Kinematics Based Physical Modelling and Experimental Analysis of The

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Should Joint Presentation File

6/5/2017 The Shoulder Joint Bones of the shoulder joint • Scapula – Glenoid Fossa Infraspinatus fossa – Supraspinatus fossa Subscapular fossa – Spine Coracoid process – Acromion process • Clavicle • Humerus – Greater tubercle Lesser tubercle – Intertubercular goove Deltoid tuberosity – Head of Humerus Shoulder Joint • Bones: – humerus – scapula Shoulder Girdle – clavicle • Articulation – glenohumeral joint • Glenoid fossa of the scapula (less curved) • head of the humerus • enarthrodial (ball and socket) 1 6/5/2017 Shoulder Joint • Connective tissue – glenoid labrum: cartilaginous ring, surrounds glenoid fossa • increases contact area between head of humerus and glenoid fossa. • increases joint stability – Glenohumeral ligaments: reinforce the glenohumeral joint capsule • superior, middle, inferior (anterior side of joint) – coracohumeral ligament (superior) • Muscles play a crucial role in maintaining glenohumeral joint stability. Movements of the Shoulder Joint • Arm abduction, adduction about the shoulder • Arm flexion, extension • Arm hyperflexion, hyperextension • Arm horizontal adduction (flexion) • Arm horizontal abduction (extension) • Arm external and internal rotation – medial and lateral rotation • Arm circumduction – flexion, abduction, extension, hyperextension, adduction Scapulohumeral rhythm • Shoulder Joint • Shoulder Girdle – abduction – upward rotation – adduction – downward rotation – flexion – elevation/upward rot. – extension – Depression/downward rot. – internal rotation – Abduction (protraction) – external rotation -

Anatomic Variations in Relation to the Origin of the Musculocutaneous Nerve: Absence and Non-Perforation of the Coracobrachialis Muscle

Int. J. Morphol., 36(2):425-429, 2018. Anatomic Variations in Relation to the Origin of the Musculocutaneous Nerve: Absence and Non-Perforation of the Coracobrachialis Muscle. Anatomical Study and Clinical Significance Variaciones Anatómicas en Relación al Origen del Nervio Musculocutáneo: Ausencia y no Perforación del Músculo Coracobraquial: Estudio Anatómico y Significado Clínico Daniel Raúl Ballesteros Larrotta1; Pedro Luis Forero Porras2 & Luis Ernesto Ballesteros Acuña1 BALLESTEROS, D. R.; FORERO, P. L. & BALLESTEROS, L. E. Anatomic variations in relation to the origin of the musculocutaneous nerve: Absence and non-perforation of the coracobrachialis muscle. Anatomical study and clinical significance. Int. J. Morphol., 36(2):425- 429, 2018. SUMMARY: The most frequent anatomic variations of the musculocutaneous nerve could be divided in two main groups: communicating branches with the median nerve and variations in relation to the origin, which in turn can be subdivided into absence of the nerve and non-perforation of the coracobrachialis muscle. Unusual clinical symptoms and/or unusual physical examination in patients with motor disorders, could be explained by anatomic variations of the musculocutaneous nerve. A total of 106 arms were evaluated, corresponding to 53 fresh male cadavers who were undergoing necropsy. The presence or absence of the musculocutaneous nerve was evaluated and whether it pierced the coracobrachialis muscle or not. The lengths of the motor branches and the distances from its origins to the coracoid process were measured. In 10 cases (9.5 %) an unusual origin pattern was observed, of which six (5.7 %) correspond to non-perforation of the coracobrachialis muscle and four (3.8 %) correspond to absence of the nerve. -

