Speaking Back: Queerness, Temporality, and the Irish Voice in America

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Celebrations-Issue-12-DV05768.Pdf

Enjoy the magic of Walt Disney World all year long with Celebrations magazine! Receive 6 issues for $29.99* (save more than 15% off the cover price!) *U.S. residents only. To order outside the United States, please visit www.celebrationspress.com. To subscribe to Celebrations magazine, clip or copy the coupon below. Send check or money order for $29.99 to: YES! Celebrations Press Please send me 6 issues of PO Box 584 Celebrations magazine Uwchland, PA 19480 Name Confirmation email address Address City State Zip You can also subscribe online at www.celebrationspress.com. On the Cover: “Miss Tilly”, photo by Barrie Brewer Issue 12 Exploring 42 Contents Typhoon Lagoon and Letters ..........................................................................................6 Blizzard Beach Calendar of Events ............................................................ 8 Disney News & Updates..................................................9 MOUSE VIEWS ..........................................................13 Guide to the Magic by Tim Foster............................................................................14 The Old Swimmin’ Explorer Emporium by Lou Mongello .....................................................................16 Hole: River Country 52 Hidden Mickeys by Steve Barrett ......................................................................18 Photography Tips & Tricks by Tim Devine .........................................................................20 Pin Trading & Collecting by John Rick .............................................................................22 -

This Was a Time of Both Turmoil and Prosperity for America

Lillie, Disney, 1 Cleansing the Past, Selling the Future: Disney’s Corporate Exhibits at the 1964-65 New York World’s Fair Jonathan J. M. Lillie JOMC 242 History Paper 5/3/02 Park Doctoral Fellow The School of Journalism and Mass Communication The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill Lillie, Disney, 2 Abstract This paper offers a historical analysis of Disney’s corporate exhibits at the 1964-65 New York World’s Fair, GE’s “Carousel of Progress” and Ford’s “Magic Skyway,” in an attempt to consider their historical and cultural significance. The coming together of Disney’s legacy of nostalgic entertainment achieved via his desire and skill in “improving” the past and future with the equally strong desire of corporate giants to sell themselves and their products is presented here as a case study of the processes of cultural creation: how and why specific discourses of technology and consumption are written in to these narratives of the past and the future. Introduction Between April 22, 1964 and October 17, 1965 fifty-one million people experienced the New York World’s Fair.1 The mid-1960s was a time of both turmoil and prosperity for America. President Kennedy had been assassinated only months before the Fair’s opening. In southern states such as Alabama the civil rights protest movement was drawing national attention. While cold war tensions remained high following the Cuban Missile Crisis, the nation was enjoying the height of postwar economic prosperity and geo-political power. The Fair’s twin themes of “Man’s Achievements in an Expanding Universe” and “A Millennium of Progress” captured the exuberance of the times, celebrating “the boundless potential of science and technology for human betterment.”2 The 1939 New York World’s Fair was in many ways a predecessor to the 1964-65 exhibition. -

Goldy Gets Studious College Support Helps Gopher Athletics Shine

FALL 2009 Goldy gets studious COLLEGE SUPPORT HELPS GOPHER ATHLETICS SHINE 2008-2009 DONOR REPORT connect Dear friends, Vol. 4, No. 1 • Fall 2009 AUTUMN IS ALWAYS AN EXCITING TIME at the EDITOR University of Minnesota. The campus explodes with students Diane L. Cormany walking, riding bikes, or skateboarding. The air is crackling 612-626-5650, [email protected] with excitement, especially from our incoming students, ART DIRECTOR/DESIGNER whose spirit re-energizes us for the busy months to come. Nance Longley Welcome Class of 2013! DESIGN ASSISTANT Bethany Dick This year is electrifying as we welcome Gopher football WRITERS back to campus—an event with particular resonance for the Diane L. Cormany, Suzy Frisch, Kate Hopper, College of Education and Human Development. Our college Brigitt Martin, Heather Peña, Roxi Rejali, Kara Rose, Lynn Slifer, Andrew Tellijohn plays a critical role in supporting Gophers as athletes and as students. School of Kinesiology Director Mary Jo Kane led University efforts PHOTOGRAPHERS Andrea Canter, Greg Helgeson, Leo Kim, that reshaped how student athletes are supported academically. Jeanne Higbee in Patrick O’Leary, Dawn Villella the Department of Postsecondary Teaching and Learning teaches all incoming ONLINE EDITION Gopher athletes the academic and life skills they need to juggle demands in the cehd.umn.edu/pubs/connect gym or on the field with their primary responsibility to get a top-notch education. OFFICE OF THE DEAN Jean Quam, interim dean Most of our students strike that balance. For example, Heather Dorniden, a David R. Johnson, senior dean senior in kinesiology, is an eight-time All American track and field athlete, the Heidi Barajas, associate dean Mary Trettin, associate dean winner of the President’s Student Leadership and Service Award, and has a 3.90 Lynn Slifer, director of external relations GPA. -

