Brian Friel's Invocation of Edmund Burke in Philadelphia, Here I Come!

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Making History

Retorica e Storia in Making History di Brian Friel Manfredi Bernardini to tell the best possible narrative. Isn’t that what history is, a kind of story-telling? […] Imposing a pattern on events that were mostly casual and haphazard and shaping them into a narrative that is logical and interesting. […] I’m not sure that ‘truth’ is a primary ingredient – is that a shocking thing to say? Maybe when the time comes, imagination will be as important as information. But one thing I will promise you: nothing will be put down on paper for years and years. History has to be made - before it’s remade1. Brian Friel, Making History Non sappiamo che cosa sarebbe una cultura nella quale non si sappia più che cosa significhi raccontare2. Paul Ricoeur, Tempo e Racconto Fin dalle epoche più remote le storie sono state un veicolo di trasmissione di cultura e sapere. Prima della diffusione della scrittura le antiche civiltà trasmettevano oralmente immensi patrimoni di conoscenza, affidando alle immagini dei miti e degli archetipi il compito fondamentale di perpetuare l’esperienza, la storia e l’identità stessa di un popolo. 1 Cfr. Friel, Brian, Making History, Londra, Faber and Faber, 1989: 257-258. 2 Cfr. Ricoeur, Paul, Temps et récit, Parigi, Le Seuil, 1983, trad. it. Tempo e Racconto, Milano, Jaca Book, 1994: 54.. Between, vol. III, n. 5 (Maggio/ May 2013) Manfredi Bernardini, Retorica e Storia in Making History di Brian Friel La tradizione del racconto orale, delle folk tales narrate intorno al focolare, della memoria culturale, storica (e mitica) condivisa e tramandata di generazione in generazione, costituisce un’attività in cui poeti e cantori, bardi e moderni scrittori si sono cimentati con esiti abbastanza duraturi. -

Language and Communication Strategies in Brian Friel’S Tra�Slatio�S and Da�Ci�G at Lugh�Asa”

FACULTADE DE FILOLOXÍA GRAO EN INGLÉS: ESTUDOS LINGÜÍSTICOS E LITERARIOS “LANGUAGE AND COMMUNICATION STRATEGIES IN BRIAN FRIEL’S TRANSLATIONS AND DANCING AT LUGHNASA” OLIVIA DANS CASTRO ANO ACADÉMICO: 2012/2013 Language and Communication Strategies… Table of contents 1. Foreword ................................................................................................................................ 3 2. Introduction ............................................................................................................................ 4 3. Author and historical background.......................................................................................... 7 4. Translations............................................................................................................................ 9 4.1 Friel and Steiner ............................................................................................................. 12 4.2 Translating the Irish ....................................................................................................... 17 4.2.1 Language and politics.............................................................................................. 24 4.2.2 Names...................................................................................................................... 26 4.2.3 Place and memory ................................................................................................... 28 4.2.4 The three Irelands................................................................................................... -

Brian Friel's Appropriation of the O'donnell Clan

University of Louisville ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository Electronic Theses and Dissertations 5-2008 Celtic subtleties : Brian Friel's appropriation of the O'Donnell clan. Leslie Anne Singel 1984- University of Louisville Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.library.louisville.edu/etd Recommended Citation Singel, Leslie Anne 1984-, "Celtic subtleties : Brian Friel's appropriation of the O'Donnell clan." (2008). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. Paper 1331. https://doi.org/10.18297/etd/1331 This Master's Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository. This title appears here courtesy of the author, who has retained all other copyrights. For more information, please contact [email protected]. "CELTIC SUBTLETIES": BRIAN FRIEL'S APPROPRIATION OF THE O'DONNELL CLAN By Leslie Anne Singel B.A., University of Dayton, 2006 A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School at the University of Louisville in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts Department of English University of Louisville Louisville, Kentucky May 2008 “CELTIC SUBLETIES”: BRIAN FRIEL’S APPROPRIATION OF THE O’DONNELL CLAN By Leslie Anne Singel B.A., University of Dayton, 2006 A Thesis Approved on April 9, 2008 by the following Thesis Committee: Thesis Director ii DEDICATION This thesis is dedicated to the McGarry family and to Roger Casement 111 ABSTRACT "CELTIC SUBTLETIES": BRIAN FRIEL'S APPROPRIATION OF THE O'DONNELL CLAN Leslie Anne Singel April 11, 2008 This thesis is a literary examination of three plays from Irish playwright Brian Friel, Translations, Philadelphia, Here I Come! and Aristocrats, all of which feature a family ofthe O'Donnell name and all set in the fictional Donegal village of Ballybeg. -

