Right to Asylum in Italy : Access to Procedures and Treatment of Asylum Seekers

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Avion Tourism Magazine

tourism AIRPORT MAGAZINE Complimentary copy by Milan-Bergamo Airport 54 2015 MarzoMarch MaggioMay - N. 54 MYKONOS PAN tELLERIA t OKYO Isola greca cosmopolita Suggestiva isola lavica La metropoli senza piazze POSTE ITALIANE SPA - Spedizione in A.P. - D.L. 353/2003 (conv. in L. 27/02/2004 n. 46) art. 1, comma 1, DCB Bergamo Marzo - Maggio Anno 13 in L. 27/02/2004 n. 46) art. 1, comma DCB Bergamo - D.L. 353/2003 (conv. - Spedizione in A.P. SPA POSTE ITALIANE Cosmopolitan island of Greece A spectacular volcanic island A city without squares 54 2015 MarzoMarch MaggioMay Ee ditorialeeditorial EditorE Publisher: sisterscom.com snc Via Piave, 102 - 23879 Verderio inferiore (lc) - italy Durante la primavera e l’estate il clima caldo e secco del Mediterraneo è l’ideale per trascorrere Tel. +39 039 8951335 - Tel. +39 035 19951510 - Fax +39 039 9121116 P.i. 03248170163 - www.sisterscom.com piacevoli vacanze al mare, ad esempio in una delle sue tante piccole e grandi incantevoli isole circondate da limpide acque turchesi. dirEttorE rEsponsabilE ediTor in ChieF Angela Trivigno - [email protected] Come Mykonos, l’isola trendy dell’arcipelago delle Cicladi, affascinante, con spiagge stupende, MarkEting E pubblicità MArkeTing & AdVerTising mare azzurro trasparente e intensa vita notturna. O santorini dall’aspetto del tutto singolare, con Annalisa Trivigno - [email protected] i forti contrasti del nero lavico delle rocce e il candore delle costruzioni di piccole case unifamiliari: RedazionE E ufficio staMpa ediToriAl Staff & Press OffiCe un’isola dal fascino romantico e dagli strabilianti colori. Oppure skiàthos, dove in ogni luogo aleggia [email protected]; [email protected] il profumo del mirto e si respira l’aria balsamica delle vaste pinete, che ne fanno un vero paradiso progEtto grafico E iMpaginazionE naturalistico, con ampie aree protette a ridosso delle spiagge. -

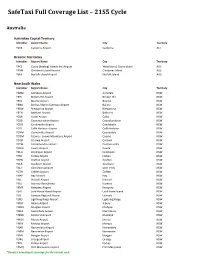

Safetaxi Full Coverage List – 21S5 Cycle

SafeTaxi Full Coverage List – 21S5 Cycle Australia Australian Capital Territory Identifier Airport Name City Territory YSCB Canberra Airport Canberra ACT Oceanic Territories Identifier Airport Name City Territory YPCC Cocos (Keeling) Islands Intl Airport West Island, Cocos Island AUS YPXM Christmas Island Airport Christmas Island AUS YSNF Norfolk Island Airport Norfolk Island AUS New South Wales Identifier Airport Name City Territory YARM Armidale Airport Armidale NSW YBHI Broken Hill Airport Broken Hill NSW YBKE Bourke Airport Bourke NSW YBNA Ballina / Byron Gateway Airport Ballina NSW YBRW Brewarrina Airport Brewarrina NSW YBTH Bathurst Airport Bathurst NSW YCBA Cobar Airport Cobar NSW YCBB Coonabarabran Airport Coonabarabran NSW YCDO Condobolin Airport Condobolin NSW YCFS Coffs Harbour Airport Coffs Harbour NSW YCNM Coonamble Airport Coonamble NSW YCOM Cooma - Snowy Mountains Airport Cooma NSW YCOR Corowa Airport Corowa NSW YCTM Cootamundra Airport Cootamundra NSW YCWR Cowra Airport Cowra NSW YDLQ Deniliquin Airport Deniliquin NSW YFBS Forbes Airport Forbes NSW YGFN Grafton Airport Grafton NSW YGLB Goulburn Airport Goulburn NSW YGLI Glen Innes Airport Glen Innes NSW YGTH Griffith Airport Griffith NSW YHAY Hay Airport Hay NSW YIVL Inverell Airport Inverell NSW YIVO Ivanhoe Aerodrome Ivanhoe NSW YKMP Kempsey Airport Kempsey NSW YLHI Lord Howe Island Airport Lord Howe Island NSW YLIS Lismore Regional Airport Lismore NSW YLRD Lightning Ridge Airport Lightning Ridge NSW YMAY Albury Airport Albury NSW YMDG Mudgee Airport Mudgee NSW YMER -

