Download: Brill.Com/Brill-Typeface

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Epic Imagination in Contemporary Indian Literature

University of South Florida Scholar Commons Graduate Theses and Dissertations Graduate School May 2017 Modern Mythologies: The picE Imagination in Contemporary Indian Literature Sucheta Kanjilal University of South Florida, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarcommons.usf.edu/etd Part of the South and Southeast Asian Languages and Societies Commons Scholar Commons Citation Kanjilal, Sucheta, "Modern Mythologies: The pE ic Imagination in Contemporary Indian Literature" (2017). Graduate Theses and Dissertations. http://scholarcommons.usf.edu/etd/6875 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Modern Mythologies: The Epic Imagination in Contemporary Indian Literature by Sucheta Kanjilal A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy with a concentration in Literature Department of English College of Arts and Sciences University of South Florida Major Professor: Gurleen Grewal, Ph.D. Gil Ben-Herut, Ph.D. Hunt Hawkins, Ph.D. Quynh Nhu Le, Ph.D. Date of Approval: May 4, 2017 Keywords: South Asian Literature, Epic, Gender, Hinduism Copyright © 2017, Sucheta Kanjilal DEDICATION To my mother: for pencils, erasers, and courage. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS When I was growing up in New Delhi, India in the late 1980s and the early 1990s, my father was writing an English language rock-opera based on the Mahabharata called Jaya, which would be staged in 1997. An upper-middle-class Bengali Brahmin with an English-language based education, my father was as influenced by the mythological tales narrated to him by his grandmother as he was by the musicals of Broadway impressario Andrew Lloyd Webber. -

Abhinavagupta's Portrait of a Guru: Revelation and Religious Authority in Kashmir

Abhinavagupta's Portrait of a Guru: Revelation and Religious Authority in Kashmir The Harvard community has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters Citable link http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:39987948 Terms of Use This article was downloaded from Harvard University’s DASH repository, and is made available under the terms and conditions applicable to Other Posted Material, as set forth at http:// nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:dash.current.terms-of- use#LAA Abhinavagupta’s Portrait of a Guru: Revelation and Religious Authority in Kashmir A dissertation presented by Benjamin Luke Williams to The Department of South Asian Studies in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the subject of South Asian Studies Harvard University Cambridge, Massachusetts August 2017 © 2017 Benjamin Luke Williams All rights reserved. Dissertation Advisor: Parimal G. Patil Benjamin Luke Williams ABHINAVAGUPTA’S PORTRAIT OF GURU: REVELATION AND RELIGIOUS AUTHORITY IN KASHMIR ABSTRACT This dissertation aims to recover a model of religious authority that placed great importance upon individual gurus who were seen to be indispensable to the process of revelation. This person-centered style of religious authority is implicit in the teachings and identity of the scriptural sources of the Kulam!rga, a complex of traditions that developed out of more esoteric branches of tantric "aivism. For convenience sake, we name this model of religious authority a “Kaula idiom.” The Kaula idiom is contrasted with a highly influential notion of revelation as eternal and authorless, advanced by orthodox interpreters of the Veda, and other Indian traditions that invested the words of sages and seers with great authority. -

Mumbai Macbeth: Gender and Identity in Bollywood Adaptations Rashmila Maiti University of Arkansas, Fayetteville

University of Arkansas, Fayetteville ScholarWorks@UARK Theses and Dissertations 8-2018 Mumbai Macbeth: Gender and Identity in Bollywood Adaptations Rashmila Maiti University of Arkansas, Fayetteville Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarworks.uark.edu/etd Part of the Asian Studies Commons, Comparative Literature Commons, and the Literature in English, British Isles Commons Recommended Citation Maiti, Rashmila, "Mumbai Macbeth: Gender and Identity in Bollywood Adaptations" (2018). Theses and Dissertations. 2905. http://scholarworks.uark.edu/etd/2905 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by ScholarWorks@UARK. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UARK. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Mumbai Macbeth: Gender and Identity in Bollywood Adaptations A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Comparative Literature and Cultural Studies by Rashmila Maiti Jadavpur University Bachelor of Arts in English Literature, 2007 Jadavpur University Master of Arts in English Literature, 2009 August 2018 University of Arkansas This dissertation is approved for recommendation to the Graduate Council. M. Keith Booker, PhD Dissertation Director Yajaira M. Padilla, PhD Frank Scheide, PhD Committee Member Committee Member Abstract This project analyzes adaptation in the Hindi film industry and how the concepts of gender and identity have changed from the original text to the contemporary adaptation. The original texts include religious epics, Shakespeare’s plays, Bengali novels which were written pre- independence, and Hollywood films. This venture uses adaptation theory as well as postmodernist and postcolonial theories to examine how women and men are represented in the adaptations as well as how contemporary audience expectations help to create the identity of the characters in the films. -

