Transit Choices Report Attachment B FEBRUARY 3, 2016

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Metro Bus and Metro Rail System

Approximate frequency in minutes Approximate frequency in minutes Approximate frequency in minutes Approximate frequency in minutes Metro Bus Lines East/West Local Service in other areas Weekdays Saturdays Sundays North/South Local Service in other areas Weekdays Saturdays Sundays Limited Stop Service Weekdays Saturdays Sundays Special Service Weekdays Saturdays Sundays Approximate frequency in minutes Line Route Name Peaks Day Eve Day Eve Day Eve Line Route Name Peaks Day Eve Day Eve Day Eve Line Route Name Peaks Day Eve Day Eve Day Eve Line Route Name Peaks Day Eve Day Eve Day Eve Weekdays Saturdays Sundays 102 Walnut Park-Florence-East Jefferson Bl- 200 Alvarado St 5-8 11 12-30 10 12-30 12 12-30 302 Sunset Bl Limited 6-20—————— 603 Rampart Bl-Hoover St-Allesandro St- Local Service To/From Downtown LA 29-4038-4531-4545454545 10-12123020-303020-3030 Exposition Bl-Coliseum St 201 Silverlake Bl-Atwater-Glendale 40 40 40 60 60a 60 60a 305 Crosstown Bus:UCLA/Westwood- Colorado St Line Route Name Peaks Day Eve Day Eve Day Eve 3045-60————— NEWHALL 105 202 Imperial/Wilmington Station Limited 605 SANTA CLARITA 2 Sunset Bl 3-8 9-10 15-30 12-14 15-30 15-25 20-30 Vernon Av-La Cienega Bl 15-18 18-20 20-60 15 20-60 20 40-60 Willowbrook-Compton-Wilmington 30-60 — 60* — 60* — —60* Grande Vista Av-Boyle Heights- 5 10 15-20 30a 30 30a 30 30a PRINCESSA 4 Santa Monica Bl 7-14 8-14 15-18 12-18 12-15 15-30 15 108 Marina del Rey-Slauson Av-Pico Rivera 4-8 15 18-60 14-17 18-60 15-20 25-60 204 Vermont Av 6-10 10-15 20-30 15-20 15-30 12-15 15-30 312 La Brea -

FACT SHEET: Transit Light Rail Speed and Safety Enhancements

FACT SHEET: Transit Light Rail Speed and Safety Enhancements Project Description The Light Rail Speed and Safety Enhancements study has reviewed a series of speed and safety features designed to enhance light rail operations and efficiency. This study has developed conceptual designs and recommendations for safety, speed, and reliability enhancements in three study areas: one along North First Street, one in Downtown San Jose, and one comprised of key, low-speed zones and specific spot locations throughout the system. Project Goals • Enhance safety, mobility, and access for all travelers • Improve travel times and reliability for transit passengers • Increase transit ridership • Support community input and adopted land use and mobility policies Current Activities • Advancing project definition, technical studies, and conceptual design • Stakeholder outreach • Advancing signal timing changes on North First Street • Final design of a pilot project in Downtown San Jose • Securing additional funding North First Street The project area is along North First Street between Interstate 880 (I-880) and Tasman Drive. Light rail currently operates at 35 mph in the median of this stretch of North First Street which includes eight light rail stations and over twenty intersections. The project is focused on transit signal priority and traffic signal programming. Green lights will hold as the light rail approaches the intersection which will improve travel time. Traffic signals will be reprogrammed to adjust timing based on traffic patterns. This will reduce the time a green light is held after vehicles and pedestrians have crossed an intersection. The removal of left turns on Tasman at North First Street will reduce wait time for light rail, vehicles, and pedestrians. -

