Anatomy, Shoulder and Upper Limb, Deltoid Muscle

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Anatomical Variants in the Termination of the Cephalic Vein Stoyan Novakov1*, Elena Krasteva2

Institute of Experimental Morphology, Pathology and Anthropology with Museum Bulgarian Anatomical Society Acta morphologica et anthropologica, 25 (3-4) Sofia • 2018 Anatomical Variants in the Termination of the Cephalic Vein Stoyan Novakov1*, Elena Krasteva2 1 Department of Anatomy, Histology and Embryology, 2Department of Propaedeutics of Surgical Di- seases, Medical Faculty, Medical University of Plovdiv * Corresponding author e-mail: [email protected] Jugulocephalic vein is atavistic structure which is very rare. The low incidence of the variations of the cephalic vein in deltopectoral triangle and its position on the anterior surface of the clavicle and the neck doesn’t make it less important for the clinical practice. Phylo- and ontogenesis explain the formation of the above mentioned variations. We followed the pattern of the cephalic vein in its proximal part and termination to describe possible variations. In this long term study on 140 upper limbs of 70 cadavers, 4 or 2,9% of the cephalic veins were variable. The direct empting of the cephalic vein into internal jugular is an exception with few descriptions at the moment. The rareness of this anatomical variation doesn’t make it less important for clinical practice. It is described as a possible obstacle in catheter implantation, clavicle fractures and creation of arteriovenous fistula in patients on hemodialysis. Key words:cadavers, human anatomy variation, cephalic vein, external jugular vein, jugulocephalic vein Introduction Cephalic vein (CV) belongs to the group of superficial veins of the upper limb. It usually forms over the anatomical snuff-box on the radial side of the wrist from the radial end of the dorsal venous plexus. -

Pectoral Muscles 1. Remove the Superficial Fascia Overlying the Pectoralis Major Muscle (Fig

BREAST, PECTORAL REGION, AND AXILLA LAB (Grant's Dissector (16th Ed.) pp. 28-38) TODAY’S GOALS: 1. Identify the major structural and tissue components of the female breast, including its blood supply. 2. Identify examples of axillary lymph nodes and understand the lymphatic drainage of the breast. 3. Identify the pectoralis major, pectoralis minor, and serratus anterior muscles. Demonstrate their bony attachments, nerve supply, and actions. 4. Identify the walls and associated muscles of the axilla. 5. Identify the axillary sheath, axillary vein, and the 6 major branches of the axillary artery. 6. Identify and trace the cords of the brachial plexus and their branches. DISSECTION NOTES: The donor should be in the supine position. Breast 1. The breast or mammary gland is a modified sweat gland embedded in the superficial fascia overlying the anterior chest wall. Refer to Fig. 2.5A for incisions for reflecting skin of the pectoral region to the mid-arm. Do this bilaterally. Within the superficial fascia in front of the shoulder and along the lateral and lower medial portions of the arm locate the cephalic and basilic veins and preserve these for now. Observe the course of the cephalic vein from the arm into the deltopectoral groove between the deltoid and pectoralis major muscles. 2. For those who have a female donor, mobilize the breast by inserting your fingers behind it within the retromammary space and separate it from the underlying deep fascia of the pectoralis major (see Fig. 2.7). An extension of breast tissue (axillary tail) from the superolateral (upper outer) quadrant often extends around the lateral border of the pectoralis major muscle into the axilla. -