Community Outlet Editorial Director Name Ed. Dir. Email Address Ed

Community Outlet Editorial Director Ed. Dir. Email Ed. Dir. Phone Name Address Number African African Network Inza Dosso africvisiontv@yahoo. 646-505-9952 Television com; mmustaf25@yahoo. com African African Sun Times Abba Onyeani africansuntimes@gma973-280-8415 African African-American Steve Mallory blacknewswatch@ao 718-598-4772 Observer l.com African Afrikanspot Isseu Diouf Campbell [email protected] 917-204-1582 om African Afro Heritage Olutosin Mustapha [email protected] 718-510-5575 Magazine om African Afro Times African Afrobeat Radio / Wuyi Jacobs submissions@afrobe 347-559-6570 WBAI 99.5 FM atradio.com African Amandla Kofi Ayim kayim@amandlanew 973-731-1339 s.com African Sunu Afrik Radio El Hadji Ndao [email protected] 646-505-7487 m; sunuafrikradio@gma il.com African American Black and Brown Sharon Toomer info@blackandbrow 917-721-3150 News nnews.com African American Diaspora Radio Pearl Phillip [email protected] 718-771-0988 African American Harlem World Eartha Watts Hicks; harlemworldinfo@ya 646-216-8698 Magazine Danny Tisdale hoo.com African American New York Elinor Tatum elinor.tatum@amste 212-932-7465 Amsterdam News rdamnews.com; info@amsterdamne ws.com African American New York Beacon Miatta Smith nybeaconads@yaho 212-213-8585 o.com African American Our Time Press David Greaves editors@ourtimepre 718-599-6828 ss.com African American The Black Star News Milton Allimadi [email protected] 646-261-7566 m African American The Network Journal Rosalind McLymont [email protected] 212-962-3791 ; [email protected] Albanian Illyria Ruben Avxhiu [email protected] 212-868-2224 om; [email protected] m Arab Allewaa Al-Arabi Angie Damlaki angie_damlakhi@ya 646-707-2012 hoo.com Arab Arab Astoria Abdul Azmal arabastoria@yahoo. -

Andrew Farrell Magenheim

P a g e 1 9 / IRISH ECHO FIRST RESPONDERS AWARDS I r i s h E c h o / N O V 2018 Recipient of The Michael J Fahy E M B E R 7 - Profile in Bravery Award 1 3 , 2 0 1 8 / w w w . i r i s h e c h o . c o m Andrew Farrell Magenheim I celebrate my Irish heritage by: I am a member of the FDNY Emerald Place of Birth: New York, NY society and take part in the annual Saint Patrick's Day parade in Manhattan. Job Description: I am a lieutenant with the New York City Fire Department. My grandfather, married to an Irish citizen and is second generation himself. I am currently assigned to the third division in Manhattan and work in Ladder He proudly sold the Irish Echo at his news stand in the East Village for over 26 in East Harlem. While at work, I am responsible for supervising a crew forty years. I also reside in Pearl River, NY and take my family to the parade of 5 firefighters. I spent the first 10 years of my career on Morris Avenue in in town every year. the South Bronx, and I have worked in Manhattan for the last two years. Three things people would be surprised to know about me: Why I chose this career: My mother's side of the family had many family 1. I hold an electrical engineering degree from Cornell University members that were part of the FDNY. When I was growing up, I would 2. -

American Book Awards 2004

BEFORE COLUMBUS FOUNDATION PRESENTS THE AMERICAN BOOK AWARDS 2004 America was intended to be a place where freedom from discrimination was the means by which equality was achieved. Today, American culture THE is the most diverse ever on the face of this earth. Recognizing literary excel- lence demands a panoramic perspective. A narrow view strictly to the mainstream ignores all the tributaries that feed it. American literature is AMERICAN not one tradition but all traditions. From those who have been here for thousands of years to the most recent immigrants, we are all contributing to American culture. We are all being translated into a new language. BOOK Everyone should know by now that Columbus did not “discover” America. Rather, we are all still discovering America—and we must continue to do AWARDS so. The Before Columbus Foundation was founded in 1976 as a nonprofit educational and service organization dedicated to the promotion and dissemination of contemporary American multicultural literature. The goals of BCF are to provide recognition and a wider audience for the wealth of cultural and ethnic diversity that constitutes American writing. BCF has always employed the term “multicultural” not as a description of an aspect of American literature, but as a definition of all American litera- ture. BCF believes that the ingredients of America’s so-called “melting pot” are not only distinct, but integral to the unique constitution of American Culture—the whole comprises the parts. In 1978, the Board of Directors of BCF (authors, editors, and publishers representing the multicultural diversity of American Literature) decided that one of its programs should be a book award that would, for the first time, respect and honor excellence in American literature without restric- tion or bias with regard to race, sex, creed, cultural origin, size of press or ad budget, or even genre. -

