Empire of Prisons: Reading Roland Barthes and Hijikata Tatsumi in the Animus of Laughter

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Vibrations of Emptiness ❙

from Croatian stages: Vibrations of Emptiness ❙ A review of the performance SJENA (SHADOW) by MARIJA ©ΔEKIΔ ❙ Iva Nerina Sibila The same stream of life that runs through my veins One thing is certain, the question about the meaning and night and day runs through the world and dances approach to writing about dance comes to a complete halt in rhythmic measures. when the task at hand is writing about an exceptional per- formance. Such performances offer us numerous forays into It is the same life that shoots in joy through the dust of the world of the author, numerous interpretations and analy- the earth in numberless blades of grass and breaks into ses, as well as reasons why to write about it. I believe that tumultuous waves of leaves and flowers. Shadow, which is the impetus for this text, is one such per- formance. It is the same life that is rocked in the ocean-cradle of birth and of death, in ebb and in flow. Implosion of Opposites Travelling within the space of Shadow, we encounter a I feel my limbs are made glorious by the touch of this series of opposite notions. Art ∑ science, East ∑ West, body world of life. And my pride is from the life-throb of ages ∑ spirit, improvisation ∑ choreography, male ∑ female, young dancing in my blood this moment. ∑ old are all dualities that are continuously repeated no mat- Tagore ter which direction the analysis takes. Treated in the pre-text of Marija ©ÊekiÊ and her associ- ates these oppositions do not cancel each other out, do not I recently participated in a discussion on the various ways join together, do not enter into conflict, nor confirm each in which one can write about a dance performance. -

The Sought for Butoh Body: Tatsumi Hijikata's Cultural Rejection And

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by DSpace at Waseda University Transcommunication Vol.3-1 Spring 2016 Graduate School of International Culture and Communication Studies Article The Sought For Butoh Body: Tatsumi Hijikata’s Cultural Rejection and Creation Julie Valentine Dind Abstract This paper studies the influence of both Japanese and Western cultures on Hijikata Tatsumi’s butoh dance in order to problematize the relevance of butoh outside of the cultural context in which it originated. While it is obvious that cultural fusion has been taking place in the most recent developments of butoh dance, this paper attempts to show that the seeds of this cultural fusion were already present in the early days of Hijikata’s work, and that butoh dance embodies his ambivalence toward the West. Moreover this paper furthers the idea of a universal language of butoh true to Hijikata’s search for a body from the “world which cannot be expressed in words”1 but only danced. The research revolves around three major subjects. First, the shaping power European underground literature and German expressionist dance had on Hijikata and how these influences remained present in all his work throughout his entire career. Secondly, it analyzes the transactions around the Japanese body and Japanese identity that take place in the work of Hijikata in order to see how Western culture might have acted as much as a resistance as an inspiration in the creation of butoh. Third, it examines the unique aspects of Hijikata’s dance, in an attempt to show that he was not only a product of his time but also aware of the shaping power of history and actively fighting against it in his quest for a body standing beyond cultural fusion or history. -

Raquel Almazan

RAQUEL ALMAZAN RAQUEL.ALMAZAN@ COLUMBIA.EDU WWW.RAQUELALMAZAN.COM SUMMARY Raquel Almazan is an actor, writer, director in professional theatre / film / television productions. Her eclectic career as artist-activist spans original multi- media solo performances, playwriting, new work development and dramaturgy. She is a practitioner of Butoh Dance and creator/teacher of social justice arts programs for youth/adults, several focusing on social justice. Her work has been featured in New York City- including Off-Broadway, throughout the United States and internationally in Greece, Italy, Slovenia, Colombia, Chile, Guatemala and Sweden; including plays within her lifelong project on writing bi-lingual plays in dedication to each Latin American country (Latin is America play cycle). EDUCATION MFA Playwriting, School of the Arts Columbia University, New York City BFA Theatre Performance/Playwriting University of Florida-New World School of With honors the Arts Conservatory, Miami, Florida AA Film Directing Miami Dade College, Miami Florida PLAYWRITING – Columbia University Playwriting through aesthetics/ Playwriting Projects: Charles Mee Play structure and analysis/Playwriting Projects: Kelly Stuart Thesis and Professional Development: David Henry Hwang and Chay Yew American Spectacle: Lynn Nottage Political Theatre/Dramaturgy: Morgan Jenness Collaboration Class- Mentored by Ken Rus Schmoll Adaptation: Anthony Weigh New World SAC Master Classes Excerpt readings and feedback on Blood Bits and Junkyard Food plays: Edward Albee Writing as a career- -

