Mourning, Memory and Imagination in the Poetry of José Kozer

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

UC Berkeley UC Berkeley Electronic Theses and Dissertations

UC Berkeley UC Berkeley Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title Sentimental Poetry of the American Civil War Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/4m34b5p3 Author Trapp, Marjorie Jane Publication Date 2010 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California Sentimental Poetry of the American Civil War by Marjorie Jane Trapp A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctorate of Philosophy in English in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Mitchell Breitweiser, Chair Professor Dorri Beam Professor David Henkin Fall 2010 Abstract Sentimental Poetry of the American Civil War by Marjorie Jane Trapp Doctorate of Philosophy in English University of California, Berkeley Professor Mitchell Breitweiser, Chair In her book The Imagined Civil War, Alice Fahs makes a compelling case that Daniel Aaron's seminal claim about the Civil War --- that it was unwritten in every meaningful sense --- misses the point, and, in so doing, looks in the wrong places. Fahs, along with Kathleen Diffley, claims that the American Civil War was very much written, even overwritten, if you look in the many long-overlooked popular periodicals of the war years. I will take Fahs's and Diffley's claims and push them farther, claiming that the Civil War was imaginatively inscribed as a written war in many of its popular poems and songs. This imagined war, or the war as imagined through its popular verse, is a war that is inscribed and circumscribed within images of bounded text and fiction making, and therefore also within issues of authorship, authority, sure knowledge, and the bonds of sentiment. -

Librib 494218.Pdf

OTTOBRE 1997 N. 9 ANNO XIV LIRE 9.500 MENSILE D'INFORMAZIONE - SPED. IN ABB. POST. COMMA 20/b ART. 2, LEGGE 662/96 - ROMA - ISSN 0393 - 3903 Ottobre 1997 In questo numero Giorgio Calcagno, Primo Levi per l'Aned IL LIBRO DEL MESE 28 Carmine Donzelli, De Historia di Hobsbawm 6 Atlante del romanzo europeo 30 Federica Matteoli, La vita di Le Goff di Franco Moretti 31 Norberto Bobbio, Sull'intellettuale di Garin recensito da Mariolina Bertini e Daniele Del Giudice 32 Schede INTERVISTA VIAGGIATORI 33 Giorgio Baratta, Edoardo Sanguineti su Gramsci 8 Piero Boitani, Riletture di Ulisse POLITICA Paola Carmagnani, Viaggio in Oriente di Nerval 9 Franco Marenco, Viaggi in Italia 34 Francesco Ciafaloni, L'autobiografia di Pio Galli 10 Giovanni Cacciavillani, Le Madri di Nerval 36 Cent'anni fa il Settantasette, schede LETTERATURE GIORNALISMO 11 Carlo Lauro, Le Opere di Flaubert 37 Claudio Gorlier, Càndito inviato di guerra Sandro Volpe, Gli anni di Jules e Jim Alberto Papuzzi, Lapidarium di Kapuscinski 12 Marco Buttino, L'autobiografia di Markus Wolf Angela Massenzio, Il mostro di Crane FILOSOFIA 13 Poeti colombiani, fotografe messicane e filosofi spagnoli, schede 38 Roberto Deidier, L'estetica del Romanticismo di Rella Gianni Carchia, Il concilio di Nicea NARRATORI ITALIANI ANTROPOLOGIA 14 Silvio Perrella, Tempo perso di Arpaia 39 Mario Corona, L'immagine dell'uomo di Mosse Cosma Siani, I giubilanti di Cassieri Lidia De Federicis, Percorsi della narrativa italiana: Napoletani SCIENZE 15 Santina Mobiglia, Prigioniere della Torre di Peyrot Biancamaria -