By the Authors. These Guidelines Will Be Usefulas an Aid in Diagnosing

Kroeber Anthropological Society Papers, Nos. 71-72, 1990 Humeral Morphology of Achondroplasia Rina Malonzo and Jeannine Ross Unique humeral morphologicalfeatures oftwo prehistoric achondroplastic adult individuals are des- cribed. Thesefeatures are compared to the humerus ofa prehistoric non-achondroplastic dwarfand to the humeri ofa normal humanpopulation sample. A set ofunique, derived achondroplastic characteris- tics ispresented. The non-achondroplastic individual is diagnosed as such based on guidelines created by the authors. These guidelines will be useful as an aid in diagnosing achondroplastic individualsfrom the archaeological record. INTRODUCTION and 1915-2-463) (Merbs 1980). The following paper describes a set of humeral morphological For several decades dwarfism has been a characteristics which can be used as a guide to prominent topic within the study of paleopathol- identifying achondroplastic individuals from the ogy. It has been represented directly by skeletal archaeological record. evidence and indirectly by artistic representation in the archaeological record (Hoffman and Brunker 1976). Several prehistoric Egyptian and MATERIALS AND METHODS Native American dwarfed skeletons have been recorded, indicating that this pathology is not A comparative population sample, housed by linked solely with modem society (Brothwell and the Lowie Museum of Anthropology (LMA) at Sandison 1967; Hoffman and Brunker 1976; the University of California at Berkeley, was Niswander et al. 1975; Snow 1943). Artifacts derived from a random sample forming a total of such as paintings, tomb illustrations and statues sixty adult individuals (thirty males and thirty of dwarfed individuals have been discovered in females) from six different prehistoric ar- various parts of the world. However, interpreta- chaeological sites within California. Two tions of such artifacts are speculative, for it is achondroplastic adult individuals from similar necessary to allow artistic license for individualis- contexts, specimen number 6670 (spc. -

The Clinical Anatomy of the Cephalic Vein in the Deltopectoral Triangle

Folia Morphol. Vol. 67, No. 1, pp. 72–77 Copyright © 2008 Via Medica O R I G I N A L A R T I C L E ISSN 0015–5659 www.fm.viamedica.pl The clinical anatomy of the cephalic vein in the deltopectoral triangle M. Loukas1, 2, C.S. Myers1, Ch.T. Wartmann1, R.S. Tubbs3, T. Judge1, B. Curry1, R. Jordan1 1Department of Anatomical Sciences, St. George’s University, School of Medicine, Grenada, West Indies 2Department of Education and Development, Harvard Medical School, Boston MA, USA 3Department of Cell Biology and Pediatric Neurosurgery, University of Alabama at Brimingham, AL, USA [Received 19 June 2007; Revised 3 January 2008; Accepted 7 January 2008] Identification and recognition of the cephalic vein in the deltopectoral triangle is of critical importance when considering emergency catheterization proce- dures. The aim of our study was to conduct a cadaveric study to access data regarding the topography and the distribution patterns of the cephalic vein as it relates to the deltopectoral triangle. One hundred formalin fixed cadavers were examined. The cephalic vein was found in 95% (190 right and left) spec- imens, while in the remaining 5% (10) the cephalic vein was absent. In 80% (152) of cases the cephalic vein was found emerging superficially in the lateral portion of the deltopectoral triangle. In 30% (52) of these 152 cases the ceph- alic vein received one tributary within the deltopectoral triangle, while in 70% (100) of the specimens it received two. In the remaining 20% (38) of cases the cephalic vein was located deep to the deltopectoral fascia and fat and did not emerge through the deltopectoral triangle but was identified medially to the coracobrachialis and inferior to the medial border of the deltoid. -

M1 – Muscled Arm

M1 – Muscled Arm See diagram on next page 1. tendinous junction 38. brachial artery 2. dorsal interosseous muscles of hand 39. humerus 3. radial nerve 40. lateral epicondyle of humerus 4. radial artery 41. tendon of flexor carpi radialis muscle 5. extensor retinaculum 42. median nerve 6. abductor pollicis brevis muscle 43. flexor retinaculum 7. extensor carpi radialis brevis muscle 44. tendon of palmaris longus muscle 8. extensor carpi radialis longus muscle 45. common palmar digital nerves of 9. brachioradialis muscle median nerve 10. brachialis muscle 46. flexor pollicis brevis muscle 11. deltoid muscle 47. adductor pollicis muscle 12. supraspinatus muscle 48. lumbrical muscles of hand 13. scapular spine 49. tendon of flexor digitorium 14. trapezius muscle superficialis muscle 15. infraspinatus muscle 50. superficial transverse metacarpal 16. latissimus dorsi muscle ligament 17. teres major muscle 51. common palmar digital arteries 18. teres minor muscle 52. digital synovial sheath 19. triangular space 53. tendon of flexor digitorum profundus 20. long head of triceps brachii muscle muscle 21. lateral head of triceps brachii muscle 54. annular part of fibrous tendon 22. tendon of triceps brachii muscle sheaths 23. ulnar nerve 55. proper palmar digital nerves of ulnar 24. anconeus muscle nerve 25. medial epicondyle of humerus 56. cruciform part of fibrous tendon 26. olecranon process of ulna sheaths 27. flexor carpi ulnaris muscle 57. superficial palmar arch 28. extensor digitorum muscle of hand 58. abductor digiti minimi muscle of hand 29. extensor carpi ulnaris muscle 59. opponens digiti minimi muscle of 30. tendon of extensor digitorium muscle hand of hand 60. superficial branch of ulnar nerve 31. -

