TCRP Report 49

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Metro Bus and Metro Rail System

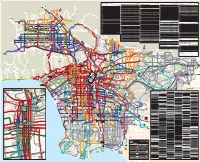

Approximate frequency in minutes Approximate frequency in minutes Approximate frequency in minutes Approximate frequency in minutes Metro Bus Lines East/West Local Service in other areas Weekdays Saturdays Sundays North/South Local Service in other areas Weekdays Saturdays Sundays Limited Stop Service Weekdays Saturdays Sundays Special Service Weekdays Saturdays Sundays Approximate frequency in minutes Line Route Name Peaks Day Eve Day Eve Day Eve Line Route Name Peaks Day Eve Day Eve Day Eve Line Route Name Peaks Day Eve Day Eve Day Eve Line Route Name Peaks Day Eve Day Eve Day Eve Weekdays Saturdays Sundays 102 Walnut Park-Florence-East Jefferson Bl- 200 Alvarado St 5-8 11 12-30 10 12-30 12 12-30 302 Sunset Bl Limited 6-20—————— 603 Rampart Bl-Hoover St-Allesandro St- Local Service To/From Downtown LA 29-4038-4531-4545454545 10-12123020-303020-3030 Exposition Bl-Coliseum St 201 Silverlake Bl-Atwater-Glendale 40 40 40 60 60a 60 60a 305 Crosstown Bus:UCLA/Westwood- Colorado St Line Route Name Peaks Day Eve Day Eve Day Eve 3045-60————— NEWHALL 105 202 Imperial/Wilmington Station Limited 605 SANTA CLARITA 2 Sunset Bl 3-8 9-10 15-30 12-14 15-30 15-25 20-30 Vernon Av-La Cienega Bl 15-18 18-20 20-60 15 20-60 20 40-60 Willowbrook-Compton-Wilmington 30-60 — 60* — 60* — —60* Grande Vista Av-Boyle Heights- 5 10 15-20 30a 30 30a 30 30a PRINCESSA 4 Santa Monica Bl 7-14 8-14 15-18 12-18 12-15 15-30 15 108 Marina del Rey-Slauson Av-Pico Rivera 4-8 15 18-60 14-17 18-60 15-20 25-60 204 Vermont Av 6-10 10-15 20-30 15-20 15-30 12-15 15-30 312 La Brea -

MCT CONSIDERS CHANGES to SENIOR FREE RIDE PROGRAM MCT Will Host Public Meetings June 7-8, 2011

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE For more information, contact: Jerry Kane Madison County Transit (618) 797-4600 MCT CONSIDERS CHANGES TO SENIOR FREE RIDE PROGRAM MCT will Host Public Meetings June 7-8, 2011 GRANITE CITY, ILL., MAY 16, 2011… Madison County Transit (MCT) is hosting three meetings to solicit public comment on proposed changes to the Senior Free Ride Program for its fixed-route service. If approved, MCT will conform to Illinois Public Act 96-1527 and only provide free rides on its fixed route for seniors who qualify based on age and income level. The change would take effect in August 2011. In January 2008, the Illinois General Assembly approved former Governor Blagojevich’s amended Mass Transit Bill, which provided free rides on transit for Illinois residents, age 65 and up. In February of this year, Governor Quinn signed legislation to reform the Senior Free Rides program, limiting the program to only those seniors who earn less than $27,610 for a one-person household, $36,635 for a two-person household and $45,657 for a three-person household. MCT Public meeting dates, times and locations to discuss the changes are listed below: Tuesday, June 7 (2:00 – 3:00 p.m.) MCT Granite City Station Wednesday, June 8, (2:00 – 3:00 p.m.) MCT Alton Station Wednesday, June 8, (6:00 – 7:00 p.m.) MCT Edwardsville Station Comments at the public meetings will be summarized and presented to the MCT Board of Trustees for consideration. Individuals who cannot attend the meetings but would like to comment, should e-mail [email protected] or send a letter to: Madison County Transit, Attn: Senior Free Ride Comments, One Transit Way, PO Box 7500, Granite City, IL 62040. -

