TECHNOLOGY and GROWTH: an OVERVIEW Jeffrey C

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Stephan Heblich Stephen J. Redding Daniel M. Sturm

THE MAKING OF THE MODERN METROPOLIS: EVIDENCE FROM LONDON∗ Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/qje/article/135/4/2059/5831735 by Princeton University user on 21 August 2020 STEPHAN HEBLICH STEPHEN J. REDDING DANIEL M. STURM Using newly constructed spatially disaggregated data for London from 1801 to 1921, we show that the invention of the steam railway led to the first large-scale separation of workplace and residence. We show that a class of quantitative urban models is remarkably successful in explaining this reorganization of economic ac- tivity. We structurally estimate one of the models in this class and find substantial agglomeration forces in both production and residence. In counterfactuals, we find that removing the whole railway network reduces the population and the value of land and buildings in London by up to 51.5% and 53.3% respectively, and decreases net commuting into the historical center of London by more than 300,000 workers. JEL Codes: O18, R12, R40 I. INTRODUCTION Modern metropolitan areas include vast concentrations of economic activity, with Greater London and New York City today ∗We are grateful to the University of Bristol, the London School of Economics, Princeton University, and the University of Toronto for research support. Heblich also acknowledges support from the Institute for New Economic Thinking (INET) Grant no. INO15-00025. We thank the editor, four anonymous referees, Victor Cou- ture, Jonathan Dingel, Ed Glaeser, Vernon Henderson, Petra Moser, Leah Platt Boustan, Will Strange, Claudia Steinwender, Matt Turner, Jerry White, Christian Wolmar, and conference and seminar participants at Berkeley, Canadian Institute for Advanced Research (CIFAR), Centre for Economic Policy Research (CEPR), Columbia, Dartmouth, EIEF Rome, European Economic Association, Fed Board, Geneva, German Economic Association, Harvard, IDC Herzliya, LSE, Marseille, MIT, National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER), Nottingham, Princeton, Singapore, St. -

Functional Forms for Tractable Economic Models and the Cost Structure of International Trade∗

Functional Forms for Tractable Economic Models and the Cost Structure of International Trade∗ Michal Fabingery E. Glen Weylz August 2018 Abstract We present functional forms allowing a broader range of analytic solutions to common economic equilibrium problems. These can increase the realism of pen-and-paper solutions or speed large-scale numerical solutions as computational subroutines. We use the latter approach to build a tractable heterogeneous firm model of international trade accommodating economies of scale in export and diseconomies of scale in production, providing a natural, unified solution to several puzzles concerning trade costs. We briefly highlight applications in a range of other fields. Our method of generating analytic solutions is a discrete approximation to a logarithmically modified Laplace transform of equilibrium conditions. arXiv:1611.02270v2 [q-fin.EC] 18 Aug 2018 ∗This paper replaces its previous working versions \Pass-Through and Demand Forms"/\A Tractable Approach to Pass-Through Patterns"/\The Average-Marginal Relationship and Tractable Equilibrium Forms". We are grateful to many colleagues and seminar participants for helpful comments. We appreciate the research assistance of Konstantin Egorov, Eric Guan, Franklin Liu, Eva Lyubich, Yali Miao, Daichi Ueda, Ryo Takahashi, Huan Wang, and Xichao Wang. This research was funded by the Kauffman Foundation, the Becker Friedman Institute for Research in Economics, the Japan Science and Technology Agency and the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science to which we are grateful. We are particularly indebted to Jeremy Bulow for detailed discussion and for inspiring this work and to James Heckman for advice on relevant theorems in duration analysis and nonparametric estimation. -