Lifting the Lid on Italy's Bluefin Tuna Fishery

Lifting the lid on Italy’s bluefin tuna fishery Assessment of compliance of Italy’s fishing fleets and farms with management rules during the 2008 bluefin tuna fishing season in the Mediterranean Report published by WWF Mediterranean & WWF Italy, October 2008 Summary This WWF-commissioned report, researched and compiled by independent consultancy ATRT, contains the first in-depth analysis of the role of Italy in the bluefin tuna fishery in the Mediterranean. Its findings confirm the widely held view that Italy is among the main culprits in the region for overfishing and violation of the fishery’s management rules. In April 2008 WWF released a report quantifying for the first time the fishing overcapacity of industrial fleets targeting the stock in the Mediterranean1. That study identified Italy as the leader in overcapacity among EU member states, with an estimated catch capacity for the industrial purse seine fleet twice the national quota allocated to it. The study pointed to the likely underreporting of real catches in the last years, coupled with a systematic violation of international management rules and the overshoot of national quotas. To ascertain the performance of the Italian bluefin tuna fishing industry during the crucial 2008 fishing season, the authors of this report have combined a thorough analysis of trade information with extensive field work. The latter has included the monitoring of Italy’s fleet at sea in real time, as well as the field analysis (through aerial surveys) of bluefin tuna biomass caged in every farm based in Italy, Croatia and Malta. This colossal undertaking has generated the most comprehensive picture yet of the role played by Italian interests in the Mediterranean bluefin tuna fishery, including the extent of compliance (or lack thereof) with international management rules agreed by the International Commission for the Conservation of Atlantic Tunas (ICCAT, the body tasked with sustainably managing the fishery) and the EU. -

2019 Committee on Civil Liberties

EUROPEAN PARLIAMENT 2014 - 2019 Committee on Civil Liberties, Justice and Home Affairs DRAFT MISSION REPORT of the EP LIBE delegation to Lampedusa (Italy) on search and rescue, in the context of the strategic own-initiative report on “the situation in the Mediterranean and the need for a holistic EU approach to migration” 17-18 September 2015 The LIBE Delegation on search and rescue to Lampedusa, Italy, on 17-18 September 2015 was composed of: MEMBERS Anna Maria CORAZZA BILDT EPP Head of delegation Kashetu KYENGE S&D Judith SARGENTINI Greens / ALE Ignazio CORRAO EFDD The delegation was authorised by the Conference of Presidents on 4 June 2015. 1. Introduction A delegation of four Members of the Committee on Civil Liberties, Justice and Home Affairs travelled to Italy from 17 to 18 September 2015 in order to gain a better understanding of search and rescue operations in the Mediterranean Sea. The delegation visited the Carlo Bergamini frigate, flagship of the Italian navy operation Mare Sicuro, currently deployed in the Mediterranean Sea, and the Phoenix vessel of the MOAS (Migrant Offshore Aid Station). Additionally, the delegation met with the mayor of Lampedusa, the international organisations and NGOs present in Lampedusa, the Guardia di Finanza (customs police) and Coast guard. The delegation witnessed the disembarkation of 50migrants who had been rescued at sea and their initial reception upon arrival at the pier in the harbour of Lampedusa. 2. Meeting with the mayor of Lampedusa, Ms Giusi Nicolini In the evening of the 17th of September, the delegation had an informal meeting with the Mayor of Lampedusa, Ms Giusi Nicolini. -

