Biomechanical Contributions of Posterior Deltoid and Teres Minor in the Context of Axillary Nerve Injury: a Computational Study Dustin L

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

M1 – Muscled Arm

M1 – Muscled Arm See diagram on next page 1. tendinous junction 38. brachial artery 2. dorsal interosseous muscles of hand 39. humerus 3. radial nerve 40. lateral epicondyle of humerus 4. radial artery 41. tendon of flexor carpi radialis muscle 5. extensor retinaculum 42. median nerve 6. abductor pollicis brevis muscle 43. flexor retinaculum 7. extensor carpi radialis brevis muscle 44. tendon of palmaris longus muscle 8. extensor carpi radialis longus muscle 45. common palmar digital nerves of 9. brachioradialis muscle median nerve 10. brachialis muscle 46. flexor pollicis brevis muscle 11. deltoid muscle 47. adductor pollicis muscle 12. supraspinatus muscle 48. lumbrical muscles of hand 13. scapular spine 49. tendon of flexor digitorium 14. trapezius muscle superficialis muscle 15. infraspinatus muscle 50. superficial transverse metacarpal 16. latissimus dorsi muscle ligament 17. teres major muscle 51. common palmar digital arteries 18. teres minor muscle 52. digital synovial sheath 19. triangular space 53. tendon of flexor digitorum profundus 20. long head of triceps brachii muscle muscle 21. lateral head of triceps brachii muscle 54. annular part of fibrous tendon 22. tendon of triceps brachii muscle sheaths 23. ulnar nerve 55. proper palmar digital nerves of ulnar 24. anconeus muscle nerve 25. medial epicondyle of humerus 56. cruciform part of fibrous tendon 26. olecranon process of ulna sheaths 27. flexor carpi ulnaris muscle 57. superficial palmar arch 28. extensor digitorum muscle of hand 58. abductor digiti minimi muscle of hand 29. extensor carpi ulnaris muscle 59. opponens digiti minimi muscle of 30. tendon of extensor digitorium muscle hand of hand 60. superficial branch of ulnar nerve 31. -

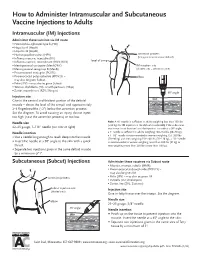

How to Administer Intramuscular and Subcutaneous Vaccines to Adults

How to Administer Intramuscular and Subcutaneous Vaccine Injections to Adults Intramuscular (IM) Injections Administer these vaccines via IM route • Haemophilus influenzae type b (Hib) • Hepatitis A (HepA) • Hepatitis B (HepB) • Human papillomavirus (HPV) acromion process (bony prominence above deltoid) • Influenza vaccine, injectable (IIV) • level of armpit • Influenza vaccine, recombinant (RIV3; RIV4) • Meningococcal conjugate (MenACWY) IM injection site • Meningococcal serogroup B (MenB) (shaded area = deltoid muscle) • Pneumococcal conjugate (PCV13) • Pneumococcal polysaccharide (PPSV23) – elbow may also be given Subcut • Polio (IPV) – may also be given Subcut • Tetanus, diphtheria (Td), or with pertussis (Tdap) • Zoster, recombinant (RZV; Shingrix) 90° angle Injection site skin Give in the central and thickest portion of the deltoid muscle – above the level of the armpit and approximately subcutaneous tissue 2–3 fingerbreadths (~2") below the acromion process. See the diagram. To avoid causing an injury, do not inject muscle too high (near the acromion process) or too low. Needle size Note: A ⅝" needle is sufficient in adults weighing less than 130 lbs (<60 kg) for IM injection in the deltoid muscle only if the subcutane- 22–25 gauge, 1–1½" needle (see note at right) ous tissue is not bunched and the injection is made at a 90° angle; Needle insertion a 1" needle is sufficient in adults weighing 130–152 lbs (60–70 kg); a 1–1½" needle is recommended in women weighing 153–200 lbs • Use a needle long enough to reach deep into the muscle. (70–90 kg) and men weighing 153–260 lbs (70–118 kg); a 1½" needle • Insert the needle at a 90° angle to the skin with a quick is recommended in women weighing more than 200 lbs (91 kg) or thrust. -

