Misunderstanding + Misinformation = Mistrust

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Identity Crisis: Ethnicity and Conflict in Myanmar

Identity Crisis: Ethnicity and Conflict in Myanmar Asia Report N°312 | 28 August 2020 Headquarters International Crisis Group Avenue Louise 235 • 1050 Brussels, Belgium Tel: +32 2 502 90 38 • Fax: +32 2 502 50 38 [email protected] Preventing War. Shaping Peace. Table of Contents Executive Summary ................................................................................................................... i I. Introduction ..................................................................................................................... 1 II. A Legacy of Division ......................................................................................................... 4 A. Who Lives in Myanmar? ............................................................................................ 4 B. Those Who Belong and Those Who Don’t ................................................................. 5 C. Contemporary Ramifications..................................................................................... 7 III. Liberalisation and Ethno-nationalism ............................................................................. 9 IV. The Militarisation of Ethnicity ......................................................................................... 13 A. The Rise and Fall of the Kaungkha Militia ................................................................ 14 B. The Shanni: A New Ethnic Armed Group ................................................................. 18 C. An Uncertain Fate for Upland People in Rakhine -

Vidya Tama Saputra.Pdf

DigitalDigital RepositoryRepository UniversitasUniversitas JemberJember DISKRIMINASI ETNIS ROHINGYA OLEH PEMERINTAH MYANMAR DISCRIMINATION AGAINST ETHNIC ROHINGYA BY GOVERNMENT OF MYANMAR SKRIPSI diajukan guna melengkapi tugas akhir dan memenuhi syarat-syarat untuk menyelesaikan Program Studi Ilmu Hubungan Internasional (S1) dan mencapai gelar Sarjana Sosial Oleh: VIDYA TAMA SAPUTRA NIM 050910101033 JURUSAN ILMU HUBUNGAN INTERNASIONAL FAKULTAS ILMU SOSIAL DAN ILMU POLITIK UNIVERSITAS JEMBER 2010 DigitalDigital RepositoryRepository UniversitasUniversitas JemberJember HALAMAN PERSEMBAHAN Skripsi ini penulis persembahkan untuk: 1.) Almamater Fakultas Ilmu Sosial dan Ilmu Politik Universitas Jember; 2.) Keluarga dan teman-teman yang telah memberikan dukungan untuk penyelesaian skripsi ini; 3.) Pihak-pihak lainnya yang tidak mungkin disebutkan secara keseluruhan, penulis sampaikan terima kasih atas dukungannya. ii DigitalDigital RepositoryRepository UniversitasUniversitas JemberJember MOTTO “Jadilah Orang Baik” iii DigitalDigital RepositoryRepository UniversitasUniversitas JemberJember HALAMAN PERNYATAAN Saya yang bertanda tangan di bawah ini. Nama : Vidya Tama Saputra NIM : 050910101033 Menyatakan dengan sesungguhnya bahwa karya tulis ilmiah yang berjudul: ” Diskriminasi Etnis Rohingya Oleh Pemerintah Myanmar” adalah benar-benar hasil karya sendiri, kecuali jika disebutkan sumbernya dan belum pernah diajukan pada institusi manapun, serta bukan karya jiplakan. Saya bertanggung jawab atas keabsahan kebenaran isinya sesuai dengan sikap ilmiah -