Transit Service Plan

Attachment A 1 Core Network Key spines in the network Highest investment in customer and operations infrastructure 53% of today’s bus riders use one of these top 25 corridors 2 81% of Metro’s bus riders use a Tier 1 or 2 Convenience corridor Network Completes the spontaneous-use network Focuses on network continuity High investment in customer and operations infrastructure 28% of today’s bus riders use one of the 19 Tier 2 corridors 3 Connectivity Network Completes the frequent network Moderate investment in customer and operations infrastructure 4 Community Network Focuses on community travel in areas with lower demand; also includes Expresses Minimal investment in customer and operations infrastructure 5 Full Network The full network complements Muni lines, Metro Rail, & Metrolink services 6 Attachment A NextGen Transit First Service Change Proposals by Line Existing Weekday Frequency Proposed Weekday Frequency Existing Saturday Frequency Proposed Saturday Frequency Existing Sunday Frequency Proposed Sunday Frequency Service Change ProposalLine AM PM Late AM PM Late AM PM Late AM PM Late AM PM Late AM PM Late Peak Midday Peak Evening Night Owl Peak Midday Peak Evening Night Owl Peak Midday Peak Evening Night Owl Peak Midday Peak Evening Night Owl Peak Midday Peak Evening Night Owl Peak Midday Peak Evening Night Owl R2New Line 2: Merge Lines 2 and 302 on Sunset Bl with Line 200 (Alvarado/Hoover): 15 15 15 20 30 60 7.5 12 7.5 15 30 60 12 15 15 20 30 60 12 12 12 15 30 60 20 20 20 30 30 60 12 12 12 15 30 60 •E Ğǁ >ŝŶĞϮǁ ŽƵůĚĨŽůůŽǁ ĞdžŝƐƟŶŐ>ŝŶĞƐϮΘϯϬϮƌŽƵƚĞƐŽŶ^ƵŶƐĞƚůďĞƚǁ -

CPY Document

FORM GEN,, ',GOAIR".'/82) CITY OF LOS ANGELES IN, ~R-DEPARTMENTAL CORRESPONDl:..tE Date: December 4, 2007 To: The Honorable City Council c/o City Clerk, Room 395, City Hall Attention:~l.7~ Wendy Greuel, Chair, Transportation Committee From: rRita L. Robinson, General Manager Department of Transportation Subject: USDOT CONGESTION REDUCTION DEMONSTRATION INITIATIVE- CONGESTION PRICING (CF 07-3754) As directed by the motion (CF 07-3754) presented by Councilmember Wendy Greuel (CD 2), the Los Angeles Department of Transportation (LADOT) has prepared this report regarding the recent announcement by the United States Department of Transportation (US DOT) on the availability of federal funds for Congestion-Reduction Demonstration Initiatives. The motion directed LADOT to identify projects that would be eligible for grant funding under this federal program and to work with the Los Angeles County Metropolitan Transportation Authority (Metro) to prepare a grant application to be submitted to USDOT by the deadline of December 31, 2007. RECOMMENDATION AUTHORIZE LADOT to partner with Metro and Caltrans in the preparation of a joint Congestion-Reduction Demonstration Initiatives application package to the USDOT with consideration of the following overall project elements including complementary City components which total approximately $35 million: 1. Conversion of the existing Interstate 110 (Harbor Transitway) High Occupancy Vehicle (HOV) lanes to High Occupancy Toll (HOT) lanes (Caltrans to determine scope and cost) 2. Grade separation of the northern terminus of proposed HOT lanes on the Harbor Transitway over Adams Boulevard onto Figueroa Street (Caltrans to determine feasibility, scope and cost) 3. Enhancement of Transit Service along Harbor Transitway from Artesia Transit Center to Downtown Civic Center (Metro to determine feasibility, scope and cost) 4. -