MRI Patterns of Shoulder Denervation: a Way to Make It Easy

MRI Patterns Of Shoulder Denervation: A Way To Make It Easy Poster No.: C-2059 Congress: ECR 2018 Type: Educational Exhibit Authors: E. Rossetto1, P. Schvartzman2, V. N. Alarcon2, M. E. Scherer2, D. M. Cecchi3, F. M. Olivera Plata4; 1Buenos Aires, Capital Federal/ AR, 2Buenos Aires/AR, 3Capital Federal, Buenos Aires/AR, 4Ciudad Autonoma de Buenos Aires/AR Keywords: Musculoskeletal joint, Musculoskeletal soft tissue, Neuroradiology peripheral nerve, MR, Education, eLearning, Edema, Inflammation, Education and training DOI: 10.1594/ecr2018/C-2059 Any information contained in this pdf file is automatically generated from digital material submitted to EPOS by third parties in the form of scientific presentations. References to any names, marks, products, or services of third parties or hypertext links to third- party sites or information are provided solely as a convenience to you and do not in any way constitute or imply ECR's endorsement, sponsorship or recommendation of the third party, information, product or service. ECR is not responsible for the content of these pages and does not make any representations regarding the content or accuracy of material in this file. As per copyright regulations, any unauthorised use of the material or parts thereof as well as commercial reproduction or multiple distribution by any traditional or electronically based reproduction/publication method ist strictly prohibited. You agree to defend, indemnify, and hold ECR harmless from and against any and all claims, damages, costs, and expenses, including attorneys' fees, arising from or related to your use of these pages. Please note: Links to movies, ppt slideshows and any other multimedia files are not available in the pdf version of presentations. -

Kinematics Based Physical Modelling and Experimental Analysis of The

INGENIERÍA E INVESTIGACIÓN VOL. 37 N.° 3, DECEMBER - 2017 (115-123) DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.15446/ing.investig.v37n3.63144 Kinematics based physical modelling and experimental analysis of the shoulder joint complex Modelo físico basado en cinemática y análisis experimental del complejo articular del hombro Diego Almeida-Galárraga1, Antonio Ros-Felip2, Virginia Álvarez-Sánchez3, Fernando Marco-Martinez4, and Laura Serrano-Mateo5 ABSTRACT The purpose of this work is to develop an experimental physical model of the shoulder joint complex. The aim of this research is to validate the model built and identify the forces on specified positions of this joint. The shoulder musculoskeletal structures have been replicated to evaluate the forces to which muscle fibres are subjected in different equilibrium positions: 60º flexion, 60º abduction and 30º abduction and flexion. The physical model represents, quite accurately, the shoulder complex. It has 12 real degrees of freedom, which allows motions such as abduction, flexion, adduction and extension and to calculate the resultant forces of the represented muscles. The built physical model is versatile and easily manipulated and represents, above all, a model for teaching applications on anatomy and shoulder joint complex biomechanics. Moreover, it is a valid research tool on muscle actions related to abduction, adduction, flexion, extension, internal and external rotation motions or combination among them. Keywords: Physical model, shoulder joint, experimental technique, tensions analysis, biomechanics, kinetics, cinematic. RESUMEN Este trabajo consiste en desarrollar un modelo físico experimental del complejo articular del hombro. El objetivo en esta investigación es validar el modelo construido e identificar las fuerzas en posiciones específicas de esta articulación. -

Neurotization to Innervate the Deltoid and Biceps: 3 Cases

SCIENTIFIC ARTICLE Neurotization to Innervate the Deltoid and Biceps: 3 Cases Christopher J. Dy, MD, MSPH, Alison Kitay, MD, Rohit Garg, MBBS, Lana Kang, MD, Joseph H. Feinberg, MD, Scott W. Wolfe, MD Purpose To describe our experience using direct muscle neurotization as a treatment adjunct during delayed surgical reconstruction for traumatic denervation injuries. Methods Three patients who had direct muscle neurotization were chosen from a consecutive series of patients undergoing reconstruction for brachial plexus injuries. The cases are presented in detail, including long-term clinical follow-up at 2, 5, and 10 years with accompanying postoperative electrodiagnostic studies. Postoperative motor strength using British Medical Research Council grading and active range of motion were retrospectively extracted from the clinical charts. Results Direct muscle neurotization was performed into the deltoid in 2 cases and into the biceps in 1 case after delays of up to 10 months from injury. Two patients had recovery of M4 strength, and the other patient had recovery of M3 strength. All 3 patients had evidence on electrodiagnostic studies of at least partial muscle reinnervation after neurotization. Conclusions Direct muscle neurotization has shown promising results in numerous basic science investigations and a limited number of clinical cases. The current series provides additional clinical and electrodiagnostic evidence that direct muscle neurotization can successfully provide reinnervation, even after lengthy delays from injury to surgical treatment. Clinical relevance Microsurgeons should consider direct muscle neurotization as a viable adjunct treatment and part of a comprehensive reconstructive plan, especially for injuries associated with avulsion of the distal nerve stump from its insertion into the muscle. -