MYANMAR Buthidaung, Maungdaw, and Rathedaung Townships / Rakhine State

I Complex MYANMAR Æ Emergency Buthidaung, Maungdaw, and Rathedaung Townships / Rakhine State Imagery analysis: 31 August - 11 October 2017 | Published 17 November 2017 | Version 1.1 CE20130326MMR N 92°11'0"E 92°18'0"E 92°25'0"E 92°32'0"E 92°39'0"E 92°46'0"E 92°53'0"E N " " 0 ' 0 ' 5 5 Thimphu 2 2 ° ° 1 1 ¥¦¬ 2 Number of affected 2 C H I N A Township I N D I A settlements ¥¦¬Dhaka Buthidaung 34 Hano¥¦¬i Kyaung Toe Maungdaw 225 N Gu Mi Yar N " M YA N M A R " 0 ' 0 ' Naypyidaw 8 8 ¥¦¬ 1 Rathedaung 16 1 ° ° 1 Vientiane 1 2 Map location 2 ¥¦¬ Taing Bin Gar T H A I L A N D Baw Taw Lar Mi Kyaung Chaung Thit Tone Nar Gwa Son Bangkok ¥¦¬ Ta Man Thar Ah Nauk Rakhine Phnom Penh Ta Man Thar Thea Kone Tan Yae Nauk Ngar Thar N N " ¥¦¬ " 0 ' 0 Tat Chaung ' 1 Ye Aung Chaung 1 1 1 ° ° 1 Than Hpa Yar 1 2 Pa Da Kar Taung Mu Hti 2 Kyaw U Let Hpweit Kya Done Ku Lar Kyun Taung Destroyed areas in Buthidaung, Kyet Kyein See inset for close-up view of Maungdaw, and Rathedaung Kyun Pauk Sin Oe San Kar Pin Yin destroyed structures Kyun Pauk Pyu Su Goke Pi Townships of Rakhine State in Hpaw Ti Kaung N Thaung Khu Lar N " " 0 ' 0 ' 4 Gyit Chaung 4 Myanmar ° Sa Bai Kone ° 1 1 2 Lin Bar Gone Nar 2 This map illustrates areas of satellite- Pyaung Pyit detected destroyed or otherwise damaged Yin Ma Kyaung Taung Tha Dut Taung settlements in Buthidaung, Maungdaw, and Yin Ma Zay Kone Taung Rathedaung Townships in the Maungdaw and Sittwe Districts of Rakhine State in Myanmar. -

Statelessness in Myanmar

Statelessness in Myanmar Country Position Paper May 2019 Country Position Paper: Statelessness in Myanmar CONTENTS Summary of main issues ..................................................................................................................... 3 Relevant population data ................................................................................................................... 4 Rohingya population data .................................................................................................................. 4 Myanmar’s Citizenship law ................................................................................................................. 5 Racial Discrimination ............................................................................................................................... 6 Arbitrary deprivation of nationality ....................................................................................................... 7 The revocation of citizenship.................................................................................................................. 7 Failure to prevent childhood statelessness.......................................................................................... 7 Lack of naturalisation provisions ........................................................................................................... 8 Civil registration and documentation practices .............................................................................. 8 Lack of Access and Barriers -

Print This Article

Volume 22, Number 1, 2015 ﺍﻟﺴﻨﺔ ﺍﻟﺜﺎﻧﻴﺔ ﻭﺍﻟﻌﺸﺮﻭﻥ، ﺍﻟﻌﺪﺩ ١، ٢٠١٥ : W C I I - C C M. A. Kevin Brice ﺍﻟﺸﻮﻛﺔ ﺍﻟﺴﻴﺎﺳﻴﺔ ﻟﻸﻓﻜﺎﺭ ﺍﻟﺪﻳﻨﻴﺔ: C C M’ ﺍﻟﺤﺮﻛﺔ ﺍﻟﺘﺠﺪﻳﺪﻳﺔ ﺍﻻﺳﻼﻣﻴﺔ D T: C S R ﻭﺍﻟﻄﺮﻳﻖ ﺇﻟﻰ ﻧﻘﻄﺔ ﺍﻟﺘﻘﺎﺀ ﺍﻻﺳﻼﻡ ﻭﺍﻟﺪﻭﻟﺔ Ahmad Suaedy & Muhammad Haz ﻋﻠﻲ ﻣﻨﺤﻨﻒ S M C I B: T ﺍﻻﺳﻼﻡ ﻭﺍﻟﻤﻼﻳﻮ ﻭﺍﻟﺴﻴﺎﺩﺓ ﻓﻲ ﺍﻟﻤﺤﻴﻂ: I S G P ﺳﻠﻄﻨﺔ ﺑﺮﻭﻧﺎﻱ ﻭﺍﻻﺳﺘﻌﻤﺎﺭ ﺍﻻﻭﺭﺑﻲ ﻓﻲ ﺑﻮﺭﻧﻴﻮ Friederike Trotier ﺩﺍﺩﻱ ﺩﺍﺭﻣﺎﺩﻱ E-ISSN: 2355-6145 STUDIA ISLAMIKA STUDIA ISLAMIKA Indonesian Journal for Islamic Studies Vol. 22, no. 1, 2015 EDITOR-IN-CHIEF Azyumardi Azra MANAGING EDITOR Ayang Utriza Yakin EDITORS Saiful Mujani Jamhari Jajat Burhanudin Oman Fathurahman Fuad Jabali Ali Munhanif Saiful Umam Ismatu Ropi Dadi Darmadi INTERNATIONAL EDITORIAL BOARD M. Quraish Shihab (Syarif Hidayatullah State Islamic University of Jakarta, INDONESIA) Tauk Abdullah (Indonesian Institute of Sciences (LIPI), INDONESIA) Nur A. Fadhil Lubis (State Islamic University of Sumatera Utara, INDONESIA) M.C. Ricklefs (Australian National University, AUSTRALIA) Martin van Bruinessen (Utrecht University, NETHERLANDS) John R. Bowen (Washington University, USA) M. Kamal Hasan (International Islamic University, MALAYSIA) Virginia M. Hooker (Australian National University, AUSTRALIA) Edwin P. Wieringa (Universität zu Köln, GERMANY) Robert W. Hefner (Boston University, USA) Rémy Madinier (Centre national de la recherche scientique (CNRS), FRANCE) R. Michael Feener (National University of Singapore, SINGAPORE) Michael F. Laffan (Princeton University, USA) ASSISTANT TO THE EDITORS Testriono Muhammad Nida' Fadlan ENGLISH LANGUAGE ADVISOR Shirley Baker ARABIC LANGUAGE ADVISOR Nursamad Tb. Ade Asnawi COVER DESIGNER S. Prinka STUDIA ISLAMIKA (ISSN 0215-0492; E-ISSN: 2355-6145) is an international journal published by the Center for the Study of Islam and Society (PPIM) Syarif Hidayatullah State Islamic University of Jakarta, INDONESIA. -