2013-14 Hamilton College Catalogue

2013-14 Hamilton College Catalogue Courses of Instruction Departments and Programs Page 1 of 207 Updated Jul. 31, 2013 Departments and Programs Africana Studies American Studies Anthropology Art Art History Asian Studies Biochemistry/Molecular Biology Biology Chemical Physics Chemistry Cinema and New Media Studies Classics College Courses and Seminars Communication Comparative Literature Computer Science Critical Languages Dance and Movement Studies Digital Arts East Asian Languages and Literatures Economics Education Studies English and Creative Writing English for Speakers of Other Languages Environmental Studies Foreign Languages French Geoarchaeology Geosciences German Studies Government Hispanic Studies History Jurisprudence, Law and Justice Studies Latin American Studies Mathematics Medieval and Renaissance Studies Middle East and Islamic World Studies Music Neuroscience Oral Communication Philosophy Physical Education Physics Psychology Public Policy Religious Studies Russian Studies Sociology Theatre Women's Studies Writing Courses of Instruction Page 2 of 207 Updated Jul. 31, 2013 Courses of Instruction For each course, the numbering indicates its general level and the term in which it is offered. Courses numbered in the 100s, and some in the 200s, are introductory in material and/or approach. Generally courses numbered in the 200s and 300s are intermediate and advanced in approach. Courses numbered in the 400s and 500s are most advanced. Although courses are normally limited to 40 students, some courses have lower enrollment limits due to space constraints (e.g., in laboratories or studios) or to specific pedagogical needs (e.g., special projects, small-group discussions, additional writing assignments). For example, writing-intensive courses are normally limited to 20 students, and seminars are normally limited to 12. -

Easter Traditions Celebrate More Faiths Than Mere Christianity

FFLEETWOODLEETWOOD AREAAREA HIGHHIGH SCHOOSCHOOLL Mar.Mar. 20122012 FieldField HockeyHockey StarStar DelpDelp TakesTakes TalentsTalents toto NorthNorth PhillyPhilly PAGEPAGE 22 PHOTO: TEMPLE UNIVERSITY Volume XX, Issue VIII www.TheTigerTimes.com Fleetwood Easter Traditions Visit The Tiger Times Mobile! NBA Fans Scan this QR Code with your smartphone to Celebrate More Excited For read our newspaper on your mobile device! Faiths than Mere Successful 76ers Season Sports Christianity In the last few years of Philadelphia sports, the Eagles, Flyers, and Phillies are the first Holiday teams one associates with the City of Brotherly Love. But there is another team in Philadelphia many have forgotten about: the 76ers. The days of the Sixers being over- Paganism and fertility are two of the festival that celebrated the arrival of looked are over; the 76ers, with their young up- things most people do not associate with the spring, he could lay eggs that were the col- beat team, have shocked the NBA by starting the “Easter Bunny,” the legendary rabbit who ors of the rainbow to remind him of when season out with a 20-10 record and a 4 game lead brings colorful eggs filled with sweets to he was a bird. in the Atlantic Division. Doug Collins, the second “I am very excited about this season children on Easter Sunday. The bunny was still not the symbol year coach of the 76ers and one-time 76er him- because I am a long time 76ers fan, and it’s good Easter, as most know, is the Chris- of Easter for many years until the Germans self, has led the team in its turn around--a team to see them play well for once," Anthony Par- tian celebration of the resurrection of Jesus began openly celebrating him sometime in that has not won a playoff series zanese, a junior at Fleetwood Area Christ, which begs the question...What does the 1500s. -