Multi-Modal Imaging of the Subscapularis Muscle

Insights Imaging (2016) 7:779–791 DOI 10.1007/s13244-016-0526-1 REVIEW Multi-modal imaging of the subscapularis muscle Mona Alilet1 & Julien Behr2 & Jean-Philippe Nueffer1 & Benoit Barbier-Brion 3 & Sébastien Aubry 1,4 Received: 31 May 2016 /Revised: 6 September 2016 /Accepted: 28 September 2016 /Published online: 17 October 2016 # The Author(s) 2016. This article is published with open access at Springerlink.com Abstract • Long head of biceps tendon medial dislocation can indirect- The subscapularis (SSC) muscle is the most powerful of the ly signify SSC tendon tears. rotator cuff muscles, and plays an important role in shoulder • SSC tendon injury is associated with anterior shoulder motion and stabilization. SSC tendon tear is quite uncom- instability. mon, compared to the supraspinatus (SSP) tendon, and, most • Dynamic ultrasound study of the SSC helps to diagnose of the time, part of a large rupture of the rotator cuff. coracoid impingement. Various complementary imaging techniques can be used to obtain an accurate diagnosis of SSC tendon lesions, as well Keywords Subscapularis . Tendon injury . Rotator cuff . as their extension and muscular impact. Pre-operative diag- Magnetic resonance imaging . Coracoid impingement nosis by imaging is a key issue, since a lesion of the SSC tendon impacts on treatment, surgical approach, and post- operative functional prognosis of rotator cuff injuries. Introduction Radiologists should be aware of the SSC anatomy, variabil- ity in radiological presentation of muscle or tendon injury, The subscapularis (SSC) muscle is one of the four compo- and particular mechanisms that may lead to a SSC injury, nents of the rotator cuff along with the supraspinatus (SSP), such as coracoid impingement. -

M1 – Muscled Arm

M1 – Muscled Arm See diagram on next page 1. tendinous junction 38. brachial artery 2. dorsal interosseous muscles of hand 39. humerus 3. radial nerve 40. lateral epicondyle of humerus 4. radial artery 41. tendon of flexor carpi radialis muscle 5. extensor retinaculum 42. median nerve 6. abductor pollicis brevis muscle 43. flexor retinaculum 7. extensor carpi radialis brevis muscle 44. tendon of palmaris longus muscle 8. extensor carpi radialis longus muscle 45. common palmar digital nerves of 9. brachioradialis muscle median nerve 10. brachialis muscle 46. flexor pollicis brevis muscle 11. deltoid muscle 47. adductor pollicis muscle 12. supraspinatus muscle 48. lumbrical muscles of hand 13. scapular spine 49. tendon of flexor digitorium 14. trapezius muscle superficialis muscle 15. infraspinatus muscle 50. superficial transverse metacarpal 16. latissimus dorsi muscle ligament 17. teres major muscle 51. common palmar digital arteries 18. teres minor muscle 52. digital synovial sheath 19. triangular space 53. tendon of flexor digitorum profundus 20. long head of triceps brachii muscle muscle 21. lateral head of triceps brachii muscle 54. annular part of fibrous tendon 22. tendon of triceps brachii muscle sheaths 23. ulnar nerve 55. proper palmar digital nerves of ulnar 24. anconeus muscle nerve 25. medial epicondyle of humerus 56. cruciform part of fibrous tendon 26. olecranon process of ulna sheaths 27. flexor carpi ulnaris muscle 57. superficial palmar arch 28. extensor digitorum muscle of hand 58. abductor digiti minimi muscle of hand 29. extensor carpi ulnaris muscle 59. opponens digiti minimi muscle of 30. tendon of extensor digitorium muscle hand of hand 60. superficial branch of ulnar nerve 31. -

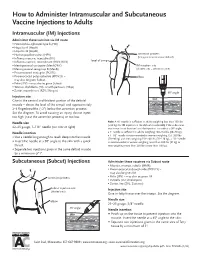

How to Administer Intramuscular and Subcutaneous Vaccines to Adults

How to Administer Intramuscular and Subcutaneous Vaccine Injections to Adults Intramuscular (IM) Injections Administer these vaccines via IM route • Haemophilus influenzae type b (Hib) • Hepatitis A (HepA) • Hepatitis B (HepB) • Human papillomavirus (HPV) acromion process (bony prominence above deltoid) • Influenza vaccine, injectable (IIV) • level of armpit • Influenza vaccine, recombinant (RIV3; RIV4) • Meningococcal conjugate (MenACWY) IM injection site • Meningococcal serogroup B (MenB) (shaded area = deltoid muscle) • Pneumococcal conjugate (PCV13) • Pneumococcal polysaccharide (PPSV23) – elbow may also be given Subcut • Polio (IPV) – may also be given Subcut • Tetanus, diphtheria (Td), or with pertussis (Tdap) • Zoster, recombinant (RZV; Shingrix) 90° angle Injection site skin Give in the central and thickest portion of the deltoid muscle – above the level of the armpit and approximately subcutaneous tissue 2–3 fingerbreadths (~2") below the acromion process. See the diagram. To avoid causing an injury, do not inject muscle too high (near the acromion process) or too low. Needle size Note: A ⅝" needle is sufficient in adults weighing less than 130 lbs (<60 kg) for IM injection in the deltoid muscle only if the subcutane- 22–25 gauge, 1–1½" needle (see note at right) ous tissue is not bunched and the injection is made at a 90° angle; Needle insertion a 1" needle is sufficient in adults weighing 130–152 lbs (60–70 kg); a 1–1½" needle is recommended in women weighing 153–200 lbs • Use a needle long enough to reach deep into the muscle. (70–90 kg) and men weighing 153–260 lbs (70–118 kg); a 1½" needle • Insert the needle at a 90° angle to the skin with a quick is recommended in women weighing more than 200 lbs (91 kg) or thrust. -

