Fabios Paper

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Environmental Project Brief

Public Disclosure Authorized IMPROVED RURAL CONNECTIVITY Public Disclosure Authorized PROJECT (IRCP) REHABILITATION OF PRIMARY FEEDER ROADS IN EASTERN PROVINCE Public Disclosure Authorized ENVIRONMENTAL PROJECT BRIEF September 2020 SUBMITTED BY EASTCONSULT/DASAN CONSULT - JV Public Disclosure Authorized Improved Rural Connectivity Project Environmental Project Brief for the Rehabilitation of Primary Feeder Roads in Eastern Province Improved Rural Connectivity Project (IRCP) Rehabilitation of Primary Feeder Roads in Eastern Province EXECUTIVE SUMMARY The Government of the Republic Zambia (GRZ) is seeking to increase efficiency and effectiveness of the management and maintenance of the of the Primary Feeder Roads (PFR) network. This is further motivated by the recognition that the road network constitutes the single largest asset owned by the Government, and a less than optimal system of the management and maintenance of that asset generally results in huge losses for the national economy. In order to ensure management and maintenance of the PFR, the government is introducing the OPRC concept. The OPRC is a concept is a contracting approach in which the service provider is paid not for ‘inputs’ but rather for the results of the work executed under the contract i.e. the service provider’s performance under the contract. The initial phase of the project, supported by the World Bank will be implementing the Improved Rural Connectivity Project (IRCP) in some selected districts of Central, Eastern, Northern, Luapula, Southern and Muchinga Provinces. The project will be implemented in Eastern Province for a period of five (5) years from 2020 to 2025 using the Output and Performance Road Contract (OPRC) approach. GRZ thus intends to roll out the OPRC on the PFR Network covering a total of 14,333Kms country-wide. -

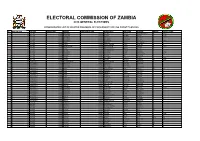

Registered Voters by Gender and Constituency

REGISTERED VOTERS BY GENDER AND CONSTITUENCY % OF % OF SUB % OF PROVINCIAL CONSTITUENCY NAME MALES MALES FEMALES FEMALES TOTAL TOTAL KATUBA 25,040 46.6% 28,746 53.4% 53,786 8.1% KEEMBE 23,580 48.1% 25,453 51.9% 49,033 7.4% CHISAMBA 19,289 47.5% 21,343 52.5% 40,632 6.1% CHITAMBO 11,720 44.1% 14,879 55.9% 26,599 4.0% ITEZH-ITEZHI 18,713 47.2% 20,928 52.8% 39,641 5.9% BWACHA 24,749 48.1% 26,707 51.9% 51,456 7.7% KABWE CENTRAL 31,504 47.4% 34,993 52.6% 66,497 10.0% KAPIRI MPOSHI 41,947 46.7% 47,905 53.3% 89,852 13.5% MKUSHI SOUTH 10,797 47.3% 12,017 52.7% 22,814 3.4% MKUSHI NORTH 26,983 49.5% 27,504 50.5% 54,487 8.2% MUMBWA 23,494 47.9% 25,545 52.1% 49,039 7.4% NANGOMA 12,487 47.4% 13,864 52.6% 26,351 4.0% LUFUBU 5,491 48.1% 5,920 51.9% 11,411 1.7% MUCHINGA 10,072 49.7% 10,200 50.3% 20,272 3.0% SERENJE 14,415 48.5% 15,313 51.5% 29,728 4.5% MWEMBEZHI 16,756 47.9% 18,246 52.1% 35,002 5.3% 317,037 47.6% 349,563 52.4% 666,600 100.0% % OF % OF SUB % OF PROVINCIAL CONSTITUENCY NAME MALES MALES FEMALES FEMALES TOTAL TOTAL CHILILABOMBWE 28,058 51.1% 26,835 48.9% 54,893 5.4% CHINGOLA 34,695 49.7% 35,098 50.3% 69,793 6.8% NCHANGA 23,622 50.0% 23,654 50.0% 47,276 4.6% KALULUSHI 32,683 50.1% 32,614 49.9% 65,297 6.4% CHIMWEMWE 29,370 48.7% 30,953 51.3% 60,323 5.9% KAMFINSA 24,282 51.1% 23,214 48.9% 47,496 4.6% KWACHA 31,637 49.3% 32,508 50.7% 64,145 6.3% NKANA 27,595 51.9% 25,562 48.1% 53,157 5.2% WUSAKILE 23,206 50.5% 22,787 49.5% 45,993 4.5% LUANSHYA 26,658 49.5% 27,225 50.5% 53,883 5.3% ROAN 15,921 50.1% 15,880 49.9% 31,801 3.1% LUFWANYAMA 18,023 50.2% -

