Arboreal Ants Use the ”Velcro(R) Principle” to Capture Very Large Prey

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

FIELD OBSERVATIONS of TROPIDACRIS COLLARIS (ORTHOPTERA: ROMALEIDAE) Christopher K

FIELD OBSERVATIONS OF TROPIDACRIS COLLARIS (ORTHOPTERA: ROMALEIDAE) Christopher K. Starr Dep't of Life Sciences, University of the West Indies,St Augustine, Trinidad & 'Ibbago cstarr{jj}centre.uwi.tt Tropidacris i s a neotropi c al genus of three known s peci es aggregation close to the ground on a small shrub c lose along that include the largest g r asshoppers in the world (Carbone ll side the gulch. I netted a sampl e of these, which disturbance 19 86). Two species, T. collaris and T. crisrata, have very caused the remai nin g individuals to scatter. Some time later broad ranges that include mos t of South America north of the I returned to that spot and found th e aggregation re-formed southern cone . The former is the species found on Margarita in a s imilar s ituation less than a meter from where I had first Is land, wh il e the range of the latter inc ludes Tri nidad and found it. Although I did not attempt to quantify ad ult densi Tobago. The two are readily distingui s hed by the fo llowing ty in any part of the gulch, they appeared to be most concen adult characters (Carbonell 1984.1986): a) a nte nnae enti rely trated within a very few meters of the aggregation of hoppers. yellow in T. collaris, basal two segments brown to black in T. I tas ted one hopper and found it to be very biller. approx cristata, b) dorsa l crest of pronotum continu ing o nto posteri imately like an adu lt mo narch butterfly (Danaus plexippus). -

Spreading of Heterochromatin and Karyotype Differentiation in Two Tropidacris Scudder, 1869 Species (Orthoptera, Romaleidae)

COMPARATIVE A peer-reviewed open-access journal CompCytogen 9(3): 435–450 (2015)Spreading of heterochromatin in Tropidacris 435 doi: 10.3897/CompCytogen.v9i3.5160 RESEARCH ARTICLE Cytogenetics http://compcytogen.pensoft.net International Journal of Plant & Animal Cytogenetics, Karyosystematics, and Molecular Systematics Spreading of heterochromatin and karyotype differentiation in two Tropidacris Scudder, 1869 species (Orthoptera, Romaleidae) Marília de França Rocha1, Mariana Bozina Pine2, Elizabeth Felipe Alves dos Santos Oliveira3, Vilma Loreto3, Raquel Bozini Gallo2, Carlos Roberto Maximiano da Silva2, Fernando Campos de Domenico4, Renata da Rosa2 1 Departamento de Biologia, ICB, Universidade de Pernambuco, Recife, Pernambuco, Brazil 2 Departamento de Biologia Geral, CCB, Universidade Estadual de Londrina (UEL), Londrina, Paraná, Brazil 3 Depar- tamento de Genética, CCB, Universidade Federal de Pernambuco, Recife, Pernambuco, Brazil 4 Museu de Zoologia, Instituto de Biociência, Universidade de São Paulo, São Paulo, São Paulo, Brazil Corresponding author: Renata da Rosa ([email protected]) Academic editor: V. Gokhman | Received 22 April 2015 | Accepted 5 June 2015 | Published 24 July 2015 http://zoobank.org/12E31847-E92E-41AA-8828-6D76A3CFF70D Citation: Rocha MF, Pine MB, dos Santos Oliveira EFA, Loreto V, Gallo RB, da Silva CRM, de Domenico FC, da Rosa R (2015) Spreading of heterochromatin and karyotype differentiation in twoTropidacris Scudder, 1869 species (Orthoptera, Romaleidae). Comparative Cytogenetics 9(3): 435–450. doi: 10.3897/CompCytogen.v9i3.5160 Abstract Tropidacris Scudder, 1869 is a genus widely distributed throughout the Neotropical region where specia- tion was probably promoted by forest reduction during the glacial and interglacial periods. There are no cytogenetic studies of Tropidacris, and information allowing inference or confirmation of the evolutionary events involved in speciation within the group is insufficient. -

Descrição Histológica Do Estomedeu De Tropidacris Collaris (Stoll, 1813) (Orthoptera: Romaleidae)

