An Interview with Robert Aumann ∗

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

TECHNOLOGY and GROWTH: an OVERVIEW Jeffrey C

Y Proceedings GY Conference Series No. 40 Jeffrey C. Fuhrer Jane Sneddon Little Editors CONTENTS TECHNOLOGY AND GROWTH: AN OVERVIEW Jeffrey C. Fuhrer and Jane Sneddon Little KEYNOTE ADDRESS: THE NETWORKED BANK 33 Robert M. Howe TECHNOLOGY IN GROWTH THEORY Dale W. Jorgenson Discussion 78 Susanto Basu Gene M. Grossman UNCERTAINTY AND TECHNOLOGICAL CHANGE 91 Nathan Rosenberg Discussion 111 Joel Mokyr Luc L.G. Soete CROSS-COUNTRY VARIATIONS IN NATIONAL ECONOMIC GROWTH RATES," THE ROLE OF aTECHNOLOGYtr 127 J. Bradford De Long~ Discussion 151 Jeffrey A. Frankel Adam B. Jaffe ADDRESS: JOB ~NSECURITY AND TECHNOLOGY173 Alan Greenspan MICROECONOMIC POLICY AND TECHNOLOGICAL CHANGE 183 Edwin Mansfield Discnssion 201 Samuel S. Kortum Joshua Lerner TECHNOLOGY DIFFUSION IN U.S. MANUFACTURING: THE GEOGRAPHIC DIMENSION 215 Jane Sneddon Little and Robert K. Triest Discussion 260 John C. Haltiwanger George N. Hatsopoulos PANEL DISCUSSION 269 Trends in Productivity Growth 269 Martin Neil Baily Inherent Conflict in International Trade 279 Ralph E. Gomory Implications of Growth Theory for Macro-Policy: What Have We Learned? 286 Abel M. Mateus The Role of Macroeconomic Policy 298 Robert M. Solow About the Authors Conference Participants 309 TECHNOLOGY AND GROWTH: AN OVERVIEW Jeffrey C. Fuhrer and Jane Sneddon Little* During the 1990s, the Federal Reserve has pursued its twin goals of price stability and steady employment growth with considerable success. But despite--or perhaps because of--this success, concerns about the pace of economic and productivity growth have attracted renewed attention. Many observers ruefully note that the average pace of GDP growth has remained below rates achieved in the 1960s and that a period of rapid investment in computers and other capital equipment has had disappointingly little impact on the productivity numbers. -

Matchings and Games on Networks

Matchings and games on networks by Linda Farczadi A thesis presented to the University of Waterloo in fulfilment of the thesis requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Combinatorics and Optimization Waterloo, Ontario, Canada, 2015 c Linda Farczadi 2015 Author's Declaration I hereby declare that I am the sole author of this thesis. This is a true copy of the thesis, including any required final revisions, as accepted by my examiners. I understand that my thesis may be made electronically available to the public. ii Abstract We investigate computational aspects of popular solution concepts for different models of network games. In chapter 3 we study balanced solutions for network bargaining games with general capacities, where agents can participate in a fixed but arbitrary number of contracts. We fully characterize the existence of balanced solutions and provide the first polynomial time algorithm for their computation. Our methods use a new idea of reducing an instance with general capacities to an instance with unit capacities defined on an auxiliary graph. This chapter is an extended version of the conference paper [32]. In chapter 4 we propose a generalization of the classical stable marriage problem. In our model the preferences on one side of the partition are given in terms of arbitrary bi- nary relations, that need not be transitive nor acyclic. This generalization is practically well-motivated, and as we show, encompasses the well studied hard variant of stable mar- riage where preferences are allowed to have ties and to be incomplete. Our main result shows that deciding the existence of a stable matching in our model is NP-complete. -