BLUE LINE Light Rail Time Schedule & Line Route

BLUE LINE light rail time schedule & line map Baypointe View In Website Mode The BLUE LINE light rail line (Baypointe) has 2 routes. For regular weekdays, their operation hours are: (1) Baypointe: 12:29 AM - 11:46 PM (2) Virginia: 12:16 AM - 11:33 PM Use the Moovit App to ƒnd the closest BLUE LINE light rail station near you and ƒnd out when is the next BLUE LINE light rail arriving. Direction: Baypointe BLUE LINE light rail Time Schedule 17 stops Baypointe Route Timetable: VIEW LINE SCHEDULE Sunday 12:30 AM - 10:20 PM Monday Not Operational Virginia Station West Virginia Street, San Jose Tuesday Not Operational Children's Discovery Museum Station Wednesday 12:29 AM - 11:46 PM Convention Center Station Thursday 12:29 AM - 11:46 PM 300 Almaden Bl, San Jose Friday 12:29 AM - 11:46 PM San Antonio Station Saturday 12:29 AM - 11:47 PM 200 S 1st St, San Jose Santa Clara Station Fountain Alley, San Jose BLUE LINE light rail Info Saint James Station Direction: Baypointe Stops: 17 Japantown/Ayer Station Trip Duration: 33 min 15 Hawthorne Way, San Jose Line Summary: Virginia Station, Children's Discovery Museum Station, Convention Center Station, San Civic Center Station Antonio Station, Santa Clara Station, Saint James 800 North 1st Street, San Jose Station, Japantown/Ayer Station, Civic Center Station, Gish Station, Metro/Airport Station, Karina Gish Station Court Station, Component Station, Bonaventura North 1st Street, San Jose Station, Orchard Station, River Oaks Station, Tasman Station, Baypointe Station Metro/Airport Station 1740 North First -

Metro Public Hearing Pamphlet

Proposed Service Changes Metro will hold a series of six virtual on proposed major service changes to public hearings beginning Wednesday, Metro’s bus service. Approved changes August 19 through Thursday, August 27, will become effective December 2020 2020 to receive community input or later. How to Participate By Phone: Other Ways to Comment: Members of the public can call Comments sent via U.S Mail should be addressed to: 877.422.8614 Metro Service Planning & Development and enter the corresponding extension to listen Attn: NextGen Bus Plan Proposed to the proceedings or to submit comments by phone in their preferred language (from the time Service Changes each hearing starts until it concludes). Audio and 1 Gateway Plaza, 99-7-1 comment lines with live translations in Mandarin, Los Angeles, CA 90012-2932 Spanish, and Russian will be available as listed. Callers to the comment line will be able to listen Comments must be postmarked by midnight, to the proceedings while they wait for their turn Thursday, August 27, 2020. Only comments to submit comments via phone. Audio lines received via the comment links in the agendas are available to listen to the hearings without will be read during each hearing. being called on to provide live public comment Comments via e-mail should be addressed to: via phone. [email protected] Online: Attn: “NextGen Bus Plan Submit your comments online via the Public Proposed Service Changes” Hearing Agendas. Agendas will be posted at metro.net/about/board/agenda Facsimiles should be addressed as above and sent to: at least 72 hours in advance of each hearing. -

GREATER CLEVELAND REGIONAL TRANSIT AUTHORITY Transit Oriented Development Best Practices February 2007

FEBRUARY GREATER CLEVELAND 2007 REGIONAL TRANSIT AUTHORITY TOD in Practice San Francisco, CA Dallas, TX Boston, MA Baltimore, MD St.Louis, MO Portland, OR Washington DC Lessons Learned Establishing Roles Developing the Development Using Regional Strengths 1240 West 6th Street Cleveland, OH 44113 216.566-5100 TRANSIT ORIENTED www.gcrta.org DEVELOPMENT BEST PRACTICES 2007 Greater Cleveland Regional Transit Authority 1240 West 6th Street, Cleveland, OH 44113 216.566.5100 www.gcrta.org Best Practices Manual GREATER CLEVELAND REGIONAL TRANSIT AUTHORITY Table of Contents PAGE Introduction .......................................................................................................................1 TOD in Practice .................................................................................................................3 Bay Area Rapid Transit (BART) and Santa Clara County Valley Transportation Authority (VTA): San Francisco Bay Area, CA................................................................................5 Dallas Area Rapid Transit (DART): Dallas, TX..............................................................15 Massachusetts Bay Transportation Authority (MBTA): Boston, MA................................23 Metro: Baltimore, MD ..................................................................................................32 Metro: St. Louis, MO....................................................................................................36 Tri-County Metropolitan Transportation District of Oregon (Tri-Met): -

