UC Berkeley UC Berkeley Electronic Theses and Dissertations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Easter Traditions Celebrate More Faiths Than Mere Christianity

FFLEETWOODLEETWOOD AREAAREA HIGHHIGH SCHOOSCHOOLL Mar.Mar. 20122012 FieldField HockeyHockey StarStar DelpDelp TakesTakes TalentsTalents toto NorthNorth PhillyPhilly PAGEPAGE 22 PHOTO: TEMPLE UNIVERSITY Volume XX, Issue VIII www.TheTigerTimes.com Fleetwood Easter Traditions Visit The Tiger Times Mobile! NBA Fans Scan this QR Code with your smartphone to Celebrate More Excited For read our newspaper on your mobile device! Faiths than Mere Successful 76ers Season Sports Christianity In the last few years of Philadelphia sports, the Eagles, Flyers, and Phillies are the first Holiday teams one associates with the City of Brotherly Love. But there is another team in Philadelphia many have forgotten about: the 76ers. The days of the Sixers being over- Paganism and fertility are two of the festival that celebrated the arrival of looked are over; the 76ers, with their young up- things most people do not associate with the spring, he could lay eggs that were the col- beat team, have shocked the NBA by starting the “Easter Bunny,” the legendary rabbit who ors of the rainbow to remind him of when season out with a 20-10 record and a 4 game lead brings colorful eggs filled with sweets to he was a bird. in the Atlantic Division. Doug Collins, the second “I am very excited about this season children on Easter Sunday. The bunny was still not the symbol year coach of the 76ers and one-time 76er him- because I am a long time 76ers fan, and it’s good Easter, as most know, is the Chris- of Easter for many years until the Germans self, has led the team in its turn around--a team to see them play well for once," Anthony Par- tian celebration of the resurrection of Jesus began openly celebrating him sometime in that has not won a playoff series zanese, a junior at Fleetwood Area Christ, which begs the question...What does the 1500s. -

Da Vinci Code Research

The Da Vinci Code Personal Unedited Research By: Josh McDowell © 2006 Overview Josh McDowell’s personal research on The Da Vinci Code was collected in preparation for the development of several equipping resources released in March 2006. This research is available as part of Josh McDowell’s Da Vinci Pastor Resource Kit. The full kit provides you with tools to equip your people to answer the questions raised by The Da Vinci Code book and movie. We trust that these resources will help you prepare your people with a positive readiness so that they might seize this as an opportunity to open up compelling dialogue about the real and relevant Christ. Da Vinci Pastor Resource Kit This kit includes: - 3-Part Sermon Series & Notes - Multi-media Presentation - Video of Josh's 3-Session Seminar on DVD - Sound-bites & Video Clip Library - Josh McDowell's Personal Research & Notes Retail Price: $49.95 The 3-part sermon series includes a sermon outline, discussion points and sample illustrations. Each session includes references to the slide presentation should you choose to include audio-visuals with your sermon series. A library of additional sound-bites and video clips is also included. Josh McDowell's delivery of a 3-session seminar was captured on video and is included in the kit. Josh's personal research and notes are also included. This extensive research is categorized by topic with side-by-side comparison to Da Vinci claims versus historical evidence. For more information and to order Da Vinci resources by Josh McDowell, visit josh.davinciquest.org. http://www.truefoundations.com Page 2 Table of Contents Introduction: The Search for Truth.................................................................................. -