John Von Neumann Between Physics and Economics: a Methodological Note

Review of Economic Analysis 5 (2013) 177–189 1973-3909/2013177 John von Neumann between Physics and Economics: A methodological note LUCA LAMBERTINI∗y University of Bologna A methodological discussion is proposed, aiming at illustrating an analogy between game theory in particular (and mathematical economics in general) and quantum mechanics. This analogy relies on the equivalence of the two fundamental operators employed in the two fields, namely, the expected value in economics and the density matrix in quantum physics. I conjecture that this coincidence can be traced back to the contributions of von Neumann in both disciplines. Keywords: expected value, density matrix, uncertainty, quantum games JEL Classifications: B25, B41, C70 1 Introduction Over the last twenty years, a growing amount of attention has been devoted to the history of game theory. Among other reasons, this interest can largely be justified on the basis of the Nobel prize to John Nash, John Harsanyi and Reinhard Selten in 1994, to Robert Aumann and Thomas Schelling in 2005 and to Leonid Hurwicz, Eric Maskin and Roger Myerson in 2007 (for mechanism design).1 However, the literature dealing with the history of game theory mainly adopts an inner per- spective, i.e., an angle that allows us to reconstruct the developments of this sub-discipline under the general headings of economics. My aim is different, to the extent that I intend to pro- pose an interpretation of the formal relationships between game theory (and economics) and the hard sciences. Strictly speaking, this view is not new, as the idea that von Neumann’s interest in mathematics, logic and quantum mechanics is critical to our understanding of the genesis of ∗I would like to thank Jurek Konieczny (Editor), an anonymous referee, Corrado Benassi, Ennio Cavaz- zuti, George Leitmann, Massimo Marinacci, Stephen Martin, Manuela Mosca and Arsen Palestini for insightful comments and discussion. -

![Kenneth J. Arrow [Ideological Profiles of the Economics Laureates] Daniel B](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/0234/kenneth-j-arrow-ideological-profiles-of-the-economics-laureates-daniel-b-620234.webp)

Kenneth J. Arrow [Ideological Profiles of the Economics Laureates] Daniel B

Kenneth J. Arrow [Ideological Profiles of the Economics Laureates] Daniel B. Klein Econ Journal Watch 10(3), September 2013: 268-281 Abstract Kenneth J. Arrow is among the 71 individuals who were awarded the Sveriges Riksbank Prize in Economic Sciences in Memory of Alfred Nobel between 1969 and 2012. This ideological profile is part of the project called “The Ideological Migration of the Economics Laureates,” which fills the September 2013 issue of Econ Journal Watch. Keywords Classical liberalism, economists, Nobel Prize in economics, ideology, ideological migration, intellectual biography. JEL classification A11, A13, B2, B3 Link to this document http://econjwatch.org/file_download/715/ArrowIPEL.pdf ECON JOURNAL WATCH Kenneth J. Arrow by Daniel B. Klein Ross Starr begins his article on Kenneth Arrow (1921–) in The New Palgrave Dictionary of Economics by saying that he “is a legendary figure, with an enormous range of contributions to 20th-century economics…. His impact is suggested by the number of major ideas that bear his name: Arrow’s Theorem, the Arrow- Debreu model, the Arrow-Pratt index of risk aversion, and Arrow securities” (Starr 2008). Besides the four areas alluded to in the quotation from Starr, Arrow has been a leader in the economics of information. In 1972, at the age of 51 (still the youngest ever), Arrow shared the Nobel Prize in economics with John Hicks for their contributions to general economic equilibrium theory and welfare theory. But if the Nobel economics prize were given for specific accomplishments, and an individual could win repeatedly, Arrow would surely have several. It has been shown that Arrow is the economics laureate who has been most cited within the Nobel award lectures of the economics laureates (Skarbek 2009). -