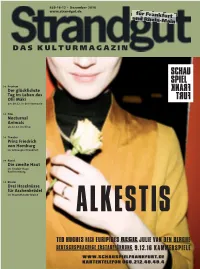

D a S K U L T U R M a G a Z

459-16-12 s Dezember 2016 www.strandgut.de für Frankfurt und Rhein-Main D A S K U L T U R M A G A Z I N >> Preview Der glücklichste Tag im Leben des Olli Mäki am 14.12. in der Harmonie >> Film Nocturnal Animals ab 22.12. im Kino >> Theater Prinz Friedrich von Homburg im Schauspiel Frankfurt >> Kunst Die zweite Haut im Sinclair-Haus Bad Homburg >> Kinder Drei Haselnüsse für Aschenbrödel im Staatstheater Mainz ALKESTIS TED HUGHES NACH EURIPIDES REGIE JULIE VAN DEN BERGHE DEUTSCHSPRACHIGE ERSTAUFFÜHRUNG 9.12.16 KAMMERSPIELE WWW.SCHAUSPIELFRANKFURT.DE KARTENTELEFON 069.212.49.49.4 INHALT Film 4 Das unbekannte Mädchen von Jean-Pierre & Luc Dardenne 6 Nocturnal Animals von Tom Ford 7 Paula von Christian Schwochow 8 abgedreht Sully © Warner Bros. 8 Frank Zappa – Eat That Question von Thorsten Schütte 9 Treppe 41 10 Filmstarts Preview Zwischen Wachen 5 Der glücklichste Tag im Leben des Olli Mäki und Träumen Frank Zappa © Frank Deimel »Nocturnal Animals« von Tom Ford Theater Schon in den ersten Bildern 17 Tanztheater 6 herrscht ein beunruhigender 18 Der Nussknacker im Staatstheater Darmstadt Widerspruch zwischen abstoßender 19 Late Night Hässlichkeit und perfektionistischer in der Schmiere Ästhetik: Zu sehen ist in Zeitlupe wa- 20 Hass berndes Fleisch von alten, grotesk auf den Landungsbrücken 20 vorgeführt fetten Frauenkörpern vor einem Das unbekannte Mädchen 21 Jesus und Novalis leuchtend roten Vorhang. Die Da- bei Willy Praml men sind Teil einer Ausstellung, die 22 Kafka/Heimkehr die Galeristin Susan Morrow (Amy in der Wartburg Wiesbaden 23 Prinz Friedrich von Homburg Adams) kuratiert hat. -

Encore Companies Inc

November 2002 BAM 20th Next Wave Festival Yoshllorno Nara, Meltln, Moon No.2, 2002 BAM 20th Next Wave Festival is sponsored by: PHILIP MORRIS ENCORE COMPANIES INC. Brooklyn Academy of Music Alan H. Fishman William I. Campbell Chairman of the Board Vice Chairman of the Board Karen Brooks Hopkins Joseph V. Melillo President Executive Producer presents Hibi ki (Resonance from Far Away) Approximate Sankai Juku running time: BAM Howard Gilman Opera House 1 hour and 30 Nov 19, 21-23, 2002 at 7:30pm minutes with no Nov 24 at 3pm intermission Directed, choreographed, and designed by Ushio Amagatsu Music by Takashi Kako & Yoichiro Yoshikawa Dancers Ushio Amagatsu, Semimaru, Toru Iwashita, Sho Takeuchi, Akihito Ichihara, Tayiyo Tochiaki Stage manager Yuji Kobayashi Set technician Kenichi Yonekura Lighting technician Genta Iwamura Sound technician Akira Aikawa Company manager Ming Y. Ng Co-commissioned and co-produced by Theatre de la Ville, Paris; Hancher Auditorium, University of Iowa; Biwako Hall, Center for the Performing Arts, Shiga North American management Extremetaste Ltd. Next Wave Dance support is provided by The Harkness Foundation for Dance. Presentation support is provided by The Bodman Foundation. Additional support is provided by Asian Cultural Council. BAM 20th Next Wave Festival is sponsored by Philip Morris Companies Inc. This tour has been made possible with the support of Agency for Cultural Affairs, Japan; and Shiseido. 21 HIBIKI Resonance from Far Away I Sizuku: drop The sinking and reflection of a drop II. Utsuri: displacement Most furtive of shadows /II. Garan: empty space Air is like water, calm and quiet IV. Outer limits of the red The body metamorphoses into the object it beholds V. -

