Bibliographical Essay

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Brief Summer of Anarchy: the Life and Death of Durruti - Hans Magnus Enzensberger

The Brief Summer of Anarchy: The Life and Death of Durruti - Hans Magnus Enzensberger Introduction: Funerals The coffin arrived in Barcelona late at night. It rained all day, and the cars in the funeral cortege were covered with mud. The black and red flag that draped the hearse was also filthy. At the anarchist headquarters, which had been the headquarters of the employers association before the war,1 preparations had already been underway since the previous day. The lobby had been transformed into a funeral chapel. Somehow, as if by magic, everything was finished in time. The decorations were simple, without pomp or artistic flourishes. Red and black tapestries covered the walls, a red and black canopy surmounted the coffin, and there were a few candelabras, and some flowers and wreaths: that was all. Over the side doors, through which the crowd of mourners would have to pass, signs were inscribed, in accordance with Spanish tradition, in bold letters reading: “Durruti bids you to enter”; and “Durruti bids you to leave”. A handful of militiamen guarded the coffin, with their rifles at rest. Then, the men who had accompanied the coffin from Madrid carried it to the anarchist headquarters. No one even thought about the fact that they would have to enlarge the doorway of the building for the coffin to be brought into the lobby, and the coffin-bearers had to squeeze through a narrow side door. It took some effort to clear a path through the crowd that had gathered in front of the building. From the galleries of the lobby, which had not been decorated, a few sightseers watched. -

Workers of the World: International Journal on Strikes and Social Conflicts, Vol

François Guinchard was born in 1986 and studied social sciences at the Université Paul Valéry (Montpellier, France) and at the Université de Franche-Comté (Besançon, France). His master's dissertation was published by the éditions du Temps perdu under the title L'Association internationale des travailleurs avant la guerre civile d'Espagne (1922-1936). Du syndicalisme révolutionnaire à l'anarcho-syndicalisme [The International Workers’ Association before the Spanish civil war (1922-1936). From revolutionary unionism to anarcho-syndicalism]. (Orthez, France, 2012). He is now preparing a doctoral thesis in contemporary history about the International Workers’ Association between 1945 and 1996, directed by Jean Vigreux, within the Centre George Chevrier of the Université de Bourgogne (Dijon, France). His main research theme is syndicalism but he also took part in a study day on the emigration from Haute-Saône department to Mexico in October 2012. Text originally published in Strikes and Social Conflicts International Association. (2014). Workers of the World: International Journal on Strikes and Social Conflicts, Vol. 1 No. 4. distributed by the ACAT: Asociación Continental Americana de los Trabajadores (American Continental Association of Workers) AIL: Associazione internazionale dei lavoratori (IWA) AIT: Association internationale des travailleurs, Asociación Internacional de los Trabajadores (IWA) CFDT: Confédération française démocratique du travail (French Democratic Confederation of Labour) CGT: Confédération générale du travail, Confederación -

Radicalism and the Limits of Reform: the Case of John Reed

DIVISION OF THE HUMANITIES AND SOCIAL SCIENCES CALIFORNIA INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY PASADENA, CALIFORNIA 91125 RADICALISM AND THE LIMITS OF REFORM: THE CASE OF JOHN REED Robert A. Rosenstone To be published in a volume of essays honoring George Mowry HUMANITIES WORKING PAPER 52 September 1980 ABSTRACT Poet, journalist, editorial bo,ard member of the Masses and founding member of the Communist Labor Party, John Reed is a hero in both the worlds of cultural and political radicalism. This paper shows how his development through pre-World War One Bohemia and into left wing politics was part of a larger movement of middle class youngsters who were in that era in reaction against the reform mentality of their parent's generation. Reed and his peers were critical of the following, common reformist views: that economic individualism is the engine of progress; that the ideas and morals of WASP America are superior to those of all other ethnic groups; that the practical constitutes the best approach to social life. By tracing Reed's development on these issues one can see that his generation was critical of a larger cultural view, a system of beliefs common to middle class reformers and conservatives alike. Their revolt was thus primarily cultural, one which tested the psychic boundaries, the definitions of humanity, that reformers shared as part of their class. RADICALISM AND THE LIMITS OF REFORM: THE CASE OF JOHN REED Robert A. Rosenstone In American history the name John Reed is synonymous with radicalism, both cultural and political. Between 1910 and 1917, the first great era of Bohemianism in this country, he was one of the heroes of Greenwich Village, a man equally renowned as satiric poet and tough-minded short story writer; as dashing reporter, contributing editor of the Masses, and co-founder of the Provinceton Players; as lover of attractive women like Mabel Dodge, and friend of the notorious like Bill Haywood, Enma Goldman, Margaret Sanger and Pancho Villa. -