Brian Friel: Titles Plays: Translations / Making History

Brian Friel: Titles This is a compilation of some of the titles submitted by centres in Summer 2009. It is not a definitive or prescriptive list of titles but it will give an idea as to different approaches to the task. Some student devised titles have not been listed as, while many have been successful due to the interest of the student, they may not be as successful if given to a class. Titles with a similar focus, but with e.g. a different location or form of writing, have been subsumed into each other to keep a concise list of approaches. Plays: Translations / Making History Flashback of Hugh O’Donnell remembering how he marched to Sligo to take part in the 1798 United Irishmen Rebellion, along with his friend Jimmy Jack Cassie. Hugh remembers that he decided to return to Ballybeg instead of going through with the rebellion. He feels a sense of shame that he did not take part in the uprising. Hugh is visited by a vision of Hugh O’Neill (from Making History). Create the scene. Write a scene in which Yolland from Translations and Mabel from Making History engage in dialogue, discussing their lives. Write a scene in which Lieutenant Yolland from Translations and Hugh O’Neill from Making History engage in dialogue and discuss their lives. Write a scene in which Lieutenant Yolland from Translations and Mabel O’Neill from Making History engage in dialogue and discuss their lives. Through having the characters of Hugh O’Donnell and Hugh O’Neill “meet”, develop a dialogue, exploring the connections and comparisons between the themes of identity, language , history which are evident in both plays. -

6 X 10.5 Long Title.P65

Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-66686-2 - The Cambridge Companion to Brian Friel Edited by Anthony Roche Frontmatter More information The Cambridge Companion to Brian Friel Brian Friel is widely recognized as Ireland’s greatest living playwright, win- ning an international reputation through such acclaimed works as Transla- tions (1980) and Dancing at Lughnasa (1990). This collection of specially commissioned essays includes contributions from leading commentators on Friel’s work (including two fellow playwrights) and explores the entire range of his career from his 1964 breakthrough with Philadelphia, Here I Come! to his most recent success in Dublin and London with The Home Place (2005). The essays approach Friel’s plays both as literary texts and as performed drama, and provide the perfect introduction for students of both English and Theatre Studies, as well as theatregoers. The collection considers Friel’s lesser-known works alongside his more celebrated plays and provides a comprehensive crit- ical survey of his career. This is the most up-to-date study of Friel’s work to be published, and includes a chronology and further reading suggestions. anthony roche is Senior Lecturer in English and Drama at University College Dublin. He is the author of Contemporary Irish Drama: From Beckett to McGuinness (1994). © Cambridge University Press www.cambridge.org Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-66686-2 - The Cambridge Companion to Brian Friel Edited by Anthony Roche Frontmatter More information THE CAMBRIDGE COMPANION TO BRIAN FRIEL -