Enjoy the Magic of Walt Disney World All Year Long with Celebrations Magazine! Receive 6 Issues for $29.99* (Save More Than 15% Off the Cover Price!) *U.S

Enjoy the magic of Walt Disney World all year long with Celebrations magazine! Receive 6 issues for $29.99* (save more than 15% off the cover price!) *U.S. residents only. To order outside the United States, please visit www.celebrationspress.com. To subscribe to Celebrations magazine, clip or copy the coupon below. Send check or money order for $29.99 to: YES! Celebrations Press Please send me 6 issues of PO Box 584 Celebrations magazine Uwchland, PA 19480 Name Confirmation email address Address City State Zip You can also subscribe online at www.celebrationspress.com. On the Cover: “Splash!”, photo by Tim Devine Issue 24 Taking the Plunge on 42 Contents Splash Mountain Letters ..........................................................................................6 Calendar of Events ............................................................ 8 Disney News & Updates................................................10 MOUSE VIEWS ......................................................... 15 Guide to the Magic O Canada by Tim Foster............................................................................16 50 Explorer Emporium by Lou Mongello .....................................................................18 Hidden Mickeys by Steve Barrett .....................................................................20 Photography Tips & Tricks by Tim Devine .........................................................................22 Music in the Parks Pin Trading & Collecting by John Rick .............................................................................24 -

Monthly Program Synopsis: Disney Women Animators and the History of Cartooning February 26, 2019, MH Library

Monthly Program Synopsis: Disney Women Animators and the History of Cartooning February 26, 2019, MH Library Suman Ganapathy VP Programs, Yvonne Randolph introduced museum educator from the Walt Disney Museum, Danielle Thibodeau, in her signature vivacious style. It was followed by a fascinating and educational presentation by Thibodeau about women animators and their role in the history of cartooning as presented in the Disney Family Museum located in the Presidio, San Francisco. The talk began with a short history of the museum. The museum, which opened in 2009, was created by one of Walt Disney’s daughters, Diane Disney Miller. After discovering shoeboxes full of Walt Disney’s Oscar awards at the Presidio, Miller started a project to create a book about her father, but ended up with the museum instead. Disney’s entire life is presented in the museum’s interactive galleries, including his 248 awards, early drawings, animation, movies, music etc. His life was inspirational. Disney believed that failure helped an individual grow, and Thibodeau said that Disney always recounted examples from his own life where he never let initial failures stop him from reaching his goals. The history of cartooning is mainly the history of Walt Dissey productions. What was achieved in his studios was groundbreaking and new, and it took many hundreds of people to contribute to its success. The Nine Old Men: Walt Disney’s core group of animators were all white males, and worked on the iconic Disney movies, and received more than their share of encomium and accolades. The education team of the Walt Disney museum decided to showcase the many brilliant and under-appreciated women who worked at the Disney studios for the K-12 students instead. -

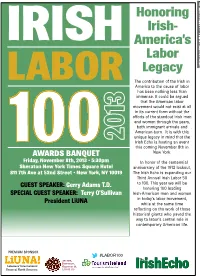

Irishecholabor100magazine

Page 17 Honoring / Irish Echo / NOVEMBER 6 - 12, 2013 / www.irishecho.com Irish- IRISH America’s Labor Legacy LABOR The contribution of the Irish in America to the cause of labor has been nothing less than immense. It could be argued that the American labor 3 movement would not exist at all 1 in its current form without the efforts of the standout Irish men and women through the years, 0 both immigrant arrivals and American-born. It is with this unique legacy in mind that the 2 Irish Echo is hosting an event this coming November 8th in AWARDS BANQUET New York. Friday, November 8th, 2013 • 5:30pm In honor of the centennial Sheraton New York Times Square Hotel anniversary of the 1913 lockout, 811 7th Ave at 52nd Street • New York, NY 10019 The Irish Echo is expanding our Third Annual Irish Labor 50 GUEST SPEAKER: Gerry Adams T.D. to 100. This year we will be honoring 100 leading SPECIAL GUEST SPEAKER: Terry O’Sullivan Irish-American men and women in today’s labor movement, President LiUNA while at the same time reflecting on the work of those historical giants who paved the way to labor’s central role in contemporary American life. PREMIUM SPONSOR #LABOR100 The ARCHER, BYINGTON, Laborers’ International GLENNON & IrishEcho Union of North America LEVINE LLP Page Page 18 IRISH LABOR 100 The Irish gave life to American labor By Terry O'Sullivan and leading various labor organizations. [email protected] For many of these warriors of the working class, their work is more than a n this centennial year of the historic job, and larger than a career; it is a Dublin Lockout, it is fitting that we lifetime's commitment. -