Sistema 98 De Comunicação Pres.Prudente

Relatório de Programação Musical Razão Social: Sistema 98 de Comunicação Ltda. CNPJ: 12.573.752/0001-20 Nome Fantasia: 98 FM - PRESIDENTE PRUDENTE SP Dial: Cidade: PRESIDENTE PRUDENTE UF: SP Data Hora Nome da música Nome do intérprete Nome do compositor Gravadora Vivo Mec. 01/01/2021 02:03:50 LASTING LOVER SIGALA FEAT. JAMES ARTHUR X 01/01/2021 02:07:28 KINGS & QUEENS AVA MAX X 01/01/2021 02:10:07 MAGIC KYLIE MINOGUE X 01/01/2021 02:13:35 DYNAMITE BTS X 01/01/2021 02:16:50 GOOD AS HELL LIZZO FEAT. ARIANA GRANDE X 01/01/2021 02:19:26 HAWAI MALUMA FEAT. THE WEEKND X 01/01/2021 02:22:41 SAY SO DOJA CAT X 01/01/2021 02:26:02 VOU DEIXAR SKANK SAMUEL ROSA X CHICO AMARAL 01/01/2021 02:30:17 RAIN ON ME LADY GAGA FEAT. ARIANA GRANDE X 01/01/2021 02:33:17 DESPACITO LUIS FONSI & DADDY YANKEE FEAT. X JUSTIN BIEBER 01/01/2021 02:36:53 SOS AVICII FEAT. ALOE BLACC X 01/01/2021 02:39:28 SUN IS COMING UP DJ MEMÊ FEAT. GAVIN BRADLEY X 01/01/2021 02:43:04 PLEASE ME CARDI B & BRUNO MARS X 01/01/2021 02:46:22 HAVANA CAMILA CABELLO FEAT. YOUNG THUG X 01/01/2021 02:49:51 HYPNOTIZED PURPLE DISCO MACHINE X 01/01/2021 02:52:57 NOTHING BREAKS LIKE A HEART MARK RONSON FEAT. MILEY CYRUS X 01/01/2021 02:56:30 DANCING IN THE MOONLIGHT JUBEL X 01/01/2021 02:59:09 ORPHANS COLDPLAY X 01/01/2021 03:02:25 AMORES E FLORES MELIM X 01/01/2021 03:05:09 ILY (I LOVE YOU BABY) SURF MESA X 01/01/2021 03:08:02 BREAK MY HEART DUA LIPA X 01/01/2021 03:10:55 ON THE FLOOR JENNIFER LOPEZ & PITBULL X 01/01/2021 03:14:45 IN MY MIND DYNORO X 01/01/2021 03:17:39 EVAPORA IZA FEAT. -

A Comparative Investigation of Survivor Guilt Among Vietnam Veteran Medical Personnel

Loyola University Chicago Loyola eCommons Dissertations Theses and Dissertations 1991 A Comparative Investigation of Survivor Guilt Among Vietnam Veteran Medical Personnel Maurice E. Kaufman Loyola University Chicago Follow this and additional works at: https://ecommons.luc.edu/luc_diss Part of the Education Commons Recommended Citation Kaufman, Maurice E., "A Comparative Investigation of Survivor Guilt Among Vietnam Veteran Medical Personnel" (1991). Dissertations. 3177. https://ecommons.luc.edu/luc_diss/3177 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses and Dissertations at Loyola eCommons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Loyola eCommons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 3.0 License. Copyright © 1991 Maurice E. Kaufman I\ L-U.M.Pl\RAliVE lNVESTlGATIUN OF SURVlVUH GUILT AM.UNG VIETNAM VEfEHAN MEDICAL PERSONNEL by .Maur·lce E. Kautrw:ln A Vls1:;er· tn ti on 0u bmi t ted to the faculty of the Gt adua te ;ic hcml nf Edu cat; ton o.t Loyola lJni ver-s l Ly of Lhi cago J.n Par·tlal Fulf:lil1oe11t ot the RequirP.ruents •• tor toe IJPp;n:>e oJ IJoctrw o1 Educa.ticm May l 9'J l ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I would like to thank Dr. Manuel Silverman tor giving me the opportunity and independence to pursue various ideas, and for valuable discussions throughout my graduate studies. I am obliged to recognize Dr. Ronald Morgan and Dr. Terry Williams for their useful discussions along with their contributions to this project, without which it would not have been completed. -

