A Dialogue Explores Problems Facing Americans, Black and White, As Well As Troubles Besetting the World

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

James Baldwin As a Writer of Short Fiction: an Evaluation

JAMES BALDWIN AS A WRITER OF SHORT FICTION: AN EVALUATION dayton G. Holloway A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate School of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY December 1975 618208 ii Abstract Well known as a brilliant essayist and gifted novelist, James Baldwin has received little critical attention as short story writer. This dissertation analyzes his short fiction, concentrating on character, theme and technique, with some attention to biographical parallels. The first three chapters establish a background for the analysis and criticism sections. Chapter 1 provides a biographi cal sketch and places each story in relation to Baldwin's novels, plays and essays. Chapter 2 summarizes the author's theory of fiction and presents his image of the creative writer. Chapter 3 surveys critical opinions to determine Baldwin's reputation as an artist. The survey concludes that the author is a superior essayist, but is uneven as a creator of imaginative literature. Critics, in general, have not judged Baldwin's fiction by his own aesthetic criteria. The next three chapters provide a close thematic analysis of Baldwin's short stories. Chapter 4 discusses "The Rockpile," "The Outing," "Roy's Wound," and "The Death of the Prophet," a Bi 1 dungsroman about the tension and ambivalence between a black minister-father and his sons. In contrast, Chapter 5 treats the theme of affection between white fathers and sons and their ambivalence toward social outcasts—the white homosexual and black demonstrator—in "The Man Child" and "Going to Meet the Man." Chapter 6 explores the theme of escape from the black community and the conseauences of estrangement and identity crises in "Previous Condition," "Sonny's Blues," "Come Out the Wilderness" and "This Morning, This Evening, So Soon." The last chapter attempts to apply Baldwin's aesthetic principles to his short fiction. -

Death and Dying in 20Th Century African American Literature Chayah Amayala Stoneberg-Cooper University of South Carolina - Columbia

University of South Carolina Scholar Commons Theses and Dissertations 1-1-2013 Going Hard, Going Easy, Going Home: Death and Dying in 20th Century African American Literature Chayah Amayala Stoneberg-Cooper University of South Carolina - Columbia Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/etd Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Stoneberg-Cooper, C. A.(2013). Going Hard, Going Easy, Going Home: Death and Dying in 20th Century African American Literature. (Doctoral dissertation). Retrieved from https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/etd/2440 This Open Access Dissertation is brought to you by Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. GOING HARD, GOING EASY, GOING HOME: DEATH AND DYING IN TWENTIETH-CENTURY AFRICAN AMERICAN LITERATURE by Chayah Stoneberg-Cooper Bachelor of Arts University of Oregon, 2001 Master of Arts University of California, San Diego, 2003 Master of Arts New York University, 2005 Master of Social Work University of South Carolina, 2011 Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in English Literature College of Arts and Sciences University of South Carolina 2013 Accepted by: Qiana Whitted, Major Professor Kwame Dawes, Committee Member Folashade Alao, Committee Member Bobby Donaldson, Committee Member Lacy Ford, Vice Provost and Dean of Graduate Studies © Copyright by Chayah Stoneberg-Cooper, 2013 All Rights Reserved. ii DEDICATION This work is dedicated to my family and friends, often one and the same, both living and dead, whose successes and struggles have made the completion of this work possible. -

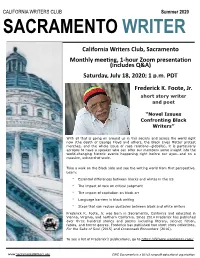

CWC Newsletter Summer (July:Aug) 2020

CALIFORNIA WRITERS CLUB Summer 2020 SACRAMENTO WRITER California Writers Club, Sacramento Monthly mee7ng, 1-hour Zoom presenta7on (includes Q&A) Saturday, July 18, 2020; 1 p.m. PDT Frederick K. Foote, Jr. short story writer and poet “Novel Issues Confronting Black Writers” With all that is going on around us in this society and across the world right now (the death of George Floyd and others, the Black Lives Matter protest marches, and the whole issue of race relations--globally), it is particularly apropos to have a speaker who can offer our members some insight into the world-changing historic events happening right before our eyes--and on a massive, unheard-of scale. Take a walk on the Black side and see the writing world from that perspective. Learn: • Essential differences between blacks and whites in the US • The impact of race on critical judgment • The impact of capitalism on black art • Language barriers in black writing • Steps that can reduce obstacles between black and white writers Frederick K. Foote, Jr. was born in Sacramento, California and educated in Vienna, Virginia, and northern California. Since 2014 Frederick has published over three hundred stories and poems including literary, science fiction, fables, and horror genres. Frederick has published two short story collections, For the Sake of Soul (2015) and Crossroads Encounters (2016). To see a list of Frederick’s publications, go to https://fkfoote.wordpress.com/ www.SacramentoWriters.org CWC Sacramento is a 501c3 nonprofit educational organization First Friday Networking Zoom July 3, 2020 at 10 a.m. Mini-Crowdsource Opportunity The CWC First Friday Zoom network meeting will be an opportunity to bring your most intractable, gruesome, horrendous, writing challenge to our forum of compassionate writers for solution. -