New York New Belfast Conference 2019 P

CHARITY PARTNER 8 1 e g a New York New Belfast Conference 2019 P / 9 1 0 2 , 8 1 - 2 1 E N U All the very best from Belfast J / o A chairde The Belfast Agenda – our targeted community h c plan - has ambitions to see a Belfast reimagined, E h s At my recent installation as Lord Mayor of Belfast, I well-connected, culturally vibrant, and a magnet for i r I spoke of my determination to build on the economic talent. And whilst building our city for its citizens, / prosperity essential to supporting peace and driving those ambitions provide a wealth of opportunities for m o c forward progress. our partners in North America and, as we have . o h That prosperity has been bolstered by the very already seen, in the beating heart of New York. c e h transatlantic partnerships that bring you together One of the many friends of Belfast, Tom diNapoli – s i r i here at the tenth New York New Belfast conference. and this year a New York New Belfast Be The Bridge . w w Forged by our community champions, in honouree – has as State Comptroller for New York w business, arts and culture, the relationships between State, explored those avenues of opportunity. With our great cities thrive and flourish in this investments in the city currently totalling (30 million environment. This is where the talking begins, where dollars) his commitment highlights the city’s the discussion and debates grow, on how our aspiration and ambition as well as its steady growth camaraderie and connections translate into mutually and success. -

Introduction Interpreting Irish America1

Chapter 1 Introduction Interpreting Irish America1 J. J. Lee Ireland has had one of the most extraordinary histories in the world. Winston Churchill would bear unlikely witness in exhorting the House of Commons on 15 December 1921 to accept the Anglo-Irish Treaty by asking them: Whence does this mysterious power of Ireland come? It is a small, poor, sparsely popu- lated island, lapped about by British sea power, accessible on every side, without iron or coal. How is it that she sways our councils, shakes our parties and infects us with her bit- terness, convulses our passions and deranges our actions? How is it that she has forced generation after generation to stop the whole traffic of the British Empire in order to debate her domestic affairs?2 Churchill’s own answer was that “Ireland is not a daughter race. She is a parent na- tion.” This was, of course, a heavily coded message. Although Churchill himself pur- ported to be talking about the Irish in the British Empire, what he meant even more was that it was in the interests of England’s relations with America for it to make some concessions to Irish demands for independence. His listeners in the House of Commons knew perfectly well he meant that those for whom she was mainly “the parent nation” were the American Irish and that they were playing a crucial role in the struggle for independence. Eighty years later Peter Quinn could still observe that “Ire- land remains a canvas on which many of the broad brush strokes of the modern world’s formation—imperialism, colonialism, nationalism, revolution, emigration, democratization, et al.—can be fruitfully studied and examined.”3 This Irish background is crucial to an understanding of the historical role of the American Irish, however much that role may be adapting to the changing circum- stances of the present. -

Identity and Authenticity: Explorations in Native American and Irish Literature and Culture

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Dissertations, Theses, and Student Research: Department of English English, Department of April 2006 Identity and Authenticity: Explorations in Native American and Irish Literature and Culture Drucilla M. Wall University of Nebraska-Lincoln Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/englishdiss Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Wall, Drucilla M., "Identity and Authenticity: Explorations in Native American and Irish Literature and Culture" (2006). Dissertations, Theses, and Student Research: Department of English. 3. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/englishdiss/3 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the English, Department of at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations, Theses, and Student Research: Department of English by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. Identity and Authenticity: Explorations in Native American and Irish Literature and Culture by Drucilla Mims Wall A Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of The Graduate College of the University of Nebraska In Partial Fulfillment of Requirements For the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Major: English Under the Supervision of Professor Jonis Agee Lincoln, Nebraska May, 2006 ii Abstract IDENTITY AND AUTHENTICITY: EXPLORATIONS IN NATIVE AMERICAN AND IRISH LITERATURE AND CULTURE Drucilla Mims Wall, Ph.D. University of Nebraska-Lincoln, 2006 Advisor: Jonis Agee This collection explores of some of the many ways in which Native American, Irish, and immigrant Irish-American cultures negotiate the complexities of how they are represented as "other," and how they represent themselves, through the literary and cultural practices and productions that define identity and construct meaning.