The War Romance of the Salvation Army

W""\ A <*.. .J II . ,fllk,^^t(, \J\.1«J BY EVANGELINE BOOTH GRACE LIVINGSTON HILL CORNELL UNIVERSITY LIBRARY BEQUEST OF STEWART HENRY BURNHAM 1943 Corneli University Library D 639.S15B72 3 1924 027 890 171 Cornell University Library The original of tliis bool< is in tine Cornell University Library. There are no known copyright restrictions in the United States on the use of the text. http://www.archive.org/details/cu31924027890171 THE WAR ROMANCE OF THE SALVATION ARMY BY EVANGELINE BOOTH AND GRACE LIVINGSTON HILL William Beamwbll Booth general of the salvation army THE WAR ROMANCE OF THE SALVATION ARMY BY EVANGELINE BOOTH COUfAVDEB-IH-CHIEF, THE BALTATI05 ABMT IS AMEBIO^ AND GRACE LIVINGSTON HILL AVTHOB OF "the EafCHANTKD BABM"; "THB BEST MAH"; **U> UICHAXL"; THB BED SICUiAL," ETC. PHILADELPHIA AND LONDON J. B. LIPPINCOTT COMPANY COFTBIGHT, Ipip, BT J. B. LITPINCOTT COUPA19T BUT UP AND pBnrrcD in unitkd btatdb t Evangeline Booth COMMANDER-IN-CHIEF OF THE SALVATION ABMY IN AMEBICA FOREWORD In presenting the narrative of some of the doings of the Salvation Army during the Tvorld's great conflict for liberty, I aan but aaswering the insistent call of a most generous and appreciative public. When moved to activity by the apparent need, there was never a thought that our humble services would awaken the widespread admiration that has developed. In fact, we did not expect anything further than appreciative recog- nition from those immediately benefited, and the knowledge that our people have proved eo useful is an abundant compensation for all toil and sacrifice, for service is our watchword, and there is no reward equal to that of doing the most good to the most people in the most need. -

ECKHART HELLMUTH the Funerals of the Prussian Kings in the Eighteenth Century

ECKHART HELLMUTH The Funerals of the Prussian Kings in the Eighteenth Century in MICHAEL SCHAICH (ed.), Monarchy and Religion: The Transformation of Royal Culture in Eighteenth-Century Europe (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2007) pp. 451–472 ISBN: 978 0 19 921472 3 The following PDF is published under a Creative Commons CC BY-NC-ND licence. Anyone may freely read, download, distribute, and make the work available to the public in printed or electronic form provided that appropriate credit is given. However, no commercial use is allowed and the work may not be altered or transformed, or serve as the basis for a derivative work. The publication rights for this volume have formally reverted from Oxford University Press to the German Historical Institute London. All reasonable effort has been made to contact any further copyright holders in this volume. Any objections to this material being published online under open access should be addressed to the German Historical Institute London. DOI: 16 The Funerals of the Prussian Kings in the Eighteenth Century ECKHART HELLMUTH The court and court ceremonial are highly popular topics for historical research at present. Peter Burke's 1992 study, The Fabrication of Louis XIV, in particular, has been a major factor in ensuring that historians look more carefully at the forms in which kingly power is represented. 1 As a result, they have become much more aware that courts presented themselves in very different ways. Thus, for example, there are considerable differences between the relatively coherent policy of image-creation such as that pursued by Louis XIV(1643-1715) or the Spanish court under Philip IV (1621-65), 2 and the loose programme of representation followed by the Viennese court at the time of Leopold I (1658- 1705), as analysed by Maria Goloubeva. -

African Women's Empowerment: a Study in Amma Darko's Selected

African women’s empowerment : a study in Amma Darko’s selected novels Koumagnon Alfred Djossou Agboadannon To cite this version: Koumagnon Alfred Djossou Agboadannon. African women’s empowerment : a study in Amma Darko’s selected novels. Linguistics. Université du Maine; Université d’Abomey-Calavi (Bénin), 2018. English. NNT : 2018LEMA3008. tel-02049712 HAL Id: tel-02049712 https://tel.archives-ouvertes.fr/tel-02049712 Submitted on 26 Feb 2019 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. THESE DE DOCTORAT DE LE MANS UNIVERSITE ET DE L’UNIVERSITE D’ABOMEY-CALAVI COMUE UNIVERSITE BRETAGNE LOIRE ÉCOLE DOCTORALE N° 595 ÉCOLE DOCTORALE PLURIDISCIPLINAIRE Arts, Lettres, Langues «Espaces, Cultures et Développement» Spécialité : Littérature africaine anglophone Par Koumagnon Alfred DJOSSOU AGBOADANNON AFRICAN WOMEN’S EMPOWERMENT: A STUDY IN AMMA DARKO’S SELECTED NOVELS Thèse présentée et soutenue à l’Université d’Abomey-Calavi, le 17 décembre 2018 Unités de recherche : 3 LAM Le Mans Université et GRAD Université d’Abomey-Calavi Thèse N° : 2018LEMA3008 Rapporteurs avant soutenance : Komla Messan NUBUKPO, Professeur Titulaire / Université de Lomé / TOGO Philip WHYTE, Professeur Titulaire / Université François Rabelais de Tours / FRANCE Laure Clémence CAPO-CHICHI ZANOU, Professeur Titulaire / Université d’Abomey-Calavi/BENIN Composition du Jury : Présidente : Laure Clémence CAPO-CHICHI ZANOU, Professeur Titulaire / Université d’Abomey-Calavi/BENIN Examinateurs : Augustin Y. -

