Watching Time: James Baldwin and Malcolm X

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Perched in Potential: Mobility, Liminality, and Blues Aesthetics

PERCHED IN POTENTIAL: MOBILITY, LIMINALITY, AND BLUES AESTHETICS IN THE WRITINGS OF JAMES BALDWIN by TAREVA LESELLE JOHNSON (Under the Direction of Valerie Babb) ABSTRACT James Baldwin’s mobility and appreciation for African American musical traditions play an integral part in the writer’s crossing of genre and subgenre, his unique style, and his preoccupation with repeated themes. The interplay of music and shifting space in Baldwin’s life and texts create liminal spaces for Baldwin and readers to enter. In these spaces, clearer understandings of the importance of exteriority and interiority, simultaneously, are achieved. This in-betweenness is a place of potential and power. Baldwin’s writing uses this power to chronicle his own growing consciousness and to create, with his collective works, and through them, Baldwininan literary theory that applies to his own works’ use of liminality, the blues and travel. One is able to overhear Baldwin speaking to himself via his texts at multiple points in his nearly forty-year career. INDEX WORDS: James Baldwin, Transatlantic, Liminal, Mobility, Blues, African American, Go Tell It on the Mountain, The Amen Corner, Sonny’s Blues, The Uses of the Blues, Paris, Turkey, Exile PERCHED IN POTENTIAL: MOBILITY, LIMINALITY, AND BLUES AESTHETICS IN THE WRITINGS OF JAMES BALDWIN by TAREVA LESELLE JOHNSON B.A., COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY, 2008 A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of The University of Georgia in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree MASTER OF ARTS ATHENS, GEORGIA 2012 © 2012 Tareva Leselle Johnson All Rights Reserved PERCHED IN POTENTIAL: MOBILITY, LIMINALITY, AND BLUES AESTHETICS IN THE WRITINGS OF JAMES BALDWIN by TAREVA LESELLE JOHNSON Major Professor: Valerie Babb Committee: Cody Marrs Barbara McCaskill Electronic Version Approved: Maureen Grasso Dean of the Graduate School The University of Georgia May 2012 iv DEDICATION I dedicate this project to my brother, Jerome, and everyone else who makes their way back time and time again. -

Equal in Paris

EQUAL IN PARIS An Autobiographical Story JAMES BALDWIN O N THE 19th of December, in 1949, head was chilling and abrupt, like the down- when I had been living in Paris beat of an axe-the hotel would certainly for a little over a year, I was ar- have gone bankrupt long before. It was said rested as a receiver of stolen goods and spent that this old man had not gone farther than eight days in prison. My arrest came about the door of his hotel for thirty years, which through an American tourist whom I had was not at all difficult to believe. He looked met twice in New York, who had been given as though the daylight would have killed my name and address and told to look me him. up. I was then living on the top floor of a I did not, of course, spend much of my ludicrously grim hotel on the rue du Bac, one time in this palace. The moment I began of those enormous dark, cold, and hideous living in French hotels I understood the establishments in which Paris abounds that necessity of French caf6s. This made it seem to breathe forth, in their airless, humid, rather difficult to look me up, for as soon stone-cold halls, the weak light, scurrying as I was out of bed I hopefully took notebook chambermaids, and creaking stairs, an odor and fountain pen off to the upstairs room of gentility long long dead. The place was of the Flore, where I consumed rather a lot run by an ancient Frenchman dressed in an of coffee and, as evening approached, rather elegant black suit which was green with age, a lot of alcohol, but did not get much writing who cannot properly be described as be- done. -

Redemptive Suffering and Spiritual Service in the Works of James Baldwin

Georgia State University ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University English Dissertations Department of English 2-2-2006 Reclaiming the Human Self: Redemptive Suffering and Spiritual Service in the Works of James Baldwin Francine LaRue Allen Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/english_diss Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Allen, Francine LaRue, "Reclaiming the Human Self: Redemptive Suffering and Spiritual Service in the Works of James Baldwin." Dissertation, Georgia State University, 2006. https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/english_diss/6 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Department of English at ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in English Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. RECLAIMING THE HUMAN SELF: REDEMPTIVE SUFFERING AND SPIRITUAL SERVICE IN THE WORKS OF JAMES BALDWIN by FRANCINE LARUE ALLEN Under the Direction of Professor Thomas McHaney ABSTRACT James Arthur Baldwin argues that the issue of humanity—what it means to be human and whether or not all people bear the same measure of human worth—supersedes all issues, including socially popular ones such as race and religion. As a former child preacher, Baldwin claims, like others shaped by both the African-American faith tradition and Judeo- Christianity, that human equality stands as a divinely mandated and philosophically sound concept. As a literary artist and social commentator, Baldwin argues that truth in any narrative text, whether fictional or non-fictional, lies in its embrace or rejection of human equality. Truth-telling narrative texts uphold human equality; false-witnessing texts do not. -

