Electrodiagnosis of Brachial Plexopathies and Proximal Upper Extremity Neuropathies

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Redalyc.Variations in Branching Pattern of the Axillary Artery: a Study

Jornal Vascular Brasileiro ISSN: 1677-5449 [email protected] Sociedade Brasileira de Angiologia e de Cirurgia Vascular Brasil Astik, Rajesh; Dave, Urvi Variations in branching pattern of the axillary artery: a study in 40 human cadavers Jornal Vascular Brasileiro, vol. 11, núm. 1, marzo, 2012, pp. 12-17 Sociedade Brasileira de Angiologia e de Cirurgia Vascular São Paulo, Brasil Available in: http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=245023701001 How to cite Complete issue Scientific Information System More information about this article Network of Scientific Journals from Latin America, the Caribbean, Spain and Portugal Journal's homepage in redalyc.org Non-profit academic project, developed under the open access initiative ORIGINAL ARTICLE Variations in branching pattern of the axillary artery: a study in 40 human cadavers Variações na ramificação do padrão da artéria axilar: um estudo em 40 cadáveres humanos Rajesh Astik1, Urvi Dave2 Abstract Background: Variations in the branching pattern of the axillary artery are a rule rather than an exception. The knowledge of these variations is of anatomical, radiological, and surgical interest to explain unexpected clinical signs and symptoms. Objective: The large percentage of variations in branching pattern of axillary artery is making it worthwhile to take any anomaly into consideration. The type and frequency of these vascular variations should be well understood and documented, as increasing performance of coronary artery bypass surgery and other cardiovascular surgical procedures. The objective of this study is to observe variations in axillary artery branches in human cadavers. Methods: We dissected 80 limbs of 40 human adult embalmed cadavers of Asian origin and we have studied the branching patterns of the axillary artery. -

Anatomical Variations of the Brachial Plexus Terminal Branches in Ethiopian Cadavers

ORIGINAL COMMUNICATION Anatomy Journal of Africa. 2017. Vol 6 (1): 896 – 905. ANATOMICAL VARIATIONS OF THE BRACHIAL PLEXUS TERMINAL BRANCHES IN ETHIOPIAN CADAVERS Edengenet Guday Demis*, Asegedeche Bekele* Corresponding Author: Edengenet Guday Demis, 196, University of Gondar, Gondar, Ethiopia. Email: [email protected] ABSTRACT Anatomical variations are clinically significant, but many are inadequately described or quantified. Variations in anatomy of the brachial plexus are important to surgeons and anesthesiologists performing surgical procedures in the neck, axilla and upper limb regions. It is also important for radiologists who interpret plain and computerized imaging and anatomists to teach anatomy. This study aimed to describe the anatomical variations of the terminal branches of brachial plexus on 20 Ethiopian cadavers. The cadavers were examined bilaterally for the terminal branches of brachial plexus. From the 40 sides studied for the terminal branches of the brachial plexus; 28 sides were found without variation, 10 sides were found with median nerve variation, 2 sides were found with musculocutaneous nerve variation and 2 sides were found with axillary nerve variation. We conclude that variation in the median nerve was more common than variations in other terminal branches. Key words: INTRODUCTION The brachial plexus is usually formed by the may occur (Moore and Dalley, 1992, Standring fusion of the anterior primary rami of the C5-8 et al., 2005). and T1 spinal nerves. It supplies the muscles of the back and the upper limb. The C5 and C6 fuse Most nerves in the upper limb arise from the to form the upper trunk, the C7 continues as the brachial plexus; it begins in the neck and extends middle trunk and the C8 and T1 join to form the into the axilla. -