"Red Emma"? Emma Goldman, from Alien Rebel to American Icon Oz

Whatever Happened to "Red Emma"? Emma Goldman, from Alien Rebel to American Icon Oz Frankel The Journal of American History, Vol. 83, No. 3. (Dec., 1996), pp. 903-942. Stable URL: http://links.jstor.org/sici?sici=0021-8723%28199612%2983%3A3%3C903%3AWHT%22EE%3E2.0.CO%3B2-B The Journal of American History is currently published by Organization of American Historians. Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use, available at http://www.jstor.org/about/terms.html. JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use provides, in part, that unless you have obtained prior permission, you may not download an entire issue of a journal or multiple copies of articles, and you may use content in the JSTOR archive only for your personal, non-commercial use. Please contact the publisher regarding any further use of this work. Publisher contact information may be obtained at http://www.jstor.org/journals/oah.html. Each copy of any part of a JSTOR transmission must contain the same copyright notice that appears on the screen or printed page of such transmission. The JSTOR Archive is a trusted digital repository providing for long-term preservation and access to leading academic journals and scholarly literature from around the world. The Archive is supported by libraries, scholarly societies, publishers, and foundations. It is an initiative of JSTOR, a not-for-profit organization with a mission to help the scholarly community take advantage of advances in technology. For more information regarding JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. -

Jews, Masculinity, and Political Violence in Interwar France

Jews, Masculinity, and Political Violence in Interwar France Richard Sonn University of Arkansas On a clear, beautiful day in the center of the city of Paris I performed the first act in front of the entire world. 1 Scholom Schwartzbard, letter from La Santé Prison In this letter to a left-wing Yiddish-language newspaper, Schwartzbard explained why, on 25 May 1926, he killed the former Hetman of the Ukraine, Simon Vasilievich Petliura. From 1919 to 1921, Petliura had led the Ukrainian National Republic, which had briefly been allied with the anti-communist Polish forces until the victorious Red Army pushed both out. Schwartzbard was a Jewish anarchist who blamed Petliura for causing, or at least not hindering, attacks on Ukrainian Jews in 1919 and 1920 that resulted in the deaths of between 50,000 and 150,000 people, including fifteen members of Schwartzbard's own family. He was tried in October 1927, in a highly publicized court case that earned the sobriquet "the trial of the pogroms" (le procès des pogroms). The Petliura assassination and Schwartzbard's trial highlight the massive immigration into France of central and eastern European Jews, the majority of working-class 1 Henry Torrès, Le Procès des pogromes (Paris: Editions de France, 1928), 255-7, trans. and quoted in Felix and Miyoko Imonti, Violent Justice: How Three Assassins Fought to Free Europe's Jews (Amherst, MA: Prometheus, 1994), 87. 392 Jews, Masculinity, and Political Violence 393 background, between 1919 and 1939. The "trial of the pogroms" focused attention on violence against Jews and, in Schwartzbard's case, recourse to violence as resistance. -

ELIZABETH GURLEY FLYNN Labor's Own WILLIAM Z

1111 ~~ I~ I~ II ~~ I~ II ~IIIII ~ Ii II ~III 3 2103 00341 4723 ELIZABETH GURLEY FLYNN Labor's Own WILLIAM Z. FOSTER A Communist's Fifty Yea1·S of ,tV orking-Class Leadership and Struggle - By Elizabeth Gurley Flynn NE'V CENTURY PUBLISIIERS ABOUT THE AUTHOR Elizabeth Gurley Flynn is a member of the National Com mitt~ of the Communist Party; U.S.A., and a veteran leader' of the American labor movement. She participated actively in the powerful struggles for the industrial unionization of the basic industries in the U.S.A. and is known to hundreds of thousands of trade unionists as one of the most tireless and dauntless fighters in the working-class movement. She is the author of numerous pamphlets including The Twelve and You and Woman's Place in the Fight for a Better World; her column, "The Life of the Party," appears each day in the Daily Worker. PubUo-hed by NEW CENTURY PUBLISH ERS, New York 3, N. Y. March, 1949 . ~ 2M. PRINTED IN U .S .A . Labor's Own WILLIAM Z. FOSTER TAUNTON, ENGLAND, ·is famous for Bloody Judge Jeffrey, who hanged 134 people and banished 400 in 1685. Some home sick exiles landed on the barren coast of New England, where a namesake city was born. Taunton, Mass., has a nobler history. In 1776 it was the first place in the country where a revolutionary flag was Bown, "The red flag of Taunton that flies o'er the green," as recorded by a local poet. A century later, in 1881, in this city a child was born to a poor Irish immigrant family named Foster, who were exiles from their impoverished and enslaved homeland to New England. -