Languages in the Rohingya Response

Languages in the Rohingya response This overview relates to a Translators without Borders (TWB) study of the role of language in humanitarian service access and community relations in Cox’s Bazar, Bangladesh and Sittwe, Myanmar. Language use and word choice has implications for culture, identity and politics in the Myanmar context. Six languages play a role in the Rohingya response in Myanmar and Bangladesh. Each brings its own challenges for translation, interpretation, and general communication. These languages are Bangla, Chittagonian, Myanmar, Rakhine, Rohingya, and English. Bangla Bangla’s near-sacred status in Bangladeshi society derives from the language’s tie to the birth of the nation. Bangladesh is perhaps the only country in the world which was founded on the back of a language movement. Bangladeshi gained independence from Pakistan in 1971, among other things claiming their right to use Bangla and not Urdu. Bangladeshis gave their lives for the cause of preserving their linguistic heritage and the people retain a patriotic attachment to the language. The trauma of the Liberation War is still fresh in the collective memory. Pride in Bangla as the language of national unity is unique in South Asia - a region known for its cultural, religious, and linguistic diversity. Despite the elevated status of Bangla, the country is home to over 40 languages and dialects. This diversity is not obvious because Bangladeshis themselves do not see it as particularly important. People across the country have a local language or dialect apart from Bangla that is spoken at home and with neighbors and friends. But Bangla is the language of collective, national identity - it is the language of government, commerce, literature, music and film. -

Crimes Against Humanity the Case of the Rohingya People in Burma

Crimes Against Humanity The Case of the Rohingya People in Burma Prepared By: Aydin Habibollahi Hollie McLean Yalcin Diker INAF – 5439 Report Presentation Ethnic Distribution Burmese 68% Shan 9% Karen 7% Rakhine 4% Chinese 3% IdiIndian 2% Mon 2% Other 5% Relig ious Dis tr ibu tion Buddhism 89% Islam & Christianity Demography Burmese government has increased the prominence of the Bu ddhis t relig ion to the de tr imen t of other religions. Rohingya Organization • ~1% of national population • ~4% of Arakan population • ~45% of Muslim population Rohingya Organization • AkArakan RRhiohingya NNiational Organi zati on (ARNO) • Domestically not represented Cause of the Conflict • Persecution and the deliberate targggeting of the Rohdhl18hingya started in the late 18th century whhhen the Burmese occupation forced large populations of both the Rohingya Muslims and the Arakanese Buddhists to flee the Ara kan stttate. • The Takhine Party, a predominant anti-colonial faction, began to provoke the Arakanese Buddhists agains t the Ro hingya Mus lims convinc ing the Buddhists that the Islamic culture was an existential threat to their people. • The seed of ha tre d be tween the two sides was plan te d by the Takhine Party and the repression began immediately in 1938 when the Takhine Party took control of the newly independent state. Current Status • JJ,une and October 2012, sectarian violence between the Rohingya Muslims and the Arakanese Buddhist killed almost 200 people, destroyed close to 10,000 homes and displaced 127, 000. A further 25, 000 Rohingya fled to Bangladesh, India, Malaysia, Sir Lanka, and Thailand. • Tensions are still high between Rohingya Muslims and Arakanese Buddhists and human rights violations persitist. -