Avion Tourism Magazine Ha Raggiunto Il Tel

tourism AIRPORT M a G a Z i N e Complimentary copy by Milan Bergamo airport 60 2016 Settembreseptember NovembreNovember LOMBarDia sPeCiaLe Città d’arte DesTiNaZiONi Lombardy’s art cities special destinations 60 2016 Settembreseptember NovembreNovember ee DITORIALeeDITORIAL editore PuBlisher: sisterscom.com snc via Piave, 102 - 23879 verderio inferiore (lc) - italy questa è un’uscita speciale, perché avion Tourism Magazine ha raggiunto il Tel. +39 039 8951335 - Tel. +39 035 19951510 - Fax +39 039 9121116 60esimo numero! Per festeggiare questa importante tappa vogliamo condividere P.i. 03248170163 - www.sisterscom.com con tutti i nostri affezionati lettori e viaggiatori, che arrivano o partono direttore responsabile eDiTor in ChieF dall’Aeroporto di Milano Bergamo, tutti i successi che hanno accompagnato angela Trivigno - [email protected] in tanti anni la crescita esponenziale dell’aeroporto, diventato il terzo scalo marketinG e pubblicitÀ MarKeTinG & aDverTisinG italiano per traffico passeggeri. Per chi arriva all’Aeroporto di Milano Bergamo, annalisa Trivigno - [email protected] WWW.AVIONTOURISM.COM in questo numero troverà uno speciale dedicato alle splendide città lombarde, tutte a pochi chilometri redazione e ufficio stampa eDiTorial sTaFF & Press oFFiCe di distanza e assolutamente da visitare come Bergamo, Brescia, Como, Cremona, Lecco, Mantova, Milano, [email protected] Monza, Pavia, Sirmione o Vigevano che vantano ciascuna un patrimonio artistico peculiare e rinomato proGetto Grafico e impaGinazione GraPhiC DesiGn anD PaGinG in tutto il mondo. sisterscom.com Invece, per chi parte, abbiamo voluto non privilegiare nessuna meta specifica, dando invece spazio a tutte traduzioni TranslaTions le destinazioni offerte dall’aeroporto, attraverso una corposa ed emblematica galleria fotografica che Juliet halewood racchiude i paesi collegati, le città raggiunte, i tempi di percorrenza, le compagnie aeree che effettuano collaboratori ConTriBuTors il servizio con la relativa frequenza dei voli e il contatto per le informazioni turistiche. -

Interventi Ing 2019.Qxp INTERVENTI

2_Safety 2019.qxp_LA SAFETY 03/06/19 08:59 Pagina 56 Sheet 2.3 Organisations oversight ORGANISATIONS OVERSIGHT In accordance with national and international standards, products, to verify compliance with certification SAFETY oversight activities are carried out by ENAC based on a requirements and monitor technical and/or operational National Oversight Program of Certified Organisations processes. through two main types of inspections: Inspections, so-called “deep cut” inspections on a Audits, formal programmed and unplanned inspections particular topic or activity, both on land and in flight, conducted on organizations, infrastructures, staff, programmed and unplanned, possibly even equipment, documentation, procedures, processes and unannounced. Approved organisations as of 31/12 2016 2017 2018 ADR Airports open to commercial traffic 45 43 43 ANSP Air Navigation Service Provider 7 7 7 POA Production Organisation Approval (Part 21 subpart F) - Production Organisations without certification privilege 6 4 4 POA Production Organisation Approval (Part 21 subpart G) - Production Organisations with certification privilege 49 52 54 AMO Approved Maintenance Organisation (Part 145) - Maintenance Organisations of aircraft classified as “Large aircraft” or used for Commercial Air Transport and/or their components 134 128 133 AMTO Approved Maintenance Training organisation (Part 147) Training organisations for technical personnel operating in maintenance organisations 15 14 15 AMO Approved Maintenance Organisation (PART M Subpart F) - Maintenance -

