This Was a Time of Both Turmoil and Prosperity for America

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Celebrations-Issue-12-DV05768.Pdf

Enjoy the magic of Walt Disney World all year long with Celebrations magazine! Receive 6 issues for $29.99* (save more than 15% off the cover price!) *U.S. residents only. To order outside the United States, please visit www.celebrationspress.com. To subscribe to Celebrations magazine, clip or copy the coupon below. Send check or money order for $29.99 to: YES! Celebrations Press Please send me 6 issues of PO Box 584 Celebrations magazine Uwchland, PA 19480 Name Confirmation email address Address City State Zip You can also subscribe online at www.celebrationspress.com. On the Cover: “Miss Tilly”, photo by Barrie Brewer Issue 12 Exploring 42 Contents Typhoon Lagoon and Letters ..........................................................................................6 Blizzard Beach Calendar of Events ............................................................ 8 Disney News & Updates..................................................9 MOUSE VIEWS ..........................................................13 Guide to the Magic by Tim Foster............................................................................14 The Old Swimmin’ Explorer Emporium by Lou Mongello .....................................................................16 Hole: River Country 52 Hidden Mickeys by Steve Barrett ......................................................................18 Photography Tips & Tricks by Tim Devine .........................................................................20 Pin Trading & Collecting by John Rick .............................................................................22 -

The Theme Park As "De Sprookjessprokkelaar," the Gatherer and Teller of Stories

University of Central Florida STARS Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019 2018 Exploring a Three-Dimensional Narrative Medium: The Theme Park as "De Sprookjessprokkelaar," The Gatherer and Teller of Stories Carissa Baker University of Central Florida, [email protected] Part of the Rhetoric Commons, and the Tourism and Travel Commons Find similar works at: https://stars.library.ucf.edu/etd University of Central Florida Libraries http://library.ucf.edu This Doctoral Dissertation (Open Access) is brought to you for free and open access by STARS. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019 by an authorized administrator of STARS. For more information, please contact [email protected]. STARS Citation Baker, Carissa, "Exploring a Three-Dimensional Narrative Medium: The Theme Park as "De Sprookjessprokkelaar," The Gatherer and Teller of Stories" (2018). Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019. 5795. https://stars.library.ucf.edu/etd/5795 EXPLORING A THREE-DIMENSIONAL NARRATIVE MEDIUM: THE THEME PARK AS “DE SPROOKJESSPROKKELAAR,” THE GATHERER AND TELLER OF STORIES by CARISSA ANN BAKER B.A. Chapman University, 2006 M.A. University of Central Florida, 2008 A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the College of Arts and Humanities at the University of Central Florida Orlando, FL Spring Term 2018 Major Professor: Rudy McDaniel © 2018 Carissa Ann Baker ii ABSTRACT This dissertation examines the pervasiveness of storytelling in theme parks and establishes the theme park as a distinct narrative medium. It traces the characteristics of theme park storytelling, how it has changed over time, and what makes the medium unique. -