Transit Service Plan

Attachment A 1 Core Network Key spines in the network Highest investment in customer and operations infrastructure 53% of today’s bus riders use one of these top 25 corridors 2 81% of Metro’s bus riders use a Tier 1 or 2 Convenience corridor Network Completes the spontaneous-use network Focuses on network continuity High investment in customer and operations infrastructure 28% of today’s bus riders use one of the 19 Tier 2 corridors 3 Connectivity Network Completes the frequent network Moderate investment in customer and operations infrastructure 4 Community Network Focuses on community travel in areas with lower demand; also includes Expresses Minimal investment in customer and operations infrastructure 5 Full Network The full network complements Muni lines, Metro Rail, & Metrolink services 6 Attachment A NextGen Transit First Service Change Proposals by Line Existing Weekday Frequency Proposed Weekday Frequency Existing Saturday Frequency Proposed Saturday Frequency Existing Sunday Frequency Proposed Sunday Frequency Service Change ProposalLine AM PM Late AM PM Late AM PM Late AM PM Late AM PM Late AM PM Late Peak Midday Peak Evening Night Owl Peak Midday Peak Evening Night Owl Peak Midday Peak Evening Night Owl Peak Midday Peak Evening Night Owl Peak Midday Peak Evening Night Owl Peak Midday Peak Evening Night Owl R2New Line 2: Merge Lines 2 and 302 on Sunset Bl with Line 200 (Alvarado/Hoover): 15 15 15 20 30 60 7.5 12 7.5 15 30 60 12 15 15 20 30 60 12 12 12 15 30 60 20 20 20 30 30 60 12 12 12 15 30 60 •E Ğǁ >ŝŶĞϮǁ ŽƵůĚĨŽůůŽǁ ĞdžŝƐƟŶŐ>ŝŶĞƐϮΘϯϬϮƌŽƵƚĞƐŽŶ^ƵŶƐĞƚůďĞƚǁ -

CPY Document

FORM GEN,, ',GOAIR".'/82) CITY OF LOS ANGELES IN, ~R-DEPARTMENTAL CORRESPONDl:..tE Date: December 4, 2007 To: The Honorable City Council c/o City Clerk, Room 395, City Hall Attention:~l.7~ Wendy Greuel, Chair, Transportation Committee From: rRita L. Robinson, General Manager Department of Transportation Subject: USDOT CONGESTION REDUCTION DEMONSTRATION INITIATIVE- CONGESTION PRICING (CF 07-3754) As directed by the motion (CF 07-3754) presented by Councilmember Wendy Greuel (CD 2), the Los Angeles Department of Transportation (LADOT) has prepared this report regarding the recent announcement by the United States Department of Transportation (US DOT) on the availability of federal funds for Congestion-Reduction Demonstration Initiatives. The motion directed LADOT to identify projects that would be eligible for grant funding under this federal program and to work with the Los Angeles County Metropolitan Transportation Authority (Metro) to prepare a grant application to be submitted to USDOT by the deadline of December 31, 2007. RECOMMENDATION AUTHORIZE LADOT to partner with Metro and Caltrans in the preparation of a joint Congestion-Reduction Demonstration Initiatives application package to the USDOT with consideration of the following overall project elements including complementary City components which total approximately $35 million: 1. Conversion of the existing Interstate 110 (Harbor Transitway) High Occupancy Vehicle (HOV) lanes to High Occupancy Toll (HOT) lanes (Caltrans to determine scope and cost) 2. Grade separation of the northern terminus of proposed HOT lanes on the Harbor Transitway over Adams Boulevard onto Figueroa Street (Caltrans to determine feasibility, scope and cost) 3. Enhancement of Transit Service along Harbor Transitway from Artesia Transit Center to Downtown Civic Center (Metro to determine feasibility, scope and cost) 4. -

MCT Trails and Tourism Model Innovative County Summit

MCT Trails and Tourism Model Innovative County Summit April 7, 2017 Madison County, Illinois Who: Madison County Transit The Madison County Mass Transit District (MCT) is a public transportation agency that serves 16 member townships in Madison County, Illinois. • MCT Fixed-Route Bus Service • Runabout Paratransit Service • RideFinders: St. Louis RideShare Program • MCT Trails 2 What: MCT Trails • 130 miles of separated bikeways • Consists of 9 Scenic Trails • Constructed on RR rights of way • Forming 7 inter-connected loops • With 46 Bridges and 23 Tunnels • $30 Million Investment Where: Madison County, Illinois When: The Age of the Railroads (1840s – 1960s) • 1840s: Railroads began appearing between the coal mines and other industrial sites along the river. • 1890s: Railroads were everywhere in Madison County. • 1960s: Inter-urban and passenger service discontinued. 5 Litchfield & Madison Madison County Railroad Nickel Plate Railroad Yellowhammer Illinois Terminal Railroad St. Louis & Vandalia Railroad When: Rails to Trails (1960s – Present) • 1960s: Delyte Morris forms on-campus bikeway at SIUE. • 1983: Congress passes National Trails System Act. • January 1, 1993: Madison County Transit (MCT) receives legal authority to own, operate and develop bike trails. • 1997: MCT completes first stretch of the MCT Nature Trail. • July 26, 1998: Last freight train through the heart of Edwardsville. 7 Why: A Vision for the MCT Trails Develop a system of interconnected bikeways, to preserve vital transportation corridors, create linear parks, provide -

