Bibliography James Baldwin

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sonny's Blues Study Guide

Sonny's Blues Study Guide © 2018 eNotes.com, Inc. or its Licensors. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. No part of this work covered by the copyright hereon may be reproduced or used in any form or by any means graphic, electronic, or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, taping, Web distribution or information storage retrieval systems without the written permission of the publisher. Summary The narrator, a teacher in Harlem, has escaped the ghetto, creating a stable and secure life for himself despite the destructive pressures that he sees destroying so many young blacks. He sees African American adolescents discovering the limits placed on them by a racist society at the very moment when they are discovering their abilities. He tells the story of his relationship with his younger brother, Sonny. That relationship has moved through phases of separation and return. After their parents’ deaths, he tried and failed to be a father to Sonny. For a while, he believed that Sonny had succumbed to the destructive influences of Harlem life. Finally, however, they achieved a reconciliation in which the narrator came to understand the value and the importance of Sonny’s need to be a jazz pianist. The story opens with a crisis in their relationship. The narrator reads in the newspaper that Sonny was taken into custody in a drug raid. He learns that Sonny is addicted to heroin and that he will be sent to a treatment facility to be “cured.” Unable to believe that his gentle and quiet brother could have so abused himself, the narrator cannot reopen communication with Sonny until a second crisis occurs, the death of his daughter from polio. -

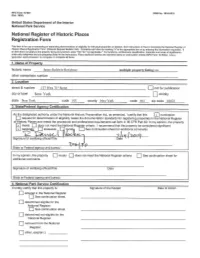

James Baldwin Residence Multiple Property Listing: No Other Names/Site Number 2

NPS Form 10-900 OMB No. 1024-0018 (Oct. 1990) United States Department of the Interior National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Registration Form This form is for use in nominating or requesting determinations of eligibility for individual properties or districts. See instructions in How to Complete the National Register of Historic Places Registration Form (National Register Bulletin 16A). Complete each item by marking "x" in the appropriate box or by entering the information requested. If an item does not apply to the property being documented, enter "N/A" for "not applicable." For functions, architectural classification, materials and areas of significance, enter only categories and subcategories listed in the instructions. Place additional entries and narrative items on continuation sheets (NPS Form 10-900a). Use a typewriter, word processor, or computer, to complete all items. 1. Name of Property historic name James Baldwin Residence multiple property listing: no other names/site number 2. Location street & number 137 West 71st Street not for publication city or town New York vicinity state New York code NY county New York code 061 zip code 10023 3. State/Federal Agency Certification As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act, as amended, I certify that this x nomination request for determination of eligibility meets the documentation standards for registering properties in the National Register of Historic Places and meets the procedural and professional requirements set forth in 36 CFR Part 60. In my opinion, the property x meets does not meet the National Register criteria. I recommend that this property be considered significant x nationally statewide locally. -

Baldwin and Identity ...8

JUST ABOVE MY HEAD: JAMES BALDWIN’S CULTURAL IDENTITY POLITICS By MAURICE ANTHONY EVERS A THESIS PRESENTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF OF MASTER OF ARTS UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA 2015 © 2015 Maurice Anthony Evers To my parents ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I would like to thank my parents, family, and everyone who supported me intellectually and emotionally during the writing of this thesis. A special thank you to Dr. Mark Reid, who has been most influential in my thinking, reading, and writing over the past two years and especially, in this thesis, and to Dr. Laurie Gries, who was instrumental in the writing of this project. 4 TABLE OF CONTENTS page ACKNOWLEDGMENTS .................................................................................................. 4 ABSTRACT ..................................................................................................................... 6 CHAPTER 1 INTRODUCTION: BALDWIN AND IDENTITY .......................................................... 8 2 BALDWIN’S CHARACTERS AND THE ARTIST’S BURDEN ................................. 30 3 A (RE)READING OF BALDWIN ............................................................................. 38 LIST OF REFERENCES ............................................................................................... 43 BIOGRAPHICAL SKETCH ............................................................................................ 45 5 Abstract of Thesis Presented to the Graduate School of -

