A Tail-Mounted Radio Transmitter for Eastern Bluebirds

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

History of Radio Broadcasting in Montana

University of Montana ScholarWorks at University of Montana Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers Graduate School 1963 History of radio broadcasting in Montana Ron P. Richards The University of Montana Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Richards, Ron P., "History of radio broadcasting in Montana" (1963). Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers. 5869. https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd/5869 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at ScholarWorks at University of Montana. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at University of Montana. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE HISTORY OF RADIO BROADCASTING IN MONTANA ty RON P. RICHARDS B. A. in Journalism Montana State University, 1959 Presented in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Journalism MONTANA STATE UNIVERSITY 1963 Approved by: Chairman, Board of Examiners Dean, Graduate School Date Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. UMI Number; EP36670 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. UMT Oiuartation PVUithing UMI EP36670 Published by ProQuest LLC (2013). -

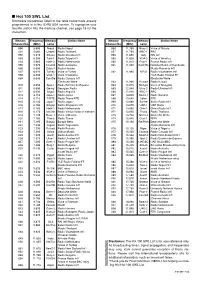

Hot 100 SWL List Shortwave Frequencies Listed in the Table Below Have Already Programmed in to the IC-R5 USA Version

I Hot 100 SWL List Shortwave frequencies listed in the table below have already programmed in to the IC-R5 USA version. To reprogram your favorite station into the memory channel, see page 16 for the instruction. Memory Frequency Memory Station Name Memory Frequency Memory Station Name Channel No. (MHz) name Channel No. (MHz) name 000 5.005 Nepal Radio Nepal 056 11.750 Russ-2 Voice of Russia 001 5.060 Uzbeki Radio Tashkent 057 11.765 BBC-1 BBC 002 5.915 Slovak Radio Slovakia Int’l 058 11.800 Italy RAI Int’l 003 5.950 Taiw-1 Radio Taipei Int’l 059 11.825 VOA-3 Voice of America 004 5.965 Neth-3 Radio Netherlands 060 11.910 Fran-1 France Radio Int’l 005 5.975 Columb Radio Autentica 061 11.940 Cam/Ro National Radio of Cambodia 006 6.000 Cuba-1 Radio Havana /Radio Romania Int’l 007 6.020 Turkey Voice of Turkey 062 11.985 B/F/G Radio Vlaanderen Int’l 008 6.035 VOA-1 Voice of America /YLE Radio Finland FF 009 6.040 Can/Ge Radio Canada Int’l /Deutsche Welle /Deutsche Welle 063 11.990 Kuwait Radio Kuwait 010 6.055 Spai-1 Radio Exterior de Espana 064 12.015 Mongol Voice of Mongolia 011 6.080 Georgi Georgian Radio 065 12.040 Ukra-2 Radio Ukraine Int’l 012 6.090 Anguil Radio Anguilla 066 12.095 BBC-2 BBC 013 6.110 Japa-1 Radio Japan 067 13.625 Swed-1 Radio Sweden 014 6.115 Ti/RTE Radio Tirana/RTE 068 13.640 Irelan RTE 015 6.145 Japa-2 Radio Japan 069 13.660 Switze Swiss Radio Int’l 016 6.150 Singap Radio Singapore Int’l 070 13.675 UAE-1 UAE Radio 017 6.165 Neth-1 Radio Netherlands 071 13.680 Chin-1 China Radio Int’l 018 6.175 Ma/Vie Radio Vilnius/Voice -