Brachial-Plexopathy.Pdf

Brachial Plexopathy, an overview Learning Objectives: The brachial plexus is the network of nerves that originate from cervical and upper thoracic nerve roots and eventually terminate as the named nerves that innervate the muscles and skin of the arm. Brachial plexopathies are not common in most practices, but a detailed knowledge of this plexus is important for distinguishing between brachial plexopathies, radiculopathies and mononeuropathies. It is impossible to write a paper on brachial plexopathies without addressing cervical radiculopathies and root avulsions as well. In this paper will review brachial plexus anatomy, clinical features of brachial plexopathies, differential diagnosis, specific nerve conduction techniques, appropriate protocols and case studies. The reader will gain insight to this uncommon nerve problem as well as the importance of the nerve conduction studies used to confirm the diagnosis of plexopathies. Anatomy of the Brachial Plexus: To assess the brachial plexus by localizing the lesion at the correct level, as well as the severity of the injury requires knowledge of the anatomy. An injury involves any condition that impairs the function of the brachial plexus. The plexus is derived of five roots, three trunks, two divisions, three cords, and five branches/nerves. Spinal roots join to form the spinal nerve. There are dorsal and ventral roots that emerge and carry motor and sensory fibers. Motor (efferent) carries messages from the brain and spinal cord to the peripheral nerves. This Dorsal Root Sensory (afferent) carries messages from the peripheral to the Ganglion is why spinal cord or both. A small ganglion containing cell bodies of sensory NCS’s sensory fibers lies on each posterior root. -

Study of Brachial Plexus with Regards to Its Formation, Branching Pattern and Variations and Possible Clinical Implications of Those Variations

IOSR Journal of Dental and Medical Sciences (IOSR-JDMS) e-ISSN: 2279-0853, p-ISSN: 2279-0861.Volume 15, Issue 4 Ver. VII (Apr. 2016), PP 23-28 www.iosrjournals.org Study of Brachial Plexus With Regards To Its Formation, Branching Pattern and Variations and Possible Clinical Implications of Those Variations. Dr. Shambhu Prasad1, Dr. Pankaj K Patel2 1 (Assistant Professor , Department of Anatomy , NMCH , Sasaram , India ) 2 (Assistant Professor , Department of Pathology , NMCH , Sasaram , India ) Abstract: Aim of the study: to search variations in formation and branching pattern of brachial plexus and correlate them with possible clinical and surgical implications. Materials and Methods: 25human bodies were dissected for this study. Dissection was started in posterior triangle of neck and extended to distal part of upper limb passing through axilla . Photographs were taken and data was tabulated and analyzed . Observations: All 50 plexuses had origin from C5 – T1 . Dorsal scapular nerve was absent in 2 plexuses. Long thoracic nerve was made of C5,C6 fibers in one and of C6,C7 fibers in another . Lower trunk was abnormal in 2 plexuses both of same body, their was no contribution from T1 fibers to posterior cord in one of these plexus. One plexus had double lateral pectoral nerve , communication between lateral and medial pectoral nerves , lateral pectoral and medial root of median nerve also between musculocutaneous and lateral root of median nerve . 2 more plexuses had communication between lateral and medial pectoral nerves. One plexus showed 2 branches coming from posterior division of upper trunk itself before formation of posterior cord. -

Anatomical Study of the Brachial Plexus in Human Fetuses and Its Relation with Neonatal Upper Limb Paralysis

ORIGINAL ARTICLE Anatomical study of the brachial plexus Official Publication of the Instituto Israelita de Ensino e Pesquisa Albert Einstein in human fetuses and its relation with neonatal upper limb paralysis ISSN: 1679-4508 | e-ISSN: 2317-6385 Estudo anatômico do plexo braquial de fetos humanos e sua relação com paralisias neonatais do membro superior Marcelo Rodrigues da Cunha1, Amanda Aparecida Magnusson Dias1, Jacqueline Mendes de Brito2, Cristiane da Silva Cruz1, Samantha Ketelyn Silva1 1 Faculdade de Medicina de Jundiaí, Jundiaí, SP, Brazil. 2 Centro Universitário Padre Anchieta, Jundiaí, SP, Brazil. DOI: 10.31744/einstein_journal/2020AO5051 ❚ ABSTRACT Objective: To study the anatomy of the brachial plexus in fetuses and to evaluate differences in morphology during evolution, or to find anatomical situations that can be identified as the cause of obstetric paralysis. Methods: Nine fetuses (12 to 30 weeks of gestation) stored in formalin were used. The supraclavicular and infraclavicular parts of the brachial plexus were dissected. Results: In its early course, the brachial plexus had a cord-like shape when it passed through the scalene hiatus. Origin of the phrenic nerve in the brachial plexus was observed in only one fetus. In the deep infraclavicular and retropectoralis minor spaces, the nerve fibers of the brachial plexus were distributed in the axilla and medial bicipital groove, where they formed the nerve endings. Conclusion: The brachial plexus of human fetuses presents variations and relations with anatomical structures that must be considered during clinical and surgical procedures for neonatal paralysis of the upper limbs. How to cite this article: Cunha MR, Dias AA, Brito JM, Cruz CS, Silva Keywords: Brachial plexus/anatomy & histology; Fetus/abnormalities; Paralysis SK. -