Performative Landscapes As Conceptual Ecological Environments

Provided by the author(s) and NUI Galway in accordance with publisher policies. Please cite the published version when available. Title Re-place: performative landscapes as conceptual ecological environments Author(s) FitzGerald, Lisa Publication Date 2016-09-27 Item record http://hdl.handle.net/10379/6049 Downloaded 2021-09-26T08:24:41Z Some rights reserved. For more information, please see the item record link above. Re-Place: Performative Landscapes as Conceptual Ecological Environments. Author Lisa FitzGerald, M. Res. A dissertation submitted to English Department, School of Humanities College of Arts, Social Sciences, and Celtic Studies National University of Ireland, Galway In Partial Fulfilment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy August 2016 Supervisor Professor Patrick Lonergan Table of Contents 1) Abstract iv 2) Acknowledgements v 3) List of Illustrations vi 4) Chapter One 1.1 Thesis Introduction 1 Conceptual Ecological Environments 1 1.2 Methodology 6 Culture 9 Nature 10 1.3 Literature Review 14 Ecocriticism 16 Ecocriticism and Space and Place in Irish Studies 37 1.4 Conclusion 60 5) Chapter Two Conceptualizing the West 2.1 Introduction 63 2.2 Riders to the Sea 65 2.3 The Well of Saints 73 2.4 Druid/Synge 86 2.5 Conclusion 96 i 6) Chapter Three Beckett’s Fragmented Environments 3.1 Introduction 99 3.2 All That Fall 100 3.3 Urban Sustainability and Not I 114 3.4 Pan Pan’s Staging of Beckett’s Radio Plays 127 3.5 Conclusion 135 7) Chapter Four Conceptualizing the North 4.1 Introduction 137 4.2 Translations 142 Mapping 145 Hedge Schools 151 4.3 Exile and the North in Making History 156 4.4 Ouroboros/Making History 161 4.5 Conclusion 167 ii 8) Chapter Five Digital Environments 5.1 Introduction 172 5.2 Druid Archive as Conceptual Environment 180 5.3 The Ongoing Performativity of Digital Documentation 184 5.4 Material Networks: Contesting Ephemerality 192 5.5 Conclusion 198 9) Overall Conclusions 6.1 Introduction 200 6.2 Reflecting on Transformations: Careers. -

Dancing at Lughnasa, Dublin and New York

Provided by the author(s) and NUI Galway in accordance with publisher policies. Please cite the published version when available. Title Dancing on a one-way street: Irish reactions to Dancing at Lughnasa in New York Author(s) Lonergan, Patrick Publication Date 2009 Lonergan, Patrick. (2009). Dancing on a One-Way Street: Irish Publication Reactions to Dancing at Lughnasa in New York In John P. Information Harrington (Ed.), Irish theater in America : essays on Irish theatrical diaspora New York: Syracuse University Press. Publisher Syracuse University Press Link to publisher's http://www.syracuseuniversitypress.syr.edu/ version Item record http://hdl.handle.net/10379/6789 Downloaded 2021-09-27T12:30:41Z Some rights reserved. For more information, please see the item record link above. 1 Dancing on a One-Way Street: Irish Reactions to Dancing at Lughnasa in New York Brian Friel’s Dancing at Lughnasa is an important example of the inter-relationship of American and Irish theatre, particularly since 1990. Its script draws heavily on American culture, bringing us songs by Cole Porter and an approach to the narration of remembered events that is highly reminiscent of the work of Tennessee Williams. And its production was one of the first of many Irish successes on the New York stage from the 1990s onwards, being followed by productions of plays by Martin McDonagh, Conor McPherson and indeed by Brian Friel himself, whose Faith Healer was a critical and commercial success on Broadway in 2006. Dancing at Lughnasa premiered on 24 April 1990 at the Abbey Theatre, where it was directed by Patrick Mason. -