Republic of Zambia Living Conditions Monitoring

REPUBLIC OF ZAMBIA LIVING CONDITIONS MONITORING SURVEY III 2002 ENUMERATORS INSTRUCTION MANUAL CENTRAL STATISTICAL OFFICE P.O. BOX 31908 LUSAKA, ZAMBIA. PHONE: 251377/251385/252575/251381/250195/253609/253578/253908 TEL/FAX: 252575/253578/253908/253468 1 Enumerator’s Instructions Manual – LCMS III THE LIVING CONDITIONS MONITORING SURVEY III (2002) ENUMERATOR'S INSTRUCTION MANUAL TABLE OF CONTENTS CHAPTER PAGE CHAPTER I - INTRODUCTION ...................................................................................... 4 CHAPTER II - LISTING PROCEDURE ........................................................................... 9 2.1 Introduction ........................................................................................................... 9 2.2 Identification.......................................................................................................... 9 2.3 Summary of the SEA........................................................................................... 10 2.4 Sampling particulars............................................................................................. 10 2.5 Listing ................................................................................................................... 10 CHAPTER III - ENUMERATION................................................................................... 19 SECTION 1:HOUSEHOLD ROSTER............................................................................. 24 SECTION 2: MARITAL STATUS AND ORPHANHOOD........................................... -

Dissemination Meetings for the Rural Finance

Republic of Zambia Ministry of Finance Investments and Debt Management Department Rural Finance Unit Report on the Rural Finance Policy and Strategy Dissemination Workshop 9th-11th December, 2019 Radisson Blu Hotel, Lusaka TABLE OF CONTENTS 1.0 INTRODUCTION .......................................................................................................... 1 2.0 OBJECTIVE ................................................................................................................... 2 3.0 DISCUSSIONS ............................................................................................................... 2 3.1 Financial Sector Policy Landscape in Zambia ............................................................ 2 3.2 Brief Overview of the Rural Finance Policy and Strategy .......................................... 3 3.2.1 The Role of the Legislature in Rural Finance ...................................................... 4 3.2.2 The Role of Government Line Ministries in Rural Finance ................................ 4 3.2.3 The Role of the Private Sector and Strategic Partners in Rural Finance ............. 4 3.3 The Rural Finance Expansion Programme.................................................................. 5 4.0 SUMMARY AND RECOMMENDATIONS................................................................. 5 APPENDICES ........................................................................................................................... 6 i. Table of Questions Asked .............................................................................................. -

Auditor Generals Main Report for 2018

REPUBLIC OF ZAMBIA REPORT of the AUDITOR GENERAL ON THE ACCOUNTS OF THE REPUBLIC for the Financial Year Ended 31st December 2018 OFFICE OF THE AUDITOR GENERAL VISION: A dynamic audit institution that promotes transparency, accountability and prudent management of public resources. MISSION: To independently and objectively provide quality auditing services in order to assure our stakeholders that public resources are being used for national development and wellbeing of citizens. CORE VALUES: Integrity Professionalism Objectivity Teamwork Confidentiality Excellence Innovation Respect i Contents Preface ....................................................................................................................................... iii Executive Summary ........................................................................................................................................ iv Programme: 2011 Tax Revenue – Zambia Revenue Authority ................................................................ 12 Programme: 2021 Non-Tax Revenue – Road Transport and Safety Agency ........................................... 23 Programmes: 121 Fines - The Judiciary ................................................................................................... 31 Programme: 122 Licences - Ministry of Agriculture ............................................................................. 34 Programmes: 123 Fees - Ministry of Lands and Natural Resources......................................................... 36 Programme: 123 Fees - -