Radio Broadcasting

Programs of Study Leading to an Associate Degree or R-TV 15 Broadcast Law and Business Practices 3.0 R-TV 96C Campus Radio Station Lab: 1.0 of Radiologic Technology. This is a licensed profession, CHLD 10H Child Growth 3.0 R-TV 96A Campus Radio Station Lab: Studio 1.0 Hosting and Management Skills and a valid Social Security number is required to obtain and Lifespan Development - Honors Procedures and Equipment Operations R-TV 97A Radio/Entertainment Industry 1.0 state certification and national licensure. or R-TV 96B Campus Radio Station Lab: Disc 1.0 Seminar Required Courses: PSYC 14 Developmental Psychology 3.0 Jockey & News Anchor/Reporter Skills R-TV 97B Radio/Entertainment Industry 1.0 RAD 1A Clinical Experience 1A 5.0 and R-TV 96C Campus Radio Station Lab: Hosting 1.0 Work Experience RAD 1B Clinical Experience 1B 3.0 PSYC 1A Introduction to Psychology 3.0 and Management Skills Plus 6 Units from the following courses (6 Units) RAD 2A Clinical Experience 2A 5.0 or R-TV 97A Radio/Entertainment Industry Seminar 1.0 R-TV 03 Sportscasting and Reporting 1.5 RAD 2B Clinical Experience 2B 3.0 PSYC 1AH Introduction to Psychology - Honors 3.0 R-TV 97B Radio/Entertainment Industry 1.0 R-TV 04 Broadcast News Field Reporting 3.0 RAD 3A Clinical Experience 3A 7.5 and Work Experience R-TV 06 Broadcast Traffic Reporting 1.5 RAD 3B Clinical Experience 3B 3.0 SPCH 1A Public Speaking 4.0 Plus 6 Units from the Following Courses: 6 Units: R-TV 09 Broadcast Sales and Promotion 3.0 RAD 3C Clinical Experience 3C 7.5 or R-TV 05 Radio-TV Newswriting 3.0 -

A Guide for Radio Operators BROCHURE RADIO TRANSM ANG 3/27/97 8:47 PM Page 2

BROCHURE RADIO TRANSM ANG 3/27/97 8:47 PM Page 17 A Guide for Radio Operators BROCHURE RADIO TRANSM ANG 3/27/97 8:47 PM Page 2 Aussi disponible en français. 32-EN-95539W-01 © Minister of Public Works and Government Services Canada 1996 BROCHURE RADIO TRANSM ANG 3/27/97 8:47 PM Page 3 CUTTING THROUGH... INTERFERENCE FROM RADIO TRANSMITTERS A Guide for Radio Operators This brochure is primarily for amateur and General Radio Service (GRS, commonly known as CB) radio operators. It provides basic information to help you install and maintain your station so you get the best performance and the most enjoyment from it. You will learn how to identify the causes of radio interference in nearby electronic equipment, and how to fix the problem. What type of equipment can be affected by radio interference? Both radio and non-radio devices can be adversely affected by radio signals. Radio devices include AM and FM radios, televisions, cordless telephones and wireless intercoms. Non-radio electronic equipment includes stereo audio systems, wired telephones and regular wired intercoms. All of this equipment can be disturbed by radio signals. What can cause radio interference? Interference usually occurs when radio transmitters and electronic equipment are operated within close range of each other. Interference is caused by: ■ incorrectly installed radio transmitting equipment; ■ an intense radio signal from a nearby transmitter; ■ unwanted signals (called spurious radiation) generated by the transmitting equipment; and ■ not enough shielding or filtering in the electronic equipment to prevent it from picking up unwanted signals. What can you do? 1. -

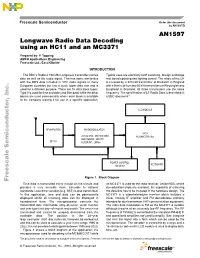

AN1597 Longwave Radio Data Decoding Using an HC11 and an MC3371

Freescale Semiconductor, Inc... microprocessor used for decoding is the MC68HC(7)11 while microprocessor usedfordecodingisthe MC68HC(7)11 2023. and 1995 between distinguish Itisnotpossible to 2022. and thiscanbeusedtocalculate ayearintherange1995to beworked out cyclecan,however, leap–year/year–start–day data.Thepositioninthe28–year available andcannotbeuniquelydeterminedfromthe transmitted and yeartype)intoday–of–monthmonth.Theisnot dateinformation(day–of–week,weeknumber transmitted the form.Themicroprocessorconverts hexadecimal displayed whilst allincomingdatacanbedisplayedin In thisapplication,timeanddatecanbepermanently standards. Localtimevariation(e.g.BST)isalsotransmitted. provides averyaccurateclock,traceabletonational Freescale AMCU ApplicationsEngineering Topping Prepared by:P. This documentcontains informationonaproductunder development. This to thecompanyleasingitforuseinaspecificapplication. available blocks areusedcommerciallywhereeachblockis other 0isusedfortimeanddate(andfillerdata)whilethe Type purpose.There are16datablocktypes. used foradifferent countriesbuthasamuchlowerdatarateandis European with theRDSdataincludedinVHFradiosignalsmany aswelltheaudiosignal.Thishassomesimilarities data using an HC11 and Longwave an Radio MC3371 Data Decoding Figure 1showsablock diagramoftheapplication; Figure data is transmitted every minuteontheand Time The BBC’s Radio4198kHzLongwave transmittercarries The BBC’s Ltd.,EastKilbride RF AMPLIFIERDEMODULATOR FM BF199 FILTER/INT.: LM358 FILTER/INT.: AMP/DEMOD.: MC3371 LOCAL OSC.:MC74HC4060 -