How the Human Capital Model Explains Why the Gender Wage Gap Narrowed

A Service of Leibniz-Informationszentrum econstor Wirtschaft Leibniz Information Centre Make Your Publications Visible. zbw for Economics Polachek, Solomon W. Working Paper How the Human Capital Model Explains Why the Gender Wage Gap Narrowed IZA Discussion Papers, No. 1102 Provided in Cooperation with: IZA – Institute of Labor Economics Suggested Citation: Polachek, Solomon W. (2004) : How the Human Capital Model Explains Why the Gender Wage Gap Narrowed, IZA Discussion Papers, No. 1102, Institute for the Study of Labor (IZA), Bonn This Version is available at: http://hdl.handle.net/10419/20337 Standard-Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Die Dokumente auf EconStor dürfen zu eigenen wissenschaftlichen Documents in EconStor may be saved and copied for your Zwecken und zum Privatgebrauch gespeichert und kopiert werden. personal and scholarly purposes. Sie dürfen die Dokumente nicht für öffentliche oder kommerzielle You are not to copy documents for public or commercial Zwecke vervielfältigen, öffentlich ausstellen, öffentlich zugänglich purposes, to exhibit the documents publicly, to make them machen, vertreiben oder anderweitig nutzen. publicly available on the internet, or to distribute or otherwise use the documents in public. Sofern die Verfasser die Dokumente unter Open-Content-Lizenzen (insbesondere CC-Lizenzen) zur Verfügung gestellt haben sollten, If the documents have been made available under an Open gelten abweichend von diesen Nutzungsbedingungen die in der dort Content Licence (especially Creative Commons Licences), you genannten Lizenz gewährten Nutzungsrechte. may exercise further usage rights as specified in the indicated licence. www.econstor.eu IZA DP No. 1102 How the Human Capital Model Explains Why the Gender Wage Gap Narrowed Solomon W. Polachek DISCUSSION PAPER SERIES DISCUSSION PAPER April 2004 Forschungsinstitut zur Zukunft der Arbeit Institute for the Study of Labor How the Human Capital Model Explains Why the Gender Wage Gap Narrowed Solomon W. -

Baldwin Chapter 6 the Value Structure of Technologies 8-18-20

Design Rules, Volume 2: How Technology Shapes Organizations Chapter 6 The Value Structure of Technologies, Part 1: Mapping Functional Relationships Carliss Y. Baldwin Working Paper 21-039 Design Rules, Volume 2: How Technology Shapes Organizations Chapter 6 The Value Structure of Technologies, Part 1: Mapping Functional Relationships Carliss Y. Baldwin Harvard Business School Working Paper 21-039 Copyright © 2020 by Carliss Y. Baldwin Working papers are in draft form. This working paper is distributed for purposes of comment and discussion only. It may not be reproduced without permission of the copyright holder. Copies of working papers are available from the author. Funding for this research was provided in part by Harvard Business School. © Carliss Y. Baldwin Comments welcome. Please do not circulate or quote. Design Rules, Volume 2: How Technology Shapes Organizations Chapter 6 The Value Structure of Technologies, Part 1: Mapping Functional Relationships By Carliss Y. Baldwin Note to Readers: This is a draft of Chapter 6 of Design Rules, Volume 2: How Technology Shapes Organizations. It builds on prior chapters, but I believe it is possible to read this chapter on a stand-alone basis. The chapter may be cited as: Baldwin, C. Y. (2020) “The Value Structure of Technologies, Part 1: Mapping Functional Relationships,” Harvard Business School Working Paper (Rev. September 2020). I would be most grateful for your comments on any aspect of this chapter! Thank you in advance, Carliss. Abstract Organizations are formed in a free economy because an individual or group perceives value in carrying out a technical recipe that is beyond the capacity of a single person. -

Notes and Sources for Evil Geniuses: the Unmaking of America: a Recent History

Notes and Sources for Evil Geniuses: The Unmaking of America: A Recent History Introduction xiv “If infectious greed is the virus” Kurt Andersen, “City of Schemes,” The New York Times, Oct. 6, 2002. xvi “run of pedal-to-the-medal hypercapitalism” Kurt Andersen, “American Roulette,” New York, December 22, 2006. xx “People of the same trade” Adam Smith, The Wealth of Nations, ed. Andrew Skinner, 1776 (London: Penguin, 1999) Book I, Chapter X. Chapter 1 4 “The discovery of America offered” Alexis de Tocqueville, Democracy In America, trans. Arthur Goldhammer (New York: Library of America, 2012), Book One, Introductory Chapter. 4 “A new science of politics” Tocqueville, Democracy In America, Book One, Introductory Chapter. 4 “The inhabitants of the United States” Tocqueville, Democracy In America, Book One, Chapter XVIII. 5 “there was virtually no economic growth” Robert J Gordon. “Is US economic growth over? Faltering innovation confronts the six headwinds.” Policy Insight No. 63. Centre for Economic Policy Research, September, 2012. --Thomas Piketty, “World Growth from the Antiquity (growth rate per period),” Quandl. 6 each citizen’s share of the economy Richard H. Steckel, “A History of the Standard of Living in the United States,” in EH.net (Economic History Association, 2020). --Andrew McAfee and Erik Brynjolfsson, The Second Machine Age: Work, Progress, and Prosperity in a Time of Brilliant Technologies (New York: W.W. Norton, 2016), p. 98. 6 “Constant revolutionizing of production” Friedrich Engels and Karl Marx, Manifesto of the Communist Party (Moscow: Progress Publishers, 1969), Chapter I. 7 from the early 1840s to 1860 Tomas Nonnenmacher, “History of the U.S. -