Rudolf Rocker Papers 1894-1958 (-1959)1894-1958

Rudolf Rocker Papers 1894-1958 (-1959)1894-1958 International Institute of Social History Cruquiusweg 31 1019 AT Amsterdam The Netherlands hdl:10622/ARCH01194 © IISH Amsterdam 2021 Rudolf Rocker Papers 1894-1958 (-1959)1894-1958 Table of contents Rudolf Rocker Papers...................................................................................................................... 4 Context............................................................................................................................................... 4 Content and Structure........................................................................................................................4 Access and Use.................................................................................................................................5 Allied Materials...................................................................................................................................5 Appendices.........................................................................................................................................6 INVENTAR........................................................................................................................................ 8 PRIVATLEBEN............................................................................................................................ 8 Persönliche und Familiendokumente................................................................................. 8 Rudolf Rocker..........................................................................................................8 -

Together We Will Make a New World Download

This talk, given at ‘Past and Present of Radical Sexual Politics’, the Fifth Meeting of the Seminar ‘Socialism and Sexuality’, Amsterdam October 3-4, 2003, is part of my ongoing research into sexual and political utopianism. Some of the material on pp.1-4 has been re- used and more fully developed in my later article, Speaking Desire: anarchism and free love as utopian performance in fin de siècle Britain, 2009. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License. ‘Together we will make a new world’: Sexual and Political Utopianism by Judy Greenway By reaching for the moon, it is said, we learn to reach. Utopianism, or ‘social dreaming’, is the education of desire for a better world, and therefore a necessary part of any movement for social change.1 In this paper I use examples from my research on anarchism, gender and sexuality in Britain from the 1880s onwards, to discuss changing concepts of free love and the relationship between sexual freedom and social transformation, especially for women. All varieties of anarchism have in common a rejection of the state, its laws and institutions, including marriage. The concept of ‘free love' is not static, however, but historically situated. In the late nineteenth century, hostile commentators linked sexual to political danger. Amidst widespread public discussion of marriage, anarchists had to take a position, and anarchist women placed the debate within a feminist framework. Many saw free love as central to a critique of capitalism and patriarchy, the basis of a wider struggle around such issues as sex education, contraception, and women's economic and social independence. -

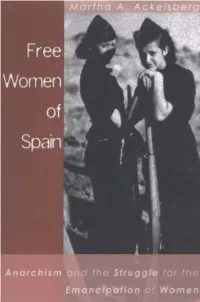

Ackelsberg L

• • I I Free Women of Spain Anarchism and the Struggle for the Emancipation of Women I Martha A. Ackelsberg l I f I I .. AK PRESS Oakland I West Virginia I Edinburgh • Ackelsberg. Martha A. Free Women of Spain: Anarchism and the Struggle for the Emancipation of Women Lihrary of Congress Control Numher 2003113040 ISBN 1-902593-96-0 Published hy AK Press. Reprinted hy Pcrmi"inn of the Indiana University Press Copyright 1991 and 2005 by Martha A. Ackelsherg All rights reserved Printed in Canada AK Press 674-A 23rd Street Oakland, CA 94612-1163 USA (510) 208-1700 www.akpress.org [email protected] AK Press U.K. PO Box 12766 Edinburgh. EH8 9YE Scotland (0131) 555-5165 www.akuk.com [email protected] The addresses above would be delighted to provide you with the latest complete AK catalog, featur ing several thousand books, pamphlets, zines, audio products, videos. and stylish apparel published and distributed bv AK Press. A1tern�tiv�l�! Uil;:1t r\llr "-""'l:-,:,i!'?� f2":' �!:::: :::::;:;.p!.::.;: ..::.:.:..-..!vo' :uh.. ,.",i. IIt;W� and updates, events and secure ordering. Cover design and layout by Nicole Pajor A las compafieras de M ujeres Libres, en solidaridad La lucha continua Puiio ell alto mujeres de Iberia Fists upraised, women of Iheria hacia horiz,ontes prePiados de luz toward horizons pregnant with light por rutas ardientes, on paths afire los pies en fa tierra feet on the ground La frente en La azul. face to the blue sky Atirmondo promesas de vida Affimling the promise of life desafiamos La tradicion we defy tradition modelemos la arcilla caliente we moLd the warm clay de un mundo que nace del doLor. -

Neo-Malthusianism, Anarchism and Resistance: World View and the Limits of Acceptance in Barcelona (1904-1914)