Department of Radio-TV-Broadcasting Longwith Radio, Television and Film Building (LRTF)

Department of Radio-TV-Broadcasting Longwith Radio, Television and Film Building (LRTF) Rules and Regulations for the Use of LRTF ROOM 101 – Lecture/Presentation User Responsibilities • It is the responsibility of the User to maintain adequate controls over all students present so that rules for safe use of the Lecture/Presentation room are followed. • It is the responsibility of the User to insure that only students who are members of the class/event be allowed in the room at the time of its use (excluding RTVF faculty or staff members). • Absolutely no food or drinK is allowed in the room. It is the responsibility of the User to enforce the policy of No Food or Drink in the room during the event. If this rule is violated, it will be the responsibility of the User to see that the room is properly cleaned. • At the beginning of all events taking place in LRTF Room 101, Users should announce the policy that no food or drink is allowed in the room. • At the beginning of all events, Users should announce that the room is monitored through audio/video surveillance equipment. • Absolutely no food or drinK is allowed anywhere in the Longwith Radio, Television and Film building, except the Student Lounge. • Do not rewire, unplug or move any equipment, furniture or other technology. • The use of the Lecture/Presentation Room DOES NOT includes the use of the Student Lounge Area. Room Reservation • You must email Judy Kabo, Academic Unit Assistant in the Radio-TV-Broadcasting Department, the form below. My email is [email protected]. -

A Short History of Radio

Winter 2003-2004 AA ShortShort HistoryHistory ofof RadioRadio With an Inside Focus on Mobile Radio PIONEERS OF RADIO If success has many fathers, then radio • Edwin Armstrong—this WWI Army officer, Columbia is one of the world’s greatest University engineering professor, and creator of FM radio successes. Perhaps one simple way to sort out this invented the regenerative circuit, the first amplifying re- multiple parentage is to place those who have been ceiver and reliable continuous-wave transmitter; and the given credit for “fathering” superheterodyne circuit, a means of receiving, converting radio into groups. and amplifying weak, high-frequency electromagnetic waves. His inventions are considered by many to provide the foundation for cellular The Scientists: phones. • Henirich Hertz—this Clockwise from German physicist, who died of blood poisoning at bottom-Ernst age 37, was the first to Alexanderson prove that you could (1878-1975), transmit and receive Reginald Fessin- electric waves wirelessly. den (1866-1932), Although Hertz originally Heinrich Hertz thought his work had no (1857-1894), practical use, today it is Edwin Armstrong recognized as the fundamental (1890-1954), Lee building block of radio and every DeForest (1873- frequency measurement is named 1961), and Nikola after him (the Hertz). Tesla (1856-1943). • Nikola Tesla—was a Serbian- Center color American inventor who discovered photo is Gug- the basis for most alternating-current lielmo Marconi machinery. In 1884, a year after (1874-1937). coming to the United States he sold The Businessmen: the patent rights for his system of alternating- current dynamos, transformers, and motors to George • Guglielmo Marconi—this Italian crea- Westinghouse. -