The Cage of Reality: Nuancing Processes of Identity in James Baldwin's Fiction

The Cage of Reality Nuancing Processes of Identity in James Baldwin’s Fiction Regine Lundevall Bergersen A Thesis Presented to the Department of Literature, Area Studies, and European Languages UNIVERSITY OF OSLO In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Master’s of Arts Degree SPRING 2017 I II The Cage of Reality Nuancing Processes of Identity in James Baldwin’s Fiction Regine Lundevall Bergersen III Copyright Regine Lundevall Bergersen 2017 The Cage of Reality: Nuancing Processes of Identity in James Baldwin’s Fiction Regine Lundevall Bergersen http://www.duo.uio.no Trykk: Reprosentralen, Universitetet i Oslo IV Abstract This thesis explores issues and processes of identity in three pieces of James Baldwin’s fiction: “Going to Meet the Man” (1965), Giovanni’s Room (1956), and Another Country (1962). The point of departure is Baldwin’s concept of “the cage of reality,” a term used to describe the ways in which society traps the individual in a mold of assigned identity, and from which one cannot escape, but can hope to be free from through acknowledgement. The processes of acknowledging or ignoring the cage of reality is what this thesis explores in central characters in these three works, and this study finds that American society is riddled with a trait Baldwin calls “preservation of innocence,” translatable to a willful ignorance of the cage of reality, which explains the persistence of harmful identity norms. The key to overcoming the cage of reality is, according to Baldwin, to take responsibility, and accept that all individuals exist in a “web of ambiguity.” This thesis uses critical race theory and some psychoanalytical approaches to the short story “Going to Meet the Man,” and a selection of existentialist terms in the readings of Giovanni’s Room and Another Country. -

James Baldwin

Wexner Center for the Arts School Programs Resources I Am Not Your Negro BASED ON: Remember this House, uncompleted book by James Baldwin DIRECTOR: Raoul Peck “I love America more than any other country in the world and, exactly for this reason, I insist on the right to criticize her perpetually.” - James Baldwin [Baldwin’s] “prose is laser sharp. His onslaught is massive and leaves no room for response. Every sentence is an immediate cocked grenade. You pick it up, then realize that it is too late. It just blows up in your face. And yet he still managed to stay human, tender, accessible.” – Director, Raoul Peck 1 ABOUT THE FILM: • In 1979, James Baldwin wrote a letter to his literary agent describing his next project, Remember This House. The book was to be a revolutionary, personal account of the lives and successive assassinations of three of his close friends—Medgar Evers, Malcolm X and Martin Luther King, Jr. At the time of Baldwin’s death in 1987, he left behind only thirty completed pages of his manuscript. • Raoul Peck, the director, originally envisioned a narrative film and documentary, but instead created an essay about images, their origins, discourse, and Baldwin’s words. The final product envisions the book Baldwin never finished, connecting the past of the Civil Rights movement to the present of #BlackLivesMatter. • The film is primarily visual and musical. I Am Not Your Negro uses archival images from private and public photos; film clips, Hollywood classics, documentaries, film and TV interviews, popular TV shows, TV debates, public debates and contemporary images. -

Study Guide Contents Director of Community Engagement & Education Joann Yarrow (315) 443-8603

Study Guide Contents Director of Community Engagement & Education Joann Yarrow (315) 443-8603 3.) Production Information Associate Director of Education 4.) Letter from Community Engagement and Education Team Kate Laissle (315) 442-7755 5.) Educational Outreach at Syracuse Stage 6.) Synopsis Group Sales & Student Matinees Tracey White 7.) Meet the Playwright (315) 443-9844 8.) Meet the Director 9.) James Baldwin Box Office (315) 443-3275 11.) Evolution of LaGuardia Airport 12.) Harlem, 1940s To Donate To Our Education Programs: 13.) Paris, 1940s Wendy Rhodes Director of Development 14.) Baldwin and the Civil Rights Movement 315-443-3931 15.) People to Know [email protected] 16.) Baldwin’s Work and Speeches Research and text by J.R. Pierce 17.) Questions for Discussion Designed by Kate Laissle 18.) Elements of Drama 19.) Elements of Design 20.) Sources 2 | SYRACUSE STAGE EDUCATION Dear Educator, The best way of learning is learning while you’re having fun. Live theatre provides the opportunity for us to connect with more than just our own story, it allows us to find ourselves in other people’s lives and grow beyond our own boundaries. While times are different, we still are excited to share with you new theatrical pieces through pre-recorded means. We’re the only species on the planet who makes stories. It is the stories that we leave behind that define us. Giving students the power to watch stories and create their own is part of our lasting impact on the world. And the stories we choose to hear and learn from now are even more vital. -

Read Ebook {PDF EPUB} a Rap on Race by James Baldwin a Rap on Race by James Baldwin