Sistema 98 De Comunicação Pres.Prudente

Relatório de Programação Musical Razão Social: Sistema 98 de Comunicação Ltda. CNPJ: 12.573.752/0001-20 Nome Fantasia: 98 FM - PRESIDENTE PRUDENTE SP Dial: Cidade: PRESIDENTE PRUDENTE UF: SP Data Hora Nome da música Nome do intérprete Nome do compositor Gravadora Vivo Mec. 01/01/2021 02:03:50 LASTING LOVER SIGALA FEAT. JAMES ARTHUR X 01/01/2021 02:07:28 KINGS & QUEENS AVA MAX X 01/01/2021 02:10:07 MAGIC KYLIE MINOGUE X 01/01/2021 02:13:35 DYNAMITE BTS X 01/01/2021 02:16:50 GOOD AS HELL LIZZO FEAT. ARIANA GRANDE X 01/01/2021 02:19:26 HAWAI MALUMA FEAT. THE WEEKND X 01/01/2021 02:22:41 SAY SO DOJA CAT X 01/01/2021 02:26:02 VOU DEIXAR SKANK SAMUEL ROSA X CHICO AMARAL 01/01/2021 02:30:17 RAIN ON ME LADY GAGA FEAT. ARIANA GRANDE X 01/01/2021 02:33:17 DESPACITO LUIS FONSI & DADDY YANKEE FEAT. X JUSTIN BIEBER 01/01/2021 02:36:53 SOS AVICII FEAT. ALOE BLACC X 01/01/2021 02:39:28 SUN IS COMING UP DJ MEMÊ FEAT. GAVIN BRADLEY X 01/01/2021 02:43:04 PLEASE ME CARDI B & BRUNO MARS X 01/01/2021 02:46:22 HAVANA CAMILA CABELLO FEAT. YOUNG THUG X 01/01/2021 02:49:51 HYPNOTIZED PURPLE DISCO MACHINE X 01/01/2021 02:52:57 NOTHING BREAKS LIKE A HEART MARK RONSON FEAT. MILEY CYRUS X 01/01/2021 02:56:30 DANCING IN THE MOONLIGHT JUBEL X 01/01/2021 02:59:09 ORPHANS COLDPLAY X 01/01/2021 03:02:25 AMORES E FLORES MELIM X 01/01/2021 03:05:09 ILY (I LOVE YOU BABY) SURF MESA X 01/01/2021 03:08:02 BREAK MY HEART DUA LIPA X 01/01/2021 03:10:55 ON THE FLOOR JENNIFER LOPEZ & PITBULL X 01/01/2021 03:14:45 IN MY MIND DYNORO X 01/01/2021 03:17:39 EVAPORA IZA FEAT. -

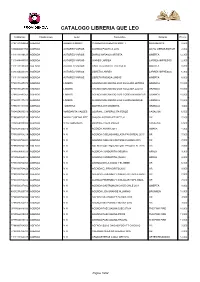

Catalogoqueleopedrodevaldivia40.Pdf

CATALOGO LIBRERIA QUE LEO CodBarras Clasificacion Autor Titulo Libro Editorial Precio 7798141020454 AGENDA ALBERTO MONTT CUADERNO ALBERTO MONTT MONOBLOCK 8,500 1000000001709 AGENDA AUTORES VARIOS AGENDA POLITICA 2012 OCHO LIBROS EDITOR 2,900 1111111199121 AGENDA AUTORES VARIOS DIARIO NARANJA ARTISTA OMERTA 12,300 1111444445551 AGENDA AUTORES VARIOS IMANES LARREA LARREA IMPRESOS 2,900 1111111198988 AGENDA AUTORES VARIOS LIBRETA GRANATE CALCULO OMERTA 8,200 3333344443330 AGENDA AUTORES VARIOS LIBRETA LARREA LARREA IMPRESOS 6,900 1111111198995 AGENDA AUTORES VARIOS LIBRETA ROSADA LINEAS OMERTA 8,500 7798071447376 AGENDA LINIERS AGENDA MACANUDO 2020 ANILLADA LETRAS GRANICA 10,000 7798071447390 AGENDA LINIERS AGENDA MACANUDO 2020 ANILLADA LLUVIA GRANICA 10,000 7798071447352 AGENDA LINIERS AGENDA MACANUDO 2020 COSIDA BANDERAS GRANICA 10,000 7798071447338 AGENDA LINIERS AGENDA MACANUDO 2020 COSIDA BOSQUE GRANICA 10,000 7798071444399 AGENDA . MAITENA MAITENA 007 MAGENTA GRANICA 1,000 7804654930019 AGENDA MARGARITA VALDES JOURNAL, CAPERUCITA FEROZ VASALISA 6,500 7798083702128 AGENDA MARIA EUGENIA PITE CHUICK AGENDA PERPETUA VR 7,200 7804654930002 AGENDA NICO GONZALES JOURNAL PIZZA PALIZA VASALISA 6,500 7804634920016 AGENDA N N AGENDA AMAKA 2011 AMAKA 4,900 7798083704214 AGENDA N N AGENDA COELHO ANILLADA PAVO REAL 2015 VR 7,000 7798083704221 AGENDA N N AGENDA COELHO CANTONE FLORES 2015 VR 7,000 7798083704238 AGENDA N N AGENDA COELHO CANTONE PAVO REAL 2015 VR 7,000 9789568069025 AGENDA N N AGENDA CONDORITO (NEGRA) ORIGO 9,900 9789568069032 AGENDA -