Saleh Faruque Radio Frequency Modulation Made Easy

SPRINGER BRIEFS IN ELECTRICAL AND COMPUTER ENGINEERING Saleh Faruque Radio Frequency Modulation Made Easy 123 SpringerBriefs in Electrical and Computer Engineering More information about this series at http://www.springer.com/series/10059 Saleh Faruque Radio Frequency Modulation Made Easy 123 Saleh Faruque Department of Electrical Engineering University of North Dakota Grand Forks, ND USA ISSN 2191-8112 ISSN 2191-8120 (electronic) SpringerBriefs in Electrical and Computer Engineering ISBN 978-3-319-41200-9 ISBN 978-3-319-41202-3 (eBook) DOI 10.1007/978-3-319-41202-3 Library of Congress Control Number: 2016945147 © The Author(s) 2017 This work is subject to copyright. All rights are reserved by the Publisher, whether the whole or part of the material is concerned, specifically the rights of translation, reprinting, reuse of illustrations, recitation, broadcasting, reproduction on microfilms or in any other physical way, and transmission or information storage and retrieval, electronic adaptation, computer software, or by similar or dissimilar methodology now known or hereafter developed. The use of general descriptive names, registered names, trademarks, service marks, etc. in this publication does not imply, even in the absence of a specific statement, that such names are exempt from the relevant protective laws and regulations and therefore free for general use. The publisher, the authors and the editors are safe to assume that the advice and information in this book are believed to be true and accurate at the date of publication. Neither the publisher nor the authors or the editors give a warranty, express or implied, with respect to the material contained herein or for any errors or omissions that may have been made. -

Am Radio Transmission

AM RADIO TRANSMISSION 6.101 Final Project TIMI OMTUNDE SPRING 2020 AM Radio Transmission 6.101 Final Project Table of Contents 1. Abstract 2. Introduction 3. Goals a. Base b. Expected c. Stretch 4. Block Diagram 5. Schematic 6. PCB Layout 7. Design and Overview 8. Subsystem Overview a. Transmitter i. Oscillator ii. Modulator iii. RF Amplifier iv. Antenna b. Receiver c. Battery Charger 9. Testing and Debugging 10. Challenges and Improvements 11. Conclusion 12. Acknowledgments 13. Appendix Omotunde 1 AM Radio Transmission 6.101 Final Project AM Radio Transmission Abstract Amplitude modulation (AM) radio transmissions are commonly used in commercial and private applications, where the aim is to broadcast to an audience - communications of any type, whether it be someone speaking, Morse code, or even ambient noise. In AM radio frequencies (RF) transmissions, the amplitude of the wave is modulated and encoded with the transmitted sound, while the frequency is kept the same. Furthermore, AM radio transmissions can occur on different frequencies, with broadcasts of the same frequency interfering with each other. Therefore, it is important to select a unique – or as unique as possible – frequency band in order to transmit clean, interference free, communications. And currently, many 1-way and 2-way radios, with transmission ability have some digital component in order to improve different aspects of the radio. Thus, for my 6.101 final project, I have built a fully analog circuit, in keeping with the theme of the class, that can be used to broadcast to specific AM frequencies. Thus, the goal is to broadcast as far as possible while minimizing the power consumed. -

Radio Frequency and Modulation Systems—Part 1: Earth Stations

CCSDS Historical Document This document’s Historical status indicates that it is no longer current. It has either been replaced by a newer issue or withdrawn because it was deemed obsolete. Current CCSDS publications are maintained at the following location: http://public.ccsds.org/publications/ CCSDS HISTORICAL DOCUMENT RECOMMENDATIONS FOR SPACE DATA SYSTEM STANDARDS RADIO FREQUENCY AND MODULATION SYSTEMS— PART 1 EARTH STATIONS AND SPACECRAFT CCSDS 401.0-B BLUE BOOK CCSDS HISTORICAL DOCUMENT CCSDS HISTORICAL DOCUMENT CCSDS RECOMMENDATIONS FOR RADIO FREQUENCY AND MODULATION SYSTEMS Earth Stations and Spacecraft AUTHORITY Issue:: Blue Book, Issue 1 & 2 Recs. First Release: September 1989 Latest Revision: May 2000 Revision Meeting: N/A Meeting Location: N/A This document has been approved for publication by the Management Council of the Consultative Committee for Space Data Systems (CCSDS) and represents the consensus technical agreement of the participating CCSDS Member Agencies. The procedure for review and authorization of CCSDS Recommendations is detailed in Reference [1] and the record of Agency participation in the authorization of this document can be obtained from the CCSDS Secretariat at the address below. This document is published and maintained by: CCSDS Secretariat Program Integration Division (Code MT) National Aeronautics and Space Administration Washington, DC 20546, USA CCSDS 401 B Page i May 2000 CCSDS HISTORICAL DOCUMENT CCSDS HISTORICAL DOCUMENT CCSDS RECOMMENDATIONS FOR RADIO FREQUENCY AND MODULATION SYSTEMS Earth Stations and Spacecraft STATEMENT OF INTENT The Consultative Committee for Space Data Systems (CCSDS) is an organization officially established by the management of member space Agencies. The Committee meets periodically to address data systems problems that are common to all participants, and to formulate sound technical solutions to these problems. -