Bilateral Presence of a Variant Subscapularis Muscle

CASE REPORT Bilateral presence of a variant subscapularis muscle Krause DA and Youdas JW Krause DA, Youdas JW. Bilateral presence of a variant subscapularis the lateral subscapularis inserting into the proximal humerus with the tendon of muscle. Int J Anat Var. 2017;10(4):79-80. the subscapularis. The axillary and lower subscapular nerves coursed between the observed muscle and the subscapularis. The presence of the muscle has potential ABSTRACT to entrap the axillary nerve and the lower subscapular nerve. We describe the presence of an accessory subscapularis muscle observed bilaterally Key Words: Accessory subscapularis; Axillary nerve; Lower subscapular nerve; in a human anatomy laboratory. The muscle originated from the mid-region of Entrapment INTRODUCTION everal anatomic variations in axillary musculature have been reported (1- S4). One of the more common variations is the axillary arch muscle, also known as Langer’s muscle, the axillopectoral muscle, and the pectordorsal muscle (3,4). This muscle typically arises from the lateral aspect of the latissimus dorsi inserting deep to the pectoralis major on the humerus. Several variations of the axillary arch muscle are described with a reported incidence of 6-9% (4-6). Less frequent and distinctly different than the axillary arch muscle, is a variant muscle associated with the subscapularis. This has been termed the subscapulo-humeral muscle, subscapularis minor, subscapularis-teres-latissimus muscle, and the accessory subcapularis muscle (1,2,7). Reported incidence ranges from 0.45 to 2.6% (2,7). CASE REPORT A variant muscle associated with the subscapularis bilaterally was observed on a Caucasian female embalmed cadaver during routine dissection in a human anatomy class for first year physical therapy students. -

Risk of Encountering Dorsal Scapular and Long Thoracic Nerves During Ultrasound-Guided Interscalene Brachial Plexus Block with Nerve Stimulator

Korean J Pain 2016 July; Vol. 29, No. 3: 179-184 pISSN 2005-9159 eISSN 2093-0569 http://dx.doi.org/10.3344/kjp.2016.29.3.179 | Original Article | Risk of Encountering Dorsal Scapular and Long Thoracic Nerves during Ultrasound-guided Interscalene Brachial Plexus Block with Nerve Stimulator Department of Anesthesiology and Pain Medicine, Wonkwang University College of Medicine, Wonkwang Institute of Science, Iksan, *Department of Anesthesiology and Pain Medicine, Presbyterian Medical Center, University of Seonam College of Medicine, Jeonju, Korea Yeon Dong Kim, Jae Yong Yu*, Junho Shim*, Hyun Joo Heo*, and Hyungtae Kim* Background: Recently, ultrasound has been commonly used. Ultrasound-guided interscalene brachial plexus block (IBPB) by posterior approach is more commonly used because anterior approach has been reported to have the risk of phrenic nerve injury. However, posterior approach also has the risk of causing nerve injury because there are risks of encountering dorsal scapular nerve (DSN) and long thoracic nerve (LTN). Therefore, the aim of this study was to evaluate the risk of encountering DSN and LTN during ultrasound-guided IBPB by posterior approach. Methods: A total of 70 patients who were scheduled for shoulder surgery were enrolled in this study. After deciding insertion site with ultrasound, awake ultrasound-guided IBPB with nerve stimulator by posterior approach was performed. Incidence of muscle twitches (rhomboids, levator scapulae, and serratus anterior muscles) and current intensity immediately before muscle twitches disappeared were recorded. Results: Of the total 70 cases, DSN was encountered in 44 cases (62.8%) and LTN was encountered in 15 cases (21.4%). Both nerves were encountered in 10 cases (14.3%). -

Bilateral Anatomical Variation in the Formation of Trunks of the Brachial Plexus - a Case Report