MAY 2020 Weekly Activities 2 Dear Friends, Going Green J.O.Y

Capen Caller Newsletter West Bridgewater Council On Aging 97 West Center Street, West Bridgewater MA 02379 508-894-1262 Bruce Holmquist, Chairman of the Board * Marilyn Mather, Director LOOK WHAT’S INSIDE MAY 2020 Weekly Activities 2 Dear Friends, Going Green J.O.Y. Sign-up Sometimes in the darkest of hours if we look hard enough we see a little glimmer of JOY. On Wednesday April 29th our little glimmer came to us in the form of a Early Voting 3 parade of cars driven by our J.O.Y. (Just Older Youth) members and friends tooting Musical Instrument their horns, waving and yelling “THANK YOU” to the COA staff joined by West Word Search Bridgewater Board of Selectmen Anthony Kinahan, Denise Reyes, Eldon Moreira and Town Manager David Gagne! Thank you to Marguerite Morse and to all who Lunch Menu 4 Comedy Movies planned and participated in this fabulous gesture of caring and appreciation. We Word Search love you and miss you all. As time marches on we are now in the midst of planning and preparing for when May Birthdays 5 the time comes to phase in programs and activities. This will be a very slow and careful process, but we will keep you posted as we move forward. Board of Directors 6 Staff & Volunteers Stay home, stay safe and remember we are here Monday - Friday 9:00AM - 3:00PM Community Caring to answer questions and to offer assistance if you have needs or concerns. The Meals On Wheels program is still running and our van drivers are available to take you grocery shopping (call ahead). -

Abhinavagupta's Theory of Relection a Study, Critical Edition And

Abhinavagupta’s Theory of Relection A Study, Critical Edition and Translation of the Pratibimbavāda (verses 1-65) in Chapter III of the Tantrāloka with the commentary of Jayaratha Mrinal Kaul A Thesis In the Department of Religion Presented in Partial Fulilment of the Requirements For the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Religion) at Concordia University Montréal, Québec, Canada August 2016 © Mrinal Kaul, 2016 CONCORDIA UNIVERSITY School of Graduate Studies This is to certify that the thesis prepared By: Mrinal Kaul Entitled: Abhinavagupta’s Theory of Relection: A Study, Critical Edition and Translation of the Pratibimbavāda (verses 1-65) in Chapter III of the Tantrāloka with the commentary of Jayaratha and submitted in partial fulillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Religion) complies with the regulations of the University and meets the accepted standards with respect to originality and quality. Signed by the inal Examining Committee: _____________________________Chair Dr Christine Jourdan _____________________________External Examiner Dr Richard Mann _____________________________External to Programme Dr Stephen Yeager _____________________________Examiner Dr Francesco Sferra _____________________________Examiner Dr Leslie Orr _____________________________Supervisor Dr Shaman Hatley Approved by ____________________________________________________________ Dr Carly Daniel-Hughes, Graduate Program Director September 16, 2016 ____________________________________________ Dr André Roy, Dean Faculty of Arts and Science ABSTRACT Abhinavagupta’s Theory of Relection: A Study, Critical Edition and Translation of the Pratibimbavāda (verses 1-65) in the Chapter III of the Tantrāloka along with the commentary of Jayaratha Mrinal Kaul, Ph.D. Religion Concordia University, 2016 The present thesis studies the theory of relection (pratibimbavāda) as discussed by Abhinavagupta (l.c. 975-1025 CE), the non-dualist Trika Śaiva thinker of Kashmir, primarily focusing on what is often referred to as his magnum opus: the Tantrāloka. -