NEMLA 2014.Pdf

Northeast Modern Language Association 45th Annual Convention April 3-6, 2014 HARRISBURG, PENNSYLVANIA Local Host: Susquehanna University Administrative Sponsor: University at Buffalo CONVENTION STAFF Executive Director Fellows Elizabeth Abele SUNY Nassau Community College Chair and Media Assistant Associate Executive Director Caroline Burke Carine Mardorossian Stony Brook University, SUNY University at Buffalo Convention Program Assistant Executive Associate Seth Cosimini Brandi So University at Buffalo Stony Brook University, SUNY Exhibitor Assistant Administrative Assistant Jesse Miller Renata Towne University at Buffalo Chair Coordinator Fellowship and Awards Assistant Kristin LeVeness Veronica Wong SUNY Nassau Community College University at Buffalo Marketing Coordinator NeMLA Italian Studies Fellow Derek McGrath Anna Strowe Stony Brook University, SUNY University of Massachusetts Amherst Local Liaisons Amanda Chase Marketing Assistant Susquehanna University Alison Hedley Sarah-Jane Abate Ryerson University Susquehanna University Professional Development Assistant Convention Associates Indigo Eriksen Rachel Spear Blue Ridge Community College The University of Southern Mississippi Johanna Rossi Special Events Assistant Wagner Pennsylvania State University Francisco Delgado Grace Wetzel Stony Brook University, SUNY St. Joseph’s University Webmaster Travel Awards Assistant Michael Cadwallader Min Young Kim University at Buffalo Web Assistant Workshop Assistant Solon Morse Maria Grewe University of Buffalo Columbia University NeMLA Program -

Guia De Numã©Ros

Inti: Revista de literatura hispánica Number 49 Foro Escritura y Psicoanálisis Article 100 1999 Guia de Numéros Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.providence.edu/inti Citas recomendadas (Primavera-Otoño 1999) "Guia de Numéros," Inti: Revista de literatura hispánica: No. 49, Article 100. Available at: https://digitalcommons.providence.edu/inti/vol1/iss49/100 This Otras Obras is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@Providence. It has been accepted for inclusion in Inti: Revista de literatura hispánica by an authorized editor of DigitalCommons@Providence. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INTI: NUMEROS PUBLICADOS Y LISTA DE PRECIOS PARA SUSCRIPTORES NO. 1 $6.00 Robert G. Mead Jr., Presentación de Inti; ESTUDIOS: Carlos Alberto Pérez, “Canciones y romances (Edad Media-Siglo XVIII)”; Robert G. Mead Jr., “Imágenes y realidades interamericanas”; Nelson R . Orringer, “La espada y el arado: una refutación lírica de Juan Ramón por Blas de Otero”; Luis Alberto Sánchez, “La terca realidad”; CREACIÓN: Saúl Yurkievich, Josefina Romo-Arregui. NO. 2 $6.00 ESTUDIOS: Estelle Irizarri, “El Inquisidor de Ayala y el de Dostoyevsky”; Nelson R. Orringer, “El Góngora rebelde del Don Julián de Goytisolo”; Ronald J. Quirk, “El problema del habla regional en Los Pasos de Ulloa "; Gail Solano, "Las metáforas fisiológicas en Tiempo de silencio de Luis Martín Santos”; CREACIÓN: Flor María Blanco, Pedro Lastra, Antonio Silva Domínguez, Saúl Yurkievich; RESEÑAS: Helen Vendler, "El arco y la lira de Octavio Paz; Robert G. Mead Jr., “El intelectual hispanoamericano y su suerte en Chile”; Francisco Ayala, “Las cartas sobre la mesa”. NO. -