■ Article] ENTREMONS. UPF JOURNAL OF WORLD HISTORY Barcelona ﺍ Universitat Pompeu Fabra Número 4 (desembre 2012) www.entremons.org Neo-Malthusianism, Anarchism and Resistance: World View and the Limits of Acceptance in Barcelona (1904-1914) Daniel PARSONS Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona abstract This paper attempts to identify the barriers to the acceptance of Neo-Malthusian discourse among anarchists and sympathizers in the first years of the 20th century in Barcelona. Neo-Malthusian anarchists advocated the use and promotion of contraceptives and birth control as a way to achieve liberation while subscribing to a Malthusian perspective of nature. The revolutionary discourse was disseminated in Barcelona primarily by the journal Salud y Fuerza and its editor Lluis Bulffi from 1904-1914, at the same time sharing ideological goals with traditional anarchism while clashing with the conception of a beneficent and abundant nature which underpinned traditional anarchist thought. Given the cultural, social and political importance of anarchism to the history of Barcelona in particular and Europe in general, further investigation into Neo-Malthusianism and the response to the discourse is needed in order to understand better the generally accepted world-view among anarchists and how they responded to challenges to this vision. This is a topic not fully addressed by current historiography on Neo- Malthusian anarchism. This article is derived from my Master’s thesis in Contemporary History at the Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona entitled “Neomathusianismo, anarquismo y resistencias: Los límites de su aceptación en Cataluña”, which contains a further exposition of the ideas included herein, as well as a broader perspective on the topic. -

Rancour's Emphasis on the Obviously Dark Corners of Stalin's Mind

Rancour's emphasis on the obviously dark corners of Stalin's mind pre- cludes introduction of some other points to consider: that the vozlzd' was a skilled negotiator during the war, better informed than the keenly intelli- gent Churchill or Roosevelt; that he did sometimes tolerate contradiction and even direct criticism, as shown by Milovan Djilas and David Joravsky, for instance; and that he frequently took a moderate position in debates about key issues in the thirties. Rancour's account stops, save for a few ref- erences to the doctors' plot of 1953, at the end of the war, so that the enticing explanations offered by William McCagg and Werner Hahn of Stalin's conduct in the years remaining to him are not discussed. A more subtle problem is that the great stress on Stalin's personality adopted by so many authors, and taken so far here, can lead to a treatment of a huge country with a vast population merely as a conglomeration of objects to be acted upon. In reality, the influences and pressures on people were often diverse and contradictory, so that choices had to be made. These were simply not under Stalin's control at all times. One intriguing aspect of the book is the suggestion, never made explicit, that Stalin firmly believed in the existence of enemies around him. This is an essential part of the paranoid diagnosis, repeated and refined by Rancour. If Stalin believed in the guilt, in some sense, of Marshal Tukhachevskii et al. (though sometimes Rancour suggests the opposite), then a picture emerges not of a ruthless dictator coldly plotting the exter- mination of actual and potential opposition, but of a fear-ridden, tormented man lashing out in panic against a threat he believed to real and immediate. -

Anarchy! an Anthology of Emma Goldman's Mother Earth

U.S. $22.95 Political Science anarchy ! Anarchy! An Anthology of Emma Goldman’s MOTHER EARTH (1906–1918) is the first An A n t hol o g y collection of work drawn from the pages of the foremost anarchist journal published in America—provocative writings by Goldman, Margaret Sanger, Peter Kropotkin, Alexander Berkman, and dozens of other radical thinkers of the early twentieth cen- tury. For this expanded edition, editor Peter Glassgold contributes a new preface that offers historical grounding to many of today’s political movements, from liber- tarianism on the right to Occupy! actions on the left, as well as adding a substantial section, “The Trial and Conviction of Emma Goldman and Alexander Berkman,” which includes a transcription of their eloquent and moving self-defense prior to their imprisonment and deportation on trumped-up charges of wartime espionage. of E m m A g ol dm A n’s Mot h er ea rt h “An indispensable book . a judicious, lively, and enlightening work.” —Paul Avrich, author of Anarchist Voices “Peter Glassgold has done a great service to the activist spirit by returning to print Mother Earth’s often stirring, always illuminating essays.” —Alix Kates Shulman, author of Memoirs of an Ex-Prom Queen “It is wonderful to have this collection of pieces from the days when anarchism was an ism— and so heady a brew that the government had to resort to illegal repression to squelch it. What’s more, it is still a heady brew.” —Kirkpatrick Sale, author of The Dwellers in the Land “Glassgold opens with an excellent brief history of the publication.