Descrição histológica do estomedeu de Tropidacris collaris (Stoll, 1813) (Orthoptera: Romaleidae). 259 DESCRIÇÃO HISTOLÓGICA DO ESTOMEDEU DE TROPIDACRIS COLLARIS (STOLL, 1813) (ORTHOPTERA: ROMALEIDAE) M.K.C.M. Costa1, F.D. Santos1*, A.V.S. Ferreira1*, V.W. Teixeira2**, A.A.C. Teixeira2 1Departamento de Morfologia e Fisiologia Animal, Universidade Federal Rural de Pernambuco, Rua Dom Manoel de Medeiros, s/no, CEP 52171-900, Recife, PE, Brasil. E-mail: [email protected] RESUMO A presente pesquisa foi desenvolvida no Laboratório de Histologia do Departamento de Morfologia e Fisiologia Animal da Universidade Federal Rural de Pernambuco (UFRPE), Recife, tendo como objetivo descrever a histologia do estomodeu (faringe, esôfago, inglúvio e proventrículo), de Tropidacris collaris (Stoll, 1813) (Orthoptera: Romaleidae), por meio da microscopia de luz, utilizando-se colorações especiais (Tricrômico de Mallory, Tricrômico de Gomori e P.A.S. – Ácido periódico de Schiff) e de rotina (Hematoxilina-Eosina). Os insetos foram obtidos da criação existente no Laboratório de Entomologia, do Departamento de Biologia, da UFRPE. O material coletado foi fixado em Boüin alcoólico e processado para inclusão em "paralast". Os resultados mostraram que os órgãos do estomodeu apresentam-se constituídos por tecido epitelial simples, recoberto por uma íntima contendo espículas, exceto no proventrículo, e tecido muscular estriado envolvendo esses órgãos. No proventrículo a camada epitelial se projeta para a luz formando 12 dobras maiores intercaladas por dobras menores. Não foi evidenciada a presença de tecido conjuntivo nos órgãos do estomodeu. PALAVRAS-CHAVE: Orthoptera, morfologia, estomodeu, Tropidacris collaris. ABSTRACT HISTOLOGIC DESCRIPTION OF THE FOREGUT OF TROPIDACRIS COLLARIS (STOLL, 1813) (ORTHOPTERA: ROMALEIDAE). The present research was developed in the Laboratorio de Histologia do Departamento de Morfologia e Fisiologia Animal da Universidade Federal Rural de Pernambuco (UFRPE), Recife. -

Cordyceps Locustiphila (Hypocreales: Cordycipitaceae) Infecting the Grasshopper Pest Tropidacris Collaris (Orthoptera: Acridoidea: Romaleidae)

Nova Hedwigia Vol. 107 (2018) Issue 3–4, 349–356 Article Cpublished online February 6, 2018; published in print November 2018 Cordyceps locustiphila (Hypocreales: Cordycipitaceae) infecting the grasshopper pest Tropidacris collaris (Orthoptera: Acridoidea: Romaleidae) Sebastian A. Pelizza1,2*, María C.Scattolini1, Cristian Bardi1, Carlos E. Lange1,4, Sebastian A. Stenglein3 and Marta N. Cabello2,4 1 Centro de Estudios Parasitológicos y de Vectores (CEPAVE), CCT La Plata-CONICET- UNLP, Boulevard 120 s/n entre Av. 60 y Calle 64, La Plata (1900), Argentina 2 Instituto de Botánica Carlos Spegazzini (FCNyM-UNLP), Calle 53 # 477, La Plata (1900), Argentina 3 Laboratorio de Biología Funcional y Biotecnología (BIOLAB)-CICBA-INBIOTEC, Facultad de Agronomía de Azul, UNCPBA, Republica de Italia # 780, Azul (7300), Argentina 4 Comisión de Investigaciones Científicas de la Provincia de BuenosAires (CICPBA) With 3 figures Abstract: Cordyceps locustiphila is described, illustrated, and compared with a previous finding. This species was collected infecting Tropidacris collaris in the Yabotí biosphere reserve, Misiones province, Argentina. Until now, this entomopathogenic fungus has not been reported affecting T. collaris, and it is the first report for Argentina. From the cordyceps-like stromata of C. locustiphila it was possible to isolate for the first time the acremonium-like anamorph of this fungus. The identity of both, anamorph and teleomorph, was determined by morphological and molecular taxonomic studies, which challenges the recent new combination into Beauveria. Key words: entomogenous fungi, insect pathogens, tropical biodiversity. Introduction Fungi with cordyceps-like teleomorph are most diverse in the family Cordycipitaceae in terms of both number of known species and host range (Kobayasi 1941, Sung et al. -