Dystopian America in Revolutionary Road and 'Sonny's Blues'

Dystopian America in Revolutionary Road and ‘Sonny’s Blues’ Kate Garrow America as a nation is often associated with values of freedom, nationalism, and the optimistic pursuit of dreams. However, in Revolutionary Road1 by Richard Yates and ‘Sonny’s Blues’2 by James Baldwin, the authors display a pessimistic view of America as a land characterised by suffering and entrapment, supporting the view of literary critic Leslie Fiedler that American literature is one ‘of darkness and the grotesque’.3 Through the contrasting communities of white middle-class suburbia and Harlem, the authors depict a dystopian America, where characters are stripped of their agency and forced to rely on illusions, false appearances, or escape in order to survive. Both ‘Sonny’s Blues’ and Revolutionary Road confirm that despite America’s appearance as ‘a land of light and affirmation’,4 it hides a much darker reality. Both Yates and Baldwin use characteristics of dystopian literature to create their respective American societies. Revolutionary Road is set in a white middle-class suburban society fuelled by materialism and false appearances. In particular, the community demands conformity. Men must succumb to a bland office job that ‘would swallow them up’5 and 1 R. Yates, Revolutionary Road, London, Random House, 2007. 2 A. Baldwin, ‘Sonny’s Blues’, in Going to Meet the Man, Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group, 2013. 3 L. Fiedler, Love and Death in the American Novel, Stein and Day, 1960, p. 29. 4 Fiedler, p. 29. 5 Yates, Revolutionary Road, p. 119. Burgmann Journal VI (2017) women must accept the feminine role as submissive housewife. -

The Poetry of Rita Dove

University of New Hampshire University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository Doctoral Dissertations Student Scholarship Winter 1999 Language's "bliss of unfolding" in and through history, autobiography and myth: The poetry of Rita Dove Carol Keyes University of New Hampshire, Durham Follow this and additional works at: https://scholars.unh.edu/dissertation Recommended Citation Keyes, Carol, "Language's "bliss of unfolding" in and through history, autobiography and myth: The poetry of Rita Dove" (1999). Doctoral Dissertations. 2107. https://scholars.unh.edu/dissertation/2107 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Scholarship at University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized administrator of University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMi films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. -

Perched in Potential: Mobility, Liminality, and Blues Aesthetics

PERCHED IN POTENTIAL: MOBILITY, LIMINALITY, AND BLUES AESTHETICS IN THE WRITINGS OF JAMES BALDWIN by TAREVA LESELLE JOHNSON (Under the Direction of Valerie Babb) ABSTRACT James Baldwin’s mobility and appreciation for African American musical traditions play an integral part in the writer’s crossing of genre and subgenre, his unique style, and his preoccupation with repeated themes. The interplay of music and shifting space in Baldwin’s life and texts create liminal spaces for Baldwin and readers to enter. In these spaces, clearer understandings of the importance of exteriority and interiority, simultaneously, are achieved. This in-betweenness is a place of potential and power. Baldwin’s writing uses this power to chronicle his own growing consciousness and to create, with his collective works, and through them, Baldwininan literary theory that applies to his own works’ use of liminality, the blues and travel. One is able to overhear Baldwin speaking to himself via his texts at multiple points in his nearly forty-year career. INDEX WORDS: James Baldwin, Transatlantic, Liminal, Mobility, Blues, African American, Go Tell It on the Mountain, The Amen Corner, Sonny’s Blues, The Uses of the Blues, Paris, Turkey, Exile PERCHED IN POTENTIAL: MOBILITY, LIMINALITY, AND BLUES AESTHETICS IN THE WRITINGS OF JAMES BALDWIN by TAREVA LESELLE JOHNSON B.A., COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY, 2008 A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of The University of Georgia in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree MASTER OF ARTS ATHENS, GEORGIA 2012 © 2012 Tareva Leselle Johnson All Rights Reserved PERCHED IN POTENTIAL: MOBILITY, LIMINALITY, AND BLUES AESTHETICS IN THE WRITINGS OF JAMES BALDWIN by TAREVA LESELLE JOHNSON Major Professor: Valerie Babb Committee: Cody Marrs Barbara McCaskill Electronic Version Approved: Maureen Grasso Dean of the Graduate School The University of Georgia May 2012 iv DEDICATION I dedicate this project to my brother, Jerome, and everyone else who makes their way back time and time again. -