Issues in Indian Philosophy and Its History

4 ISSUESININDIAN PHILOSOPHY AND ITS HISTORY 4.1 DOXOGRAPHY AND CATEGORIZATION Gerdi Gerschheimer Les Six doctrines de spéculation (ṣaṭtarkī) Sur la catégorisation variable des systèmes philosophiques dans lInde classique* ayam eva tarkasyālaņkāro yad apratişţhitatvaņ nāma (Śaģkaraad Brahmasūtra II.1.11, cité par W. Halbfass, India and Europe, p. 280) Les sixaines de darśana During the last centuries, the six-fold group of Vaiśeşika, Nyāya, Sāņkhya, Yoga, Mīmāņ- sā, and Vedānta ( ) hasgained increasing recognition in presentations of Indian philosophy, and this scheme of the systems is generally accepted today.1 Cest en effet cette liste de sys- tèmes philosophiques (darśana) quévoque le plus souvent, pour lindianiste, le terme şađ- darśana. Il est cependant bien connu, également, que le regroupement sous cette étiquette de ces six systèmes brahmaniques orthodoxes est relativement récent, sans doute postérieur au XIIe siècle;2 un survol de la littérature doxographique sanskrite fait apparaître quil nest du reste pas le plus fréquent parmi les configurations censées comprendre lensemble des sys- tèmes.3 La plupart des doxographies incluent en effet des descriptions des trois grands sys- tèmes non brahmaniques, cest-à-dire le matérialisme,4 le bouddhisme et le jaïnisme. Le Yoga en tant que tel et le Vedānta,par contre, sont souvent absents de la liste des systèmes, en particulier avant les XIIIe-XIVe siècles. Il nen reste pas moins que les darśana sont souvent considérés comme étant au nombre de six, quelle quen soit la liste. La prégnance de cette association, qui apparaît dès la première doxographie, le fameux Şađdarśanasamuccaya (Compendium des six systèmes) du jaina Haribhadra (VIIIe s. -

Madhya Bharti 75 21.07.18 English

A Note on Paradoxes and Some Applications Ram Prasad At times thoughts in prints, dialogues, conversations and the likes create illusion among people. There may be one reason or the other that causes fallacies. Whenever one attempts to clear the illusion to get the logical end and is unable to, one may slip into the domain of paradoxes. A paradox seemingly may appear absurd or self contradictory that may have in fact a high sense of thought. Here a wide meaning of it including its shades is taken. There is a group of similar sensing words each of which challenges the wit of an onlooker. A paradox sometimes surfaces as and when one is in deep immersion of thought. Unprinted or oral thoughts including paradoxes can rarely survive. Some paradoxes always stay folded to gaily mock on. In deep immersion of thought W S Gilbert remarks on it in the following poetic form - How quaint the ways of paradox At common sense she gaily mocks1 The first student to expect great things of Philosophy only to suffer disillusionment was Socrates (Sokratez) -'what hopes I had formed and how grievously was I disappointed'. In the beginning of the twentieth century mathematicians and logicians rigidly argued on topics which appear possessing intuitively valid but apparently contrary statements. At times when no logical end is seen around and the topic felt hot, more on lookers would enter into these entanglements with argumentative approach. May be, but some 'wise' souls would manage to escape. Zeno's wraths - the Dichotomy, the Achilles, the Arrow and the Stadium made thinkers very uncomfortable all along. -