MRI Patterns of Shoulder Denervation: a Way to Make It Easy

MRI Patterns Of Shoulder Denervation: A Way To Make It Easy Poster No.: C-2059 Congress: ECR 2018 Type: Educational Exhibit Authors: E. Rossetto1, P. Schvartzman2, V. N. Alarcon2, M. E. Scherer2, D. M. Cecchi3, F. M. Olivera Plata4; 1Buenos Aires, Capital Federal/ AR, 2Buenos Aires/AR, 3Capital Federal, Buenos Aires/AR, 4Ciudad Autonoma de Buenos Aires/AR Keywords: Musculoskeletal joint, Musculoskeletal soft tissue, Neuroradiology peripheral nerve, MR, Education, eLearning, Edema, Inflammation, Education and training DOI: 10.1594/ecr2018/C-2059 Any information contained in this pdf file is automatically generated from digital material submitted to EPOS by third parties in the form of scientific presentations. References to any names, marks, products, or services of third parties or hypertext links to third- party sites or information are provided solely as a convenience to you and do not in any way constitute or imply ECR's endorsement, sponsorship or recommendation of the third party, information, product or service. ECR is not responsible for the content of these pages and does not make any representations regarding the content or accuracy of material in this file. As per copyright regulations, any unauthorised use of the material or parts thereof as well as commercial reproduction or multiple distribution by any traditional or electronically based reproduction/publication method ist strictly prohibited. You agree to defend, indemnify, and hold ECR harmless from and against any and all claims, damages, costs, and expenses, including attorneys' fees, arising from or related to your use of these pages. Please note: Links to movies, ppt slideshows and any other multimedia files are not available in the pdf version of presentations. -

Anatomy, Shoulder and Upper Limb, Shoulder Muscles

Eovaldi BJ, Varacallo M. Anatomy, Shoulder and Upper Limb, Shoulder Muscles. [Updated 2018 Dec 3]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2018 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK534836/ Anatomy, Shoulder and Upper Limb, Shoulder Muscles Authors Benjamin J. Eovaldi1; Matthew Varacallo2. Affilations 1 University of Tennessee HSC 2 Department of Orthopaedic Surgery, University of Kentucky School of Medicine Last Update: December 3, 2018. Introduction The shoulder joint (glenohumeral joint) is a ball and socket joint with the most extensive range of motion in the human body. The muscles of the shoulder dynamically function in performing a wide range of motion, specifically the rotator cuff muscles which function to move the shoulder and arm as well as provide structural integrity to the shoulder joint. The different movements of the shoulder are: abduction, adduction, flexion, extension, internal rotation, and external rotation.[1] The central bony structure of the shoulder is the scapula. All the muscles of the shoulder joint interact with the scapula. At the lateral aspect of the scapula is the articular surface of the glenohumeral joint, the glenoid cavity. The glenoid cavity is peripherally surrounded and reinforced by the glenoid labrum, shoulder joint capsule, supporting ligaments, and the myotendinous attachments of the rotator cuff muscles. The muscles of the shoulder play a critical role in providing stability to the shoulder joint. The primary muscle group that supports the shoulder joint is the rotator cuff muscles. The four rotator cuff muscles include:[2] • Supraspinatus • Infraspinatus • Teres minor • Subscapularis. Structure and Function The upper extremity is attached to the appendicular skeleton by way of the sternoclavicular joint. -

What Causes Infraspinatus Pain and How Can I Treat It?