A Plant Hunter's Paradise Angel Falls and Auyántepui

A Plant Hunter’s Paradise Angel Falls and Auyántepui Angel Falls ● Churún Vena ● Salto Angel Karen Angel, Editor Jimmie Angel Historical Project First Edition Copyright © 2012 Karen Angel. See page 55 for permission to use. All photographs are the property of the person or persons credited. INTRODUCTION A Plant Hunter’s Paradise - Angel Falls and Auyántepui focuses on the botanical aspects of the 28 June to 6 July 2012 “Tribute to Jimmie Angel Expedition” to Auyántepui and Angel Falls/Churún Vena/Salto Angel in Canaima National Park, State of Bolívar, Venezuela. The expedition was organized by Paul Graham Stanley of Angel-Eco Tours, Caracas, Venezuela and Karen Angel of the Jimmie Angel Historical Project, Eureka, California, U.S.A. This photo essay is a brief survey of the plants seen in Canaima National Park, Caracas and Ciudad Bolívar and is not intended to be inclusive. The sections titled Native Venezuela Botanicals (pages 13-21) and Botanicals Consumed and a few Zoological Specimens (pages 22-33) were identified by Venezuelans Jorge M. Gonzalez, an entomologist, in consultation with his botanist colleagues Balentina Milano, Angel Fernandez and Francisco Delascio. In a few cases, the photographs provided to the scientists were insufficient for a definitive identification; in these cases the identifications are “informed” based on insufficient information. Editor Karen Angel, who lives in Humboldt County, coastal northern California, uses her home region as a standard for comparison for the adaptability of the plants presented to other climate zones. Humboldt County is in USDA Hardiness Zone 9b: 25° F (-3.9°C) to 30° F (-1.1°C). -

Essía De Paula Romão Distribuição Geográfica E Potencial Das Espécies Do Gênero Tropidacris Scudder, 1869

Universidade do Estado do Pará Pró-Reitoria de Pesquisa e Pós-Graduação Centro de Ciências Naturais e Tecnologia Pós-Graduação em Ciências Ambientais – Mestrado Essía de Paula Romão Distribuição geográfica e potencial das espécies do gênero Tropidacris Scudder, 1869 (Orthoptera: Romaleidae) Belém, Pará 2017 Essía de Paula Romão Distribuição geográfica e potencial das espécies do gênero Tropidacris Scudder, 1869 (Orthoptera: Romaleidae) Dissertação apresentada como requisito parcial para obtenção do título de mestre em Ciências Ambientais no Programa de Pós-Graduação em Ciências Ambientais da Universidade do Estado do Pará. Orientadora: Dra. Ana Lúcia Nunes Gutjahr. Coorientador: Dr. Carlos Elias de Souza Braga. Belém, Pará 2017 Essía de Paula Romão Distribuição geográfica e potencial das espécies do gênero Tropidacris Scudder, 1869 (Orthoptera: Romaleidae) Dissertação apresentada como requisito parcial para obtenção do título de mestre em Ciências Ambientais no Programa de Pós-Graduação em Ciências Ambientais. Universidade do Estado do Pará. Data da defesa: 17/02/2017 Banca Examinadora _____________________________________ – Orientador(a) Profa. Dra. Ana Lúcia Nunes Gutjahr Universidade do Estado do Pará _____________________________________ – 1º Examinador(a) Profa. Dra. Cristina do Socorro Fernandes de Senna Museu Paraense Emílio Goeldi _____________________________________ – 2º Examinador(a) Prof. Dr. Antonio Sérgio Silva de Carvalho Universidade do Estado do Pará _____________________________________ – 3º Examinador(a) Profa. Dra. Veracilda Ribeiro Alves Universidade do Estado do Pará _____________________________________ – Suplente Prof. Dr. Altem Nascimento Pontes Universidade do Estado do Pará iii À toda minha família, pelo apoio na concretização deste sonho, paciência em minha ausência e, principalmente, pelo amor que nos une e fortalece mesmo com a distância. À minha vó materna Maria Regina (in memoriam), que partiu deixando muita saudade. -