Deltoid Strengthening

Andrew Robert Malarkey, D.O. Shoulder, Elbow and Hand Surgery www.ohioshouldertohand.com 800-824-9861 The following sets of exercises are designed to strengthen the outer muscle of your shoulder (deltoid muscle). Improving your deltoid strength is the key to achieving improved strength and function of your shoulder. Key Points: • Sets of 10 • 3-5 times each day. • Stop exercises if your pain increases or you do not feel well. • Expect to see improvement by 6-12 weeks Exercises: 1. Warm up with Pendulum Exercise -- While standing, bend forward and let your arm dangle free and perform gentle pendulum movement for about 2-3 minutes. This will help you in relieving pain and free up your muscles around the shoulder. 2. Lie down flat on your back, with a pillow supporting your head. 3. Raise your weak arm to 90 degrees vertical, using the stronger arm to assist if necessary. The elbow should be straight and in line with your ear. 4. Hold your arm in this upright position with its own strength. 5. Slowly with your fingers, wrist and elbow straight move the arm forwards and backwards in line with the outside of the leg, as per diagram. This should be a slow gentle movement. Keep the Andrew Robert Malarkey, D.O. Shoulder, Elbow and Hand Surgery www.ohioshouldertohand.com 800-824-9861 movement smooth and continuous for 5 minutes or until fatigue. 6. As you get more confidence in controlling your shoulder movement, gradually increase the amplitude of movement until your arm will move from the side of your thigh to above your head, touching the bed (behind your head), and returning to your side. -

Deltoid Triceps Transfer and Functional Independence of People with Tetraplegia

Spinal Cord (2000) 38, 435 ± 441 ã 2000 International Medical Society of Paraplegia All rights reserved 1362 ± 4393/00 $15.00 www.nature.com/sc Deltoid triceps transfer and functional independence of people with tetraplegia AL Dunkerley*,1, A Ashburn1 and EL Stack1 1University Rehabilitation Research Unit, University of Southampton, UK Study design: Matched case control study. Setting: Two regional spinal units ± Salisbury, UK (surgical centre) and London, UK (control centre). Objective: To compare the functional independence and wheelchair mobility of spinal cord injured subjects, post deltoid triceps transfer, with matched control subjects. Methods: Two matched groups of subjects, with tetraplegia resulting in triceps paralysis, were studied. The surgical group consisted of ®ve of the six patients who had previously undergone deltoid triceps transfer at Salisbury. The control group (n=6) had not undergone surgical intervention but were comparable with respect to level of lesion, age, age at injury and duration of disability. All subjects completed standardised assessments of activities of daily living (Functional Independence Measure ± FIM) and wheelchair mobility (10 m push and ®gure of 8 push). Surgical subjects completed additional questions, regarding the perceived eects of surgery on function. Results: It was not possible to demonstrate absolute functional dierences with the chosen outcome measures in this small series of matched case controls. All surgical subjects cited speci®c functional improvements since surgery and recommended the procedure. However the FIM lacked sucient sensitivity to detect these changes. Conclusion: Further investigation of the functional outcome of deltoid triceps transfer in tetraplegia is warranted. Development of more sensitive outcome measures would be useful. -