Albastar Announces Its Summer Schedule of Flights Departing from Milan Bergamo Airport

PRESS RELEASE AlbaStar announces its summer schedule of flights departing from Milan Bergamo Airport. AlbaStar announces its summer 2021 schedule of flights departing from Milan Bergamo Airport, with a series of weekly and twice-weekly connections to the Italian islands (Lampedusa, Sardinia and Sicily) and southern Italy (Calabria and Apulia), and an international destination, Porto Santo, in the Madeira archipelago. Flights departing from Milan Bergamo Airport: Porto Santo, every Friday, from 4 June to 24 September. Alghero, every Saturday, from 5 June to 25 September. Cagliari, every Saturday, from 5 June to 25 September. Olbia, every Saturday, from 5 June to 25 September. Lamezia Terme, every Saturday, from 5 June to 25 September. Crotone, every Saturday, from 5 June to 25 September. Lampedusa, every Saturday from 29 May to 2 October, and every Sunday from 30 May to 3 October. Brindisi, every Sunday, from 6 June to 26 September. Catania, every Sunday, from 6 June to 26 September. “We are pleased to be able to offer a significant summer schedule from our operational base at Milan Bergamo, where in recent years we have been a point of reference as a leisure carrier, as a result of our consolidated cooperation with the Sacbo airport management company and our partner tour operators. Our objective is to expand the network as soon as changes in the restrictions applied during the health emergency make it possible to plan new destinations, so that we can return to our normal schedule of operations, serving all the destinations that we have had to temporarily suspend or reduce in frequency”, said Giancarlo Celani, Sales Director & Deputy CEO at AlbaStar. -

Airport Regulation

BALANCE HEADQUARTERS Viale Castro Pretorio, 118 • 00185 Rome Ph. +39 06 44596-1 • Fax +39 06 44596493 www.enac.gov.it PRESIDENT Vito Riggio BOARD Andrea Corte Lucio d’Alessandro Roberto Serrentino ACCOUNT ADVISORY BOARD Paolo Castaldi (President) Andrea Bertoncini Dino Poli DIRECTOR GENERAL Alessio Quaranta Editorial Coordination Maria Pastore Head of Institutional Communication Unit With the collaboration of Maria Elena Taormina Director of Personnel & Development Dept. Supervisor of Trasparency Francesca Miceli Andrea Pirola Institutional Communication Unit Acknowledgements We would like to thank all of ENAC's Depts. for their collaboration Graphic design, translation and printing: Cantieri Creativi Srl Printed in May 2015 REPORT AND SOCIAL BALANCE ITALIANCIVILAVIATIONAUTHORITY Contributions Vito Riggio President of the Italian Civil Aviation Authority 2014: a positive year for European civil aviation 3 Alessio Quaranta Director General of the Italian Civil Aviation Authority The new regulatory framework 13 Benedetto Marasà Deputy Director General of the Italian Civil Aviation Authority Flight safety in 2014 16 Patrick Ky Executive Director of the European Aviation Safety Agency EASA: status, role and scope of activities 20 ENAC REPORT AND SOCIAL BALANCE 2014 CONTRIBUTIONS President of the Italian Civil Aviation Authority 2014: a positive year for European civil aviation he past year has been a positive one for European civil aviation. Despite an increase in traffic which signals the start of the recovery after the long crisis that began in 2008, the accident rates have remained constant T in comparison to those of 2013, a year that we remember as the best in the shared history of our sector. It is a parameter built upon millions of hours of flight, that amounts to exactly one accident with victims every 8 million flights. -