Remembering the Veteran Disability, Trauma, and the American Civil War, 1861-1915

REMEMBERING THE VETERAN DISABILITY, TRAUMA, AND THE AMERICAN CIVIL WAR, 1861-1915 Erin R. Corrales-Diaz A dissertation submitted to the faculty at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Art. Chapel Hill 2016 Approved by: Ross Barrett Bernard L. Herman John P. Bowles John Kasson Eleanor Jones Harvey © 2016 Erin R. Corrales-Diaz ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii ABSTRACT Erin R. Corrales-Diaz: Remembering the Veteran: Disability, Trauma, and the American Civil War, 1861-1915 (Under the direction of Ross Barrett) My dissertation, “Remembering the Veteran: Disability, Trauma, and the American Civil War, 1861-1915,” explores the complex ways that American artists interpreted war-induced disability after the Civil War. Examining pictorial representations of disabled veterans by George Inness, Thomas Nast, William Bell, and other artists, I argue that the veteran’s broken body became a vehicle for exploring the overwhelming sense of loss that Northerners and Southerners experienced in the war's aftermath. Oscillating between aestheticized ideals and the reality of affliction, visual representations of disabled veterans uncover postwar Americans’ deep and otherwise unspoken anxieties about masculinity, identity, and nationhood. This project represents the first major effort to historicize the visual culture of war-related disability and presents a significant deviation from previous Civil War scholarship and its focus on death. In examining these understudied representations of disability and tracing out the ways that they rework and reinforce nineteenth-century constructions of the body, this project models an approach to the analysis of period imaginings of corporeal difference that might in turn shed new light on contemporary artistic responses to physical and psychological injuries resulting from warfare. -

Billboard Magazine

Lamar photographed Dec. 30, 2015, in downtown Los Angeles. GRAMMYPREVIEW2016 KENDRICK’S February 13, 2016 SWEET | billboard.com REVENGE No, Lamar doesn’t care about those past snubs. Because the Compton rapper with 11 nominations knows this is his best work ever: ‘I want to win them all’ ‘IT’S STILL TOO WHITE, TOO MALE AND TOO OLD’ Grammy voters speak out! ‘THE SECRET IS… TALENT’ How Chris Stapleton conquered country WE PROUDLY CONGRATULATE OUR GRAMMY® THE RECORDING ACADEMY® SONG OF THE YEAR BEST DANCE/ELECTRONIC ALBUM LIFETIME ACHIEVEMENT AWARD ED SHEERAN CARIBOU HERBIE HANCOCK “THINKING OUT LOUD” OUR LOVE RECORD OF THE YEAR BEST NEW ARTIST BEST DANCE/ELECTRONIC ALBUM ED SHEERAN COURTNEY BARNETT DISCLOSURE “THINKING OUT LOUD” CARACAL BEST POP SOLO PERFORMANCE RECORD OF THE YEAR ED SHEERAN BEST DANCE/ELECTRONIC ALBUM MARK RONSON* “THINKING OUT LOUD” SKRILLEX & DIPLO “UPTOWN FUNK” SKRILLEX AND DIPLO PRESENT JACK Ü BEST POP SOLO PERFORMANCE ALBUM OF THE YEAR ELLIE GOULDING* BEST DANCE/ELECTRONIC ALBUM ED SHEERAN “LOVE ME LIKE YOU DO” JAMIE XX BEAUTY BEHIND THE MADNESS IN COLOUR BY THE WEEKND BEST POP DUO/GROUP PERFORMANCE (featured artist) MARK RONSON* BEST ROCK PERFORMANCE ALBUM OF THE YEAR “UPTOWN FUNK” ELLE KING “EX’S & OH’S” FLYING LOTUS BEST POP VOCAL ALBUM TO PIMP A BUTTERFLY MARK RONSON* BEST ROCK PERFORMANCE BY KENDRICK LAMAR UPTOWN SPECIAL WOLF ALICE (producer) “MOANING LISA SMILE” BEST DANCE RECORDING ALBUM OF THE YEAR BEST ROCK SONG JACK ANTONOFF ABOVE & BEYOND “WE’RE ALL WE NEED” ELLE KING (OF FUN. AND BLEACHERS) “EX’S & OH’S” -