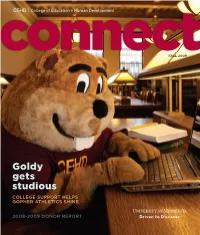

Goldy Gets Studious College Support Helps Gopher Athletics Shine

FALL 2009 Goldy gets studious COLLEGE SUPPORT HELPS GOPHER ATHLETICS SHINE 2008-2009 DONOR REPORT connect Dear friends, Vol. 4, No. 1 • Fall 2009 AUTUMN IS ALWAYS AN EXCITING TIME at the EDITOR University of Minnesota. The campus explodes with students Diane L. Cormany walking, riding bikes, or skateboarding. The air is crackling 612-626-5650, [email protected] with excitement, especially from our incoming students, ART DIRECTOR/DESIGNER whose spirit re-energizes us for the busy months to come. Nance Longley Welcome Class of 2013! DESIGN ASSISTANT Bethany Dick This year is electrifying as we welcome Gopher football WRITERS back to campus—an event with particular resonance for the Diane L. Cormany, Suzy Frisch, Kate Hopper, College of Education and Human Development. Our college Brigitt Martin, Heather Peña, Roxi Rejali, Kara Rose, Lynn Slifer, Andrew Tellijohn plays a critical role in supporting Gophers as athletes and as students. School of Kinesiology Director Mary Jo Kane led University efforts PHOTOGRAPHERS Andrea Canter, Greg Helgeson, Leo Kim, that reshaped how student athletes are supported academically. Jeanne Higbee in Patrick O’Leary, Dawn Villella the Department of Postsecondary Teaching and Learning teaches all incoming ONLINE EDITION Gopher athletes the academic and life skills they need to juggle demands in the cehd.umn.edu/pubs/connect gym or on the field with their primary responsibility to get a top-notch education. OFFICE OF THE DEAN Jean Quam, interim dean Most of our students strike that balance. For example, Heather Dorniden, a David R. Johnson, senior dean senior in kinesiology, is an eight-time All American track and field athlete, the Heidi Barajas, associate dean Mary Trettin, associate dean winner of the President’s Student Leadership and Service Award, and has a 3.90 Lynn Slifer, director of external relations GPA. -

Alan Lomax: Selected Writings 1934-1997

ALAN LOMAX ALAN LOMAX SELECTED WRITINGS 1934–1997 Edited by Ronald D.Cohen With Introductory Essays by Gage Averill, Matthew Barton, Ronald D.Cohen, Ed Kahn, and Andrew L.Kaye ROUTLEDGE NEW YORK • LONDON Published in 2003 by Routledge 29 West 35th Street New York, NY 10001 www.routledge-ny.com Published in Great Britain by Routledge 11 New Fetter Lane London EC4P 4EE www.routledge.co.uk Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group. This edition published in the Taylor & Francis e-Library, 2005. “To purchase your own copy of this or any of Taylor & Francis or Routledge’s collection of thousands of eBooks please go to www.eBookstore.tandf.co.uk.” All writings and photographs by Alan Lomax are copyright © 2003 by Alan Lomax estate. The material on “Sources and Permissions” on pp. 350–51 constitutes a continuation of this copyright page. All of the writings by Alan Lomax in this book are reprinted as they originally appeared, without emendation, except for small changes to regularize spelling. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilized in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Lomax, Alan, 1915–2002 [Selections] Alan Lomax : selected writings, 1934–1997 /edited by Ronald D.Cohen; with introductory essays by Gage Averill, Matthew Barton, Ronald D.Cohen, Ed Kahn, and Andrew Kaye. -

Enjoy the Magic of Walt Disney World All Year Long with Celebrations Magazine! Receive 6 Issues for $29.99* (Save More Than 15% Off the Cover Price!) *U.S

Enjoy the magic of Walt Disney World all year long with Celebrations magazine! Receive 6 issues for $29.99* (save more than 15% off the cover price!) *U.S. residents only. To order outside the United States, please visit www.celebrationspress.com. To subscribe to Celebrations magazine, clip or copy the coupon below. Send check or money order for $29.99 to: YES! Celebrations Press Please send me 6 issues of PO Box 584 Celebrations magazine Uwchland, PA 19480 Name Confirmation email address Address City State Zip You can also subscribe online at www.celebrationspress.com. On the Cover: “Splash!”, photo by Tim Devine Issue 24 Taking the Plunge on 42 Contents Splash Mountain Letters ..........................................................................................6 Calendar of Events ............................................................ 8 Disney News & Updates................................................10 MOUSE VIEWS ......................................................... 15 Guide to the Magic O Canada by Tim Foster............................................................................16 50 Explorer Emporium by Lou Mongello .....................................................................18 Hidden Mickeys by Steve Barrett .....................................................................20 Photography Tips & Tricks by Tim Devine .........................................................................22 Music in the Parks Pin Trading & Collecting by John Rick .............................................................................24 -