Instead of an Obituary. Brian Friel's Silent Voices. Memory And

Studi irlandesi. A Journal of Irish Studies, n. 6 (2016), pp. 11-16 DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.13128/SIJIS-2239-3978-18452 Instead of an Obituary. Brian Friel’s Silent Voices. Memory and Celebration Giovanna Tallone Independent scholar (<[email protected]>) On the occasion of Brian Friel’s eightieth birthday in 2009, Seamus Heaney published a slender volume called Spelling It Out, whose aim was to honour and celebrate the playwright and to mark a long-standing friendship. Taking the letters of Friel’s name and surname in a game with words and language, Heaney created a sort of microcosm of Friel’s world. Starting with B, for Ballybeg, “the invented domain where so many of Brian’s plays are set, the hub of his imagined world” (Heaney 2009, [3]), the poet moves on to I “for in- tegrity”, but also for “Ireland” and for “intimacy”, thus mixing the public and the personal, “the inner self, the mysterious source and living of being” ([5]). At the same time this is a reminder of the stage directions in Philadelphia, Here I Come! (1964), where Gar O’Donnell is split between Public Gar and Private Gar, the latter being “the unseen man, the man within, the alter ego, the se- cret thoughts, the id” (Friel 1984, 27). Words like “no”, “fiction”, “experiment”, “love” and “language” are likewise entered in what Heaney defines “not so much an abecedary as a befrielery” ([1]), in an interplay of public and private levels. The death of Brian Friel on October nd2 2015 followed Heaney’s death about two years earlier, which meant the loss of two of the deepest, most eminent and most provocative voices in Irish literature and culture, whose echoes resound in the second half of the twentieth century and into the twen- ty-first. -

Brian Friel's Translations, a Play on Power, Space, and History

Khazar Journal of Humanities and Social Sciences Volume 23 № 1 2020, 5-21 © Khazar University Press 2020 DOI: 10.5782/2223-2621.2020.23.1.5 Brian Friel’s Translations, a Play on Power, Space, and History Maryam Beyad1, Mohammad Bagher Shabanpour2, * 1, 2University of Tehran, Tehran, Iran *Corresponding author: [email protected] Abstract Geography has received great attention since the 19th century. Kant established it as a discipline which resulted in the development of geographical equipment. Consequently, surveying projects were launched in England. This paper argues that Friel’s Translations depicts the extinction of the Irish culture, done by the Army’s implementation of Ireland Ordnance Survey in 1830, in which Irish/Gaelic toponyms, carrying a great volume of a people’s history, were anglicised. The English Empire strengthened its domination over Ireland through creating new maps of the Northern territories. The paper does a Foucauldian reading of geography, as a contemporary knowledge, which aided the reconstitution of the British power to hamper the contemporary revolutions or invasions. It maintains that Translations is a play on space and history, in which the role of space outweighs that of time, so does the production of a new space and the extinction of old spaces through Ordnance Survey. Keywords: Brian Friel, Translations, Space, Geography, History, Power and Knowledge, Toponym Introduction Brian Friel (1929-2015) was an Irish dramatist and short story writer, known as one of the greatest contemporary dramatists writing in English. He was born in Omagh, in County Tyrone, one of the six counties of Northern Ireland. -

The Translations of Brian Friel, Translations and Dancing at Lughnasa

Between Words and Meaning The translations of Brian Friel, Translations and Dancing at Lughnasa A Thesis submitted in fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the University of Canterbury by Cassandra M. F. Fusco University of Canterbury 1998 "Gan cuimhne, duramar aris agus aris eile, nil aon phrionsabal i ndochas" (Ricoeur) I gcuimhne ar m' athair agus ar mo mhathair agus Mira. Is iomai duine a bhfuil me faoi chomaoin aige as an gcuidiu a tugadh dom, ag cur an trachtais seo Ie cMile. Sa gcead ait, ta me faoi chomaoin ag mo thuismitheoiri, a dtiolacaim an staidear seo doibh, ag teaghlach mo bhreithe, idir mharbh agus bheo, go hairithe ag Edward agus Jacqueline, ag m'fhear ceile agus ag ar gc1ann fein, agus John Goodliffe, agus sgolair Gordon Spence. Uathasan, agus 0 mo chairde sa da leathsfear, d'fhoghlaim me tabhacht na cumarsaide, bainte amach go minic Ie stro, tri litreacha lena mbearnai dosheacanta. 'Is iontach an marc a d'fh:ig an comhfhreagras ar mo shaol agus ar mo chuid staideir. Ta me faoi chomaoin, freisin, ag obair Bhrain Ui Fhrighil - focas mo chuid staideir -, ag an fhear fein agus ag a chomhleacaithe a thug freagrai chomh morchroioch sin dom ar na ceisteanna 0 na fritiortha. Is beag duine a ainmnitear anseo ach, mar is leir on trachtas fein, on leabharliosta agus 0 na notai buiochais, chuidigh a Ian daoine liom. Beannaim d' achan duine agaibh, gabhaim buiochas libh agus iarraim pardun oraibh as aon easpa, biodh si ina easpa phearsanta no acaduil, mar nil baint aici leis an muinin, an trua na an ionrachas a thaispeanann sibh, ach cuireann :ir n-easpai i gcuimhne duinn nach foirfe riamh an duine, ach oiread leis an tsamhlaiocht, agus nach mor do coinneailleis ar a aistear. -