Radio Theory the Basics Radio Theory the Basics Radio Wave Propagation

Radio Theory The Basics Radio Theory The Basics Radio Wave Propagation Radio Theory The Basics Electromagnetic Spectrum Radio Theory The Basics Radio Theory The Basics • Differences between Very High Frequency (VHF) and Ultra High Frequency (UHF). • Difference between Amplitude Modulation (AM) and Frequency Modulation (FM). • Interference and the best methods to reduce it. • The purpose of a repeater and when it would be necessary. Radio Theory The Basics VHF - Very High Frequency • Range: 30 MHz - 300 MHz • Government and public service operate primarily at 150 MHz to 174 MHz for incidents • 150 MHz to 174 MHz used extensively in NIFC communications equipment • VHF has the advantage of being able to pass through bushes and trees • VHF has the disadvantage of not reliably passing through buildings • 2 watt VHF hand-held radio is capable of transmitting understandably up to 30 miles, line-of-sight Radio Theory The Basics VHF ABSOLUTE MAXIMUM RANGE OF LINE-OF-SITE PORTABLE RADIO COMMUNICATIONS 165 MHz CAN TRANSMIT ABOUT 200 MILES Radio Theory The Basics UHF - Ultra High Frequency • 300 MHz - 3,000 MHz • Government and public safety operate primarily at 400 MHz to 470 MHz for incidents Radio Theory The Basics UHF - Ultra High Frequency • 400 MHz to 420 MHz used in NIFC equipment primarily for logistical communications and linking • Advantage of being able to transmit great distances (2 watt UHF hand-held can transmit 50 miles maximum…line-of-sight in ideal conditions) • UHF signals tend to “bounce” off of buildings and objects, making them -

Inoc-2-Radio.Pdf

2 Radio When radio transmission Was first proposed more than 100 years ago, even Thomas Edison was skeptical. Upon hearing that his former assistant, Reginald A. Fessenden, thought it was possible to transmit voices wirelessly, Edison replied, “Fezzie, what do you say are men’s chances of jumping over the moon? I think one as likely as the other.”1 For his first transmission, in December 1906 from Brant Rock, Massachusetts, Fessenden broadcast a Christ- mas-themed speech and music. It mainly reached radio operators aboard ships, who expressed surprise at hearing “angels’ voices” on their wireless radios.2 But the medium vividly demonstrated its power in 1912, when the sinking Titanic used radio to send out one of the first SOS signals ever sent from a ship. One nearby ship, theCarpathia , heard the distress call through its wireless receiver and rescued 712 passengers from the ocean. When the Titanic survivors arrived in New York City, they went to thank Guglielmo Marconi, regarded as the “father of radio,” for their lives.3 But it was a boxing match in 1921 between Jack Dempsey and Frenchman George Carpentier that trans- formed radio from a one-to-one into a one-to-many medium. Technicians, according to one scholar, connected a phone with “an extremely long wire that ran out of the stadium and all the way to Hoboken, New Jersey, to a giant radio transmitter. To that transmitter was attached a giant antenna, some six hundred feet long, strung between a clock tower and a nearby building.” The blow-by-blow coverage was beamed to hundreds of thousands of listeners in “radio halls” in 61 cities.4 As the Wireless Age put it: “Instantly, through the ears of an expectant public, a world event had been ‘pictured’ in all its thrilling details...