Going to Meet the Man”: Scripting White Supremacist Eros

Benlloch ENG 390: Final “Going to Meet the Man”: Scripting White Supremacist Eros In order to be utilized, our erotic feelings must be recognized. The need for sharing deep feeling is a human need. But within the european-american tradition, this need is satisfied by certain proscribed erotic comings-together. These occasions are almost always characterized by a simultaneous looking away, a pretense of calling them something else, whether a religion, a fit, mob violence, or even playing doctor. –Audre Lorde, “Uses of the Erotic: The Erotic as Power” (emphasis mine) If we think of “flesh” as a primary narrative, then we mean its seared, divided, ripped-apartness, riveted to the ship’s hole, fallen, or escaped overboard. —Hortense Spillers, “Mama’s Baby, Papa’s Maybe” All attempts to explain the malicious standard operating procedure of the US white supremacy find themselves hamstrung by conceptual inadequacy; it remains describable, but not comprehensible. —Steve Martinot and Jared Sexton, “The Avant-Garde of White Supremacy” Introduction In 1931, Raymond Gunn was burned to death, his still living body dragged to the top of a Maryville, Missouri schoolhouse, bound to the ridgepole by a horde of unmasked local men, and doused in gasoline (Kremer 359). Before the schoolhouse collapsed in a billowing inferno, leaving Raymond’s body to disintegrate in a manner of minutes, spectators confirmed the presence of the mob leader, an outsider in a red coat who led the lynch mob and who was ultimately responsible for throwing a flaming piece of paper into the gasoline-soaked building (Kremer 360). Despite the outsider’s eponymous red coat, the identity of the mob leader remains anonymous to history, yet I argue that “the man in the red coat,” far from being ‘unknown,’ is an all too overt and present amalgam for the civil roots of the eroticization of the color line in the United States. -

James Baldwin and James Cone: God, Man, and the Redeeming Relationship

Obsculta Volume 8 Issue 1 Article 3 5-22-2015 James Baldwin and James Cone: God, Man, and the Redeeming Relationship Rea McDonnell S.S.N.D. College of Saint Benedict/Saint John's University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.csbsju.edu/obsculta Part of the Christianity Commons, Race and Ethnicity Commons, and the Religious Thought, Theology and Philosophy of Religion Commons ISSN: 2472-2596 (print) ISSN: 2472-260X (online) Recommended Citation McDonnell, Rea S.S.N.D.. 2015. James Baldwin and James Cone: God, Man, and the Redeeming Relationship. Obsculta 8, (1) : 13-54. https://digitalcommons.csbsju.edu/obsculta/vol8/iss1/3. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@CSB/SJU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Obsculta by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@CSB/SJU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. OBSCVLTA J AMES B ALDWIN AND J AMES C ONE : G OD , M AN , AND THE R EDEEMIN G R ELATIONSHI P Sister Rea McDonnell, S.S.N.D. (1972) Abstract - Pope Francis calls us to live among the wounded and marginalized, letting them heal us and free us. How very cur- rent that makes this article, written as a Master’s thesis in 1972. Apart from anachronisms such as writing about God as “man” (instead of men/women), about redeeming (when I meant sav- ing), what is so apropos is the good news proclaimed by both James Cone and James Baldwin. James Cone wrote ground- breaking books on liberation theology. James Baldwin, as an author, expresses Black theology through his characters. -

The Biblical Foundation of James Baldwin's "Sonny's Blues" James Tackach Roger Williams University, [email protected]

Roger Williams University DOCS@RWU Feinstein College of Arts & Sciences Faculty Papers Feinstein College of Arts and Sciences 12-23-2007 The biblical foundation of James Baldwin's "Sonny's Blues" James Tackach Roger Williams University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://docs.rwu.edu/fcas_fp Part of the Literature in English, North America Commons Recommended Citation Tackach, James. 2007. "The iB blical Foundation of James Baldwin’s ‘Sonny’s Blues'." Renascence: Essays on Values in Literature 59 (2). This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Feinstein College of Arts and Sciences at DOCS@RWU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Feinstein College of Arts & Sciences Faculty Papers by an authorized administrator of DOCS@RWU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. James Tackach THE BIBLICAL FOUNDATION OF JAMES BALDWIN'S "SONNY'S BLUES" ONNY'S Blues" is James Baldwin's most anthologized and most critically discussed short story. Most critical analyses of "Sonny's SBlues" have centered on the story's unnamed narrator's identity is- sues (Bieganowski, Reid, Murray) and Baldwin's use of blues /jazz mu- sic within the story (Jones, Sherard, Byerman, Goldman). Surprisingly, few critical discussions of "Sonny's Blues" have focused on the story's religious themes. Robert Reid, in an article devoted mainly to Baldwin's narrator's identity concerns, compares the narrator to the biblical Ishmael and Sonny to Isaac (444-45); Jim Sanderson discusses the role of grace in the story; and Marlene Mosher, in a very short essay, explicates the bibli- cal allusion in the story's final image — the "cup of trembling" glowing and shaking above Sonny's head as he plays the piano (Baldwin, "Sonny's Blues" 141). -