Avila Gillian M 2020 Masters.Pdf (12.22Mb)

REPOSITIONING THE OBJECT: EXPLORING PROP USE THROUGH THE FLAMENCO TRILOGY MARIA AVILA A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF FINE ARTS GRADUATE PROGRAM IN DANCE YORK UNIVERSITY TORONTO, ONTARIO APRIL, 2020 © MARIA AVILA, 2020 ii Abstract Reflecting on the creation process of my flamenco trilogy, this thesis explores how one can reposition iconic flamenco objects when devising, creating, and producing three short films: The Fan, The Rose and The Bull. Each film examines personal, historical, and local relationships to iconic flamenco objects, enabled through the collaboration with filmmakers: Audrey Bow, Dayna Szyndrowski, and Clint Mazo. iii Dedication I wish to dedicate this thesis to my mother Pat Smith. An inspirational teacher, artist, arts enthusiast, and the most wonderful mother a daughter could ask for. Miss you. iv Acknowledgements The journey to complete my MFA would not have been possible without the support of many individuals. Thank you to my collaborators Audrey Bow, Dayna Szyndrowski, Clint Mazo, Michael Rush, Sydney Cochrane, Bonnie Takahashi, Josephine Casadei, Verna Lee, Adya Della Vella, and Gerardo Avila for contributing your time and your talents. Thank you to my friends and family, you indeed made this all possible. Thank you to Connie Doucette, Adya Della Vella and Gerardo Avila, for your unconditional support. To my love Clint for risking it all and taking this journey with me. Thank you to my welcoming and encouraging classmates Emilio Colalillo, Raine Madison, Natasha Powell, Lisa Brkich, Christine Brkich, Patricia Allison, and Kari Pederson. Thank you to my editor Nadine Ryan for your dedication, enthusiasm and critical eye. -

Here Has Been a Substantial Re-Engagement with Ibsen Due to Social Progress in China

2019 IFTR CONFERENCE SCHEDULE DAY 1 MONDAY JULY 8 WG 1 DAY 1 MONDAY July 8 9:00-10:30 WG1 SAMUEL BECKETT WORKING GROUP ROOM 204 Chair: Trish McTighe, University of Birmingham 9:00-10:00 General discussion 10:00-11:00 Yoshiko Takebe, Shujitsu University Translating Beckett in Japanese Urbanism and Landscape This paper aims to analyze how Beckett’s drama especially Happy Days is translated within the context of Japanese urbanism and landscape. According to Routledge Encyclopedia of Translation Studies, “shifts are seen as required, indispensable changes at specific semiotic levels, with regard to specific aspects of the source text” (Baker 270) and “changes at a certain semiotic level with respect to a certain aspect of the source text benefit the invariance at other levels and with respect to other aspects” (ibid.). This paper challenges to disclose the concept of urbanism and ruralism that lies in Beckett‘s original text through the lens of site-specific art demonstrated in contemporary Japan. Translating Samuel Beckett’s drama in a different environment and landscape hinges on the effectiveness of the relationship between the movable and the unmovable. The shift from Act I into Act II in Beckett’s Happy Days gives shape to the heroine’s urbanism and ruralism. In other words, Winnie, who is accustomed to being surrounded by urban materialism in Act I, is embedded up to her neck and overpowered by the rural area in Act II. This symbolical shift experienced by Winnie in the play is aesthetically translated both at an urban theatre and at a cave-like theatre in Japan. -