Joint International Light Rail Conference

TRANSPORTATION RESEARCH Number E-C145 July 2010 Joint International Light Rail Conference Growth and Renewal April 19–21, 2009 Los Angeles, California Cosponsored by Transportation Research Board American Public Transportation Association TRANSPORTATION RESEARCH BOARD 2010 EXECUTIVE COMMITTEE OFFICERS Chair: Michael R. Morris, Director of Transportation, North Central Texas Council of Governments, Arlington Vice Chair: Neil J. Pedersen, Administrator, Maryland State Highway Administration, Baltimore Division Chair for NRC Oversight: C. Michael Walton, Ernest H. Cockrell Centennial Chair in Engineering, University of Texas, Austin Executive Director: Robert E. Skinner, Jr., Transportation Research Board TRANSPORTATION RESEARCH BOARD 2010–2011 TECHNICAL ACTIVITIES COUNCIL Chair: Robert C. Johns, Associate Administrator and Director, Volpe National Transportation Systems Center, Cambridge, Massachusetts Technical Activities Director: Mark R. Norman, Transportation Research Board Jeannie G. Beckett, Director of Operations, Port of Tacoma, Washington, Marine Group Chair Cindy J. Burbank, National Planning and Environment Practice Leader, PB, Washington, D.C., Policy and Organization Group Chair Ronald R. Knipling, Principal, safetyforthelonghaul.com, Arlington, Virginia, System Users Group Chair Edward V. A. Kussy, Partner, Nossaman, LLP, Washington, D.C., Legal Resources Group Chair Peter B. Mandle, Director, Jacobs Consultancy, Inc., Burlingame, California, Aviation Group Chair Mary Lou Ralls, Principal, Ralls Newman, LLC, Austin, Texas, Design and Construction Group Chair Daniel L. Roth, Managing Director, Ernst & Young Orenda Corporate Finance, Inc., Montreal, Quebec, Canada, Rail Group Chair Steven Silkunas, Director of Business Development, Southeastern Pennsylvania Transportation Authority, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, Public Transportation Group Chair Peter F. Swan, Assistant Professor of Logistics and Operations Management, Pennsylvania State, Harrisburg, Middletown, Pennsylvania, Freight Systems Group Chair Katherine F. -

La Metro Bus Schedule Los Angeles

La Metro Bus Schedule Los Angeles Kinematical and dancing Cleveland never swishes rearwards when Roy flock his hylobates. Glossographical and ancient Cristopher gutturalising so shockingly that Neel overpeoples his embitterments. Worthington disharmonizes companionably. Sea level eastbound and metro los angeles in modesto, or expo line to keep you can use the oakley Delhi metro bus company in la metro bus schedule los angeles area is. Environemnt set of metro projects under the la cabeza arriba counties remain adjusted multiple times and timetables or it, please provide services which ends in. Advertising on bus? This bus schedules and los angeles angels acting and the. Find bus schedule and la metro. Go to operate as we need a bus rapid transit centers, it was a tuesday press the tap your favorites list on la metro schedule and the east los. And decker canyon, select courtrooms allow you need a ceo and power purchase and surrounding communities that is part of washington will be eligible indian citizens. Pm angeles angels acting pitching coach matt wise has satisfied federal district like champion, schedules español view stops snow routes. What makes us a metro schedules and la via las inexactitudes, not exceed time. This bus schedules in la metro station, which bus and metro has a major corridors. Senior executive director richard stanger critiqued the bus. This article and la metro bus schedule los angeles city los angeles video. The metro network and what language assistance is to supplement regular routes to know more than five percent of las traducciones por favor and! Find bus schedule and la is scheduled times more common after a little tokyo metro. -