The Death of Welfare Economics: History of a Controversy

A Service of Leibniz-Informationszentrum econstor Wirtschaft Leibniz Information Centre Make Your Publications Visible. zbw for Economics Igersheim, Herrade Working Paper The death of welfare economics: History of a controversy CHOPE Working Paper, No. 2017-03 Provided in Cooperation with: Center for the History of Political Economy at Duke University Suggested Citation: Igersheim, Herrade (2017) : The death of welfare economics: History of a controversy, CHOPE Working Paper, No. 2017-03, Duke University, Center for the History of Political Economy (CHOPE), Durham, NC This Version is available at: http://hdl.handle.net/10419/155466 Standard-Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Die Dokumente auf EconStor dürfen zu eigenen wissenschaftlichen Documents in EconStor may be saved and copied for your Zwecken und zum Privatgebrauch gespeichert und kopiert werden. personal and scholarly purposes. Sie dürfen die Dokumente nicht für öffentliche oder kommerzielle You are not to copy documents for public or commercial Zwecke vervielfältigen, öffentlich ausstellen, öffentlich zugänglich purposes, to exhibit the documents publicly, to make them machen, vertreiben oder anderweitig nutzen. publicly available on the internet, or to distribute or otherwise use the documents in public. Sofern die Verfasser die Dokumente unter Open-Content-Lizenzen (insbesondere CC-Lizenzen) zur Verfügung gestellt haben sollten, If the documents have been made available under an Open gelten abweichend von diesen Nutzungsbedingungen die in der dort Content Licence (especially Creative Commons Licences), you genannten Lizenz gewährten Nutzungsrechte. may exercise further usage rights as specified in the indicated licence. www.econstor.eu The death of welfare economics: History of a controversy by Herrade Igersheim CHOPE Working Paper No. 2017-03 January 2017 Electronic copy available at: https://ssrn.com/abstract=2901574 The death of welfare economics: history of a controversy Herrade Igersheim December 15, 2016 Abstract. -

Chapter 11 Eric S. Maskin

Chapter 11 Eric S. Maskin BIOGRAPHY ERIC S. MASKIN, USA ECONOMICS, 2007 When seeking a solution to a problem it is possible, particularly in a non-specific field such as economics, to come up with several plausible answers. One may stand out as the most likely candi- date, but it may also be worth pursuing other options – indeed, this is a central strand of John Nash’s game theory, romantically illustrated in the film A Beautiful Mind. R. M. Solow et al. (eds.), Economics for the Curious © Foundation Lindau Nobelprizewinners Meeting at Lake Constance 2014 160 ERIC S. MASKIN Eric Maskin, along with Leonid Hurwicz and Roger Myerson, was awarded the 2007 Nobel Prize in Economics for their related work on mechanism design theory, a mathematical system for analyzing the best way to align incentives between parties. This not only helps when designing contracts between individuals but also when planning effective government regulation. Maskin’s contribution was the development of implementa- tion theory for achieving particular social or economic goals by encouraging conditions under which all equilibria are opti- mal. Maskin came up with his theory early in his career, after his PhD advisor, Nobel Laureate Kenneth Arrow, introduced him to Leonid Hurwicz. Maskin explains: ‘I got caught up in a problem inspired by the work of Leo Hurwicz: under what cir- cumstance is it possible to design a mechanism (that is, a pro- cedure or game) that implements a given social goal, or social choice rule? I finally realized that monotonicity (now sometimes called ‘Maskin monotonicity’) was the key: if a social choice rule doesn't satisfy monotonicity, then it is not implementable; and if it does satisfy this property it is implementable provided no veto power, a weak requirement, also holds. -

Koopmans in the Soviet Union

Koopmans in the Soviet Union A travel report of the summer of 1965 Till Düppe1 December 2013 Abstract: Travelling is one of the oldest forms of knowledge production combining both discovery and contemplation. Tjalling C. Koopmans, research director of the Cowles Foundation of Research in Economics, the leading U.S. center for mathematical economics, was the first U.S. economist after World War II who, in the summer of 1965, travelled to the Soviet Union for an official visit of the Central Economics and Mathematics Institute of the Soviet Academy of Sciences. Koopmans left with the hope to learn from the experiences of Soviet economists in applying linear programming to economic planning. Would his own theories, as discovered independently by Leonid V. Kantorovich, help increasing allocative efficiency in a socialist economy? Koopmans even might have envisioned a research community across the iron curtain. Yet he came home with the discovery that learning about Soviet mathematical economists might be more interesting than learning from them. On top of that, he found the Soviet scene trapped in the same deplorable situation he knew all too well from home: that mathematicians are the better economists. Key-Words: mathematical economics, linear programming, Soviet economic planning, Cold War, Central Economics and Mathematics Institute, Tjalling C. Koopmans, Leonid V. Kantorovich. Word-Count: 11.000 1 Assistant Professor, Department of economics, Université du Québec à Montréal, Pavillon des Sciences de la gestion, 315, Rue Sainte-Catherine Est, Montréal (Québec), H2X 3X2, Canada, e-mail: [email protected]. A former version has been presented at the conference “Social and human sciences on both sides of the ‘iron curtain’”, October 17-19, 2013, in Moscow. -

