil War and revolution of 1936-1939. Solidarity Pamphlet #48 Introduction In a way, it is clearly artificial to try to isolate the role of women in any series of historical events. There are reasons, however, - why the attempt should still be made from time to time; for one thing it can be assumed that when historians write about "people" or "workers" they mean women to anything like the same extent as men. It is only recently that the history of women has begun to be studied with the attention appropriate to women's significance - constituting as we do approximately half of society at all levels. (1) In their magnum opus The Revolution and the Civil War in Spain (Faber & Faber, 1972), Pierre Brow and Emile Témime state that the participation of women in the Spanish Revolution of 1936 was massive and general, and take this as an index of how deep the revolution went. Unfortunately, details of this aspect are scarce in their book elsewhere, but the sources do allow some kind of picture to be pieced together. In the process of examining how women struggled, what they achieved, and how their consciousness developed in a period of intensified social change, we can expect to touch on most facets of what was going on. Any conclusions that emerge should have relevance for libertarians in general as well as for the present-day women's movement. Background Conditions of life for Spanish women prior to 1936 were oppressive and repressive in the extreme. -

Anarchism in Hungary: Theory, History, Legacies

CHSP HUNGARIAN STUDIES SERIES NO. 7 EDITORS Peter Pastor Ivan Sanders A Joint Publication with the Institute of Habsburg History, Budapest Anarchism in Hungary: Theory, History, Legacies András Bozóki and Miklós Sükösd Translated from the Hungarian by Alan Renwick Social Science Monographs, Boulder, Colorado Center for Hungarian Studies and Publications, Inc. Wayne, New Jersey Distributed by Columbia University Press, New York 2005 EAST EUROPEAN MONOGRAPHS NO. DCLXX Originally published as Az anarchizmus elmélete és magyarországi története © 1994 by András Bozóki and Miklós Sükösd © 2005 by András Bozóki and Miklós Sükösd © 2005 by the Center for Hungarian Studies and Publications, Inc. 47 Cecilia Drive, Wayne, New Jersey 07470–4649 E-mail: [email protected] This book is a joint publication with the Institute of Habsburg History, Budapest www.Habsburg.org.hu Library of Congress Control Number 2005930299 ISBN 9780880335683 Printed in the United States of America CONTENTS INTRODUCTION 1 PART ONE: ANARCHIST SOCIAL PHILOSOPHY 7 1. Types of Anarchism: an Analytical Framework 7 1.1. Individualism versus Collectivism 9 1.2. Moral versus Political Ways to Social Revolution 11 1.3. Religion versus Antireligion 12 1.4. Violence versus Nonviolence 13 1.5. Rationalism versus Romanticism 16 2. The Essential Features of Anarchism 19 2.1. Power: Social versus Political Order 19 2.2. From Anthropological Optimism to Revolution 21 2.3. Anarchy 22 2.4. Anarchist Mentality 24 3. Critiques of Anarchism 27 3.1. How Could Institutions of Just Rule Exist? 27 3.2. The Problem of Coercion 28 3.3. An Anarchist Economy? 30 3.4. How to Deal with Antisocial Behavior? 34 3.5. -

Ukraine, L9l8-21 and Spain, 1936-39: a Comparison of Armed Anarchist Struggles in Europe

Bucknell University Bucknell Digital Commons Honors Theses Student Theses Fall 2020 Ukraine, l9l8-21 and Spain, 1936-39: A Comparison of Armed Anarchist Struggles in Europe Daniel A. Collins Bucknell University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.bucknell.edu/honors_theses Part of the European History Commons Recommended Citation Collins, Daniel A., "Ukraine, l9l8-21 and Spain, 1936-39: A Comparison of Armed Anarchist Struggles in Europe" (2020). Honors Theses. 553. https://digitalcommons.bucknell.edu/honors_theses/553 This Honors Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Theses at Bucknell Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of Bucknell Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Ukraine, 1918-21 and Spain, 1936-39: A Comparison of Armed Anarchist Struggles in Europe by Daniel A. Collins An Honors Thesis Submitted to the Honors Council For Honors in History 12/7/2020 Approved by: Adviser:_____________________________ David Del Testa Second Evaluator: _____________________ Mehmet Dosemeci iii Acknowledgements Above all others I want to thank Professor David Del Testa. From my first oddly specific question about the Austro-Hungarians on the Italian front in my first week of undergraduate, to here, three and a half years later, Professor Del Testa has been involved in all of the work I am proud of. From lectures in Coleman Hall to the Somme battlefield, Professor Del Testa has guided me on my journey to explore World War I and the Interwar Period, which rapidly became my topics of choice. -

Revolutionary Action Days of the Exploited Are Cornering the Citadel of Power

For an internationalist bloc of the Special revolutionary forces of the world Issue working class! Page 17 Collective for the Refoundation of the Fourth International International Leninist Trotskyist Fraction June 2020 e-mail: [email protected] • www.flti-ci.org Letter to the JRCL-RMF of Japan United States Minneapolis was the spark... With colossal combats and international solidarity of the workers of the world… Black people, working class and rebellious youth stand up Revolutionary action days of the exploited are cornering the citadel of power Middle East LEBANON: new revolutionary mass upheaval Page 21 IRAN: freedom to the political prisoners in Ayatollahs’ jails! Page 34 The masses of Lebanon clashing against Hezbollah SYRIA: with the infamous regime of Al Assad and Putin, under the US command, the plundering increases, the currency is devaluated and... a generalized starvation takes the people out onto the streets again Page 23 United States Minneapolis was the spark... With colossal combats and international solidarity of the workers of the world... Black people, working class and rebellious youth stand up Revolutionary action days of the exploited are cornering the citadel of power Let the regime fall! Enough of the cynical Biden-Sanders deception of the Democratic Party of the US imperialists butchers! Out with Trump, the leader of the imperialist bandits! Dissolution of the police, the FBI and the CIA! For the defeat of the Pentagon’s fascist officer caste! Black People’s Self-Defense Committees! Workers militia! -

Spain in the Struggle Against Fascism for Almost Three Months the Spanish People Have Been Carrying on a Heroic Struggle Against the Fascist Insurgents

Communist International Nov. (11), 1936, pp. 1418-1438 Spain in the Struggle Against Fascism For almost three months the Spanish people have been carrying on a heroic struggle against the fascist insurgents. Workers from Madrid and Catalonia, peasants from Andalusia and Estremadura, office employees, professors, poets and musicians, are fighting shoulder to shoulder at the front. The whole nation is conducting a life-and-death struggle against a handful of generals, enemies of peace and liberty, who, with the aid of the cutthroat soldiers of the Foreign Legion and duped Moroccan troops, want to restore the rule of the landlords and the church, and to sell the country piecemeal to the German and Italian fascists. This is a struggle of the millions for bread and liberty, for land and work, for the independence of their country. It is a struggle of democracy against the dark forces of reaction and fascism. It is a struggle of the republic against those who are violating the orderly life and peaceful labor of the workers and peasants. It is a struggle against the instigators of war; it is a struggle for peace. The relationship of class forces in Spain is such that fascism has the vast majority of the Spanish people against it, that the people, united in the alliance of the working class, peasants, and working people of the towns, would long since have settled with the revolt, were it not that behind the backs of the Spanish fascists stand the forces of world reaction, and first and foremost, German and Italian fascism.