(SEPT. 2020) Mercy Corps - Market Analysis Unit October 29Th, 2020

MARKET PRICE REPORT – RAKHINE STATE (SEPT. 2020) Mercy Corps - Market Analysis Unit October 29th, 2020 As part of its cash and voucher assistance programs in Rakhine State, Mercy Corps gathers market prices at town markets in Central and Northern Rakhine State. This monthly market price report summarizes median product prices, based on data from three vendors per product per market. Data were gathered September 21-29 in Ponnagyun, Maungdaw, Sittwe, Mrauk U, and Minbya Townships. Data for May and July 2020 are also provided for comparison in section two.1 Highlights: September 2020 September food prices were generally higher in Maungdaw than other townships, while food prices were lower in Ponnagyun. Among essential food items, pulse prices were most consistent across townships. Vegetables prices varied by township, particularly for green chili and bamboo shoots. Vegetable prices in Minbya were slightly lower than elsewhere in September. Prices for kitchen goods were slightly higher in Maungdaw and lower in Sittwe. Prices in Maungdaw tracked closest to other townships for shelter goods. From May to September, Maungdaw prices were often higher than elsewhere for essential food items, while Ponnagyun prices were more often lower. Table 1. Market Prices in this Report (by Category) Essential food items High-quality (better) rice, low-quality (cheaper) rice, palm oil, salt, and pulses. Vegetables Green chili, long bean, potato, onion, bamboo shoot, etc. Shelter goods Blankets, mosquito nets, plastic mats, plastic tarps, towels, etc. Kitchen goods Plates, cooking spoons, kitchen knives, cooking pots, cups, etc. Other goods Hygiene products, fish/shrimp, various household products, etc. I. Market Prices: September 2020 (by Category) Essential Food Items – Essential food prices exhibited some variation across townships in September, with the exception of pulses. -

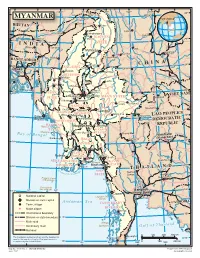

Map of Myanmar

94 96 98 J 100 102 ° ° Indian ° i ° ° 28 n ° Line s Xichang Chinese h a MYANMAR Line J MYANMAR i a n Tinsukia g BHUTAN Putao Lijiang aputra Jorhat Shingbwiyang M hm e ra k Dukou B KACHIN o Guwahati Makaw n 26 26 g ° ° INDIA STATE n Shillong Lumding i w d Dali in Myitkyina h Kunming C Baoshan BANGLADE Imphal Hopin Tengchong SH INA Bhamo C H 24° 24° SAGAING Dhaka Katha Lincang Mawlaik L Namhkam a n DIVISION c Y a uan Gejiu Kalemya n (R Falam g ed I ) Barisal r ( r Lashio M a S e w k a o a Hakha l n Shwebo w d g d e ) Chittagong y e n 22° 22° CHIN Monywa Maymyo Jinghong Sagaing Mandalay VIET NAM STATE SHAN STATE Pongsali Pakokku Myingyan Ta-kaw- Kengtung MANDALAY Muang Xai Chauk Meiktila MAGWAY Taunggyi DIVISION Möng-Pan PEOPLE'S Minbu Magway Houayxay LAO 20° 20° Sittwe (Akyab) Taungdwingyi DEMOCRATIC DIVISION y d EPUBLIC RAKHINE d R Ramree I. a Naypyitaw Loikaw w a KAYAH STATE r r Cheduba I. I Prome (Pye) STATE e Bay Chiang Mai M kong of Bengal Vientiane Sandoway (Viangchan) BAGO Lampang 18 18° ° DIVISION M a e Henzada N Bago a m YANGON P i f n n o aThaton Pathein g DIVISION f b l a u t Pa-an r G a A M Khon Kaen YEYARWARDY YangonBilugyin I. KAYIN ATE 16 16 DIVISION Mawlamyine ST ° ° Pyapon Amherst AND M THAIL o ut dy MON hs o wad Nakhon f the Irra STATE Sawan Nakhon Preparis Island Ratchasima (MYANMAR) Ye Coco Islands 92 (MYANMAR) 94 Bangkok 14° 14° ° ° Dawei (Krung Thep) National capital Launglon Bok Islands Division or state capital Andaman Sea CAMBODIA Town, village TANINTHARYI Major airport DIVISION Mergui International boundary 12° Division or state boundary 12° Main road Mergui n d Secondary road Archipelago G u l f o f T h a i l a Railroad 0 100 200 300 km Chumphon The boundaries and names shown and the designations Kawthuang 10 used on this map do not imply official endorsement or ° acceptance by the United Nations. -