Community-Based Natural Resource Management in Zambia a Review of Institutional Reforms and Lessons Learned from the Field

COMMUNITY-BASED NATURAL RESOURCE MANAGEMENT IN ZAMBIA A REVIEW OF INSTITUTIONAL REFORMS AND LESSONS LEARNED FROM THE FIELD Contract Number: 7200AA18D00003/7200AA18F00015 COR: Sarah Lowery USAID Office of Land and Urban Contractor Name: Tetra Tech Author(s): Anna-Louise Davis, Tom Blomley, Gordon Homer, Matt Sommerville, & Fred Nelson JANUARY 2020 This document was produced for review by the United States Agency for International Development. It was prepared with support from the Integrated Land and Resource Governance Task Order, under the Strengthening Tenure and Resource Rights II (STARR II) IDIQ. It was prepared by MaliasiliCOMMUNITY and Tetra-BASED Tech. NATURAL RESOURCE MANAGEMENT IN ZAMBIA i Cover Photo: South Luangwa National Park. Rena Singer Tetra Tech Contact(s): Megan Huth, Project Manager 159 Bank Street, Suite 300 Burlington, VT 05402 Tel: (802) 495-0282 Fax: (802) 658-4247 Email: [email protected] Suggested Citation: Davis, A-L., Blomley, T., Homer, G., Sommerville, M., & Nelson, F. (2020). Community-based Natural Resource Management in Zambia: A review of institutional reforms and lessons from the field. Washington, DC: Maliasili, the USAID Integrated Land and Resource Governance Task Order under the Strengthening Tenure and Resource Rights II (STARR II) IDIQ, and The Nature Conservancy. COMMUNITY-BASED NATURAL RESOURCE MANAGEMENT IN ZAMBIA ii COMMUNITY-BASED NATURAL RESOURCE MANAGEMENT IN ZAMBIA A REVIEW OF INSTITUTIONAL REFORMS AND LESSONS FROM THE FIELD Submission Date: 29 April 2020 (originally submitted 7 January 2020) Submitted by: Melissa Hall, Deputy Chief of Party Tetra Tech 159 Bank Street, Burlington VT 05401, USA Tel: (802) 495-0282 Fax: (802) 658-4247 Contract Number: 7200AA18D00003/7200AA18F00015 COR Name: Sarah Lowery USAID Office of Land and Urban Contractor Name: Tetra Tech Author(s): Anna-Louise Davis, Tom Blomley, Gordon Homer, Matt Sommerville, & Fred Nelson DISCLAIMER This publication is made possible by the support of the American People through the United States Agency for International Development (USAID). -