Presidential Documents

Weekly Compilation of Presidential Documents Monday, October 3, 1994 Volume 30ÐNumber 39 Pages 1835±1915 1 VerDate 14-MAY-98 10:32 May 27, 1998 Jkt 010199 PO 00001 Frm 00001 Fmt 1249 Sfmt 1249 C:\TERRI\P39SE4.000 INET03 Contents Addresses and Remarks Appointments and Nominations See also Bill Signings; Meetings With Foreign Environmental Protection Agency, Deputy Leaders AdministratorÐ1869 Chicago, IL, Democratic Senatorial Campaign National Cancer Advisory Board, membersÐ Committee dinnerÐ1836 1911 Congressional Hispanic Caucus receptionÐ U.S. District Court, judgeÐ1836 1877 Bill Signings New York City Bethel A.M.E. ChurchÐ1851 Departments of Veterans Affairs and Housing Democratic Congressional Campaign and Urban Development, and Independent Committee dinnerÐ1855 Agencies Appropriations Act, 1995, United Nations statementÐ1889 General AssemblyÐ1862 Riegle-Neal Interstate Banking and Branching Luncheon for heads of stateÐ1867 Efficiency Act of 1994, remarksÐ1896 Reception for heads of state and U.N. Communications to Congress delegationsÐ1867 Belarus-U.S. investment treaty, message Radio addressÐ1841 transmittingÐ1836 Receptions for Senate candidates Compact of Free Association With the Alan Wheat in Kansas City, MOÐ1847 Republic of Palau, letterÐ1874 Ann Wynia in Minneapolis, MNÐ1842 General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade, Edward M. Kennedy in McLean, VAÐ1902 messageÐ1876 Visit of Russian President Yeltsin Haiti, message transmitting noticeÐ1909 Business leadersÐ1888 Proliferation of chemical and biological ``In the Beginning'' exhibit at the Library of weapons, messageÐ1907 CongressÐ1880 Russian and American veterans of World Communications to Federal Agencies War IIÐ1872 China, memorandumÐ1911 State dinnerÐ1879 Guatemala, memorandumÐ1911 Welcoming ceremonyÐ1869 Haiti, memorandumÐ1910 (Contents Continued on inside of back cover.) WEEKLY COMPILATION OF regulations prescribed by the Administrative Committee of the Federal Register, approved by the President (37 FR 23607; 1 CFR Part 10). -

![Kenneth J. Arrow [Ideological Profiles of the Economics Laureates] Daniel B](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/0234/kenneth-j-arrow-ideological-profiles-of-the-economics-laureates-daniel-b-620234.webp)

Kenneth J. Arrow [Ideological Profiles of the Economics Laureates] Daniel B

Kenneth J. Arrow [Ideological Profiles of the Economics Laureates] Daniel B. Klein Econ Journal Watch 10(3), September 2013: 268-281 Abstract Kenneth J. Arrow is among the 71 individuals who were awarded the Sveriges Riksbank Prize in Economic Sciences in Memory of Alfred Nobel between 1969 and 2012. This ideological profile is part of the project called “The Ideological Migration of the Economics Laureates,” which fills the September 2013 issue of Econ Journal Watch. Keywords Classical liberalism, economists, Nobel Prize in economics, ideology, ideological migration, intellectual biography. JEL classification A11, A13, B2, B3 Link to this document http://econjwatch.org/file_download/715/ArrowIPEL.pdf ECON JOURNAL WATCH Kenneth J. Arrow by Daniel B. Klein Ross Starr begins his article on Kenneth Arrow (1921–) in The New Palgrave Dictionary of Economics by saying that he “is a legendary figure, with an enormous range of contributions to 20th-century economics…. His impact is suggested by the number of major ideas that bear his name: Arrow’s Theorem, the Arrow- Debreu model, the Arrow-Pratt index of risk aversion, and Arrow securities” (Starr 2008). Besides the four areas alluded to in the quotation from Starr, Arrow has been a leader in the economics of information. In 1972, at the age of 51 (still the youngest ever), Arrow shared the Nobel Prize in economics with John Hicks for their contributions to general economic equilibrium theory and welfare theory. But if the Nobel economics prize were given for specific accomplishments, and an individual could win repeatedly, Arrow would surely have several. It has been shown that Arrow is the economics laureate who has been most cited within the Nobel award lectures of the economics laureates (Skarbek 2009). -