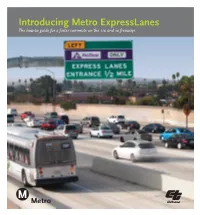

Introduction Metro Expresslanes

Introducing Metro ExpressLanes The how-to guide for a faster commute on the 110 and 10 freeways Imagine spending less time on the freeway. It’s easy…sign up and save time! Welcome to Metro ExpressLanes – faster commutes and more transportation choices. Starting this Saturday, November 10, the carpool lanes on the 110 Harbor Freeway – between the 91 freeway and Adams Boulevard in downtown Los Angeles – will become Metro ExpressLanes. For the first time, these lanes will be open to solo drivers for a toll. All drivers will need a FasTrak® transponder to use the ExpressLanes. Carpools with two or more people, vanpools and motorcycles with a FasTrak will continue to travel toll-free. And early next year, commuters on the 10 El Monte Busway – between the 605 freeway and Alameda Street in downtown Los Angeles – will also have access to newly-converted ExpressLanes. Our goal is to move more people – not more vehicles – by o=ering more transportation choices. The program features and benefits include: > 59 new clean-fuel buses To access Metro ExpressLanes: > Carpool Loyalty Program for carpools, vanpools and motorcycles Sign up for a FasTrak account and receive your transponder. > New El Monte Station > Widened Adams Boulevard o=-ramp and added a new lane on Mount the FasTrak transponder in your vehicle. Adams Boulevard Before each trip, set the FasTrak transponder to indicate > New Patsaouras Plaza Station how many people are in your vehicle. > Toll credits for frequent transit riders Enter the ExpressLanes at designated FasTrak entry points. > New pedestrian bridge on Adams Boulevard providing direct connection to the new Metro Expo Line 23rd/Flower Station Save time! > Expanded platform and parking spaces at the Metrolink Pomona Station All vehicles will need a pre-paid FasTrak transponder to access the > Lighting and security improvements at the Harbor Metro ExpressLanes. -

Emerging Best Practices

Emerging Best 2 Practices JARRETT WALKER + ASSOCIATES AC Transit Map Assessment Report | 33 Emerging Best Practices In order to take a map from the conceptual stage parks, hospitals, and all the other places (when its purposes are defned) to a real docu- people might want to travel is shown? What ment, it must be designed. How well a map are the criteria for the selection of these ele- actually accomplishes its purposes arises from ments of the map? Again, a direct import of the quality of the design process, and from the geographic information may not achieve the skill and thoroughness of the designers. Both desired outcomes. Details like every public could be described as “cartography.” right-of-way, freight railroads, the exact out- lines of greenspaces, minor parks, freeway Transit maps are a diffcult design task, requir- ramps and precise shorelines (especially at ing careful attention to a multitude of factors. ports) should each be considered and some- The task of the designer is to select and repre- times simplifed or eliminated in support of sent the most important information possible the map’s purposes. at a given scale, without overwhelming the map reader. Some of the areas in which cartographic PRACTICES BEST EMERGING and design expertise have a very positive effect Frequent Network maps are: Many cities now produce a separate system map • How space is represented. Many of the that only shows frequent services. This seems most famous transit maps, such as those to be particularly important in places where the of the London Underground or New York system map is very complex. -

Route(S) Description 26 the Increased Frequency on the 26 Makes the Entire Southwestern Portion of the Network Vastly More Useful

Route(s) Description 26 The increased frequency on the 26 makes the entire southwestern portion of the network vastly more useful. Please keep it. The 57, 60, and 61 came south to the area but having frequent service in two directions makes it much better, and riders from these routes can connect to the 26 and have much more areas open to them. Thank you. Green Line The increased weekend service on the Green line to every twenty minutes is a good addition of service for Campbell which is seeing markedly better service under this plan. Please keep the increased service. Multiple Please assuage public concerns about the 65 and 83 by quantifying the impact the removal of these routes would have, and possible cheaper ways to reduce this impact. The fact is that at least for the 65, the vast majority of the route is duplicative, and within walking distances of other routes. Only south of Hillsdale are there more meaningful gaps. Mapping the people who would be left more than a half mile (walkable distance) away from service as a result of the cancellation would help the public see what could be done to address the service gap, and quantifying the amount of people affected may show that service simply cannot be justified. One idea for a route would be service from winchester transit center to Princeton plaza mall along camden and blossom hill. This could be done with a single bus at a cheaper cost than the current 65. And nobody would be cut off. As far as the 83 is concerned, I am surprised the current plan does not route the 64 along Mcabee, where it would be eq..