LIST of Mps 2(5).Xlsx

ELECTORAL COMMISSION OF ZAMBIA 2016 GENERAL ELECTIONS CONSOLIDATED LIST OF ELECTED MEMBERS OF PARLIAMENT FOR 156 CONSTITUENCIES NO. PROVINCE CODE PROVINCE DISTRICT CODE DISTRICT CONSTITUENCY CODE CONSTITUENCY FIRST NAME SURNAME INITIALS POLITICAL PARTY 1 101 CENTRAL 101001 CHIBOMBO 1010001 KATUBA Patricia MWASHINGWELE C UPND 2 101 CENTRAL 101001 CHIBOMBO 1010002 KEEMBE Princess KASUNE UPND 3 101 CENTRAL 101002 CHISAMBA 1010003 CHISAMBA Chushi KASANDA C UPND 4 101 CENTRAL 101003 CHITAMBO 1010004 CHITAMBO Remember MUTALE C PF 5 101 CENTRAL 101004 ITEZHITEZHI 1010005 ITEZHITEZHI Herbert SHABULA UPND 6 101 CENTRAL 101005 KABWE 1010006 BWACHA Sydney MUSHANGA PF 7 101 CENTRAL 101005 KABWE 1010007 KABWE CENTRAL Tutwa NGULUBE S PF 8 101 CENTRAL 101006 KAPIRI MPOSHI 1010008 KAPIRI MPOSHI Stanley KAKUBO K UPND 9 101 CENTRAL 101007 LUANO 1010009 MKUSHI SOUTH Davies CHISOPA PF 10 101 CENTRAL 101008 MKUSHI 1010010 MKUSHI NORTH Doreen MWAPE PF 11 101 CENTRAL 101009 MUMBWA 1010011 MUMBWA Credo NANJUWA UPND 12 101 CENTRAL 101009 MUMBWA 1010012 NANGOMA Boyd HAMUSONDE IND 13 101 CENTRAL 101010 NGABWE 1010013 LUFUBU Gift CHIYALIKA PF 14 101 CENTRAL 101011 SERENJE 1010014 MUCHINGA Howard KUNDA MMD 15 101 CENTRAL 101011 SERENJE 1010015 SERENJE Maxwell KABANDA M MMD 16 102 COPPERBELT 102001 CHILILABOMBWE 1020016 CHILILABOMBWE Richard MUSUKWA PF 17 102 COPPERBELT 102002 CHINGOLA 1020017 CHINGOLA Matthew NKHUWA PF 18 102 COPPERBELT 102002 CHINGOLA 1020018 NCHANGA Chilombo CHALI PF 19 102 COPPERBELT 102003 KALULUSHI 1020019 KALULUSHI Kampamba CHILUMBA M PF 20 -

C:\Users\Public\Documents\GP JOBS\Gazette\Special Gazette No

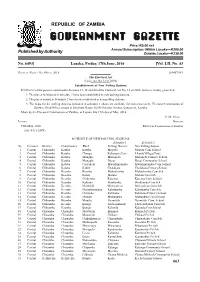

REPUBLIC OF ZAMBIA Price: K5.00 net Annual Subscription: Within Lusaka—K200.00 Published by Authority Outside Lusaka—K230.00 No. 6493] Lusaka, Friday, 17th June, 2016 [Vol. LII, No. 43 GAZETTE NOTICE NO.416OF 2016 [6940718/1 The Electoral Act (Laws, Act No.12 of 2006) Establishment of New Polling Stations INEXERCISEof the powers contained in Sections 37, 38 and 40 of the Electoral Act No. 12 of 2006, notice is hereby given that: 1. The places mentioned in schedule 1 have been established as new polling districts. 2. The places named in Schedule 2 have been established as new polling stations. 3. The maps for the polling districts indicated in schedule 1 above are available for inspection at the Electoral Commission of Zambia, Head Office, situate at Elections House, Haille Selassie Avenue, Longacres, Lusaka. Made by the Electoral Commission of Zambia, at Lusaka this 19th day of May, 2016. P. M. ISAAC, LUSAKA Director 19th May, 2016 Electoral Commission of Zambia (101/5/5/ CONF) SCHEDULE OF NEW POLLING STATIONS Schedule 1 Schedule 2 No. Province District Constituency Ward Polling District New Polling Station 1 Central Chibombo Katuba Katuba Mayota Mayota Com School 2 Central Chibombo Katuba Chungu Kabangwe East Lilanda Village(Tent) 3 Central Chibombo Katuba Mungule Musopelo Musopelo Primary School 4 Central Chibombo Katuba Mungule Duzai Duzai Community School 5 Central Chibombo Katuba Cholokelo Mwashinyambo Mwashinyambo Com School 6 Central Chibombo Katuba Kabile Chalabana Chalabana Primary School 7 Central Chibombo Keembe Keembe Mukachembe -