The Deltoid, a Forgotten Muscle of the Shoulder

Skeletal Radiol DOI 10.1007/s00256-013-1667-7 REVIEW ARTICLE The deltoid, a forgotten muscle of the shoulder Thomas Moser & Junie Lecours & Johan Michaud & Nathalie J. Bureau & Raphaël Guillin & Étienne Cardinal Received: 17 February 2013 /Revised: 29 May 2013 /Accepted: 30 May 2013 # ISS 2013 Abstract The deltoid is a fascinating muscle with a signif- Keywords Deltoid muscle . Shoulder . Anatomy . Tears . icant role in shoulder function. It is comprised of three Nerve injuries distinct portions (anterior or clavicular, middle or acromial, and posterior or spinal) and acts mainly as an abductor of the shoulder and stabilizer of the humeral head. Deltoid tears are Introduction not infrequently associated with large or massive rotator cuff tears and may further jeopardize shoulder function. A variety The deltoid is an essential, although lesser considered, muscle of other pathologies may affect the deltoid muscle including of the shoulder and thus it is rarely mentioned in MRI reports, enthesitis, calcific tendinitis, myositis, infection, tumors, and which tend to focus on rotator cuff tendon and muscles. chronic avulsion injury. Contracture of the deltoid following In this paper, we aimed to review the normal anatomy and repeated intramuscular injections could present with pro- function of the deltoid muscle and to describe imaging gressive abduction deformity and winging of the scapula. features of various pathologies. The deltoid muscle and its innervating axillary nerve may be injured during shoulder surgery, which may have disastrous functional consequences. Axillary neuropathies leading to del- Anatomy and function toid muscle dysfunction include traumatic injuries, quadrilat- eral space and Parsonage–Turner syndromes, and cause dener- Overview and functional anatomy vation of the deltoid muscle. -

A Rare Shoulder DAVID J

Postgrad Med J: first published as 10.1136/pgmj.43.502.541 on 1 August 1967. Downloaded from Case reports 541 A rare shoulder DAVID J. FULLER M.B., B.S. Senior House Officer, Rowley Bristow Orthopaedic Hospital, Pyrford, Surrey RUPTURE of the supraspinatus component of the In October, 3 months later, he presented to this rotator cuff is not an uncommon occurrence. The unit complaining of disabling loss of voluntary diagnosis and treatment of this event is well movement at the left shoulder joint. Pain was not a accounted for in surgical texts. An entirely symptom. unrelated condition which is also thoroughly des- Examination revealed a right shoulder of nor- cribed in the literature is traumatic paralysis of mal contours with full active range of movement the deltoid muscle. The performance of abduction and full power. On the left side the deltoid muscle at the shoulder joint is normally achieved by was completely wasted. There was no anaesthesia supraspinatus and deltoid working in harmony in the area supplied by the superficial branch of and should either of the above two events occur, the circumflex nerve. The left shoulder could be such abduction that remains possible is very much moved passively without pain through the entire a function of the other intact mechanism. normal range. The active movements, however, Isolated deltoid paralysis, in fact, results in very of flexion, extension and abduction were reduced little disability whereas a complete tear of the to some 150 each. When the left arm was passively supraspinatus tendon usually represents a severe guided to a point 20° or more from the trunk and handicap. -

Muscles of the Upper Extremity

MUSCLES OF THE UPPER EXTREMITY: Movement of the shoulder and arm: Anterior Axioappendicular Muscles: Pectoralis major O: (clavicular head) medial 1/2 of Clavicle, All fibers : Adducts and medially rotates humerus at Nerves: Lateral and medial pectoral nerves (Sternocostal) Sternum, Anterior suface of shoulder. Also, draws scapula anteriorly and inferiorly Roots: Clavicular (C 5-6), Sternocostal (C 7-8, T1) Ribs 1-6, aponeurosis of External Oblique Clavicular and Sterno fibers : flexes and I: Lateral lip of intertubercular sulcus horizonly adducts humerus. of humerus. Costal fibers : extends humerus. S: Adduction: Latissimus Dorsi, Teres (major & minor), Extension: Posterior deltoid, Latissimus dorsi, Medial rotation: Latissimus Dorsi, Anterior Deltoid, Infraspinatus, Long head Triceps, coracobrachialis teres major, Long head Tricep Teres major, subscapularis A: Abduction: All 3 parts of Deltoid, Supraspinatus, Flexion: Anterior Deltoid, Biceps brachii Lateral rotation: Infraspinatus, Teres minor, coracobrachialis Posterior Deltoid Pectoralis minor O: Anterior superior surface of ribs 3-5 With ribs fixed: Nerve: Medial pectoral nerves sometimes rib 6 Depresses, abducts, downwardly rotate scapula. Roots: (C8 and T1) I: Coracoid process of scapula. With scapula fixed: Elevates 3rd through 5th ribs during forced inspiration. S: Abduction: Serratus Anterior Depression: Lower Trapezius, Serratus anterior Downward rotation: Rhomboid major and minor, Levator scapula, A: Adduction: Romboideus Major and Minor, middle Tapezius Elevation : Upper Trapezius, -