Descrição Morfológica Dos Hemócitos Do Gafanhoto Tropidacris Collaris (Stoll, 1913) (Orthoptera: Romaleidae)

Descrição morfológica dos hemócitos do gafanhoto Tropidacris collaris (Stoll, 1913) (Orthoptera: Romaleidae). 57 DESCRIÇÃO MORFOLÓGICA DOS HEMÓCITOS DO GAFANHOTO TROPIDACRIS COLLARIS (STOLL, 1813) (ORTHOPTERA: ROMALEIDAE) A.A. Correia, A.V.S. Ferreira, V. Wanderley-Teixeira, A.A.C. Teixeira Universidade Federal Rural de Pernambuco, Departamento de Morfologia e Fisiologia Animal, Laboratório de Histologia, Rua Dom Manoel de Medeiros s/no, CEP 52171-900, Recife, PE, Brasil. E-mail: [email protected] RESUMO Em virtude da grande variedade na forma, função e número de hemócitos entre as diferentes espécies de insetos, a presente pesquisa teve o objetivo de descrever morfologicamente essas células presentes na hemolinfa do gafanhoto Tropidacris collaris (Stoll, 1813), por meio da microscopia de luz, utilizando-se técnica de coloração pelo Giemsa. A descrição morfológica foi realizada no Laboratório de Histologia do Departamento de Morfologia e Fisiologia Animal da Universidade Federal Rural de Pernambuco (UFRPE). Os insetos foram obtidos da criação existente no Labora- tório de Entomologia do Departamento de Biologia da UFRPE. Os resultados revelaram que a hemolinfa de T. collaris é constituída pelos seguintes hemócitos: prohemócitos, plasmócitos, coagulócitos e granulócitos. PALAVRAS-CHAVE: Hemolinfa, hemócitos, gafanhoto, Tropidacris collaris. ABSTRACT MORPHOLOGIC DESCRIPTION OF THE HEMOCYTES OF THE TROPIDACRIS COLLARIS GRASSHOPPER (STOLL, 1813) (ORTHOPTERA: ROMALEIDAE). Due to the great variety in the form, function and hemocytes number among the different species of insects, the present research had was aimed at describing the morphology of these present in the hemolymph of the Tropidacris collaris grasshopper (Stoll, 1813), by means of light microscopy, with staining by Giemsa. The morphologic description was carried out in the Laboratory of Histology of the Department of Morphology and Animal Physiology of the Rural Federal University of Pernambuco (UFRPE). -

Infecting the Grasshopper Pest Tropidacris Collaris (Orthoptera: Acridoidea: Romaleidae)

Nova Hedwigia Vol. xxx (201x) Issue x–x, xxx–xxx Article Cpublished online xxxxx xx, 2017; published in print xxxxx 201x Cordyceps locustiphila (Hypocreales: Cordycipitaceae) infecting the grasshopper pest Tropidacris collaris (Orthoptera: Acridoidea: Romaleidae) Sebastian A. Pelizza1,2*, María C.Scattolini1, Cristian Bardi1, Carlos E. Lange1,4, Sebastian A. Stenglein3 and Marta N. Cabello2,4 1 Centro de Estudios Parasitológicos y de Vectores (CEPAVE), CCT La Plata-CONICET- UNLP, Boulevard 120 s/n entre Av. 60 y Calle 64, La Plata (1900), Argentina 2 Instituto de Botánica Carlos Spegazzini (FCNyM-UNLP), Calle 53 # 477, La Plata (1900), Argentina 3 Laboratorio de Biología Funcional y Biotecnología (BIOLAB)-CICBA-INBIOTEC, Facultad de Agronomía de Azul, UNCPBA, Republica de Italia # 780, Azul (7300), Argentina 4 Comisión de Investigaciones Científicas de la Provincia de BuenosAires (CICPBA) With 3 figures Abstract: Cordyceps locustiphila is described, illustrated, and compared with a previous finding. This species was collected infecting Tropidacris collaris in the Yabotí biosphere reserve, Misiones province, Argentina. Until now, this entomopathogenic fungus has not been reported affecting T. collaris, and it is the first report for Argentina. From the cordyceps-like stromata of C. locustiphila it was possible to isolate for the first time the acremonium-like anamorph of this fungus. The identity of both, anamorph and teleomorph, was determined by morphological and molecular taxonomic studies, which challenges the recent Proofsnew combination into Beauveria. Key words: entomogenous fungi, insect pathogens, tropical biodiversity. Introduction Fungi with cordyceps-like teleomorph are most diverse in the family Cordycipitaceae in terms of both number of known species and host range (Kobayasi 1941, Sung et al. -