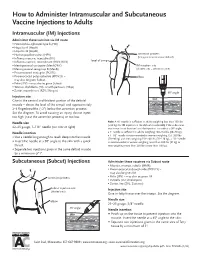

How to Administer Intramuscular and Subcutaneous Vaccines to Adults

How to Administer Intramuscular and Subcutaneous Vaccine Injections to Adults Intramuscular (IM) Injections Administer these vaccines via IM route • Haemophilus influenzae type b (Hib) • Hepatitis A (HepA) • Hepatitis B (HepB) • Human papillomavirus (HPV) acromion process (bony prominence above deltoid) • Influenza vaccine, injectable (IIV) • level of armpit • Influenza vaccine, recombinant (RIV3; RIV4) • Meningococcal conjugate (MenACWY) IM injection site • Meningococcal serogroup B (MenB) (shaded area = deltoid muscle) • Pneumococcal conjugate (PCV13) • Pneumococcal polysaccharide (PPSV23) – elbow may also be given Subcut • Polio (IPV) – may also be given Subcut • Tetanus, diphtheria (Td), or with pertussis (Tdap) • Zoster, recombinant (RZV; Shingrix) 90° angle Injection site skin Give in the central and thickest portion of the deltoid muscle – above the level of the armpit and approximately subcutaneous tissue 2–3 fingerbreadths (~2") below the acromion process. See the diagram. To avoid causing an injury, do not inject muscle too high (near the acromion process) or too low. Needle size Note: A ⅝" needle is sufficient in adults weighing less than 130 lbs (<60 kg) for IM injection in the deltoid muscle only if the subcutane- 22–25 gauge, 1–1½" needle (see note at right) ous tissue is not bunched and the injection is made at a 90° angle; Needle insertion a 1" needle is sufficient in adults weighing 130–152 lbs (60–70 kg); a 1–1½" needle is recommended in women weighing 153–200 lbs • Use a needle long enough to reach deep into the muscle. (70–90 kg) and men weighing 153–260 lbs (70–118 kg); a 1½" needle • Insert the needle at a 90° angle to the skin with a quick is recommended in women weighing more than 200 lbs (91 kg) or thrust. -

Bone Limb Upper

Shoulder Pectoral girdle (shoulder girdle) Scapula Acromioclavicular joint proximal end of Humerus Clavicle Sternoclavicular joint Bone: Upper limb - 1 Scapula Coracoid proc. 3 angles Superior Inferior Lateral 3 borders Lateral angle Medial Lateral Superior 2 surfaces 3 processes Posterior view: Acromion Right Scapula Spine Coracoid Bone: Upper limb - 2 Scapula 2 surfaces: Costal (Anterior), Posterior Posterior view: Costal (Anterior) view: Right Scapula Right Scapula Bone: Upper limb - 3 Scapula Glenoid cavity: Glenohumeral joint Lateral view: Infraglenoid tubercle Right Scapula Supraglenoid tubercle posterior anterior Bone: Upper limb - 4 Scapula Supraglenoid tubercle: long head of biceps Anterior view: brachii Right Scapula Bone: Upper limb - 5 Scapula Infraglenoid tubercle: long head of triceps brachii Anterior view: Right Scapula (with biceps brachii removed) Bone: Upper limb - 6 Posterior surface of Scapula, Right Acromion; Spine; Spinoglenoid notch Suprspinatous fossa, Infraspinatous fossa Bone: Upper limb - 7 Costal (Anterior) surface of Scapula, Right Subscapular fossa: Shallow concave surface for subscapularis Bone: Upper limb - 8 Superior border Coracoid process Suprascapular notch Suprascapular nerve Posterior view: Right Scapula Bone: Upper limb - 9 Acromial Clavicle end Sternal end S-shaped Acromial end: smaller, oval facet Sternal end: larger,quadrangular facet, with manubrium, 1st rib Conoid tubercle Trapezoid line Right Clavicle Bone: Upper limb - 10 Clavicle Conoid tubercle: inferior -