January-2021-Edition-1

MONTHLY Socialist SOCIALISTPARTY ISSUE 6, DECEMBER 2020/JANUARY 2021 A newsletter published by the Socialist Party, Lusaka, Zambia FREE OF CHARGE The 2021 elections give us a New year, chance to change everything Fred M’membe: Zambia’s and build a future is at stake new hope more just Election will and caring determine society Zambia’s destiny for a generation Socialist staff reporter IF YOU make no other new year’s resolution as we head into 2021, make at least this READY TO TRANSFORM ZAMBIA – Page 6 one: pledge to vote for the So- cialist Party on August 12 and l Meet the latest Socialist Party parliamen- tral), Ambassador Malungisha (Kasempa), me (Kantashi), Mildred Ngambi (Kankoyo), usher in a new era of hope for tary candidates. Womba Nkanza (Zambezi East), Salubeni Kepson Zimba (Kabushi), Humphrey Siame Western Province: Mwisiya Imbula (Senanga Augustine (Mufumbwe), Muchinga Province: (Ndola Central), Bernadette Siabula (Chifu- Zambia through revolution- Central), Edna Biemba (Kaoma Central), Vivian Chunda (Mafinga). Central: Dennis bu), Mercy Bwalya (Bwana Mkubwa), Flannel ary change. Ireen Ilitongo Muhosho (Luena Constitu- Mutumba (Mwembeshi), Misheck Njobo Sichilima (Chingola), Jeff Chabala (Roan), FRED M’MEMBE, Because the Socialist Party ency), Jane Sombo Chingumbe (Mangango), (Nangoma). Copperbelt Province: Nicholas Margaret Sikalonza (Luanshya). Eastern incoming president, Mwenda Kulilisa (Sioma). North Western Mwansa (Kamfinsa), Faston Mwale (Nkana), Province: Doris Mweene (Chipata Central), is the only party that can mean- Province: Salungu Handson (Solwezi Cen- Steven Chewe (Chimwemwe), Mupelwa Sia- Phillip Sakala (Petauke Central). offers #realchange with ingfully tackle hunger, disease, the Socialist Party’s ignorance, and poverty, by pri- policies based on jus- oritising education, health and peasant agriculture. -

Government Gazette

REPUBLIC OF ZAMBIA GOVERNMENT GAZETTE Price: K5.00 net Annual Subscription: Within Lusaka—K250.00 lished byAuthority Outside Lusaka—K300.00 No. 6487] Lusaka, Friday, 27th May, 2016 [Vol. Lil, No. 37 Gazette Notice No. 383 oF 2016 {6940542 Constitution of Zambia (Article 58(4)) (Laws, Act No. 2 of 2016) Establishment of New Constituencies IN exercise of the powers contained in Article 58 of the Constitution of Zambia (Amendment) Act No. 2 of 2016, the following Gazette Notice is hereby made: NOTICE IS HEREBY GIVEN to the general public that pursuant to the increase in the number of constituencies in the Constitution of Zambia(Amendment) Act No. 2 of 2016 from 150 to 156, the Electoral Commission ofZambia conducted delimitation and created six new constituencies indicated in Schedule | hereto. NOTICE IS FURTHER GIVEN to the general public that during the 2016 Delimitation, the Electoral Commission of Zambia renamed the constituencies indicated in Schedule 2 and renumbered the constituencies specified in Schedule 4. The narrative descriptions of the constituencies referred to in Schedule | are outlined in Schedule 3. The new, renamed and renumbered constituencies shali only take effect after the next dissolution of Parliament. The copies of the maps of the new constituencies are available for inspection by membersof the public at the Electoral Commission of Zambia Head Office situated at Elections House, Haile Selassie Avenue, Longacres, Lusaka and at the respective District Councils. Issued by the Electoral Commission of Zambia, at Lusaka this 5th day of May, 2016. P. M. Isaac, Lusaka Director, Sth May, 2616 Electoral Commission ofZambia [101/5/5/ Cone.] SCHEDULE| New ConstITUENCIES No. -