Homosexuality in James Baldwin's Novels

RESEARCH PAPER English Volume : 5 | Issue : 9 | September 2015 | ISSN - 2249-555X Homosexuality in James Baldwin’s Novels KEYWORDS Homosexual, James Baldwin, African American gay writers, Racism, Religious. Ibrahim Mohammed Ali Alfagih Dr. A Y.Badgujar Research Guide Arts, Commerce &Science College PhD. Student,English Department, NMU (Varangaon) ABSTRACT James Baldwin was African American novelist and social critic. He was born illegitimate and black boy. But he became a well- known writer in bisexual and queer in African American literature writing with his novels. Baldwin’s acclaimed novels are Go Tell It on the Mountain, Giovanni’s Room, Another Country, Tell Me How Long the Train Been Gone, If Beale Street Could Talk, and Just Above My Head. This paper tries to show how homosexual is used in James Baldwin’s novels. James Baldwin carefully studied and dis- guised the homosexual theme in the first novel through John who was searching for his existence or identity, While, in Giovanni’s Room, homosexual was fully undisguised. The success of Giovanni’s Room as a gay and white novel made Baldwin to choose homosexual as main theme in his later novels. So, Baldwin opened the door in front of the next generation of gay writers to study and discus gay theme in their works. James Baldwin had difficulties in his childhood life. He did It portrays the efforts and life of John Grimes. It comes to not know his biological father. He had complex and tough terms with John African American cultural inheritance and relationship with his step-father. His father showed a strict his homosexuality. -

Negotiating Black Nationalism and Queerness in James Baldwin's Late Novels

University of Mississippi eGrove Electronic Theses and Dissertations Graduate School 2013 The Song We Sing: Negotiating Black Nationalism And Queerness In James Baldwin's Late Novels Elliot N. Long University of Mississippi Follow this and additional works at: https://egrove.olemiss.edu/etd Part of the American Literature Commons Recommended Citation Long, Elliot N., "The Song We Sing: Negotiating Black Nationalism And Queerness In James Baldwin's Late Novels" (2013). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. 547. https://egrove.olemiss.edu/etd/547 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at eGrove. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of eGrove. For more information, please contact [email protected]. “THE SONG WE SING”: NEGOTIATING BLACK NATIONALISM AND QUEERNESS IN JAMES BALDWIN’S LATE NOVELS A Thesis presented in partial fulfillment of requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in the Department of English The University of Mississippi by ELLIOT N. LONG June 2013 Copyright Elliot N. Long 2013 ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ABSTRACT Despite his exclusion from the Black Arts Movement, James Baldwin includes in his later novels many elements of Black Nationalism, including a focus on black communities, black music, Pan-Africanism, and elements of separatism. In his inclusion of queer sexuality, Baldwin pushes against the typical bounds of Black Arts writings, expanding the limits of the genre. Contrary to the philosophy of Black Nationalism, which depends upon solid definitions of blackness, heterosexuality, and masculinity, is Baldwin’s tearing down of identity categories through queering sexuality, gender, and race. -

James Baldwin, the Religious Right, and the Moral Minority

ESSAY “To Crush the Serpent”: James Baldwin, the Religious Right, and the Moral Minority Joseph Vogel Merrimack College Abstract In the 1980s, James Baldwin recognized that a major transformation had occurred in the socio- political functions of religion. His critique adapted accordingly, focus- ing on the ways in which religion—particularly white evangelical Christianity— had morphed into a movement deeply enmeshed with mass media, conservative politics, and late capitalism. Religion in the Reagan era was leveraged, sold, and consumed in ways never before seen, from charismatic televangelists, to Christian- themed amusement parks, to mega- churches. The new movement was often char- acterized as the “religious right” or the “Moral Majority” and was central to both Reagan’s political coalition as well as the broader culture wars. For Baldwin, this development had wide- ranging ramifications for society and the individual. This article draws on Baldwin’s final major essay, “To Crush the Serpent” (1987), to examine the author’s evolving thoughts on religion, salvation, and transgression in the context of the Reagan era. Keywords: James Baldwin, religion, Moral Majority, religious right, Ronald Reagan, “To Crush the Serpent,” 1980s At some point in the 1980s, James Baldwin must have been flipping through chan- nels on TV and stumbled upon an appearance of Jerry Falwell on Nightline, or perhaps Pat Robertson’s talk show, The 700 Club, or maybe Jim and Tammy Faye Bakker’s Praise the Lord (PTL) network. These figures were so ubiquitous during the Reagan era it would have been difficult not to. While we may never know the full range of thoughts looming behind those large, inquisitive eyes, Baldwin, fortunately, did leave behind a written record on the subject that offers important insights into the author’s evolving thoughts on religion, salvation, and transgres- sion from the final decade of his life. -