Beauford Delaney & James Baldwin

BEAUFORD DELANEY & JAMES BALDWIN: THROUGH THE UNUSUAL DOOR selected timeline Beauford Delaney 1940 Meets Delaney for the first time 1961 While traveling by boat across 1970 Buys a home at Saint-Paul-de- James Baldwin at the artist’s 181 Greene Street studio. the Mediterranean to Greece, jumps Vence, in the South of France. 1941 Spends Christmas with his fam- overboard in a suicide attempt and is 1971 Travels to London to appear with 1901 Born Knoxville, Tennessee, ily in Knoxville. Appears in Delaney’s rescued by a fisherman. Friends pay poet/activist Nikki Giovanni on the on December 30 to Delia Johnson art for the first time in Dark Rapture for his return to Paris and hospitaliza- television program Soul. At his new Delaney and the Reverend John Samuel (James Baldwin). tion. Second essay collection, Nobody home, he is visited frequently by an Delaney, 815 East Vine Avenue. Knows My Name, published by Dial. 1942 Graduates from DeWitt Clinton increasingly unstable Delaney, who 1919 Father dies on April 30. Rioting Makes first trip to Istanbul, where he High School. sees Baldwin’s home as a refuge. breaks out in August after an African finishes writing his third novel, Another 1972 Publishes No Name in the Street, American man, Maurice Franklin Mays, 1943 Stepfather David Baldwin dies. Country. his fourth book of non-fiction, and is accused of murdering a white woman 1944 Appears in Delaney’s pastel 1962 Moves to 53 Rue Vercingetorix dedicates it to Delaney. in what would later become known as Portrait of James Baldwin. in Montparnasse. -

Black History Month

HERMANN MEMORIAL LIBRARY -- SULLIVAN COUNTY COMMUNITY COLLEGE BLACK HISTORY MONTH SELECTED BIBLIOGRAPHY OF TITLES FROM OUR PRINT COLLECTIONS AND FROM EBRARY The following bibliography is a sampling from our collections of the broad range of work by and about African Americans reflecting their immeasurable importance in our history and culture. It includes reference books, and circulating books.. The bibliography is not a checklist of books on display in the exhibition, but each is intended to complement the other. Many more books than are listed here can be found in our Sullivan Catalog. Full-text articles in magazines, journals and newspapers can be accessed from our Subscription Periodical Databases. A librarian will be glad to show you how to search these tools. Our own paper periodical collections include many titles of especial relevance to Black studies, as well as general interest magazines which cover Black issues. See our separately issued Periodical List. Books by and about Martin Luther King have been published in another bibliography available in this library. Please refer to that bibliography to research this topic. I. REFERENCE BOOKS African American lives. Edited by Henry Louis Gates, Jr., Evelyn Brooks Higginbotham. (New York: Oxford University Press, 2004) R 920.9301451/AF83G African American writers. Valerie Smith, editor. Rev. ed. (New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 2000) R 810.9/AF83S Africana: the encyclopedia of the African and African American experience. (New York: Basic Civitas Books, 1999) R 301.451/AF83A Afro-American poetry and drama, 1760-1975: a guide to information sources. (Detroit: Gale, 1979) R 810.90/AF85. -

Sonny's Blues Study Guide

Sonny's Blues Study Guide © 2018 eNotes.com, Inc. or its Licensors. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. No part of this work covered by the copyright hereon may be reproduced or used in any form or by any means graphic, electronic, or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, taping, Web distribution or information storage retrieval systems without the written permission of the publisher. Summary The narrator, a teacher in Harlem, has escaped the ghetto, creating a stable and secure life for himself despite the destructive pressures that he sees destroying so many young blacks. He sees African American adolescents discovering the limits placed on them by a racist society at the very moment when they are discovering their abilities. He tells the story of his relationship with his younger brother, Sonny. That relationship has moved through phases of separation and return. After their parents’ deaths, he tried and failed to be a father to Sonny. For a while, he believed that Sonny had succumbed to the destructive influences of Harlem life. Finally, however, they achieved a reconciliation in which the narrator came to understand the value and the importance of Sonny’s need to be a jazz pianist. The story opens with a crisis in their relationship. The narrator reads in the newspaper that Sonny was taken into custody in a drug raid. He learns that Sonny is addicted to heroin and that he will be sent to a treatment facility to be “cured.” Unable to believe that his gentle and quiet brother could have so abused himself, the narrator cannot reopen communication with Sonny until a second crisis occurs, the death of his daughter from polio.