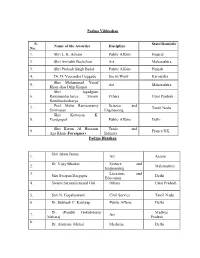

Padma Vibhushan S. No. Name of the Awardee Discipline State/Domicile

Padma Vibhushan S. State/Domicile Name of the Awardee Discipline No. 1. Shri L. K. Advani Public Affairs Gujarat 2. Shri Amitabh Bachchan Art Maharashtra 3. Shri Prakash Singh Badal Public Affairs Punjab 4. Dr. D. Veerendra Heggade Social Work Karnataka Shri Mohammad Yusuf 5. Art Maharashtra Khan alias Dilip Kumar Shri Jagadguru 6. Ramanandacharya Swami Others Uttar Pradesh Rambhadracharya Prof. Malur Ramaswamy Science and 7. Tamil Nadu Srinivasan Engineering Shri Kottayan K. 8. Venugopal Public Affairs Delhi Shri Karim Al Hussaini Trade and 9. France/UK Aga Khan ( Foreigner) Industry Padma Bhushan Shri Jahnu Barua 1. Art Assam Dr. Vijay Bhatkar Science and 2. Maharashtra Engineering 3. Literature and Shri Swapan Dasgupta Delhi Education 4. Swami Satyamitranand Giri Others Uttar Pradesh 5. Shri N. Gopalaswami Civil Service Tamil Nadu 6. Dr. Subhash C. Kashyap Public Affairs Delhi Dr. (Pandit) Gokulotsavji Madhya 7. Art Maharaj Pradesh 8. Dr. Ambrish Mithal Medicine Delhi 9. Smt. Sudha Ragunathan Art Tamil Nadu 10. Shri Harish Salve Public Affairs Delhi 11. Dr. Ashok Seth Medicine Delhi 12. Literature and Shri Rajat Sharma Delhi Education 13. Shri Satpal Sports Delhi 14. Shri Shivakumara Swami Others Karnataka Science and 15. Dr. Kharag Singh Valdiya Karnataka Engineering Prof. Manjul Bhargava Science and 16. USA (NRI/PIO) Engineering 17. Shri David Frawley Others USA (Vamadeva) (Foreigner) 18. Shri Bill Gates Social Work USA (Foreigner) 19. Ms. Melinda Gates Social Work USA (Foreigner) 20. Shri Saichiro Misumi Others Japan (Foreigner) Padma Shri 1. Dr. Manjula Anagani Medicine Telangana Science and 2. Shri S. Arunan Karnataka Engineering 3. Ms. Kanyakumari Avasarala Art Tamil Nadu Literature and Jammu and 4. -

Paninian Studies

The University of Michigan Center for South and Southeast Asian Studies MICHIGAN PAPERS ON SOUTH AND SOUTHEAST ASIA Ann Arbor, Michigan STUDIES Professor S. D. Joshi Felicitation Volume edited by Madhav M. Deshpande Saroja Bhate CENTER FOR SOUTH AND SOUTHEAST ASIAN STUDIES UNIVERSITY OF MICHIGAN Number 37 Open access edition funded by the National Endowment for the Humanities/ Andrew W. Mellon Foundation Humanities Open Book Program. Library of Congress catalog card number: 90-86276 ISBN: 0-89148-064-1 (cloth) ISBN: 0-89148-065-X (paper) Copyright © 1991 Center for South and Southeast Asian Studies The University of Michigan Printed in the United States of America ISBN 978-0-89148-064-8 (hardcover) ISBN 978-0-89148-065-5 (paper) ISBN 978-0-472-12773-3 (ebook) ISBN 978-0-472-90169-2 (open access) The text of this book is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ CONTENTS Preface vii Madhav M. Deshpande Interpreting Vakyapadiya 2.486 Historically (Part 3) 1 Ashok Aklujkar Vimsati Padani . Trimsat . Catvarimsat 49 Pandit V. B. Bhagwat Vyanjana as Reflected in the Formal Structure 55 of Language Saroja Bhate On Pasya Mrgo Dhavati 65 Gopikamohan Bhattacharya Panini and the Veda Reconsidered 75 Johannes Bronkhorst On Panini, Sakalya, Vedic Dialects and Vedic 123 Exegetical Traditions George Cardona The Syntactic Role of Adhi- in the Paninian 135 Karaka-System Achyutananda Dash Panini 7.2.15 (Yasya Vibhasa): A Reconsideration 161 Madhav M. Deshpande On Identifying the Conceptual Restructuring of 177 Passive as Ergative in Indo-Aryan Peter Edwin Hook A Note on Panini 3.1.26, Varttika 8 201 Daniel H. -