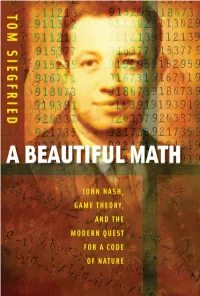

A Beautiful Math : John Nash, Game Theory, and the Modern Quest for a Code of Nature / Tom Siegfried

A BEAUTIFULA BEAUTIFUL MATH MATH JOHN NASH, GAME THEORY, AND THE MODERN QUEST FOR A CODE OF NATURE TOM SIEGFRIED JOSEPH HENRY PRESS Washington, D.C. Joseph Henry Press • 500 Fifth Street, NW • Washington, DC 20001 The Joseph Henry Press, an imprint of the National Academies Press, was created with the goal of making books on science, technology, and health more widely available to professionals and the public. Joseph Henry was one of the founders of the National Academy of Sciences and a leader in early Ameri- can science. Any opinions, findings, conclusions, or recommendations expressed in this volume are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Academy of Sciences or its affiliated institutions. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Siegfried, Tom, 1950- A beautiful math : John Nash, game theory, and the modern quest for a code of nature / Tom Siegfried. — 1st ed. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 0-309-10192-1 (hardback) — ISBN 0-309-65928-0 (pdfs) 1. Game theory. I. Title. QA269.S574 2006 519.3—dc22 2006012394 Copyright 2006 by Tom Siegfried. All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America. Preface Shortly after 9/11, a Russian scientist named Dmitri Gusev pro- posed an explanation for the origin of the name Al Qaeda. He suggested that the terrorist organization took its name from Isaac Asimov’s famous 1950s science fiction novels known as the Foun- dation Trilogy. After all, he reasoned, the Arabic word “qaeda” means something like “base” or “foundation.” And the first novel in Asimov’s trilogy, Foundation, apparently was titled “al-Qaida” in an Arabic translation. -

2Majors and Minors.Qxd.KA

APPLIED MATHEMATICS AND STATISTICS Spring 2007: updates since Fall 2006 are in red Applied Mathematics and Statistics (AMS) Major and Minor in Applied Mathematics and Statistics Department of Applied Mathematics and Statistics, College of Engineering and Applied Sciences CHAIRPERSON: James Glimm UNDERGRADUATE PROGRAM DIRECTOR: Alan C. Tucker UNDERGRADUATE SECRETARY: Elizabeth Ahmad OFFICE: P-139B Math Tower PHONE: (631) 632-8370 E-MAIL: [email protected] WEB ADDRESS: http://naples.cc.sunysb.edu/CEAS/amsweb.nsf Students majoring in Applied Mathematics and Statistics often double major in one of the following: Computer Science (CSE), Economics (ECO), Information Systems (ISE) Faculty Bradley Plohr, Adjunct Professor, Ph.D., he undergraduate program in Princeton University: Conservation laws; com- Hongshik Ahn, Associate Professor, Ph.D., Applied Mathematics and Statistics putational fluid dynamics. University of Wisconsin: Biostatistics; survival Taims to give mathematically ori- analysis. John Reinitz, Professor, Ph.D., Yale University: ented students a liberal education in quan- Mathematical biology. Esther Arkin, Professor, Ph.D., Stanford titative problem solving. The courses in University: Computational geometry; combina- Robert Rizzo, Assistant Professor, Ph.D., Yale this program survey a wide variety of torial optimization. University: Bioinformatics; drug design. mathematical theories and techniques Edward J. Beltrami, Professor Emeritus, Ph.D., David Sharp, Adjunct Professor, Ph.D., that are currently used by analysts and Adelphi University: Optimization; stochastic California Institute of Technology: Mathematical researchers in government, industry, and models. physics. science. Many of the applied mathematics Yung Ming Chen, Professor Emeritus, Ph.D., Ram P. Srivastav, Professor, D.Sc., University of courses give students the opportunity to New York University: Partial differential equa- Glasgow; Ph.D., University of Lucknow: Integral develop problem-solving techniques using equations; numerical solutions. -