Mission Issue

free The San Francisco Arts Quarterly A Free Publication Dedicated to the SArtistic CommunityFAQ i 3 MISSION ISSUE - Bay Area Arts Calendar Oct. Nov. Dec. Jan - Southern Exposure - Galeria de la Raza - Ratio 3 Gallery - Hamburger Eyes - Oakland Museum - Headlands - Art Practical 6)$,B6)B$UWVB4XDUWHUO\BILQDOLQGG 30 Saturday October 16, 1-6pm Visit www.yerbabuena.org/gallerywalk for more details 111 Minna Gallery Chandler Fine Art SF Camerawork 111 Minna Street - 415/974-1719 170 Minna Street - 415/546-1113 657 Mission Street, 2nd Floor- www.111minnagallery.com www.chandlersf.com 415/512-2020 12 Gallagher Lane Crown Point Press www.sfcamerawork.org 12 Gallagher Lane - 415/896-5700 20 Hawthorne Street - 415/974-6273 UC Berkeley Extension www.12gallagherlane.com www.crownpoint.com 95 3rd Street - 415/284-1081 871 Fine Arts Fivepoints Arthouse www.extension.berkeley.edu/art/gallery.html 20 Hawthorne Street, Lower Level - 72 Tehama Street - 415/989-1166 Visual Aid 415/543-5155 fivepointsarthouse.com 57 Post Street, Suite 905 - 415/777-8242 www.artbook.com/871store Modernism www.visualaid.org The Artists Alley 685 Market Street- 415/541-0461 PAK Gallery 863 Mission Street - 415/522-2440 www.modernisminc.com 425 Second Street , Suite 250 - 818/203-8765 www.theartistsalley.com RayKo Photo Center www.pakink.com Catherine Clark Gallery 428 3rd Street - 415/495-3773 150 Minna Street - 415/399-1439 raykophoto.com www.cclarkgallery.com Galleries are open throughout the year. Yerba Buena Gallery Walks occur twice a year and fall. The Yerba Buena Alliance supports the Yerba Buena Nieghborhood by strengthening partnerships, providing critical neighborhood-wide leadership and infrastructure, serving as an information source and forum for the area’s diverse residents, businesses, and visitiors, and promoting the area as a destination. -

Wcord Archives

Washington University School of Medicine Digital Commons@Becker Washington University Record Washington University Publications 10-15-1987 Washington University Record, October 15, 1987 Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.wustl.edu/record Recommended Citation "Washington University Record, October 15, 1987" (1987). Washington University Record. Book 423. http://digitalcommons.wustl.edu/record/423 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Washington University Publications at Digital Commons@Becker. It has been accepted for inclusion in Washington University Record by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons@Becker. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ft^ sf VvkiiftLs tevuiit? nrT i c ,Q7 yOASH'O&roU (jO/vers/-/-y Mo&raiMuditmJ UiraryL1kr«rv ULI A3 0/ Indexed ARCHIVES jg Washington Z*3WASHINGTON' ■ UNIVERSITY' IN -ST- LOUS WCORD Vol. 12 No. 8/Oct. 15, 1987 NIH centennial celebration features Nobel winners This year the National Institutes of Health (NIH) is commemorating its 100th birthday and in honor of the occasion has selected Washington University as a centennial celebration site. The celebration, open to faculty, staff and students, will take place Fri- day, Oct. 23, in the Carl V. Moore Auditorium at the School of Medi- cine. The theme for the celebration is "Biomedical Research: Key to the Nation's Health." A scientific program will be of- fered beginning at 8:45 a.m. It will be moderated by Nobel Prize winner Daniel Nathans, M.D., university pro- fessor of molecular biology and ge- netics and senior investigator of the Howard Hughes Medical Institute at Johns Hopkins University. -