Gorinski2018.Pdf

This thesis has been submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for a postgraduate degree (e.g. PhD, MPhil, DClinPsychol) at the University of Edinburgh. Please note the following terms and conditions of use: This work is protected by copyright and other intellectual property rights, which are retained by the thesis author, unless otherwise stated. A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge. This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the author. The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the author. When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given. Automatic Movie Analysis and Summarisation Philip John Gorinski I V N E R U S E I T H Y T O H F G E R D I N B U Doctor of Philosophy Institute for Language, Cognition and Computation School of Informatics University of Edinburgh 2017 Abstract Automatic movie analysis is the task of employing Machine Learning methods to the field of screenplays, movie scripts, and motion pictures to facilitate or enable vari- ous tasks throughout the entirety of a movie’s life-cycle. From helping with making informed decisions about a new movie script with respect to aspects such as its origi- nality, similarity to other movies, or even commercial viability, all the way to offering consumers new and interesting ways of viewing the final movie, many stages in the life-cycle of a movie stand to benefit from Machine Learning techniques that promise to reduce human effort, time, or both. -

PDF (V. 86:13, January 18, 1985)

THE CALIFORNIA VOLUME 86 PASADENA, CALIFORNIA I FRIDAY, JANUARY 18, 1985 NUMBER 13 SURF Applications Marcus Wins Now Available Wolf Prize by Lily Wu made during the school year to by Lily Wu The Summer Undergraduate groups such as the Caltech Alum Rudolph A. Marcus, the Noyes Research Fellowship (SURF) ap ni Board and an IBM technical Professor ofChemistry at Caltech, plications are now available for the group. Also, a total of 41 papers will be awarded the $100,000 Wolf summer. have been published by SURFers Prize in Chemistry for 1984-85. The SURF program is and their sponsors as a result of Marcus was selected in operating this year with additional their research project work. recognition ofhis career-long con contributions and a new ad Later this month, a two-time tributions to chemical kinetics. He ministrative committee. SURFer, Tak Leuk Kwok helped to pioneer work iri reaction Last April, President Marvin (1982,1983) will receive the Apker rate theories with the RRKM Goldberger created a new Ad Award from the American Physical theory in 1951, which he ministrative Committee for SURF. Society. The national prize will be co-authored. The committee is chaired by Pro awarded to Kwok for the most pro Marcus also worked on models fessor Fred Shair and it includes 15 mising undergraduate research in <: to describe molecular break-up members of the faculty and ad physics, which he performed in a ~:;, rates of uni-molecular reactions ministration. The purpose for the surf. ~ and electron transfer reactions. committee is to plan and administer The stipends for this year will ~ Such information helps chemists SURF every year, as well as to again be $2800. -

Historical Continuity and Colonial Disruption

8 Historical Continuity and Colonial Disruption major cause of the distortions discussed in the foregoing chapters A has been the lack of adequate study of early texts and pre-colonial Indian thinkers. Such a study would show that there has been a historical continuity of thought along with vibrant debate, controversy and innovation. A recent book by Jonardan Ganeri, the Lost Age of Reason: Philosophy in Early Modern India 1450-1700, shows this vibrant flow of Indian thought prior to colonial times, and demonstrates India’s own variety of modernity, which included the use of logic and reasoning. Ganeri draws on historical sources to show the contentious nature of Indian discourse. He argues that it did not freeze or reify, and that such discourse was established well before colonialism. This chapter will show the following: • There has been a notion of integral unity deeply ingrained in the various Indian texts from the earliest times, even when they 153 154 Indra’s Net offer diverse perspectives. Indian thought prior to colonialism exhibited both continuity and change. A consolidation into what we now call ‘Hinduism’ took place prior to colonialism. • Colonial Indology was driven by Europe’s internal quest to digest Sanskrit and its texts into European history without contradicting Christian monotheism. Indologists thus selectively appropriated whatever Indian ideas fitted into their own narratives and rejected what did not. This intervention disrupted the historical continuity of Indian thought and positioned Indologists as the ‘pioneers’. • Postmodernist thought in many ways continues this digestion and disruption even though its stated purpose is exactly the opposite.