THIEME Case Report 9 Bilateral Anatomical Variation in the Formation of Trunks of the Brachial Plexus - A Case Report E.F. Lasch1 M.B. Nazer1 L.M. Bartholdy1 1 Laboratório de Anatomia Humana, Departamento de Biologia e Address for correspondence E. F. Lasch, Laboratório de Anatomia Farmácia, Universidade Santa Cruz do Sul – UNISC, Santa Cruz do Sul, Humana, Departamento de Biologia e Farmácia, Universidade Santa RioGrandedoSul,Brazil Cruz do Sul – UNISC, Av Independência, 2293, CEP 96815-900, Santa Cruz do Sul, RS, Brazil (e-mail: [email protected]). J Morphol Sci 2018;35:9–13. Abstract This study presents a bilateral variation in the formation of trunks of brachial plexus in a male cadaver. The right brachial plexus was composed of six roots (C4-T1) and the left brachial plexus of five roots (C5-T1). Both formed four trunks thus changing the contributions of the anterior divisions of the cervical nerves involved in the formation Keywords of the cords and the five main somatic motor nerves for the upper limb. There are very ► brachial plexus few case reports in the scientific literature on this topic; thus making the present study ► trunks very relevant. Introduction medial and lateral pectoral nerve, arise from the cords and innervate the shoulder muscles. The long infraclavicular Most of the upper limb nerves arise from by the brachial branches, which extend longitudinally to the upper limb, plexus (BP), which has a complex anatomical structure that are: the radial nerve, the ulnar nerve, and the median begins in the root of the neck and extends to the axilla nerve.4,5 (armpit region). -

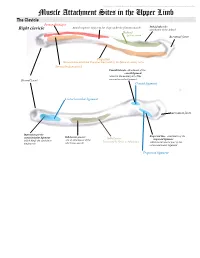

Muscle Attachment Sites in the Upper Limb

This document was created by Alex Yartsev ([email protected]); if I have used your data or images and forgot to reference you, please email me. Muscle Attachment Sites in the Upper Limb The Clavicle Pectoralis major Smooth superior surface of the shaft, under the platysma muscle Deltoid tubercle: Right clavicle attachment of the deltoid Deltoid Axillary nerve Acromial facet Trapezius Sternocleidomastoid and Trapezius innervated by the Spinal Accessory nerve Sternocleidomastoid Conoid tubercle, attachment of the conoid ligament which is the medial part of the Sternal facet coracoclavicular ligament Conoid ligament Costoclavicular ligament Acromial facet Impression for the Trapezoid line, attachment of the costoclavicular ligament Subclavian groove: Subclavius trapezoid ligament which binds the clavicle to site of attachment of the Innervated by Nerve to Subclavius which is the lateral part of the the first rib subclavius muscle coracoclavicular ligament Trapezoid ligament This document was created by Alex Yartsev ([email protected]); if I have used your data or images and forgot to reference you, please email me. The Scapula Trapezius Right scapula: posterior Levator scapulae Supraspinatus Deltoid Deltoid and Teres Minor are innervated by the Axillary nerve Rhomboid minor Levator Scapulae, Rhomboid minor and Rhomboid Major are innervated by the Dorsal Scapular Nerve Supraspinatus and Infraspinatus innervated by the Suprascapular nerve Infraspinatus Long head of triceps Rhomboid major Teres Minor Teres Major Teres Major -

Anatomical, Clinical, and Electrodiagnostic Features of Radial Neuropathies

Anatomical, Clinical, and Electrodiagnostic Features of Radial Neuropathies a, b Leo H. Wang, MD, PhD *, Michael D. Weiss, MD KEYWORDS Radial Posterior interosseous Neuropathy Electrodiagnostic study KEY POINTS The radial nerve subserves the extensor compartment of the arm. Radial nerve lesions are common because of the length and winding course of the nerve. The radial nerve is in direct contact with bone at the midpoint and distal third of the humerus, and therefore most vulnerable to compression or contusion from fractures. Electrodiagnostic studies are useful to localize and characterize the injury as axonal or demyelinating. Radial neuropathies at the midhumeral shaft tend to have good prognosis. INTRODUCTION The radial nerve is the principal nerve in the upper extremity that subserves the extensor compartments of the arm. It has a long and winding course rendering it vulnerable to injury. Radial neuropathies are commonly a consequence of acute trau- matic injury and only rarely caused by entrapment in the absence of such an injury. This article reviews the anatomy of the radial nerve, common sites of injury and their presentation, and the electrodiagnostic approach to localizing the lesion. ANATOMY OF THE RADIAL NERVE Course of the Radial Nerve The radial nerve subserves the extensors of the arms and fingers and the sensory nerves of the extensor surface of the arm.1–3 Because it serves the sensory and motor Disclosures: Dr Wang has no relevant disclosures. Dr Weiss is a consultant for CSL-Behring and a speaker for Grifols Inc. and Walgreens. He has research support from the Northeast ALS Consortium and ALS Therapy Alliance. -