visited 9/9/2020 9/9/2020 Infraspinatus Pain Causes, Symptoms, and Treatments SUBSCRIBE What Causes Infraspinatus Pain and How Can I Treat It? Medically reviewed by Deborah Weatherspoon, Ph.D., R.N., CRNA — Written by Erica Hersh on January 15, 2020 Causes and symptoms Trigger points and referred pain Diagnosis Treatment Outlook Summary The infraspinatus is one of four muscles that make up the rotator cuff, which helps your arm and shoulder move and stay stable. Your infraspinatus is in the back of your shoulder. It attaches the top of your humerus (the top bone in your arm) to your shoulder, and it helps you rotate your arm to the side. Pain in the infraspinatus is most likely caused by repetitive motion involving the shoulder. Swimmers, tennis players, painters, and carpenters get it more frequently. It also becomes more likely as you get older. There are several potential causes of infraspinatus pain. Some are serious, but none are life threatening. ADVERTISEMENT ADVERTISEMENT Infraspinatus muscle pain causes https://www.healthline.com/health/infraspinatus-pain 1/15 visited 9/9/2020 9/9/2020 Infraspinatus Pain Causes, Symptoms, and Treatments Sometimes, infraspinatus pain is due to minor strains or wear and tear. In these cases, rest will likely relieve the pain. But your pain may also be caused by an injury or more serious conditions. Infraspinatus tear There are two types of infraspinatus tears: A partial tear will damage the tendon, but it doesn’t go all the way through. It’s usually caused by repetitive stress or normal aging. A complete, or full-thickness, tear severs the infraspinatus from the bone. -

Arterial Supply to the Rotator Cuff Muscles

Int. J. Morphol., 32(1):136-140, 2014. Arterial Supply to the Rotator Cuff Muscles Suministro Arterial de los Músculos del Manguito Rotador N. Naidoo*; L. Lazarus*; B. Z. De Gama*; N. O. Ajayi* & K. S. Satyapal* NAIDOO, N.; LAZARUS, L.; DE GAMA, B. Z.; AJAYI, N. O. & SATYAPAL, K. S. Arterial supply to the rotator cuff muscles.Int. J. Morphol., 32(1):136-140, 2014. SUMMARY: The arterial supply to the rotator cuff muscles is generally provided by the subscapular, circumflex scapular, posterior circumflex humeral and suprascapular arteries. This study involved the bilateral dissection of the scapulohumeral region of 31 adult and 19 fetal cadaveric specimens. The subscapularis muscle was supplied by the subscapular, suprascapular and circumflex scapular arteries. The supraspinatus and infraspinatus muscles were supplied by the suprascapular artery. The infraspinatus and teres minor muscles were found to be supplied by the circumflex scapular artery. In addition to the branches of these parent arteries, the rotator cuff muscles were found to be supplied by the dorsal scapular, lateral thoracic, thoracodorsal and posterior circumflex humeral arteries. The variations in the arterial supply to the rotator cuff muscles recorded in this study are unique and were not described in the literature reviewed. Due to the increased frequency of operative procedures in the scapulohumeral region, the knowledge of variations in the arterial supply to the rotator cuff muscles may be of practical importance to surgeons and radiologists. KEY WORDS: Arterial supply; Variations; Rotator cuff muscles; Parent arteries. INTRODUCTION (Abrassart et al.). In addition, the muscular parts of infraspinatus and teres minor muscles were supplied by the circumflex scapular artery while the tendinous parts of these The rotator cuff is a musculotendionous cuff formed muscles received branches from the posterior circumflex by the fusion of the tendons of four muscles – viz. -

Electrodiagnosis of Brachial Plexopathies and Proximal Upper Extremity Neuropathies

Electrodiagnosis of Brachial Plexopathies and Proximal Upper Extremity Neuropathies Zachary Simmons, MD* KEYWORDS Brachial plexus Brachial plexopathy Axillary nerve Musculocutaneous nerve Suprascapular nerve Nerve conduction studies Electromyography KEY POINTS The brachial plexus provides all motor and sensory innervation of the upper extremity. The plexus is usually derived from the C5 through T1 anterior primary rami, which divide in various ways to form the upper, middle, and lower trunks; the lateral, posterior, and medial cords; and multiple terminal branches. Traction is the most common cause of brachial plexopathy, although compression, lacer- ations, ischemia, neoplasms, radiation, thoracic outlet syndrome, and neuralgic amyotro- phy may all produce brachial plexus lesions. Upper extremity mononeuropathies affecting the musculocutaneous, axillary, and supra- scapular motor nerves and the medial and lateral antebrachial cutaneous sensory nerves often occur in the context of more widespread brachial plexus damage, often from trauma or neuralgic amyotrophy but may occur in isolation. Extensive electrodiagnostic testing often is needed to properly localize lesions of the brachial plexus, frequently requiring testing of sensory nerves, which are not commonly used in the assessment of other types of lesions. INTRODUCTION Few anatomic structures are as daunting to medical students, residents, and prac- ticing physicians as the brachial plexus. Yet, detailed understanding of brachial plexus anatomy is central to electrodiagnosis because of the plexus’ role in supplying all motor and sensory innervation of the upper extremity and shoulder girdle. There also are several proximal upper extremity nerves, derived from the brachial plexus, Conflicts of Interest: None. Neuromuscular Program and ALS Center, Penn State Hershey Medical Center, Penn State College of Medicine, PA, USA * Department of Neurology, Penn State Hershey Medical Center, EC 037 30 Hope Drive, PO Box 859, Hershey, PA 17033. -