Prophet Singer: the Voice and Vision of Woody Guthrie Mark Allan Jackson Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 2002 Prophet singer: the voice and vision of Woody Guthrie Mark Allan Jackson Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Jackson, Mark Allan, "Prophet singer: the voice and vision of Woody Guthrie" (2002). LSU Doctoral Dissertations. 135. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations/135 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please [email protected]. PROPHET SINGER: THE VOICE AND VISION OF WOODY GUTHRIE A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in The Department of English By Mark Allan Jackson B.A., Hendrix College, 1988 M.A., University of Arkansas at Fayetteville, 1995 December 2002 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Many people and institutions should be acknowledged for their help in making my dissertation possible. I have to start off by tipping my hat to certain of my friends, people who first asked me interesting questions or spared with me in argument about music. So I salute Casey Whitt, John Snyder, Cody Walker, Derek Van Lynn, Maxine Beach, and Robin Becker. They helped me see the deep places in America’s music, made me think about its beauty and meaning. -

Brian Eno • • • His Music and the Vertical Color of Sound

BRIAN ENO • • • HIS MUSIC AND THE VERTICAL COLOR OF SOUND by Eric Tamm Copyright © 1988 by Eric Tamm DEDICATION This book is dedicated to my parents, Igor Tamm and Olive Pitkin Tamm. In my childhood, my father sang bass and strummed guitar, my mother played piano and violin and sang in choirs. Together they gave me a love and respect for music that will be with me always. i TABLE OF CONTENTS DEDICATION ............................................................................................ i TABLE OF CONTENTS........................................................................... ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ....................................................................... iv CHAPTER ONE: ENO’S WORK IN PERSPECTIVE ............................... 1 CHAPTER TWO: BACKGROUND AND INFLUENCES ........................ 12 CHAPTER THREE: ON OTHER MUSIC: ENO AS CRITIC................... 24 CHAPTER FOUR: THE EAR OF THE NON-MUSICIAN........................ 39 Art School and Experimental Works, Process and Product ................ 39 On Listening........................................................................................ 41 Craft and the Non-Musician ................................................................ 44 CHAPTER FIVE: LISTENERS AND AIMS ............................................ 51 Eno’s Audience................................................................................... 51 Eno’s Artistic Intent ............................................................................. 55 “Generating and Organizing Variety in -

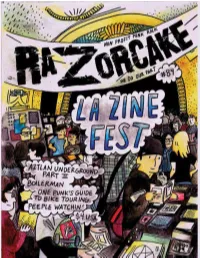

Razorcake Issue #84 As A

RIP THIS PAGE OUT WHO WE ARE... Razorcake exists because of you. Whether you contributed If you wish to donate through the mail, any content that was printed in this issue, placed an ad, or are a reader: without your involvement, this magazine would not exist. We are a please rip this page out and send it to: community that defi es geographical boundaries or easy answers. Much Razorcake/Gorsky Press, Inc. of what you will fi nd here is open to interpretation, and that’s how we PO Box 42129 like it. Los Angeles, CA 90042 In mainstream culture the bottom line is profi t. In DIY punk the NAME: bottom line is a personal decision. We operate in an economy of favors amongst ethical, life-long enthusiasts. And we’re fucking serious about it. Profi tless and proud. ADDRESS: Th ere’s nothing more laughable than the general public’s perception of punk. Endlessly misrepresented and misunderstood. Exploited and patronized. Let the squares worry about “fi tting in.” We know who we are. Within these pages you’ll fi nd unwavering beliefs rooted in a EMAIL: culture that values growth and exploration over tired predictability. Th ere is a rumbling dissonance reverberating within the inner DONATION walls of our collective skull. Th ank you for contributing to it. AMOUNT: Razorcake/Gorsky Press, Inc., a California non-profit corporation, is registered as a charitable organization with the State of California’s COMPUTER STUFF: Secretary of State, and has been granted official tax exempt status (section 501(c)(3) of the Internal Revenue Code) from the United razorcake.org/donate States IRS.