Reading and Theorizing James Baldwin: a Bibliographic Essay

BIBLIOGRAPHIC ESSAY Reading and Theorizing James Baldwin: A Bibliographic Essay Conseula Francis College of Charleston, South Carolina Abstract Readers and critics alike, for the past sixty years, generally agree that Baldwin is a major African-American writer. What they do not agree on is why. Because of his artistic and intellectual complexity, Baldwin’s work resists easy categori- zation and Baldwin scholarship, consequently, spans the critical horizon. This essay provides an overview of the three major periods of Baldwin scholarship. 1963–73 is a period that begins with the publication of The Fire Next Time and sees Baldwin grace the cover of Time magazine. This period ends with Time declaring Baldwin too passé to publish an interview with him and with critics questioning his relevance. The second period, 1974–87, finds critics attempting to rehabilitate Baldwin’s reputation and work, especially as scholars begin to codify the African-American literary canon in anthologies and American universities. Finally, scholarship in the period after Baldwin’s death takes the opportunity to challenge common assumptions and silences surrounding Baldwin’s work. Armed with the methodologies of cultural studies and the critical insights of queer theory, critics set the stage for the current Baldwin renaissance. Keywords: James Baldwin, critical reception, literary history, literary criticism, African-American literature Considering the critical reception of James Baldwin is difficult for a number of reasons. First, Baldwin was a widely reviewed, widely studied, prolific author. He published twenty-two full-length works in his lifetime, in addition to many essays, reviews, introductions, and interviews. In addition, his career was quite long. -

Sonny's Blues Study Guide

Sonny's Blues Study Guide © 2018 eNotes.com, Inc. or its Licensors. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. No part of this work covered by the copyright hereon may be reproduced or used in any form or by any means graphic, electronic, or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, taping, Web distribution or information storage retrieval systems without the written permission of the publisher. Summary The narrator, a teacher in Harlem, has escaped the ghetto, creating a stable and secure life for himself despite the destructive pressures that he sees destroying so many young blacks. He sees African American adolescents discovering the limits placed on them by a racist society at the very moment when they are discovering their abilities. He tells the story of his relationship with his younger brother, Sonny. That relationship has moved through phases of separation and return. After their parents’ deaths, he tried and failed to be a father to Sonny. For a while, he believed that Sonny had succumbed to the destructive influences of Harlem life. Finally, however, they achieved a reconciliation in which the narrator came to understand the value and the importance of Sonny’s need to be a jazz pianist. The story opens with a crisis in their relationship. The narrator reads in the newspaper that Sonny was taken into custody in a drug raid. He learns that Sonny is addicted to heroin and that he will be sent to a treatment facility to be “cured.” Unable to believe that his gentle and quiet brother could have so abused himself, the narrator cannot reopen communication with Sonny until a second crisis occurs, the death of his daughter from polio. -

ITL Frontmatter

thein A BLACK GAY ANTHOLOGY thein A BLACK GAY ANTHOLOGY edited by Joseph Beam New Introduction by James Earl Hardy WASHINGTON, DC www.redbonepress.com In the Life: A Black Gay Anthology Copyright © 1986 by Joseph Beam; © 2008 by Estate of Joseph Beam New Introduction, “And We Continue to Go the Way Our Blood Beats...” copyright © 2008 by James Earl Hardy Individual selections copyright © by their respective author(s) Published by: RedBone Press P.O. Box 15571 Washington, DC 20003 All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means without permission in writing from the publisher, except in the case of reviews. 08 09 10 11 12 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 Second edition Cover design by Eunice Corbin Logo design by Mignon Goode Joseph Beam cover photo copyright © 1985 by Sharon Farmer Permissions acknowledgments appear on pp. 219. Artwork on p. 1 by Deryl Mackie; photograph on p. 23 by Joseph Beam; artwork on p. 45 by Don Reid; artwork on p. 69 by Vega; artwork on p. 115 by Tawa; photograph on p. 173 by Joseph Beam. Printed in the United States of America ISBN-13: 978-0-9786251-2-2 ISBN-10: 0-9786251-2-9 www.redbonepress.com for my parents, Dorothy and Sun F. Beam for loving for Kenyatta Ombaka Baki for believing for Addie and Charles for our future Contents And We Continue to Go the Way Our Blood Beats..., by James Earl Hardy / ix Acknowledgments / xv Introduction / xix Coming of Age, Brad Johnson / xxv Stepping Out The Boy with Beer, Melvin Dixon / 2 With My Head Held Up High, Gilberto Gerald / 14 Cut Off from Among Their People On Not Being White, Reginald Shepherd / 24 Beautiful Blackman, Blackberri / 35 Don’t Turn Your Back on Me, Stephan Lee Dais / 37 Cut Off from Among Their People, Craig G. -