Read Ebook {PDF EPUB} A Rap on Race by James Baldwin A Rap on Race by James Baldwin. Completing the CAPTCHA proves you are a human and gives you temporary access to the web property. What can I do to prevent this in the future? If you are on a personal connection, like at home, you can run an anti-virus scan on your device to make sure it is not infected with malware. If you are at an office or shared network, you can ask the network administrator to run a scan across the network looking for misconfigured or infected devices. Another way to prevent getting this page in the future is to use Privacy Pass. You may need to download version 2.0 now from the Chrome Web Store. Cloudflare Ray ID: 656444a05cd416af • Your IP : 188.246.226.140 • Performance & security by Cloudflare. james baldwin and margaret mead – a rap on race (1971) “In honor of the release of James Baldwin: I Am Not Your Negro documentary, we’ve decided to share the rare audio version of the classic conversation between Margaret Mead and James Baldwin from 1971. Long out of print, original LP sells for 3 figures. Courtesy The Charles Woods Collection. For educational purposes. No rights given or implied. Feel free to comment/share/subscribe. Share original link whenever possible.” Download Margaret Mead & James Baldwin - A Rap On Race (1971) MP3. Lalotoso ma faʻalogo Margaret Mead & James Baldwin - A Rap On Race (1971) MP3 at docker-sample.dokku.a17.io leai se tapulaʻa Kiliki download e download ai le pese Margaret Mead & James Baldwin - A Rap On Race (1971) pe e mafai ona e taina lenei pese mo se vaʻaiga mamao. -

I Am Not Your Negro

[DATE] THE LIBRARY OF CONGRESS [Company address] I Am Not Your Negro Curriculum Guide “Freedom is not something that anybody can be given. Freedom is something people take, and people are as free as they want to be” ― James Baldwin “I love America more than any other country in the world and, exactly for this reason, I insist on the right to criticize her perpetually.” ― James Baldwin “To be a Negro in this country and to be relatively conscious is to be in a rage almost all the time.” ― James Baldwin “I remember when the ex-Attorney General, Mr. Robert Kennedy, said it was conceivable that in 40 years in America we might have a Negro President. That sounded like a very emancipated statement to white people. They were not in Harlem when this statement was first heard. They did not hear the laughter and bitterness and scorn with which this statement was greeted. From the point of view of the man in the Harlem barber shop, Bobby Kennedy only got here yesterday and now he is already on his way to the Presidency. We were here for 400 years and now he tells us that maybe in 40 years, if you are good, we may let you become President.” ― James Baldwin Page | 2 Table of Contents A Message from the Director 4 Who Was James Baldwin? 8 James Baldwin the Activist: The Pen Is Mightier 9 Medgar, Malcolm, Martin 15 The Influence of Educators, Arts, and Culture on James Baldwin 23 Baldwin and the Importance of Letters 25 France as a Haven for African Americans 29 Major Organizations during the Civil Rights Movement 33 World Events during the Life of James Baldwin 38 Where Do We Go from Here? 41 How the Film, “I Am Not Your Negro” Can be used in the Classroom 45 Indexed Lesson Plans 48 Video Lesson Prompt Resources 50 Lesson Templates 52 Page | 3 A MESSAGE FROM THE DIRECTOR – RAOUL PECK I started reading James Baldwin when I was a 15-year-old boy searching for rational explanations to the contradictions I was confronting in my already nomadic life, which took me from Haiti to Congo to France to Germany and to the United States of America. -

Kairotic Time, Recognition, and Freedom in James Baldwin's Go

i i i i ESSAY Kairotic Time, Recognition, and Freedom in James Baldwin’s Go Tell It on the Mountain Robert Z. Birdwell Tulane University Abstract Go Tell It on the Mountain sheds light on James Baldwin’s response to his Pente- costal religious inheritance. Baldwin writes protagonist John Grimes’s experience of “salvation” as an act of his own break with his past and the inauguration of a new vocation as authorial witness of his times. This break is premised on the experience of kairos, a form of time that was derived from Baldwin’s experience of Pentecostalism. Through John Grimes’s experience, Baldwin represents a break with the past that begins with the kairotic moment and progresses through the beginnings of self-love and the possibility of freedom enabled by this love. This essay contributes a new perspective on discussions of Baldwin’s representation of time and his relationship to Christianity. Keywords: Go Tell It on the Mountain, kairos, recognition, freedom James Baldwin said that Go Tell It on the Mountain “is the book I had to write if I was ever going to write anything else ::: I had to deal with what hurt most. I had to deal, above all, with my father.”1 Baldwin’s own vocation as a writer was at stake in the writing of this autobiographical rst novel, one Sabbath in the life of John Grimes, a 14-year-old who is apparently destined for the ministry in Pentecostal Christianity but who has so far resisted undergoing the moment of “salvation.” Go Tell It on the Mountain tells the story of John’s experience of salvation, yet the result of this experience is ambiguous: it is not clear whether the novel concludes with a John Grimes who is destined to become a preacher, or a John Grimes who is destined to do otherwise. -