MRI Patterns of Shoulder Denervation: a Way to Make It Easy

MRI Patterns Of Shoulder Denervation: A Way To Make It Easy Poster No.: C-2059 Congress: ECR 2018 Type: Educational Exhibit Authors: E. Rossetto1, P. Schvartzman2, V. N. Alarcon2, M. E. Scherer2, D. M. Cecchi3, F. M. Olivera Plata4; 1Buenos Aires, Capital Federal/ AR, 2Buenos Aires/AR, 3Capital Federal, Buenos Aires/AR, 4Ciudad Autonoma de Buenos Aires/AR Keywords: Musculoskeletal joint, Musculoskeletal soft tissue, Neuroradiology peripheral nerve, MR, Education, eLearning, Edema, Inflammation, Education and training DOI: 10.1594/ecr2018/C-2059 Any information contained in this pdf file is automatically generated from digital material submitted to EPOS by third parties in the form of scientific presentations. References to any names, marks, products, or services of third parties or hypertext links to third- party sites or information are provided solely as a convenience to you and do not in any way constitute or imply ECR's endorsement, sponsorship or recommendation of the third party, information, product or service. ECR is not responsible for the content of these pages and does not make any representations regarding the content or accuracy of material in this file. As per copyright regulations, any unauthorised use of the material or parts thereof as well as commercial reproduction or multiple distribution by any traditional or electronically based reproduction/publication method ist strictly prohibited. You agree to defend, indemnify, and hold ECR harmless from and against any and all claims, damages, costs, and expenses, including attorneys' fees, arising from or related to your use of these pages. Please note: Links to movies, ppt slideshows and any other multimedia files are not available in the pdf version of presentations. -

Trapezius Origin: Occipital Bone, Ligamentum Nuchae & Spinous Processes of Thoracic Vertebrae Insertion: Clavicle and Scapul

Origin: occipital bone, ligamentum nuchae & spinous processes of thoracic vertebrae Insertion: clavicle and scapula (acromion Trapezius and scapular spine) Action: elevate, retract, depress, or rotate scapula upward and/or elevate clavicle; extend neck Origin: spinous process of vertebrae C7-T1 Rhomboideus Insertion: vertebral border of scapula Minor Action: adducts & performs downward rotation of scapula Origin: spinous process of superior thoracic vertebrae Rhomboideus Insertion: vertebral border of scapula from Major spine to inferior angle Action: adducts and downward rotation of scapula Origin: transverse precesses of C1-C4 vertebrae Levator Scapulae Insertion: vertebral border of scapula near superior angle Action: elevates scapula Origin: anterior and superior margins of ribs 1-8 or 1-9 Insertion: anterior surface of vertebral Serratus Anterior border of scapula Action: protracts shoulder: rotates scapula so glenoid cavity moves upward rotation Origin: anterior surfaces and superior margins of ribs 3-5 Insertion: coracoid process of scapula Pectoralis Minor Action: depresses & protracts shoulder, rotates scapula (glenoid cavity rotates downward), elevates ribs Origin: supraspinous fossa of scapula Supraspinatus Insertion: greater tuberacle of humerus Action: abduction at the shoulder Origin: infraspinous fossa of scapula Infraspinatus Insertion: greater tubercle of humerus Action: lateral rotation at shoulder Origin: clavicle and scapula (acromion and adjacent scapular spine) Insertion: deltoid tuberosity of humerus Deltoid Action: -

Kinematics Based Physical Modelling and Experimental Analysis of The

INGENIERÍA E INVESTIGACIÓN VOL. 37 N.° 3, DECEMBER - 2017 (115-123) DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.15446/ing.investig.v37n3.63144 Kinematics based physical modelling and experimental analysis of the shoulder joint complex Modelo físico basado en cinemática y análisis experimental del complejo articular del hombro Diego Almeida-Galárraga1, Antonio Ros-Felip2, Virginia Álvarez-Sánchez3, Fernando Marco-Martinez4, and Laura Serrano-Mateo5 ABSTRACT The purpose of this work is to develop an experimental physical model of the shoulder joint complex. The aim of this research is to validate the model built and identify the forces on specified positions of this joint. The shoulder musculoskeletal structures have been replicated to evaluate the forces to which muscle fibres are subjected in different equilibrium positions: 60º flexion, 60º abduction and 30º abduction and flexion. The physical model represents, quite accurately, the shoulder complex. It has 12 real degrees of freedom, which allows motions such as abduction, flexion, adduction and extension and to calculate the resultant forces of the represented muscles. The built physical model is versatile and easily manipulated and represents, above all, a model for teaching applications on anatomy and shoulder joint complex biomechanics. Moreover, it is a valid research tool on muscle actions related to abduction, adduction, flexion, extension, internal and external rotation motions or combination among them. Keywords: Physical model, shoulder joint, experimental technique, tensions analysis, biomechanics, kinetics, cinematic. RESUMEN Este trabajo consiste en desarrollar un modelo físico experimental del complejo articular del hombro. El objetivo en esta investigación es validar el modelo construido e identificar las fuerzas en posiciones específicas de esta articulación. -