GOUERNMENT GAZETTE Price: K10.00 Net* Annual Subscription: Within Lusaka—K300.00 Published by Authority Outside Lusaka—K350.00

REPUBLIC OF ZAMBIA GOUERNMENT GAZETTE Price: K10.00 net* Annual Subscription: Within Lusaka—K300.00 Published by Authority Outside Lusaka—K350.00 No. 6899] Lusaka, Friday, 21st August, 2020 [Vol. LVI, No. 68 TABLE OF CONTENTS Gazette Notice No. 770 of 2020 [9436495 Gazette Notices No. Page The Bank of Zambia Act Bank of Zambia Act—Assets and Liabilities of Bank (Cap 360 of the Lav/s of Zambia) of Zambia 770 707 Lands and Deeds Registry Act—Establishment of Assets and Liabilities of Bank of Zambia District Registry of Deed Notice, 2020 771 708 In terms of Section 28 of the Bank of Zambia Act, the statement Companies Act: of assets and liabilities of the Bank of Zambia as itSlst July,2020 Notice Under Section 318 772 708 is published for general information in the Schedule hereto. Notice Under Section 318 773 708 Notice Under Section 318 774 708 Lusaka R. C. Mhango, Notice Under Section 318 775 708 31 st July, 2020 Deputy Governor- Administration Notice Under Section 3I8 776 708 Notice Under Section 318 ni 708 Notice Under Section 318 778 708 SCHEDULE Noti ce Under Sec lion 318 779 709 Assets Amount Notice i Jnder Section 318 780 709 IK'000) Notice Under Section 318 781 709 Notice Under Section 318 782 709 IMF Funds Recoverable from Notice Under Section 318 783 709 Government 6,411,636 Notice Under Section 318 784 709 Notice Under Section 318 785 709 Advances to closed Commercial Banks 99,669 Notice Under Section 318 786 709 Advances to Commercial Banks 2,344,593 Marriage Act: Targeted Medium -Term Refinancing Facility 1,093,092 Appointment -

CHAPTER ONE BACKGROUND 1.0 Introduction in Most Democratic Set Ups, Parliaments Are Considered to Be the Central Institutions O

CHAPTER ONE BACKGROUND 1.0 Introduction In most democratic set ups, Parliaments are considered to be the central institutions of democracy. In the Guide on Parliamentary Democracy, the Inter-Parliamentary Union (IPU) describes Parliament as an elected body that represents society in all its diversity. Parliament not only represents citizens as individuals, through the presence of political parties, it also represents them collectively in the pursuit of development and democracy (Revised report on the review of the Parliamentary Reform Programme Capacity Building Component, 2012). In the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) 2012, Global Parliamentary Report, Parliament is considered as the link between the concerns of the people and those that govern. It is said that public pressure on parliaments is greater than ever before. The growth in size of government has increased the responsibilities of parliaments to scrutinize and call to account. The development of communication technology and saturation media coverage of politics has increased the visibility of parliaments and politicians (UNDP and Inter-Parliamentary Union Global Parliamentary Report-the changing nature of parliamentary representation, 2012). The challenge facing parliaments in all parts of the world is one of continual evolution, ensuring that they respond strategically and effectively to changing public demands for representation. Parliamentary reforms are one way that parliaments have adopted to engage in the process of continual improvement (Revised report on the review of the Parliamentary Reform Programme Capacity Building Component, 2012). In Zambia parliamentary reforms have been ongoing since the early 1990s. With the re-introduction of multi party democracy in 1991, and as a way of enhancing democratic governance, the National Assembly of Zambia saw it prudent to realign the functions of Parliament with the demands of plural politics (Report of the Parliamentary Reforms Committee on Reforms in the Zambian Parliament, 2000).