Coracobrachialis Muscle Pierced by Two Nerves: Case Report

Case Report www.anatomy.org.tr Received: April 6, 2016; Accepted: June 13, 2016 doi:10.2399/ana.16.008 Coracobrachialis muscle pierced by two nerves: case report Dawit Habte Woldeyes, Belta Asnakew Abegaz Department of Human Anatomy, College of Medicine and Health Sciences, Bahir Dar University, Bahir Dar, Ethiopia Abstract The brachial plexus is formed by the union of the ventral rami of C5–T1. Contributions to the plexus by C4 and T2 differ. The coracobrachialis muscle is an elongated muscle in the superomedial part of the arm. It is a useful landmark for locating other structures in the arm. Variations exist to the coracobrachialis muscle, and to the formation of the brachial plexus, its terminal branches and its relation to surrounding structures. In this report, the coracobrachialis muscle is pierced by two nerves, and one of these nerves joins the median nerve after piercing the coracobrachialis muscle. Awareness of the possible variations of brachial plexus and its surrounding structures is necessary for adequate clinical, surgical and radiological management. Keywords: brachial plexus; coracobrachialis; median nerve; musculocutaneous nerve; unnamed nerve Anatomy 2016;10(2):148–152 ©2016 Turkish Society of Anatomy and Clinical Anatomy (TSACA) Introduction locating other structures in the arm; i.e., the musculocu- taneous nerve pierces it, and the distal part of its attach- The brachial plexus is formed by the union of the ventral ment indicates the location of the nutrient foramen of rami of C5–T1. The most common arrangement of the the humerus.[6,7] brachial plexus is as follows: the fifth and sixth rami unite as the upper trunk, the eighth cervical and first thoracic Variations in the formation of the brachial plexus and its terminal branches in the upper extremity are rami join as the lower trunk, the seventh cervical ramus [1] becomes the middle trunk. -

Changes in Infraspinatus Cross-Sectional Area and Echo Intensity in Relation to Scapular Dyskinesis and Overhead Training Volume in Collegiate Volleyball Players

CHANGES IN INFRASPINATUS CROSS-SECTIONAL AREA AND ECHO INTENSITY IN RELATION TO SCAPULAR DYSKINESIS AND OVERHEAD TRAINING VOLUME IN COLLEGIATE VOLLEYBALL PLAYERS Kimberly Chase A thesis submitted to the faculty at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Masters of Arts in the Department of Exercise & Sport Science (Athletic Training) in the College of Arts & Sciences. Chapel Hill 2016 Approved by: D. Padua T. Blackburn L. Stanley i © 2016 Kimberly Chase ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii ABSTRACT Kimberly Chase: Changes in Infraspinatus Cross-Sectional Area and Echo Intensity in Relation to Scapular Dyskinesis and Overhead Training Volume in Collegiate Volleyball Players (Under the Direction of Darin Padua) During the pre-season injury risk in volleyball is highest at 6.1 injuries/1000 exposures. Injury to the posterior shoulder, specifically the infraspinatus, has been attributed to repetitive eccentric loading. The high volume of overhead activity in the collegiate volleyball player has been identified is a risk factor for upper extremity injury. Cross sectional area and echo intensity of the infraspinatus muscle were assessed using diagnostic ultrasound to measure muscle damage. Visual observation of scapular dyskinesis was completed at baseline and 24 hours following the pre-season training period to assess changes due to pre-season training volume. Correlations between cross sectional area, echo intensity, scapular dyskinesis, and swing count were also examined to assess relationships between these variables. Acceptable reliability was established for all measurements. This study found no significant outcomes in cross sectional area or echo intensity, in the severity of scapular dyskinesis, or in relationships between the variables of interest.