The Death of Welfare Economics: History of a Controversy

A Service of Leibniz-Informationszentrum econstor Wirtschaft Leibniz Information Centre Make Your Publications Visible. zbw for Economics Igersheim, Herrade Working Paper The death of welfare economics: History of a controversy CHOPE Working Paper, No. 2017-03 Provided in Cooperation with: Center for the History of Political Economy at Duke University Suggested Citation: Igersheim, Herrade (2017) : The death of welfare economics: History of a controversy, CHOPE Working Paper, No. 2017-03, Duke University, Center for the History of Political Economy (CHOPE), Durham, NC This Version is available at: http://hdl.handle.net/10419/155466 Standard-Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Die Dokumente auf EconStor dürfen zu eigenen wissenschaftlichen Documents in EconStor may be saved and copied for your Zwecken und zum Privatgebrauch gespeichert und kopiert werden. personal and scholarly purposes. Sie dürfen die Dokumente nicht für öffentliche oder kommerzielle You are not to copy documents for public or commercial Zwecke vervielfältigen, öffentlich ausstellen, öffentlich zugänglich purposes, to exhibit the documents publicly, to make them machen, vertreiben oder anderweitig nutzen. publicly available on the internet, or to distribute or otherwise use the documents in public. Sofern die Verfasser die Dokumente unter Open-Content-Lizenzen (insbesondere CC-Lizenzen) zur Verfügung gestellt haben sollten, If the documents have been made available under an Open gelten abweichend von diesen Nutzungsbedingungen die in der dort Content Licence (especially Creative Commons Licences), you genannten Lizenz gewährten Nutzungsrechte. may exercise further usage rights as specified in the indicated licence. www.econstor.eu The death of welfare economics: History of a controversy by Herrade Igersheim CHOPE Working Paper No. 2017-03 January 2017 Electronic copy available at: https://ssrn.com/abstract=2901574 The death of welfare economics: history of a controversy Herrade Igersheim December 15, 2016 Abstract. -

Chapter 11 Eric S. Maskin

Chapter 11 Eric S. Maskin BIOGRAPHY ERIC S. MASKIN, USA ECONOMICS, 2007 When seeking a solution to a problem it is possible, particularly in a non-specific field such as economics, to come up with several plausible answers. One may stand out as the most likely candi- date, but it may also be worth pursuing other options – indeed, this is a central strand of John Nash’s game theory, romantically illustrated in the film A Beautiful Mind. R. M. Solow et al. (eds.), Economics for the Curious © Foundation Lindau Nobelprizewinners Meeting at Lake Constance 2014 160 ERIC S. MASKIN Eric Maskin, along with Leonid Hurwicz and Roger Myerson, was awarded the 2007 Nobel Prize in Economics for their related work on mechanism design theory, a mathematical system for analyzing the best way to align incentives between parties. This not only helps when designing contracts between individuals but also when planning effective government regulation. Maskin’s contribution was the development of implementa- tion theory for achieving particular social or economic goals by encouraging conditions under which all equilibria are opti- mal. Maskin came up with his theory early in his career, after his PhD advisor, Nobel Laureate Kenneth Arrow, introduced him to Leonid Hurwicz. Maskin explains: ‘I got caught up in a problem inspired by the work of Leo Hurwicz: under what cir- cumstance is it possible to design a mechanism (that is, a pro- cedure or game) that implements a given social goal, or social choice rule? I finally realized that monotonicity (now sometimes called ‘Maskin monotonicity’) was the key: if a social choice rule doesn't satisfy monotonicity, then it is not implementable; and if it does satisfy this property it is implementable provided no veto power, a weak requirement, also holds. -

Is Published Semi-Annually by the Journal on Telecommunications & High Technology Law, Campus Box 401, Boulder, CO 80309-040