MOVE YOUR TOWN Am Welttanztag 29. April 2018

MOVE YOUR TOWN am Welttanztag 29. April 2018 SHOWS NEUES RATHAUS / Zentralhalle // 11 Uhr bis 18.30 Uhr 11 Uhr bis 12.15 Uhr 11.00 Uhr Eröffnung mit OB Stefan Schostok Tanzvielfalt aus der Südstadt Move & Style Dance Academy Eine fantastische Tanzshow mit Hip Hop, Breakdance, Contemporary, Dancehall, Slow Jams und Modern Jazz Rollitanzsportgruppe TSC Hannover Die Kombipaare, bestehend aus Rollstuhltänzer/in und Fußgänger/in, zeigen ihr Können im Bereich Standard- und Lateintanz sowie in einer gemeinsam getanzten Formation. Rollstuhl und Tanzbegeisterung schließen sich nicht aus. Früher oder später Barbara von Knobelsdorff und Christian Herrmann Bodypercussion-Performance mit Tanz und Gesang 12.15 Uhr bis 13.45 Uhr Klassischer indischer Tanz und Bollywood Radha Grundey Rhythmische Fußarbeit, ausladenden Gesten und feine Mimik zeichnen indischen Tanz aus. Kombiniert mit Anregungen aus Musikstilen der westlichen Welt ergibt das den typischen Bollywood-Style. Japanischer Tribal Fusion Maiko Traditioneller japanischer Tanz im Stil der Maikos (Lern-Geishas) aus Kioto und Tribal Fusion Orientalische Tänze Salwa & Serenity Orientalisches Tanz-Duo mit Oriental Fantasy Tänzen Salsa-Show Salsa del Alma Salsa, Merengue und Bachata – Tanz als Quelle der Lebensfreude 13.45 Uhr bis 15 Uhr Talking Through Dance NVC Dance Ensemble Tanzvielfalt als Botschaft ohne Worte Tribal Style Bellydance Calaneya Dance Academy 1 Man nehme eine Prise Flamenco, einen Hauch indischen Tanz, einen Schwung orientalischen Tanz und jede Menge Spaß: Fertig ist American Tribal Style! 15 Uhr bis 16 Uhr Volkstänze und Clogging Volkstanzgruppe von Loek Grobben und die Clogging Turtles aus dem Freizeitheim Vahrenwald Clogging ist Steptanz nach Ansage Best of Orient Gruppe Almaseya Traditioneller ägyptischer Bauchtanz kombiniert mit modernen, poppigen Elementen Hips'n Wheels 1. -

Talk Abstract

Robots get better, people don't. Godfried-Willem Raes Three events, all in 1958, have marked my early childhood, as I came to discover not so long ago: 1.- The Philips Pavilion at the world exhibition in Brussels, where I was submerged night after night in the visual and sonic environment of Varese's 'Poème Electronique'. 2.- The launch of the Russian 'Sputnik', the spark that lit my deep fascination for the world of electronics. 3.- My enrolment at age six, in the Ghent Conservatory and the two pianos we had at home which I refused to play unless the mechanism was disclosed. Ten years later, the magic year 1968, these components one way or another came together as the Logos group was founded. We wrote a manifest wherein we stated to refuse to play old music, to work on new sounds and instruments and to experiment with alternative methods of music making. Although not so obvious for musicians these days, it appeared to be clear that there was no great -if any- future for musicianship in the very traditional sense. The reasons are manifold: first of all, why would the collection of instruments thought at our conservatories be suitable for expressing musical needs of our time? These instruments all have been developed in the 18th and 19th century and therefore are perfectly suited for playing the music of that past. There is no ground for a claim that they would be suitable for music of our time. Moreover, learning to play these instruments well, is a tedious job and the overall quality of players is going down at a steady pace. -

Meguri Teeming Sea, Tranquil Land

Meguri Teeming Sea, Tranquil Land Sankai Juku Ushio Amagatsu Choreography, Concept, and Direction Friday Evening, October 25, 2019 at 8:00 Saturday Evening, October 26, 2019 at 8:00 Power Center Ann Arbor 15th and 16th Performances of the 141st Annual Season 29th Annual Dance Series This weekend’s performances are supported by Level X Talent. Special thanks to Amy Chavasse, Anita Gonzalez, Katie Gunning, Grace Lehman and the Ann Arbor Y, and the U-M Department of Dance for their participation in events surrounding this weekend’s performances. Sankai Juku’s 2019 North American tour is supported by the Agency for Cultural Affairs, Government of Japan through the Japan Arts Council and Shiseido Co., Ltd. Sankai Juku appears by arrangement with Pomegranate Arts. In consideration of the artists and the audience, please refrain from the use of electronic devices during the performance. The photography, sound recording, or videotaping of this performance is prohibited. PROGRAM Meguri: Teeming Sea, Tranquil Land I. The Call from the Distance II. Transformation on the Sea Bottom III. Two Surfaces I V. Premonition – Quietude – Tremblings V. Forest of fossils VI. Weavings VII. Return This evening’s performance is approximately one hour and 30 minutes in duration and is performed without intermission. 3 CREATIVE TEAM Choreography, Concept, and Artistic Direction / Ushio Amagatsu Music / Takashi Kako, YAS-KAZ, Yoichiro Yoshikawa Dancers / Semimaru, Toru Iwashita, Sho Takeuchi, Akihito Ichihara, Dai Matsuoka, Norihito Ishii, Shunsuke Momoki, Taiki Iwamoto