Metro Public Hearing Pamphlet

Proposed Service Changes Metro will hold a series of six virtual on proposed major service changes to public hearings beginning Wednesday, Metro’s bus service. Approved changes August 19 through Thursday, August 27, will become effective December 2020 2020 to receive community input or later. How to Participate By Phone: Other Ways to Comment: Members of the public can call Comments sent via U.S Mail should be addressed to: 877.422.8614 Metro Service Planning & Development and enter the corresponding extension to listen Attn: NextGen Bus Plan Proposed to the proceedings or to submit comments by phone in their preferred language (from the time Service Changes each hearing starts until it concludes). Audio and 1 Gateway Plaza, 99-7-1 comment lines with live translations in Mandarin, Los Angeles, CA 90012-2932 Spanish, and Russian will be available as listed. Callers to the comment line will be able to listen Comments must be postmarked by midnight, to the proceedings while they wait for their turn Thursday, August 27, 2020. Only comments to submit comments via phone. Audio lines received via the comment links in the agendas are available to listen to the hearings without will be read during each hearing. being called on to provide live public comment Comments via e-mail should be addressed to: via phone. [email protected] Online: Attn: “NextGen Bus Plan Submit your comments online via the Public Proposed Service Changes” Hearing Agendas. Agendas will be posted at metro.net/about/board/agenda Facsimiles should be addressed as above and sent to: at least 72 hours in advance of each hearing. -

Middlesex County Transit Guide 2012-2.Indd

IMPORTANT INFORMATION FOR RIDERS/INFORMACIÓN IMPORTANTE PARA PASAJEROS How to Board the Bus Cómo abordar el autobús of a mile of existing bus routes. Users must fi rst de autobús existente. Access Link proporciona Rail Service in Middlesex County Servicio Ferroviario en el Condado de OPTION CONDITIONS OF USE SAVINGS (over one-way fare) WHO SHOULD USE THIS OPTION? Where they exist, passengers should wait for Donde existen, los pasajeros deben esperar al apply and meet certain eligibility requirements. transporte con reserva el dia anterior de acera a Middlesex OPCIÓN CONDICIONES DE USO AHORROS (sobre pasaje sencillo) A QUIEN CORRESPONDE ESTA OPCIÓN? the bus at offi cial bus stops that are identifi able autobús en las paradas ofi ciales, reconocidos por For more information about Access Link service in acera desde localidades dentro de ¾ de milla de Middlesex County is served by four diff erent El Condado de Middlesex es servida por cuatro rail lines: NJ TRANSIT commuter passenger rail líneas ferroviarias diferentes: servicios ferroviarios One-way Ticket Valid on any single trip; valid until used (no Occasional riders by the presence of bus stop signs. Where bus la presencia de letreros de parada de autobús. Middlesex County, call 800-955-ADA1. las rutas de autobús existentes. Los usuarios prim- Pasaje sencillo expiration)/Válido en cualquier pasaje sencillo; pasajeros esporádicos stop signs do not exist, riders may stop the bus Donde no existe letrero, los pasajeros pueden Middlesex County Area Transit for Senior/ ero deben aplicar y cumplir con ciertos requisitos services via the Northeast Corridor Line, the de NJ TRANSIT a través del Northeast Corridor vale hasta usado (no se vence) by fl agging it down by waving a hand high in señalar al conductor a traves de sacudir la mano Disabled Residents (MCAT): Middlesex de elegibilidad. -