Financial Statements 2013

Financial Statements 2013 FINANCIAL STATEMENTS CONSOLIDATED FINANCIAL STATEMENT 2013 Bilancio ENAV S.P.A. VIA SALARIA, 716 00138 ROMA www.enav.it Financial Statements 2013 FINANCIAL STATEMENTS CONSOLIDATED FINANCIAL STATEMENT Index ORGANS AND OFFICIAL ROLES OF ENAV S.P.A. 5 REPORT ON OPERATIONS 7 › Profile of ENAV S.p.A. and of the Group 8 › Corporate Governance 9 › Management key areas 10 › Market trends 22 › Commercial activities in domestic and foreign third markets 25 › Investments and research 27 › Environment 33 › Human resources 35 › Other information 41 › Economic trend and financial situation of Enav and of the group 47 › Risk factors 55 › Relation with the related parties 60 › Significant facts at the closing of the fiscal year 62 › Performance Forecast 63 › Proposal for allocation of net profits of Enav S.p.A. 65 FINANCIAL STATEMENTS OF ENAV S.P.A. ON DECEMBER 31 2013 67 Notes to the financial statements 73 › Section 1: Form and content of the technical statements 74 › Section 2: Basis of preparation of the financial statements and accounting policies 75 › Section 3: Analysis of balance sheet items and their changes 80 › Section 4: Further information 115 › Annexes 117 › Certification of the CEO and the Manager in charge 127 › Report of the Supervisory Board 129 › Report of the independent auditors 137 CONSOLIDATED FINANCIAL STATEMENTS OF THE ENAV GROUP ON 31 DECEMBER 2013 141 Notes to the consolidated financial statements 147 › Section 1: Form and content of the consolidated financial statements 148 › Section 2: Group valuation criteria 151 › Section 3: Analysis of balance sheet items and their charge 156 › Section 4: Further information 171 › Annexes 173 › Certification of the CEO and the Manager in charge 183 › Report of the Supervisory Board 185 › Report of the independent auditors 190 Glossary 194 ENAV FINANCIAL STATEMENTS – 2013 3 4 ENAV FINANCIAL STATEMENTS – 2013 Organs and official roles of ENAV S.P.A. -

Progress Report on Aircraft Noise Abatement in Europe V3

Interest Group on Traffic Noise Abatement European Network of the Heads of Environment Protection Agencies (EPA Network ) Progress report on aircraft noise abatement in Europe v3 Berlin, Maastricht | July 2015 Colophon Project management Dr. Kornel Köstli, Dr. Hans Bögli (Swiss Federal Office for the Environment) Prepared for Interest Group on Traffic Noise Abatement (IGNA) Members of the IGNA National Institute for the Environment of Poland (chair) Swiss Federal Office for the Environment (co-chair) German Federal Environment Agency Danish Protection Agency European Environment Agency Regional Authority for Public Health National Institute for the Environment of Denmark Norwegian Climate and Pollution Agency Environmental Agency of the Republic of Slovenia Malta Environment & Planning Authority National Research Institute of Environmental Protection Italian Institute for Environmental Protection and Research National Institute for Public Health and the Environment RIVM CENIA, Czech Environmental Information Agency Environment Agency Austria Title Progress report on aircraft noise abatement in Europe v3 Report No. M+P.BAFU.14.01.1 Revision 2 Date July 2015 Pages 66 Authors Dr. Gijsjan van Blokland Contact Gijsjan van Blokland | +31 (0)73-6589050 | [email protected] M+P Wolfskamerweg 47 Vught | PO box 2094, 5260 CB Vught Visserstraat 50 Aalsmeer | PO box 344, 1430 AH Aalsmeer www.mplusp.eu | part of Müller -BBM group | member of NLingenieurs | ISO 9001 certified Copyright © M+P raadgevende ingenieurs BV | No part of this publication may be used for purposes other than agreed upon by client and M+P (DNR 2011 Art. 46). Executive Summary This report describes the present situation and future developments with regard to aircraft noise in the European region. -