Translations

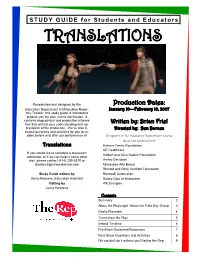

STUDY GUIDE for Students and Educators TRANSLATIONS Researched and designed by the Production Dates: Education Department at Milwaukee Reper- January 10—February 10, 2007 tory Theater, this study guide is intended to prepare you for your visit to the theater. It contains biographical and production informa- tion that will aid your understanding and ap- Written by: Brian Friel preciation of the production. We’ve also in- Directed by: Ben Barnes cluded questions and activities for you to ex- plore before and after our performance of Programs in the Education Department receive generous funding from: Translations Einhorn Family Foundation GE Healthcare If you would like to schedule a classroom Halbert and Alice Kadish Foundation workshop, or if we can help in some other way, please contact (414) 290-5370 or Harley Davidson [email protected] Milwaukee Arts Board Richard and Ethel Herzfeld Foundation Study Guide written by Rockwell Automation Dena Roncone, Education Assistant Rotary Club of Milwaukee Editing by WE Energies Jenny Kostreva Contents Summary 2 About the Playwright /About the Field Day Group 3 Gaelic Proverbs 4 Terms from the Play 5 Ireland Timeline 6 Pre-Show Questions/Resources 7 Post-Show Questions and Activities 8 We couldn’t do it without you/Visiting the Rep 9 1 Summary Translations takes place in a hedge-school in the Book. Yolland keeps getting distracted from his work townland of Baile Beag/Ballybeg, an Irish-speaking and discusses the beauty of the country, the language community in County Donegal. and the people. Yolland wants to learn Gaelic and con- templates living in Ireland. -

Brian Friel and Contemporary Irish Drama

Colby Quarterly Volume 27 Issue 4 December Article 3 December 1991 Brian Friel and Contemporary Irish Drama Richard Pine Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.colby.edu/cq Recommended Citation Colby Quarterly, Volume 27, no.4, December 1991, p.190-201 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Digital Commons @ Colby. It has been accepted for inclusion in Colby Quarterly by an authorized editor of Digital Commons @ Colby. Pine: Brian Friel and Contemporary Irish Drama Brian Friel and Contemporary Irish Drama by RICHARD PINE ven though Brian Friel might appear to be far removed from the "classic" EIrish writers illuminated by the late Richard Ellman, there is a distinct context in which his work on Wilde, Yeats, and Beckett leads naturally into the field ofcontemporary Ireland and its drama.) In his finest book, Four Dubliners, EHmann says thatthese writers dislodge and subverteverything except truth; that "displaced, witty, complex, savage, they conlpanion each other," that "they share with their island a tense struggle for autonomy, a disdain for occupation by outside authorities, and a good deal of inner division."2 Ishall make three clainls for Brian Friel: first, that on September 28 1964 with the premiere of Philadelphia, Here I Come! he became the father ofcontempo rary Irish drama; second, that he occupies a central position in modem interna tional drama, with specific regard to post-colonialism; and third, that as a thinker he has a crucial relationship to the development of modem criticism. Let me begin to substantiate these claims by referring to the way Friel is perceived as the author of Philadelphia, Here I Come! wherein preoccupa tions-family relationships, social change, the land, adolescence, emigration, the telling of secrets-continue to resonate within Irish drama and the Irish historical and political experience.