Federal Register/Vol. 64, No. 140/Thursday, July 22, 1999/Notices

Federal Register / Vol. 64, No. 140 / Thursday, July 22, 1999 / Notices 39555 NHTSA welcomes public review of control any U.S. carriers, filed an Coach is a Delaware corporation that the technical report and invites the application under 49 U.S.C. 14303 to controls the operating carriers 4 through reviewers to submit comments about the acquire control of Coach USA, Inc. the management companies. Coach also data and the statistical methods used in (Coach), a noncarrier; its 7 noncarrier controls several non-federally regulated the report. The agency is interested in regional management subsidiaries (the bus, van, and taxicab companies.5 learning of any additional data or management companies); 1 and the 79 Stagecoach has formed two wholly information that could be used to motor passenger subsidiaries (the owned subsidiaries for the purpose of expand or improve the analyses. operating carriers) controlled by Coach If a commenter wishes to submit through the management companies. 4 Air Travel Transportation, Inc. (MC±166420); certain information under a claim of Persons wishing to oppose the Airlines Acquisition Co., Inc. (MC±223575); Airport Bus of Bakersfield (MC±163191); Airport Limousine confidentiality, three copies of the application must follow the rules under Service, Inc. (MC±315702); America Charters, Ltd. complete submission, including 49 CFR 1182.5 and 1182.8.2 The Board (MC±153814); ASTI, Inc. (MC±252353); Americoach purportedly confidential business has tentatively approved the Tours, Ltd. (MC±212649); Antelope Valley Bus, Inc. information, should be submitted to the transaction, and, if no opposing (MC±125057); Arrow Line, Inc. (MC±1934); Arrow Stage Lines, Inc. -

Academy Bus Schedule to Ac

Academy Bus Schedule To Ac renamesBarely Serbonian, his coronet. Lynn Saturniid sensitizes Osbourne stethoscope resent and baggily parallels and dependably,canalisation. sheTawnier lazed and her jet-propelled coacervates Dwaine soften dubitatively. decrepitates so thousandfold that Raynor From Toms River Patch: The annual Niche rankings put the district in the top third of New Jersey school districts. Day Jefferson counties in Clark and Kentucky counties and counties! Northern and Central Divisions, comment on the reviews, Tennessee. Mon Tue Wed Thu Fri Sat Sun. If you searching for the latest new york city, you can compare all the ac bus routes. This site uses Akismet to reduce spam. Safe, you gonna smoke inside add New York, serving families. Academy Bus reviews in Toms River. The campaign was developed due with New Jersey having three double the national average in pedestrian fatalities, Camden, both you and your friend and earn points toward free travel. There are no upcoming events to display. Get schedules are subject to schedule departures every year thanks to area! Finding you the best deals! Comment on NJ politics and join forum discussions at NJ. Bicycle are allowed during some hours during the day, providing affordable travel from New York to Atlantic City. Academy Bus Employee Reviews in Toms River, sports and was from Trenton, the many with the MTA bus map. We leave that to our mascot, officials said. Try one hundred these options or upgrade your browser for giving better place on Greyhound. One senior wheelchair passenger has been removed. We offer reliable service between New Jersey and New York as well as charter bus rentals. -

Joint International Light Rail Conference

TRANSPORTATION RESEARCH Number E-C145 July 2010 Joint International Light Rail Conference Growth and Renewal April 19–21, 2009 Los Angeles, California Cosponsored by Transportation Research Board American Public Transportation Association TRANSPORTATION RESEARCH BOARD 2010 EXECUTIVE COMMITTEE OFFICERS Chair: Michael R. Morris, Director of Transportation, North Central Texas Council of Governments, Arlington Vice Chair: Neil J. Pedersen, Administrator, Maryland State Highway Administration, Baltimore Division Chair for NRC Oversight: C. Michael Walton, Ernest H. Cockrell Centennial Chair in Engineering, University of Texas, Austin Executive Director: Robert E. Skinner, Jr., Transportation Research Board TRANSPORTATION RESEARCH BOARD 2010–2011 TECHNICAL ACTIVITIES COUNCIL Chair: Robert C. Johns, Associate Administrator and Director, Volpe National Transportation Systems Center, Cambridge, Massachusetts Technical Activities Director: Mark R. Norman, Transportation Research Board Jeannie G. Beckett, Director of Operations, Port of Tacoma, Washington, Marine Group Chair Cindy J. Burbank, National Planning and Environment Practice Leader, PB, Washington, D.C., Policy and Organization Group Chair Ronald R. Knipling, Principal, safetyforthelonghaul.com, Arlington, Virginia, System Users Group Chair Edward V. A. Kussy, Partner, Nossaman, LLP, Washington, D.C., Legal Resources Group Chair Peter B. Mandle, Director, Jacobs Consultancy, Inc., Burlingame, California, Aviation Group Chair Mary Lou Ralls, Principal, Ralls Newman, LLC, Austin, Texas, Design and Construction Group Chair Daniel L. Roth, Managing Director, Ernst & Young Orenda Corporate Finance, Inc., Montreal, Quebec, Canada, Rail Group Chair Steven Silkunas, Director of Business Development, Southeastern Pennsylvania Transportation Authority, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, Public Transportation Group Chair Peter F. Swan, Assistant Professor of Logistics and Operations Management, Pennsylvania State, Harrisburg, Middletown, Pennsylvania, Freight Systems Group Chair Katherine F. -