Lecturas Para El Verano Por Autor

LECTURAS PARA EL VERANO POR AUTOR AUTOR TÍTULO SIGNATURA Amadís de Gaula / Garci Rodríguez de Montalvo anotación de Juan Bautista Avalle-Arce A 510/3/25 Cuando se abrió la puerta : cuentos de la nueva mujer (1882-1914) / selección y presentación, Marta Salís traducción, Claudia Conde ... [et al.] A 512/5/26 La dulce mentira de la ficción : ensayos sobre la literatura española actual / Hans Felten, Agustin Valcárcel (eds), en colaboración con David Nelting A 509/7/57 La tragedia de Agamenón, rey de Micenas / Bartolomé Segura Ramos ... [et al.] A 511/6/44 La tragedia de Agamenón, rey de Micenas / Bartolomé Segura Ramos ... [et al.] A 511/6/43 Leer a Hemingway A 509/5/21 Abdolah, Kader El reflejo de las palabras / KaderAbdolah [traducción, Diego Puls Kuipers] A 509/5/31 Agus, Milena Mal de piedras / Milena Agus traducción del italiano de Celia Filipetto. A 512/5/02 Alí, Tariq A la sombra del Granado / Tariq Alí A 508/7/17 Allen, Woody, 1935- Pura anarquía / Woody Allen traducción de Carlos Milla Soler A 508/6/58 Allende, Isabel, 1942- La suma de los días / Isabel Allende A 508/1/14 1 Amat, Núria, 1950- Viajar es muy dificil / Nuria Amat i Noguera prólogo de Ana María Moix A 512/6/24 Amis, Martin La casa de los encuentros / Martin Amis traducción de Jesús Zulaika A 509/6/44 Anasagasti Valderrama, Antonio Arrítmico Amor / Antonio Anasagasti Valderrama A 510/6/41 Antunes, António Lobo Acerca de los pájaros / António Lobo Antunes traducción de Mario Merlino A 509/5/17 El señor Skeffington / Elizabeth von Arnim traducción de Sílvia Pons Arnim, -

Anuario Sobre El Libro Infantil Y Juvenil 2009

122335_001-006_AnuarioInfantilJuvenil_09 27/2/09 11:27 PÆgina 1 gifrs grterstis FUNDACIÓN seromri e 122335_001-006_AnuarioInfantilJuvenil_09 27/2/09 11:27 PÆgina 2 www.grupo-sm.com/anuario.html © Ediciones SM, 2009 Impresores, 2 Urbanización Prado del Espino 28660 Boadilla del Monte (Madrid) www.grupo-sm.com ATENCIÓN AL CLIENTE Tel.: 902 12 13 23 Fax: 902 24 12 22 e-mail: [email protected] ISBN: 978-84-675-3466-5 Depósito legal: Impreso en España / Printed in Spain Gohegraf Industrias Gráficas, SL - 28977 Casarrubuelos (Madrid) Cualquier forma de reproducción, distribución, comunicación pública o transformación de esta obra solo puede ser realizada con la autorización de sus titulares, salvo excepción prevista por la ley. Diríjase a CEDRO (Centro Español de Derechos Reprográficos, www.cedro.org) si necesita fotocopiar o escanear algún fragmento de esta obra. 122335_001-006_AnuarioInfantilJuvenil_09 27/2/09 11:27 PÆgina 3 ÍNDICE Presentación 5 1. Cifras y estadísticas: 7 LA LIJ en 2009 Departamento de Investigación de SM 2. Características y tendencias: 27 AÑO DE FANTASY, EFEMÉRIDES Y REALISMO Victoria Fernández 3. Actividad editorial en catalán: 37 TIEMPO DE BONANZA Te re s a M a ñ à Te r r è 4. Actividad editorial en gallego: 45 PRESENCIA Y TRASCENDENCIA Xosé Antonio Neira Cruz 5. Actividad editorial en euskera: 53 BUENA COSECHA Xabier Etxaniz Erle 6. La vida social de la LIJ: 61 DE CLÁSICOS Y ALLEGADOS, DE HONESTIDAD Y OPORTUNISMO... Sara Moreno Valcárcel 7. Actividad editorial en Brasil: 113 VIGOR Y DIVERSIDAD João Luís Ceccantini 8. Actividad editorial en Chile: 135 ANIMAR A LEER: ¿SALTOS DE ISLOTE EN ISLOTE? María José González C. -