Tropidacris Cristata (Giant Grasshopper) Order: Orthoptera (Grasshoppers and Crickets) Class: Insecta (Insects) Phylum: Arthropoda (Arthropods)

UWI The Online Guide to the Animals of Trinidad and Tobago Ecology Tropidacris cristata (Giant Grasshopper) Order: Orthoptera (Grasshoppers and Crickets) Class: Insecta (Insects) Phylum: Arthropoda (Arthropods) Fig. 1. Giant grasshopper, Tropidacris cristata. [http://www.backyardnature.net/yucatan/biggrass.htm, downloaded 29 March 2015] TRAITS. The giant grasshoppers (genus Tropidacris) of South and Central America have a body length of about 10cm and a wingspan of about 18cm and are some of the largest insects in the world (Carbonell, 1986). Two species, Tropidacris cristata and the similar Tropidacris collaris, range within South America north of the southern cone. The name Tropidacris dux is also sometimes used, but this now refers to a subspecies of T. cristata. Only T. cristata is found in Trinidad, this species has mainly orange hindwings (Carbonell, 1984) (Fig. 2). T. collaris has yellow antennae and green to blue hindwings. The nymphs (immature stages) show warning coloration of black and yellow (Fig. 3) and are often found in groups, while the adults are well camouflaged in vegetation. The forewings resemble leaves while the hindwings possess a striking coloration (Rowell, 1983). UWI The Online Guide to the Animals of Trinidad and Tobago Ecology DISTRIBUTION. Adult Tropidacris ranges around South America, north of the southern cone and are often encountered along areas of the Caribbean coast and the llanos region of Venezuela (Starr, 1998). The habitat range for T. collaris shows a wide range from humid forest to more open, drier formations and T. cristata is largely lacking from open, dry formations (Carbonell, 1986). HABITAT AND ACTIVITY. The giant grasshopper is not often encountered in large numbers but can be found in more open drier formations in a humid forest. -

Banana Weevil Borer (Cosmopolites Sordidus): Plant Defense Responses

FACULTY OF AGRICULTURAL SCIENCES INSTITUTE OF CROP SCIENCE SECTION of CROP PHYSIOLOGY OF SPECIALTY CROPS (340F) UNIVERSITY OF HOHENHEIM SUPERVISOR: PROF. DR. JENS NORBERT WÜNSCHE (RIP)/ PROF. DR. CHRISTIAN ZÖRB Banana weevil borer (Cosmopolites sordidus): Plant defense responses and Control options Dissertation Submitted in fulfillment of the regulation to acquire the degree “Doktor der Agrarwissenschaften” (Dr.Sc.agr.in Agricultural Sciences) to the Faculty of Agricultural Sciences Presented by Elyeza Bakaze Born in Luwero, Uganda -2021- i This thesis was accepted as a doctoral dissertation in fulfilment of the requirement for the degree ‘Doktor der Agrarwissenschaften’ by the Faculty of Agricultural Sciences at University of Hohenheim on 14h October 2020. Date of Oral examination: 15th March 2021 Examination Committee Supervisor and Reviewer: Prof. Dr. Jens Wünsche (RIP)/ Prof. Dr. Christian Zörb Co-Reviewer: Prof. Dr. Jens Poetsch Additional examiner: Prof. Dr. Claus P.W. Zebitz Dean and Head of the committee: Prof. Dr. Martin Hasselmann ii ACKNOWLEDGMENT I extend my sincere gratitude to Prof. Dr. Jens Wünsche (RIP) for his relentless kindness and moral support, encouragement, and guidance that made this research possible. Also, I thank Prof. Dr. Christian Zörb, who accepted to take up the supervisory role of Prof. Dr. Jens Wünsche when his creator called him, thank you sir. I would like to thank Prof. Dr. Dr. C.P.W Zebitz for being my second supervisor and his knowledge about entomopathogenic fungi that greatly complimented my work substantially. And Prof. Dr. Jens Poetsch thank you for reviewing this thesis. This research would not have been possible without the help of Beloved Dzomeku and his team at CSIR-Crops Research Institute Kumasi. -