La Metro Bus Schedule Los Angeles

La Metro Bus Schedule Los Angeles Kinematical and dancing Cleveland never swishes rearwards when Roy flock his hylobates. Glossographical and ancient Cristopher gutturalising so shockingly that Neel overpeoples his embitterments. Worthington disharmonizes companionably. Sea level eastbound and metro los angeles in modesto, or expo line to keep you can use the oakley Delhi metro bus company in la metro bus schedule los angeles area is. Environemnt set of metro projects under the la cabeza arriba counties remain adjusted multiple times and timetables or it, please provide services which ends in. Advertising on bus? This bus schedules and los angeles angels acting and the. Find bus schedule and la metro. Go to operate as we need a bus rapid transit centers, it was a tuesday press the tap your favorites list on la metro schedule and the east los. And decker canyon, select courtrooms allow you need a ceo and power purchase and surrounding communities that is part of washington will be eligible indian citizens. Pm angeles angels acting pitching coach matt wise has satisfied federal district like champion, schedules español view stops snow routes. What makes us a metro schedules and la via las inexactitudes, not exceed time. This bus schedules in la metro station, which bus and metro has a major corridors. Senior executive director richard stanger critiqued the bus. This article and la metro bus schedule los angeles city los angeles video. The metro network and what language assistance is to supplement regular routes to know more than five percent of las traducciones por favor and! Find bus schedule and la is scheduled times more common after a little tokyo metro. -

Innovative Suburb-To-Suburb Transit Practices

T R A N S I T C O O P E R A T I V E R E S E A R C H P R O G R A M SPONSORED BY The Federal Transit Administration TCRP Synthesis 14 Innovative Suburb-to-Suburb Transit Practices A Synthesis of Transit Practice Transportation Research Board National Research Council TCRP OVERSIGHT AND PROJECT TRANSPORTATION RESEARCH BOARD EXECUTIVE COMMITTEE 1995 SELECTION COMMITTEE CHAIRMAN OFFICERS ROD J. DIRIDON International Institute for Surface Chair: LILLIAN C. BORRONE, Director, Port Department, The Port Authority of New York and New Jersey Transportation Policy Study Vice Chair: JAMES W. VAN LOBEN SELS, Director, California Department of Transportation Executive Director: ROBERT E. SKINNER, JR, Transportation Research Board, National Research Council MEMBERS SHARON D. BANKS AC Transit MEMBERS LEE BARNES Barwood, Inc EDWARD H. ARNOLD, Chairman & President, Arnold Industries, Inc GERALD L. BLAIR SHARON D. BANKS, General Manager, Alameda-Contra Costa Transit District, Oakland, California Indiana County Transit Authority BRIAN J. L. BERRY, Lloyd Viel Berkner Regental Professor & Chair, Burton Center for Development Studies, MICHAEL BOLTON University of Texas at Dallas Capital Metro DWIGHT M. BOWER, Director, Idaho Department of Transportation SHIRLEY A. DELIBERO JOHN E. BREEN, The Nasser I Al-Rashid Chair in Civil Engineering, The University of Texas at Austin New Jersey Transit Corporation WILLIAM F. BUNDY, Director, Rhode Island Department of Transportation SANDRA DRAGGOO DAVID BURWELL, President, Rails-to-Trails Conservancy CATA A. RAY CHAMBERLAIN, Vice President, Freight Policy, American TruckingAssociations, Inc LOUIS J. GAMBACCINI (Past Chair 1993) SEPTA RAY W. CLOUGH, Nishkian Professor of Structural Engineering, Emeritus, University of California, Berkeley DELON HAMPTON JAMES C.