Monthly Program Synopsis: Disney Women Animators and the History of Cartooning February 26, 2019, MH Library

Monthly Program Synopsis: Disney Women Animators and the History of Cartooning February 26, 2019, MH Library Suman Ganapathy VP Programs, Yvonne Randolph introduced museum educator from the Walt Disney Museum, Danielle Thibodeau, in her signature vivacious style. It was followed by a fascinating and educational presentation by Thibodeau about women animators and their role in the history of cartooning as presented in the Disney Family Museum located in the Presidio, San Francisco. The talk began with a short history of the museum. The museum, which opened in 2009, was created by one of Walt Disney’s daughters, Diane Disney Miller. After discovering shoeboxes full of Walt Disney’s Oscar awards at the Presidio, Miller started a project to create a book about her father, but ended up with the museum instead. Disney’s entire life is presented in the museum’s interactive galleries, including his 248 awards, early drawings, animation, movies, music etc. His life was inspirational. Disney believed that failure helped an individual grow, and Thibodeau said that Disney always recounted examples from his own life where he never let initial failures stop him from reaching his goals. The history of cartooning is mainly the history of Walt Dissey productions. What was achieved in his studios was groundbreaking and new, and it took many hundreds of people to contribute to its success. The Nine Old Men: Walt Disney’s core group of animators were all white males, and worked on the iconic Disney movies, and received more than their share of encomium and accolades. The education team of the Walt Disney museum decided to showcase the many brilliant and under-appreciated women who worked at the Disney studios for the K-12 students instead. -

A Tribute to Walt Disney Productions Sunday, April 9, 1978

A Tribute to Walt Disney Productions Sunday, April 9, 1978 Delta Kappa ·Alpha's 39th. Annual Awards Banquet Delta Kappa Alpha National Honorary Cinema Fraternity Division of Ci111ma UNIVERSITY oF SouTHERN C ALIFORNIA ScHOOL OF P ERFORMI IIC AttTS U IIIVIRSITY PARK March 31, 1978 Los A IICELES, CALIFORNIA 90007 DKA Honorarits JuUe Andrtrr• Frtd. AJCaire Greetings: Lucill< Ball '..ucieo Ba1latd Anne Bu ur Ricbard Bnd1 On behalf of the Alpha Chapter of Delta Kappa Alpha, ~ittk~a~ , . the National Honorary Cinema Fraternity, I wish to Scaoley Conn extend my warmest welcome to you on the occasion ?x;~~~:u of our thirty-ninth Annual Awards Banqu7t. Delmer Dava rr::!eb~c o AllanDwon The fraternity was established in 1937 and is Blok< EdwordJ Rudf Fchr dedicated to the furthering of the film arts and to Sylvta FiDe )Obo Flory the promotion of better relations between the Gl<nn Ford Gene Fowler academic and practicing members of the industry, Marjorie Fowler both theatrical and non-theatrical. Our Greek ~~u~ ·r~:J•• Lee Garmc:t letters symbolize the Dramatic, Kinematic and Gl'ftr Ganoo John Gr¥cD Aesthetic aspects of film. Coond Hall Henry Hathawar Howard Hawks EdirhHnd Of our yearly activities, the Banquet is one of All red H irchcodt Wilton Holm the most gratifying. It gives us the opportunity Ross Hu nter John Hu•oo to recognize the truly talented people in the in Norman JcwiiOD "Chuck" {,OD .. dustry, people who direct its future. Crtnt K<l7 Stanley Kramer Lf~rv~!, This year we feel that the honorees are most ~lltmr Roubtn Mamoulian worthy of such distinction £or their tremendous WaherMaubau Sc:eYc McQueen contribution to the art of animation. -