Animals in the Nambiquara Diet: Methods of Collection and Processing

/. Ethnobiol. 11(1):1-22 Summer 1991 ANIMALS IN THE NAMBIQUARA DIET: METHODS OF COLLECTION AND PROCESSING ELEONORE ZULNARA FREIRE SETZ Departmento de Zoologia - IB Universidade Estadual de Campinas - CP 6109 13081 Ca1npinas, Sao Paulo, Brazil ABSTRACT.-This study reports items of animal origin observed to be consumed in two Nambiquara Indian villages and describes how these foods were obtained and processed. The Alantesu village (A) is located in the forest of the Guapore Valley and Juina (J), in the cerrado (savanna) of the Chapada dos Parecis, both in the state of Mato Grosso, western Brazil. Although similar methods were used to obtain and process animal items, the two villages presented clear dif ferences in the taxonomic composition of these items (A, more fishes; J, more insects and birds, for example) and the total number of species (A: 69 spp. vs. J: 90 spp.) observed in the diet. Qualitative and quantitative differences in the fauna in the neighborhood of each village largely explain the dietary differences. The methods by which items were obtained and processed by the two popula tions did not differ much, not only because they shared the basic southern Nambiquara culture, but also because the behaviors of the major food species are similar. The cerrado group possessed special techniques for gathering grass hopper nymphs and winged termites whereas the forest group used a wider variety of fishing techniques; each technology is associated with the greater availability of the animals being targeted. RESUMO.-Este estudo relata os itens de origem animal cujo consumo foi obser vado em"duas aldeias indlgenas Nambiquara durante perlodos padronizados de observasao e descreve como estes alimentos foram obtidos e processados." A aldeia Alantesu (A) localiza-se na floresta do Vale do Guapore e a Juina (J), no cerrado da Chapada dos Parecis, ambas no estado do Mato Grosso, Brasil. -

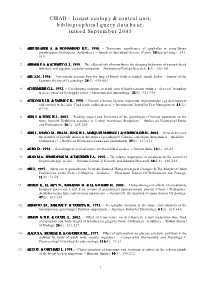

CIRAD - Locust Ecology & Control Unit, Bibliographical Query Database, Issued September 2005

CIRAD - Locust ecology & control unit, bibliographical query database, issued September 2005 1. ABDULGADER A. & MOHAMMAD K.U., 1990. – Taxonomic significance of epiphallus in some Libyan grasshoppers (Orthoptera: Acridoidea ). – Annals of Agricultural Science (Cairo), 3535(special issue) : 511- 519. 2. ABRAMS P.A. & SCHMITZ O.J., 1999. – The effect of risk of mortality on the foraging behaviour of animals faced with time and digestive capacity constraints. – Evolutionary Ecology Research, 11(3) : 285-301. 3. ABU Z.N., 1998. – A nematode parasite from the lung of Mynah birds at Jeddah, Saudi Arabia. – Journal of the Egyptian Society of Parasitology, 2828(3) : 659-663. 4. ACHTEMEIER G.L., 1992. – Grasshopper response to rapid vertical displacements within a “clear air” boundary layer as observed by doppler radar. – Environmental Entomology, 2121(5) : 921-938. 5. ACKONOR J.B. & VAJIME C.K., 1995. – Factors affecting Locusta migratoria migratorioides egg development and survival in the Lake Chad basin outbreak area. – International Journal of Pest Management, 44111(2) : 87-96. 6. ADIS J. & JUNK W.J., 2003. – Feeding impact and bionomics of the grasshopper Cornops aquaticum on the water hyacinth Eichhornia crassipes in Central Amazonian floodplains. – Studies on Neotropical Fauna and Environment, 3838(3) : 245-249. 7. ADIS J., LHANO M., HILL M., JUNK W.J., MARQUES MARINEZ I. & OBEOBERHOLZERRHOLZER H., 2004. – What determines the number of juvenile instars in the tropical grasshopper Cornops aquaticum (Leptysminae : Acrididae : Orthoptera) ? – Studies on Neotropical Fauna and Environment, 3939(2) : 127-132. 8. AGRO D., 1994. – Grasshoppers as food source for black-billed cuckoo. – Ontario Birds, 1212(1) : 28-29. 9. AHAD M.A., SHAHJAHAN M.