Examination of the Shoulder Bruce S

Examination of the Shoulder Bruce S. Wolock, MD Towson Orthopaedic Associates 3 Joints, 1 Articulation 1. Sternoclavicular 2. Acromioclavicular 3. Glenohumeral 4. Scapulothoracic AC Separation Bony Landmarks 1. Suprasternal notch 2. Sternoclavicular joint 3. Coracoid 4. Acromioclavicular joint 5. Acromion 6. Greater tuberosity of the humerus 7. Bicipital groove 8. Scapular spine 9. Scapular borders-vertebral and lateral Sternoclavicular Dislocation Soft Tissues 1. Rotator Cuff 2. Subacromial bursa 3. Axilla 4. Muscles: a. Sternocleidomastoid b. Pectoralis major c. Biceps d. Deltoid Congenital Absence of Pectoralis Major Pectoralis Major Rupture Soft Tissues (con’t) e. Trapezius f. Rhomboid major and minor g. Latissimus dorsi h. Serratus anterior Range of Motion: Active and Passive 1. Abduction - 90 degrees 2. Adduction - 45 degrees 3. Extension - 45 degrees 4. Flexion - 180 degrees 5. Internal rotation – 90 degrees 6. External rotation – 45 degrees Muscle Testing 1. Flexion a. Primary - Anterior deltoid (axillary nerve, C5) - Coracobrachialis (musculocutaneous nerve, C5/6 b. Secondary - Pectoralis major - Biceps Biceps Rupture- Longhead Muscle Testing 2. Extension a. Primary - Latissimus dorsi (thoracodorsal nerve, C6/8) - Teres major (lower subscapular nerve, C5/6) - Posterior deltoid (axillary nerve, C5/6) b. Secondary - Teres minor - Triceps Abduction Primary a. Middle deltoid (axillary nerve, C5/6) b. Supraspinatus (suprascapular nerve, C5/6) Secondary a. Anterior and posterior deltoid b. Serratus anterior Deltoid Ruputure Axillary Nerve Palsy Adduction Primary a. Pectoralis major (medial and lateral pectoral nerves, C5-T1 b. Latissimus dorsi (thoracodorsal nerve, C6/8) Secondary a. Teres major b. Anterior deltoid External Rotation Primary a. Infraspinatus (suprascapular nerve, C5/6) b. Teres minor (axillary nerve, C5) Secondary a. -

Chapter 30 When It Is Not Cervical Radiculopathy: Thoracic Outlet Syndrome—A Prospective Study on Diagnosis and Treatment

Chapter 30 When it is Not Cervical Radiculopathy: Thoracic Outlet Syndrome—A Prospective Study on Diagnosis and Treatment J. Paul Muizelaar, M.D., Ph.D., and Marike Zwienenberg-Lee, M.D. Many neurosurgeons see a large number of patients with some type of discomfort in the head, neck, shoulder, arm, or hand, most of which are (presumably) cervical disc problems. When there is good agreement between the history, physical findings, and imaging (MRI in particular), the diagnosis of cervical disc disease is easily made. When this agreement is less than ideal, we usually get an electromyography (EMG), which in many cases is sufficient to confirm cervical radiculopathy or establish another diagnosis. However, when an EMG does not provide too many clues as to the cause of the discomfort, serious consideration must be given to other painful syndromes such as thoracic outlet syndrome (TOS) and some of its variants, occipital or C2 neuralgia, tumors of or affecting the brachial plexus, and orthopedic problems of the shoulder (Table 30.1). Of these, TOS is the most controversial and difficult to diagnose. Although the neurosurgeons Adson (1–3) and Naffziger (10,11) are well represented as pioneers in the literature on TOS, this condition has received only limited attention in neurosurgical circles. In fact, no original publication in NEUROSURGERY or the Journal of Neurosurgery has addressed the issue of TOS, except for an overview article in NEUROSURGERY (12). At the time of writing of this paper, two additional articles have appeared in Neurosurgery: one general review article and another strictly surgical series comprising 33 patients with a Gilliatt-Sumner hand (7).