Games of Threats

Accepted Manuscript Games of threats Elon Kohlberg, Abraham Neyman PII: S0899-8256(17)30190-2 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geb.2017.10.018 Reference: YGAME 2771 To appear in: Games and Economic Behavior Received date: 30 August 2017 Please cite this article in press as: Kohlberg, E., Neyman, A. Games of threats. Games Econ. Behav. (2017), https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geb.2017.10.018 This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain. GAMES OF THREATS ELON KOHLBERG∗ AND ABRAHAM NEYMAN+ Abstract. Agameofthreatsonafinitesetofplayers,N, is a function d that assigns a real number to any coalition, S ⊆ N, such that d(S)=−d(N \S). A game of threats is not necessarily a coalitional game as it may fail to satisfy the condition d(∅)=0.We show that analogs of the classic Shapley axioms for coalitional games determine a unique value for games of threats. This value assigns to each player an average of d(S)acrossall the coalitions that include the player. Games of threats arise naturally in value theory for strategic games, and may have applications in other branches of game theory. 1. Introduction The Shapley value is the most widely studied solution concept of cooperative game theory. -

DEPARTMENT of ECONOMICS NEWSLETTER Issue #1

DEPARTMENT OF ECONOMICS NEWSLETTER Issue #1 DEPARTMENT OF ECONOMICS SEPTEMBER 2017 STONY BROOK UNIVERSITY IN THIS ISSUE Message from the Chair by Juan Carlos Conesa Greetings from the Department of Regarding news for the coming Economics in the College of Arts and academic year, we are very excited to Sciences at Stony Brook University! announce that David Wiczer, currently Since the beginning of the spring working for the Research Department of semester, we’ve celebrated several the Federal Reserve Bank of St Louis, 2017 Commencement Ceremony accomplishments of both students and will be joining us next semester as an Juan Carlos Conesa, Vincent J. Cassidy (BA ‘81), Anand George (BA ‘02) and Hugo faculty alike. I’d also like to tell you of Assistant Professor. David is an what’s to come for next year. enthusiastic researcher working on the Benitez‐Silva intersection of Macroeconomics and The beginning of 2017 has been a very Labor Economics, with a broad exciting time for our students. Six of our perspective combining theoretical, PhD students started looking for options computational and data analysis. We are to start exciting professional careers. really looking forward to David’s Arda Aktas specializes in Demographics, interaction with both students and and will be moving to a Post‐doctoral faculty alike. We are also happy to position at the World Population welcome Prof. Basak Horowitz, who will Program in the International Institute for join the Economics Department in Fall Applied Systems Analysis (IIASA), in 2017, as a new Lecturer. Basak’s Austria. Anju Bhandari specializes in research interests are microeconomic Macroeconomics, and has accepted a theory, economics of networks and New faculty, David Wiczer position as an Assistant Vice President matching theory, industrial organization with Citibank, NY. -

Games of Threats

Games of Threats The Harvard community has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters Citation Kohlberg, Elon, and Abraham Neyman. "Games of Threats." Games and Economic Behavior 108 (March 2018): 139–145. Citable link http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:39148383 Terms of Use This article was downloaded from Harvard University’s DASH repository, and is made available under the terms and conditions applicable to Open Access Policy Articles, as set forth at http:// nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:dash.current.terms-of- use#OAP GAMES OF THREATS ELON KOHLBERG∗ AND ABRAHAM NEYMAN+ Abstract. Agameofthreatsonafinitesetofplayers,N, is a function d that assigns a real number to any coalition, S ⊆ N, such that d(S)=−d(N \S). A game of threats is not necessarily a coalitional game as it may fail to satisfy the condition d(∅)=0.We show that analogs of the classic Shapley axioms for coalitional games determine a unique value for games of threats. This value assigns to each player an average of d(S)acrossall the coalitions that include the player. Games of threats arise naturally in value theory for strategic games, and may have applications in other branches of game theory. 1. Introduction The Shapley value is the most widely studied solution concept of cooperative game theory. It is defined on coalitional games, which are the standard objects of the theory. A coalitional game on a finite set of players, N, is a function v that assigns a real number to any subset (“coalition”), S ⊆ N, such that v(∅) = 0.