James Baldwin Daryl Cumber Dance University of Richmond, [email protected]

University of Richmond UR Scholarship Repository English Faculty Publications English 1978 James Baldwin Daryl Cumber Dance University of Richmond, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.richmond.edu/english-faculty-publications Part of the African American Studies Commons, Caribbean Languages and Societies Commons, and the Literature in English, North America, Ethnic and Cultural Minority Commons Recommended Citation Dance, Daryl Cumber. "James Baldwin." In Black American Writers: Bibliographical Essays, edited by M. Thomas Inge, Maurice Duke, and Jackson R. Bryer, 73-120. Vol. 2. New York: St. Martin's Press, 1978. This Book Chapter is brought to you for free and open access by the English at UR Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in English Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of UR Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. JAMES BALDWIN DARYL DANCE James Baldwin is one of America's best known and most controversial writers. If there is some figurative truth in his declarations "Nobody Knows My Name" and "No Name in the Street," on a realistic level practically everyone knows his name, from people on the street to scholars in the most prestigious universities-and they all respond to him. Those responses are as diverse and as antithetical as the respon dents. Indeed, there is little unanimity in the criticism of James Bald win: some view him as a prophet preaching love and salvation, others as a soothsayer forecasting death and destruction; some see him as a civil-rights advocate writing protest literature, others as an artist imagi natively portraying the plight of the black American or the alienated man. -

I Am Not Your Negro James Baldwin

BIBLIOTECA TECLA SALA November 21, 2019 I Am Not Your Negro James Baldwin « You never had to look at me. I had to look at you. I know more about you than you know about me. Not everything that is faced can Contents: Introduction 1 be changed; but nothing can Brief Author 2-3 Biography From Remember 4-5 be changed until it is faced. This House to I Am Not Your Negro: An Unfinished Book » Becomes A Successful Movie James Baldwin and 6- Margaret Mead on 10 Indentity, Race, the Immigrant Experience, and Why the “Melting Pot” Is a Problematic Metaphor Notes 11 Page 2 Brief Author Biography James Arthur Baldwin was born minister for three years at the In 1944 he met author Richard on August 2, 1924 in New York Fireside Pentecostal Assembly, Wright, who helped him to land City’s Harlem and was raised but gradually lost his desire to the 1945 Eugene F. Saxton under very trying circumstances. preach as he began to question fellowship. Despite the financial As is the case with many writers, Christian tenets. freedom the fellowship provided, Baldwin’s upbringing is reflected in Baldwin was unable to complete his writings, especially in Go Tell It Shortly after he graduated from his novel that year. He found the on the Mountain. high school in 1942, Baldwin was social tenor of the United States compelled to find work in order increasingly stifling even though Baldwin’s stepfather, an to help support his brothers and such prestigious periodicals as evangelical preacher, struggled to sisters; mental instability had the Nation, New support a large family and incapacitated his stepfather. -

James Baldwin

James Baldwin Among African-American writers and social leaders of the 20th century, perhaps none have articulated the painful legacy of slavery and racism in modern America better than James Baldwin. An internationally acclaimed author of essays, novels, plays, and poetry, Baldwin is best known for his eloquent and finely crafted essays and his autobiographical novel Go Tell It on the Mountain (1953). Baldwin's writings reshaped the language of racial protest during the 1950s and 1960s and have continued to inspire generations of black authors and activists. James Arthur Baldwin was born on August 2, 1924, to Berdis Emma Jones, who delivered him out of wedlock at Harlem Hospital in New York. Baldwin's mother later married David Baldwin, a factory worker and puritanical lay preacher in a storefront church in Harlem, whom Baldwin described as "certainly the most bitter man I have ever met." Baldwin's childhood in Harlem was characterized by poverty, racism, and resentment by his stepfather, whose physical and psychological abuse shattered the boy's self-esteem. As a student at Public School 24 in Harlem, Baldwin soon impressed his teachers with his intelligence, and they encouraged him to read and write. He began to frequent the local public library, eventually claiming to have read every one of its books, and developed a passion for film and drama. Baldwin attended Frederick Douglass Junior High School and received further encouragement from poet Countee Cullen, a French teacher at the school and founder of its literary club. Baldwin edited the school newspaper, the Douglass Pilot, to which he also contributed a short story and several essays.