JOURNAL ON TELECOMMUNICATIONS & HIGH TECHNOLOGY LAW is published semi-annually by the Journal on Telecommunications & High Technology Law, Campus Box 401, Boulder, CO 80309-0401 ISSN: 1543-8899 Copyright © 2009 by the Journal on Telecommunications & High Technology Law an association of students sponsored by the University of Colorado School of Law and the Silicon Flatirons Telecommunications Program. POSTMASTER: Please send address changes to JTHTL, Campus Box 401, Boulder, CO 80309-0401 Subscriptions Domestic volume subscriptions are available for $45.00. City of Boulder subscribers please add $3.74 sales tax. Boulder County subscribers outside the City of Boulder please add $2.14 sales tax. Metro Denver subscribers outside of Boulder County please add $1.85 sales tax. Colorado subscribers outside of Metro Denver please add $1.31 sales tax. International volume subscriptions are available for $50.00. Inquiries concerning ongoing subscriptions or obtaining an individual issue should be directed to the attention of JTHTL Managing Editor at [email protected] or by writing JTHTL Managing Editor, Campus Box 401, Boulder, CO 80309-0401. Back issues in complete sets, volumes, or single issues may be obtained from: William S. Hein & Co., Inc., 1285 Main Street, Buffalo, NY 14209. Back issues may also be found in electronic format for all your research needs on HeinOnline http://heinonline.org/. Manuscripts JTHTL invites the submission of unsolicited manuscripts. Please send softcopy manuscripts to the attention of JTHTL Articles Editors at [email protected] in Word or PDF formats or through ExpressO at http://law.bepress.com/expresso. Hardcopy submissions may be sent to JTHTL Articles Editors, Campus Box 401, Boulder, CO 80309-0401. -

Economic Principals \273 Blog Archive \273 a Normal Professor

Economic Principals » Blog Archive » A Normal Professor http://www.economicprincipals.com/issues/2008.06.01/320.html Home June 1, 2008 David Warsh, Proprietor About Archives previous | contents | next Books A Normal Professor Receive the Bulldog Edition Perhaps, now that Harvard’s Russia scandal is receding into the past, Andrei Shleifer, 47, will take it easy. He has a steady stream of students, presides over a growing literature in comparative economics, and has developed an interesting sideline in the economics of persuasion. His wife, Nancy Zimmerman , runs a hedge fund that has seen explosive growth, today managing more than $3 billion for institutional clients; together the pair, through their start-ups, may have Economic Blogosphere amassed net worth of $40 million or more. (A columnist for Economics Portfolio magazine’s website subsequently estimated that Roundtable the figure may be closer to $1 bullion.) Their children are Economists View growing, his energetic parents live nearby, he superintends a steady stream of visitors to his villa in the south of France, and he keeps a hand in with developments in Russia. Economic Journalists For example, when Anders Aslund , of Washington’s Peterson Allan Sloan institute for International Economics, was in Cambridge, Amity Shlaes Mass. last winter, to celebrate the publication of How Andrew Leonard Capitalism Was Built: The Transformation of Central and Binyamin Appelbaum Eastern Europe, Russia, and Central Asia and Russia’s Bruce Bartlett Capitalist Revolution: Why Market Reform Succeeded and Carl Bialik Democracy Failed , Shleifer, the author of A Normal Catherine Rampell Country: Russia After Communism , threw a party for him at Charles Duhigg his spacious home on unpaved Bracebridge Road in suburban Christopher Caldwell Newton. -

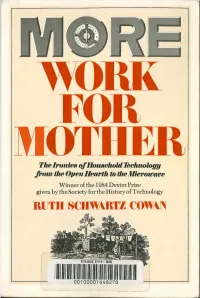

More Work for Mother

The It--onies ofHousehohl'JeehnowgiJ ft--om the Open Heat--th to the Miet--owave Winner of the 1984 Dexter Prize given by the Society for the History of Technology -RUTH SCHWARTZ COWAN ETHICS ETH·- BIB II II 111111 II II II llllllllllllll II 00100001648270 More Work for Mother MORE WORK FOR MOTHER The Ironies of Household Technology from the Open Hearth to the Microwave Ruth Schwartz Cowan • BasicBooks- A Division of HarperCollinsPub/ishen Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data Cowan, Ruth Schwartz, 1941- More work for mother. Bibliography: p. 220 Includes index. 1. Horne economics-United States-History. 2. Household appliances-United States-History. 3. Housewives-United States-History I. Title. II. Title: Household technology from the open hearth to the microwave. TX23.C64 1983 640'.973 83-70759 ISBN 0-465-04731-9 (cloth) ISBN 0-465-04732-7 (paper) Copyright © 1983 by Basic Books, Inc. Printed in the United States of America Designed by Vincent Torre 10 9 8 7 For Betty Schwartz and Louis E. Schwartz with love Contents PICTURE ESSAYS ix ACKNOWLEDGMENTS XI Chapter 1 An Introduction: Housework and Its Tools 3 Chapter 2 Housewifery: Household Work and Household Tools under Pre-Industrial Conditions 16 Housewifery and the Doctrine of Separate Spheres 18 Household Tools and Household Work 20 The Household Division of Labor 26 The Household and the Market Economy 31 Conclusion 3 7 Chapter 3 The Invention of Housework: The Early Stages of Industrialization 40 Milling Flour and Making Bread 46 The Evolution of the Stove 53 More Chores