SUMARIO JOSÉ MARÍA MARTÍNEZ, El Público Femenino Del Modernismo

S U M A R I O I. DOSSIERS LITERATURA Y GÉNERO JOSÉ MARÍA MARTÍNEZ, El público femenino del modernismo: de la lectora figurada a la lectora histórica en las prosas de Gutiérrez Nájera ... ... ... ... ... 15 JOSSIANNA ARROYO, Exilio y tránsitos entre la Norzagaray y Christopher Street: acercamientos a una poética del deseo homosexual en Manuel Ramos Otero 31 DENISE GALARZA SEPÚLVEDA, “Las mujeres son las que comúnmente mandan el mundo”: la feminización de lo político en El carnero ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... 55 JORGE LUIS CAMACHO, Los límites de la transgresión: la virilización de la mujer y la feminización del poeta en José Martí ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... 69 MARISELLE MELÉNDEZ, Inconstancia en la mujer: espacio y cuerpo femenino en el Mercurio peruano, 1791-94 ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... 79 LITERATURA ARGENTINA LELIA AREA, Geografías imaginarias: el Facundo y la Campaña en el Ejército Grande de Domingo Faustino Sarmiento ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... 91 PATRICIO RIZZO-VAST, Paisaje e ideología en Campo nuestro de Oliverio Girondo ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... 105 MARGARITA ROJAS y FLORA OVARES, La tenaz memoria de esos hechos; “El perjurio de la nieve” de Adolfo Bioy Casares ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... 121 LAURA DEMARÍA, Rodolfo Walsh, Ricardo Piglia, la tranquera de Macedonio y el difícil oficio de escribir ... ... ... ... ... ... .. -

ECKHART HELLMUTH the Funerals of the Prussian Kings in the Eighteenth Century

ECKHART HELLMUTH The Funerals of the Prussian Kings in the Eighteenth Century in MICHAEL SCHAICH (ed.), Monarchy and Religion: The Transformation of Royal Culture in Eighteenth-Century Europe (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2007) pp. 451–472 ISBN: 978 0 19 921472 3 The following PDF is published under a Creative Commons CC BY-NC-ND licence. Anyone may freely read, download, distribute, and make the work available to the public in printed or electronic form provided that appropriate credit is given. However, no commercial use is allowed and the work may not be altered or transformed, or serve as the basis for a derivative work. The publication rights for this volume have formally reverted from Oxford University Press to the German Historical Institute London. All reasonable effort has been made to contact any further copyright holders in this volume. Any objections to this material being published online under open access should be addressed to the German Historical Institute London. DOI: 16 The Funerals of the Prussian Kings in the Eighteenth Century ECKHART HELLMUTH The court and court ceremonial are highly popular topics for historical research at present. Peter Burke's 1992 study, The Fabrication of Louis XIV, in particular, has been a major factor in ensuring that historians look more carefully at the forms in which kingly power is represented. 1 As a result, they have become much more aware that courts presented themselves in very different ways. Thus, for example, there are considerable differences between the relatively coherent policy of image-creation such as that pursued by Louis XIV(1643-1715) or the Spanish court under Philip IV (1621-65), 2 and the loose programme of representation followed by the Viennese court at the time of Leopold I (1658- 1705), as analysed by Maria Goloubeva.