Bones of the Upper and Lower Limb Musculoskeletal Block - Lecture 1

Bones of the Upper and Lower limb Musculoskeletal Block - Lecture 1 Objective: Classify the bones of the three regions of the lower limb (Thigh, leg and foot). Memorize the main features of the – Bones of the thigh (femur & patella) – Bones of the leg (tibia & Fibula) – Bones of the foot (tarsals, metatarsals and phalanges) Recognize the side of the bone. Color index: Important In male’s slides only In female’s slides only Extra information, explanation Editing file Click here for Contact us: useful videos [email protected] Please make sure that you’re familiar with these terms Terms Meaning Example Ridge The long and narrow upper edge, angle, or crest of something The supracondylar ridges (in the distal part of the humerus) Notch An indentation, (incision) on an edge or surface The trochlear notch (in the proximal part of the ulna) Tubercles A nodule or a small rounded projection on the bone (Dorsal tubercle in the distal part of the radius) Fossa A hollow place (The Notch is not complete but the fossa is Subscapular fossa (in the concave part of complete and both of them act as the lock of the joint the scapula) Tuberosity A large prominence on a bone usually serving for Deltoid tuberosity (in the humorous) and it the attachment of muscles or ligaments ( is a bigger projection connects the deltoid muscle than the Tubercle ) Processes A V-shaped indentation (act as the key of the joint) Coracoid process ( in the scapula ) Groove A channel, a long narrow depression sure Spiral (Radial) groove (in the posterior aspect of (the humerus -

Radial Medial Head Triceps Branch Transfer to Axillary Nerve by Axillary Approach Acesso Ao Nervo Axilar Por Via Axilar Anterior

THIEME 134 Review Article | Artigo de Revisão Radial Medial Head Triceps Branch Transfer to Axillary Nerve by Axillary Approach Acesso ao nervo axilar por via axilar anterior José Marcos Pondé 1 Lazaro Santos 2 João Pedro Magalhaes 2 Ana Flavia D ’Álmeida 2 1 Department of Neurosciences and Mental Health, Universidade Address for correspondence José Marcos Pondé, MD, PhD, Av. Paulo Federal da Bahia (UFBA), Salvador, Bahia, Brazil VI, 111, Pituba, Salvador, BA, Brazil 41810-000 2 Bahian School of Medicine and Public Health, Salvador, Bahia, Brazil (e-mail: [email protected]). Arq Bras Neurocir 2015;34:134 –138. - Abstract Objective To describe axillary approach for axillary nerve transfer with radial nerve branch in brachial plexus lesions. Methods Six patients aged 24 to 54 (mean 30) years with traumatic superior trunk brachial plexus injury underwent axillary approach between October 2011 and April 2012. On physical examination prior to surgery, they could not perform shoulder abduction, external rotation, or elbow flexion. Surgical approach was made through axillary pathway without any muscular section. The transfer was done with the radial branch to the medial head of triceps. In addition to transfer to axillary nerve, each Keywords patient had spinal accessory nerve transferred to suprascapular nerve and ulnar nerve ► axillary nerve fascicle transferred to musculocutaneous nerve. ► brachial plexus Conclusion Theaxillary approach allowseasyaccesstoaxillarynerveand, therefore, is ► transfer a feasible pathway to transferences involving this nerve. Resumo Objetivo Apresentar via axilar por transferência de nervo axilar com ramo de nervo radial em lesões do plexus braquial. Métodos Seis pacientes com idade entre 24 e 54 anos (média de 30) com lesão braquial traumática do plexus no tronco superior submetidos a via axilar entre outubro de 2011 e abril de 2012.