An Electromyographic Analysis of Lateral Raise Variations and Frontal Raise in Competitive Bodybuilders

International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health Article An Electromyographic Analysis of Lateral Raise Variations and Frontal Raise in Competitive Bodybuilders Giuseppe Coratella 1,* , Gianpaolo Tornatore 1 , Stefano Longo 1 , Fabio Esposito 1,2 and Emiliano Cè 1,2 1 Department of Biomedical Sciences for Health, Università degli Studi di Milano, 20133 Milano, Italy; [email protected] (G.T.); [email protected] (S.L.); [email protected] (F.E.); [email protected] (E.C.) 2 IRCSS Galeazzi Orthopaedic Institute, 20161 Milano, Italy * Correspondence: [email protected] Received: 7 July 2020; Accepted: 18 August 2020; Published: 19 August 2020 Abstract: The present study examined the muscle activation in lateral raise with humerus rotated externally (LR-external), neutrally (LR-neutral), internally (LR-internal), with flexed elbow (LR-flexed) and frontal raise during both the concentric and eccentric phase. Ten competitive bodybuilders performed the exercises. Normalized surface electromyographic root mean square (sEMG RMS) was obtained from anterior, medial, and posterior deltoid, pectoralis major, upper trapezius, and triceps brachii. During the concentric phase, anterior deltoid and posterior deltoid showed greater sEMG RMS in frontal raise (effect size (ES)-range: 1.78/9.25)) and LR-internal (ES-range: 10.79/21.34), respectively, vs. all other exercises. Medial deltoid showed greater sEMG RMS in LR-neutral than LR-external (ES: 1.47 (95% confidence-interval—CI: 0.43/2.38)), frontal raise (ES: 10.28(95% CI: 6.67/13.01)), and LR-flexed (ES: 6.41(95% CI: 4.04/8.23)). Pectoralis major showed greater sEMG RMS in frontal raise vs. -

Anatomy, Shoulder and Upper Limb, Deltoid Muscle

NCBI Bookshelf. A service of the National Library of Medicine, National Institutes of Health. StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2018 Jan-. Anatomy, Shoulder and Upper Limb, Deltoid Muscle Authors Adel Elzanie; Matthew Varacallo1. Affiliations 1 Department of Orthopaedic Surgery, University of Kentucky School of Medicine Last Update: December 21, 2018. Introduction The deltoid muscle is a large triangular shaped muscle associated with the human shoulder girdle, explicitly located in the proximal upper extremity. The shoulder girdle is composed of the following osseous components[1][2][3] Proximal humerus Scapula anatomic components of the scapula also include the glenoid, acromion, coracoid process Clavicle The shoulder girdle musculature, in addition to the deltoid muscle itself, includes the following[4][5][6][7][8] Rotator cuff (supraspinatus, infraspinatus, teres minor, subscapularis) Trapezius and other periscapular stabilizing muscles Triceps Latissimus dorsi Pectoralis major/minor The deltoid is composed of anterior (or clavicular fibers), lateral (or acromial fibers), and posterior (or spinal fibers).[9] Structure and Function The deltoid is a triangular muscle. It’s base (or origin) attaches to the spine of the scapula and lateral third of the clavicle. This U-shaped origin point mirrors the insertion point for the trapezius muscle. It’s apex (or insertion) attaches to the lateral side of the body of the humerus, on a point known as the deltoid tuberosity.[9] The deltoid divides into three distinct parts (anterior, lateral, and posterior). When all three parts contracts simultaneously, the deltoid will assist in abducting the arm past 15 degrees. It cannot initiate abduction because the direction of pull of the deltoid muscle is parallel to the axis of the humerus.