The Life & Legacy of Walt Disney

The Life & Legacy of Walt Disney Panel Discussion Neal Gabler, Moderator Annenberg School for Communication University of Southern California November 15, 2006 1 The Norman Lear Center Neal Gabler: The Life & Legacy of Walt Disney The Norman Lear Center Neal Gabler The Norman Lear Center is a Neal Gabler, Senior Fellow at the multidisciplinary research and USC Annenberg Norman Lear Cen- public policy center exploring ter, is an author, cultural historian, implications of the convergence and film critic. His first book, An of entertainment, commerce, Empire of Their Own: How the Jews and society. From its base in the Invented Hollywood, won the Los USC Annenberg School for Angeles Times Book Prize and the Communication, the Lear Center Theatre Library Association Award. builds bridges between eleven His second book, Winchell: Gossip, schools whose faculty study Power and the Culture of Celebrity, aspects of entertainment, media, was named non-fiction book of the and culture. Beyond campus, it year by Time magazine. Newsweek calls his most recent book, Walt Disney: bridges the gap between the The Triumph of American Imagination, “the definitive Disney bio.” entertainment industry and academia, and between them He appears regularly on the media review program Fox News Watch, and and the public. For more writes often for the New York Times and the Los Angeles Times. Gabler information, please visit has contributed to numerous other publications including Esquire, Salon, www.learcenter.org. New York Magazine, Vogue, American Heritage, The New York Republic, Us and Playboy. He has appeared on many television programs including The Today Show, The CBS Morning News, The News Hour, Entertainment To- night, Charlie Rose, and Good Morning America. -

March 2018 the Unitarian Universalist Fellowship of Fredericksburg News & Notes UUFF Women’S Book Group: Join Us at 6:00 P.M

March 2018 The Unitarian Universalist Fellowship of Fredericksburg News & Notes UUFF Women’s Book Group: Join us at 6:00 p.m. on Sunday, March 11 at Shirley Santulli’s home to discuss The Storied Life of A.J. Fikry, by Gabrielle Zevin. Described by NPR as a “love letter to the joys of reading,” Zevin’s Saturday, March 3 at 5 pm novel focuses on unlikely romantic hero A.J. Fikry, a bookstore owner and Bring the family and sing along to this beloved movie musical! widower. If you need a copy of the book or directions, contact Susan Park Potluck & Costume Contest or Diane Elstein. Bring a dish to share. Dress as a favorite character. Monday Music Gathering: For music $5 per person, $20 per family makers of all ages, levels, and instru- Contact Nancy Krause for advance reservations (advisable) ments. In March, we meet on the 12th or pay at the door if you didn’t purchase this and 26th, and then every other Monday at our 2017 Auction. evening in the high school classroom from 6:30-8:30 p.m. For more informa- tion, contact Lee Criscuolo. Women’s Group: Third Monday of the month at 7:00 p.m. On March 19, we’ll Sponsored by Music Committee with RE & Friendship meet at Aladin in the Greenbrier Shop- ping Center (2052 Plank Rd). We’ll be in the dining room (door on the right), TH not the hookah bar. Newcomers are especially encouraged to join us. Check ANNUAL at YOUR SERVICE us out on Facebook: https://www.face- book.com/groups/303460327502. -