Burma (Myanmar) Rohingya Refugee Wellness Country Guide

Overview and Context e a d The history of the Rohingya people in Burma (Myanmar) dates i y back to the 15th century. Despite this history in Burma, the u g Rohingya are not viewed as legal citizens or recognized as one of G the 135 official ethnic groups within Burma. The Rohingya primarily n live in the Rakhine (Arakan) state, the poorest state in Burma. In y r i 1982, the Burmese government rescinded the Rohingya’s t citizenship status, severely limiting their ability to vote, travel, or own h n property. Although democratic elections were held in 2012, u Rohingya have faced increased violence perpetrated by the o o government since 2012, including mass rape, torture, and killings. C R Rohingya identity cards were canceled in 2015, further limiting movement, and rendering the Rohingya essentially stateless. s ) s r As a result of this ongoing discrimination, approximately 120,000 Rohingya have been internally displaced, e n 1,000,000 Rohingya have fled to Bangladesh, and 150,000 have fled to Malaysia. The Rohingya are referred to a l by some as the “most persecuted group in the world.” Many believe the atrocities committed against this group l are tantamount to genocide. e m W n Country Info Mental Health Profile e a Population e Research suggests Rohingyan refugees who have g y fled to refugee camps experience high levels of Approximately 1 million live u stress associated with the restrictions of camp life, f in Burma (Myanmar) M such as lack of freedom of movement, safety e concerns, and food scarcity. -

The Rohingya Origin Story: Two Narratives, One Conflict

Combating Extremism SHAREDFACT SHEET VISIONS The Rohingya Origin Story: Two Narratives, One Conflict At the center of the Rohingya Crisis is a question about the group’s origin. It is in this identity, and the contrasting histories that the two sides claim (i.e., the Rohingya minority and the Buddhist government/some civilians), where religion and politics collide. Although often cast as a religious war, the contemporary conflict didn’t exist until World War II, when the minority Muslim Rohingya sided with British colonial rulers, while the Buddhist majority allied with the invading Japanese. However, it took years for the identity politics to fully take root. It was 1982, when the Rohingya were stripped of their citizenship by law (For more on this, see “Q&A on the Rohingya Crisis & Buddhist Extremism in Myanmar”). Myanmarese army commander Senior General Min Aung Hlaing made it clear that Rohingya origin lay at the heart of the matter when, on September 16, 2017, he posted to Facebook a statement saying that the current military action against the Rohingya is “unfinished business” stemming back to the Second World War. He also stated, “They have demanded recognition as Rohingya, which has never been an ethnic group in Myanmar. [The] Bengali issue is a national cause and we need to be united in establishing the truth.”i This begs the question, what is the truth? There is no simple answer to this question. At the present time, there are two dominant, opposing narratives regarding the Rohingya ethnic group’s history: one from the Rohingya perspective, and the other from the neighboring Rakhine and Bamar peoples. -

CENTRALIZED NATIONAL RISK ASSESSMENT for MYANMAR 2018 – 1 of 178 –

Centralized National Risk Assessment for Myanmar FSC-CNRA-MM V1-0 EN FSC-CNRA-MM V1-0 CENTRALIZED NATIONAL RISK ASSESSMENT FOR MYANMAR 2018 – 1 of 178 – Title: Centralized National Risk Assessment for Myanmar Document reference FSC-CNRA-MM V1-0 EN code: Approval body: FSC International Center: Performance and Standards Unit Date of approval: 27 August 2018 Contact for comments: FSC International Center - Performance and Standards Unit - Adenauerallee 134 53113 Bonn, Germany +49-(0)228-36766-0 +49-(0)228-36766-30 [email protected] © 2018 Forest Stewardship Council, A.C. All rights reserved. No part of this work covered by the publisher’s copyright may be reproduced or copied in any form or by any means (graphic, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, recording taping, or information retrieval systems) without the written permission of the publisher. Printed copies of this document are for reference only. Please refer to the electronic copy on the FSC website (ic.fsc.org) to ensure you are referring to the latest version. The Forest Stewardship Council® (FSC) is an independent, not for profit, non- government organization established to support environmentally appropriate, socially beneficial, and economically viable management of the world’s forests. FSC’s vision is that the world’s forests meet the social, ecological, and economic rights and needs of the present generation without compromising those of future generations. FSC-CNRA-MM V1-0 CENTRALIZED NATIONAL RISK ASSESSMENT FOR MYANMAR 2018 – 2 of 178 – Contents Risk assessments that have been finalized for Myanmar .......................................... 4 Risk designations in finalized risk assessments for Myanmar ...................................