KODY LOTNISK ICAO Niniejsze Zestawienie Zawiera 8372 Kody Lotnisk

KODY LOTNISK ICAO Niniejsze zestawienie zawiera 8372 kody lotnisk. Zestawienie uszeregowano: Kod ICAO = Nazwa portu lotniczego = Lokalizacja portu lotniczego AGAF=Afutara Airport=Afutara AGAR=Ulawa Airport=Arona, Ulawa Island AGAT=Uru Harbour=Atoifi, Malaita AGBA=Barakoma Airport=Barakoma AGBT=Batuna Airport=Batuna AGEV=Geva Airport=Geva AGGA=Auki Airport=Auki AGGB=Bellona/Anua Airport=Bellona/Anua AGGC=Choiseul Bay Airport=Choiseul Bay, Taro Island AGGD=Mbambanakira Airport=Mbambanakira AGGE=Balalae Airport=Shortland Island AGGF=Fera/Maringe Airport=Fera Island, Santa Isabel Island AGGG=Honiara FIR=Honiara, Guadalcanal AGGH=Honiara International Airport=Honiara, Guadalcanal AGGI=Babanakira Airport=Babanakira AGGJ=Avu Avu Airport=Avu Avu AGGK=Kirakira Airport=Kirakira AGGL=Santa Cruz/Graciosa Bay/Luova Airport=Santa Cruz/Graciosa Bay/Luova, Santa Cruz Island AGGM=Munda Airport=Munda, New Georgia Island AGGN=Nusatupe Airport=Gizo Island AGGO=Mono Airport=Mono Island AGGP=Marau Sound Airport=Marau Sound AGGQ=Ontong Java Airport=Ontong Java AGGR=Rennell/Tingoa Airport=Rennell/Tingoa, Rennell Island AGGS=Seghe Airport=Seghe AGGT=Santa Anna Airport=Santa Anna AGGU=Marau Airport=Marau AGGV=Suavanao Airport=Suavanao AGGY=Yandina Airport=Yandina AGIN=Isuna Heliport=Isuna AGKG=Kaghau Airport=Kaghau AGKU=Kukudu Airport=Kukudu AGOK=Gatokae Aerodrome=Gatokae AGRC=Ringi Cove Airport=Ringi Cove AGRM=Ramata Airport=Ramata ANYN=Nauru International Airport=Yaren (ICAO code formerly ANAU) AYBK=Buka Airport=Buka AYCH=Chimbu Airport=Kundiawa AYDU=Daru Airport=Daru -

Annual Report 2015

ANNUAL REPORT 2015 CATEGORY WINNER 10-25 MILLION PASSENGERS CONTENTS GENERAL INFORMATION 04 The SEA Group ______________________________________________________________ 06 Structure of the SEA Group and investments in other companies _____________________ 07 Corporate Boards ____________________________________________________________ 09 Key financial indicators at December 31, 2015 _____________________________________ 010 2015 DIRECTORS’ REPORT _____________________________________________________ 012 Economic overview __________________________________________________________ 014 Regulatory framework ________________________________________________________ 017 Performance of the SEA Group _________________________________________________ 019 Quantitative traffic data ___________________________________________________ 019 Income Statement _______________________________________________________ 020 Reclassified Balance Sheet _________________________________________________ 024 Reclassified Cash Flow Statement ___________________________________________ 025 SEA Group investments _______________________________________________________ 029 FY2015: significant events _____________________________________________________ 030 Significant events subsequent to year end _______________________________________ 032 Outlook ____________________________________________________________________ 033 Operating Performance – Industry Analysis _______________________________________ 034 Commercial Aviation ______________________________________________________