March 4 April 13 April 24

SERVING THE ACTIVE MIND SPRING/SUMMER 2019 March 4 Registration begins April 13 Picnic Day with OLLI We Want You! Details on page 1 April 24 Bodega Bay Marine Lab Tour Tour research facilities and walk the trails Details on page 12 BECOME A MEMBER OF OSHER LIFELONG LEARNING INSTITUTE (OLLI) Courses and Events for Seniors OLLI Annual Membership Fee Class Locations (You must be a current OLLI member to enroll Davis Arts Center in OLLI courses or events.) 1919 F St., Davis Rooms: Boardroom or Studio F FULL YEAR Sept. 1, 2018 – Aug. 31, 2019 $50 Galileo Court (map on page 19) 2/3 YEAR Jan. 1, 2019 – Aug. 31, 2019 $40 1909 Galileo Ct., Suite B, Davis 1/3 YEAR April 1, 2019 – Aug. 31, 2019 $20 Located behind Kaiser Medical Offices in south If you are not sure you have a current membership, Davis off of Drew Ave. on Galileo Ct. (Same door as please call Student Services at (530) 757-8777. UC Davis Forensic Science, middle of the building.) Unitarian Universalist Church (map on page 19) 27074 Patwin Rd. Located in west Davis off of Russell Blvd. To Enroll Davis Musical Theatre Company (map on page 20) By Phone (530) 757-8777 607 Pena Dr., Davis In Person UC Davis Continuing and Professional Education Exclusive OLLI Membership Offer Student Services Office for Members of UC Davis Retirees’ 1333 Research Park Dr. Davis, CA 95618 Association (UCDRA) and UC DAVIS 8:30 a.m.-4:30 p.m. Monday-Friday Emeriti Association (UCDEA) Online cpe.ucdavis.edu/olli To help build a more sustainable OLLI and engage Enrolling online requires an account. -

Kent Bingham's History with Disney

KENT BINGHAM’S HISTORY WITH DISNEY This history was started when a friend asked me a question regarding “An Abandoned Disney Park”: THE QUESTION From: pinpointnews [mailto:[email protected]] Sent: Tuesday, March 22, 2016 3:07 AM To: Kent Bingham Subject: Photographer Infiltrates Abandoned Disney Park - Coast to Coast AM http://www.coasttocoastam.com/pages/photographer-infiltrates-abandoned-disney-park Could the abandoned island become an OASIS PREVIEW CENTER??? NOTE I and several of my friends have wanted to complete the EPCOT vision as a city where people could live and work. We have been looking for opportunities to do this for the last 35 years, ever since we completed EPCOT at Disney World on October 1, 1983. We intend to do this in a small farming community patterned after the life that Walt and Roy experienced in Marceline, Missouri, where they lived from 1906-1910. They so loved their life in Marceline that it became the inspiration for Main Street in Disneyland. We will call our town an OASIS VILLAGE. It will become a showcase and a preview center for all of our OASIS TECHNOLOGIES. We are on the verge of doing this, but first we had to invent the OASIS MACHINE. You can learn all about it by looking at our website at www.oasis-system.com . There you will learn that the OM provides water and energy (at minimum cost) that will allow people to grow their own food. This machine is a real drought buster, and will be in demand all over the world. This will provide enough income for us to build our OVs in many locations. -

1C0sn24j7 347416.Pdf

Apr-May 2016 Disneyana Fan Club Disneyana Dispatch Newsletter From The President: By Linda Rolls BOARD OF DIRECTORS 2015-2017 PRESIDENT Spring has Sprung....and sum- are: 1) Increased nationally Linda Rolls mer will be here before we sponsored events in areas oth- [email protected] know it. We are gearing up for er than Southern California; VICE PRESIDENT OF FINANCE an amazing convention in July. 2) More support for chapters; Louis Boish Please be sure to check out 3) Better communication over- [email protected] the information in this news- all. Through a Strategic Plan- VICE PRESIDENT OF MEMBERSHIP letter regarding the seminars, ning process, we will use your Jeannie Lee [email protected] banquets, and registration. input to develop a detailed Reserve early to get the best plan for the future. We want VICE PRESIDENT OF CHAPTERS Gary Des Combes pricing. you to know that your voices [email protected] are being heard. You may peri- VICE PRESIDENT OF MEDIA RELATIONS & As many have already heard, odically see follow up surveys COMMUNICATIONS D23 has announced their next in the future to help us clar- Dr. Andi Stein Expo for 2017 to take place at ify some of the information we [email protected] the same time we would ordi- received. and your direct par- SECRETARY narily hold our convention. ticipation will be a critical Ted Bradpiece Clearly, we won't be planning piece of the improvement pro- [email protected] anything that would be in com- cess. Stay tuned! EDITOR-IN-CHIEF petition with the Expo, but we Bob Welbaum [email protected] are considering our options.