Staging Civil Rights: African American Literature, Performance, and Innovation

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations 2014 Staging Civil Rights: African American Literature, Performance, and innovation Julius B. Fleming Jr University of Pennsylvania, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations Part of the African American Studies Commons, English Language and Literature Commons, and the Theatre and Performance Studies Commons Recommended Citation Fleming Jr, Julius B., "Staging Civil Rights: African American Literature, Performance, and innovation" (2014). Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations. 1276. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/1276 This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/1276 For more information, please contact [email protected]. Staging Civil Rights: African American Literature, Performance, and innovation Abstract This dissertation examines the relationship between African American literature and performance during the modern Civil Rights Movement. It traces the ways in which the movement was acted out on the theatrical stage as creatively as it was at those sites of embodied activism that have survived in intellectual and popular memories: lunch counters and buses, schools and courtrooms, streets and prisons. Whereas television and photography have served as primary ways of knowing the movement, this project turns to African American literature, and the live performances it inspired, to provide a more complex framework for analyzing the -

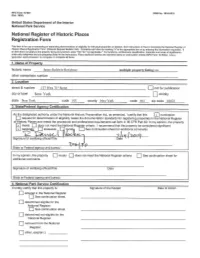

James Baldwin Residence Multiple Property Listing: No Other Names/Site Number 2

NPS Form 10-900 OMB No. 1024-0018 (Oct. 1990) United States Department of the Interior National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Registration Form This form is for use in nominating or requesting determinations of eligibility for individual properties or districts. See instructions in How to Complete the National Register of Historic Places Registration Form (National Register Bulletin 16A). Complete each item by marking "x" in the appropriate box or by entering the information requested. If an item does not apply to the property being documented, enter "N/A" for "not applicable." For functions, architectural classification, materials and areas of significance, enter only categories and subcategories listed in the instructions. Place additional entries and narrative items on continuation sheets (NPS Form 10-900a). Use a typewriter, word processor, or computer, to complete all items. 1. Name of Property historic name James Baldwin Residence multiple property listing: no other names/site number 2. Location street & number 137 West 71st Street not for publication city or town New York vicinity state New York code NY county New York code 061 zip code 10023 3. State/Federal Agency Certification As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act, as amended, I certify that this x nomination request for determination of eligibility meets the documentation standards for registering properties in the National Register of Historic Places and meets the procedural and professional requirements set forth in 36 CFR Part 60. In my opinion, the property x meets does not meet the National Register criteria. I recommend that this property be considered significant x nationally statewide locally. -

Bibliography James Baldwin

PD Dr. Stefan L. Brandt Summer Term 2009 James Baldwin and the Literary Constitution of Blackness Selected Bibliography Primary works (selection) Nonfiction “Anti-Semitism and Black Power.” Freedomways 7 (Winter 1967): 75-77. “As Much Truth as One Can Bear.” New York Times Book Review (14 Jan. 1962): 1, 38. Conversations with James Baldwin . Eds. Fred L. Standley and Louis H. Pratt. Jackson: Univ. Press of Mississippi, 1989. A Dialogue . James Baldwin and Nikki Giovanni. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott, 1973. The Fire Next Time . New York: Dial Press, 1963. “Go the Way Your Blood Beats.” [1984]. Interview with Richard Goldstein. In: Troupe, Quentin, ed., James Baldwin: The Legacy , 1989. 173-185. “History as Nightmare.” New Leader 30 (25 Oct. 1947): 11, 15. “Liberalism and the Negro: A Roundtable Discussion.” Commentary 37 (March 1964): 25-42. “The Negro in American Culture.” Cross Currents XI (1961): 205. “The Nigger We Invent.” Integrated Education 7 (March/Apr. 1969): 15-23. Nobody Knows My Name: More Notes of a Native Son . New York: The Dial Press, 1961. Here especially: “The Discovery of What It Means to Be an American” (3-12). “Alas, Poor Richard” (181-215). “The Black Boy Looks at the White Boy” (216-241). “The Male Prison” (155-162). Notes of a Native Son. Boston: Beacon Press, 1955. Here especially: “Everybody’s Protest Novel” (13-23). “Many Thousands Gone” (24-45). “Notes of a Native Son” (85-114). “Equal in Paris” (138-158). Nothing Personal . With photographs by Richard Avedon. New York: Penguin Books, 1964. The Price of the Ticket. Collected Nonfiction, 1948-1985 .