Sustainability and the Irvine Company

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

CYPRESS VILLAGE SHOPPING CENTER Irvine, California

CYPRESS VILLAGE KEY TENANTS Albertsons AVERAGE DAILY SHOPPING CENTER Da Luau Hawaiian Gril TRAFFIC COUNTS 14001 - 14271 Jeffrey Rd. | Irvine, CA 92620 Kohl's 32,000 Mokkoji Shabu Shabu Bar Jeffrey Rd. at Trabuco Rd. 177,687 SF Gross Leasable Area Starbucks Coffee 11,000 • Within walking distance from the new community of Cypress Wells Fargo Bank Trabuco Rd. at Jeffrey Rd. Village, which will include 4,000+ units at completion with an 43,000 average value of $994,000 and two elementary schools Total • Draws customers from Orange County's fastest growing commerical and residential community, Irvine Spectrum® district, home to companies such as Verizon, KPMG, Mazda, DEMOGRAPHICS Taco Bell and others 3 MILE RADIUS • The nearby Orange County Great Park is under development and will have over 10,000 homes at completion with an 154,323 77,292 38 average value of $1 million POPULATION DAYTIME POPULATION AVERAGE AGE • Within two miles of Irvine Valley College (20,000+ students), $992,791 $151,158 Irvine High School (1,900+ students), Woodbridge High AVERAGE AVERAGE School (2,400+ students) and Beckman High School HOME VALUE HOUSEHOLD INCOME (3,000+ students) For leasing information, call Irvine Company at 949.720.2535 CYPRESS VILLAGE SHOPPING CENTER Irvine, California 50' 347'-3" 30'-4" 31'-4" 17'-4" 33'-4" 64'-1" 16' 184' 114' 76' 82'-1" 14201 14101 22'-2" 48'-3" 26' 28' 26' 24' 24' 22'-10" 3'-3" 150'-8" 89,168 SF 52,700 SF 14141 14171 14161 1,677 SF 14121 14131 14151 OLIVE OIL 3,219 SF 14191 VACANT 1,671 SF 1,697 SF 1,716 SF 1,974 SF TANG 190° -

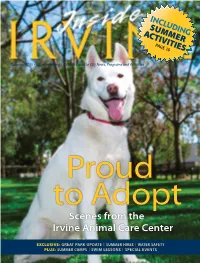

Entire Inside Irvine

Summer 2015 • cityofirvine.org • Official Guide to City News, Programs and Activities Proud to Adopt Scenes from the Irvine Animal Care Center EXCLUSIVE: GREAT PARK UPDATE | SUMMER HIKES | WATER SAFETY PLUS: SUMMER CAMPS | SWIM LESSONS | SPECIAL EVENTS Contents INSIDE THIS ISSUE Features 7 Irvine Animal Care Center Irvine City Council Join the circle of people who have been Mayor Steven S. Choi, Ph.D. Mayor Pro Tem Jeffrey Lalloway Proud to Adopt from the Irvine Animal Care Councilwoman Lynn Schott 7 Center. Learn about the stories behind the Councilmember Beth Krom Councilwoman/ Christina Shea animals and the animals just waiting for you— Chair, Great Park Board yes, you—to become an adoptive partner. City Manager Sean Joyce 12 Irvine’s Open Space Community Services Commission Chair Kevin Trussell The Irvine Ranch Conservancy has provided Vice Chair Michael Carroll five places to go this summer within the City’s Commissioner Scott Schultz Commissioner Melissa Fox 12 vast permanent open space. If the story doesn’t Commissioner Jim Shute convince you, the photography certainly will. Inside Irvine Editorial Managing Editor: Craig Reem Activity Guide Editor: Alana Kaleikini Activity Guide Coordinator: Dave Neustaedter Departments Contributors: Sawako Agravante, Jennifer Allanach, Shawnn Gallagher, Melissa Haley, Tom Macduff 2 Inside the City Manager’s Office Inside Irvine Art 3 Public Safety Update Art Director: Jonathan Price 13 Inside Irvine is published quarterly by the City of Irvine. Please address 4 News Briefs editorial correspondence to: Inside Irvine, c/o Public Information Office, 6 Great Park Report City of Irvine, PO Box 19575, Irvine, CA 92623-9575 or via email at [email protected]. -

Sports Facilities Guide Irvine, California

SPORTS FACILITIES GUIDE IRVINE, CALIFORNIA www.destinationirvine.com/sports Top 10 Reasons to Host a Sporting Event in Irvine Irvine offers a wide array of venues and facilities for virtually any sporting event. 1 First-class Facilities 5 Safety Some of the most beautiful sports facilities in Southern Recognized as “America’s Safest Big City” according to California, including the NEW 194-acre Orange County the FBI since 2005. Great Park Sports Complex. 2 Experience 6 Close to Perfect Weather Irvine averages 280+ sunny days a year! Temperatures Strong record of holding major events: range from highs between the mid 60s to mid 80s and lows from the 40s to 60s, with an annual high average 2018 NAIA Men's Soccer National Championship temperature of 72.7°F. 2017 USA Water Polo National Junior Olympics 7 Natural Beauty 2017 Softball Champions Cup 18-under Over 16,000 acres of parks, sports fields, and Junior Olympics Showcase dedicated open space offering miles of trails for 2016 USA Synchro West Zone Championships recreational fun, including 50 miles of off-road bike trails and 300 miles of on-road lanes. 2015 World Cup of Softball 8 Family Friendly 2014 USA Swimming Junior Nationals Family and kid-friendly attractions and activities, including Irvine Spectrum Center Giant Wheel and 1984 Olympic Games Swimming Great Park Balloon. 3 Accommodations for Every Budget 9 Center of Orange County Irvine boasts 21 hotels ranging from full-service to Close proximity to the area’s popular beaches and extended-stay with more than 4,700 sleeping rooms. famous attractions. -

Irvine Guide to Shop, Dine, Play and Explore Table of Contents

Irvine Guide to Shop, Dine, Play and Explore Table of Contents Arts/Culture, Attractions & Entertainment . 1 Golf . 6 Seasonal Events Calendar . 8 Special Events . 9 Parks & Recreation . 10 Retail Centers . 15 Restaurants . 33 Transportation . 45 Hospitals . 47 Disclaimer: The Irvine Guide to Shop, Dine, Play and Explore is provided as an informational resource and a community service to visitors. This Guide is not inclusive of all businesses in Irvine. The identification of companies, individuals and products is not intended and should not be treated as a recommendation, endorsement or approval by the City of Irvine. The City cannot and does not make any warranty or representation concerning the information contained in this Guide. While reasonable care has been taken to ensure the accuracy of the information in this Guide, the City shall not be held responsible for any errors or omissions. The information in this Guide may be changed in future publications. IRVINE GUIDE TO SHOP, DINE, PLAY AND EXPLORE • WWW.CITYOFIRVINE.ORG COSTA MESA FWY 55 REDHILL AVE. AL BARRANCA BR W IRVINE ALNUT MAIN TON VD. Y BL AN MICHELSON 19 CAMPUS PKWY A BL THUR ST VE A VD . VE . RD. MACAR . JAMBOREE RD 15 261 DR. Toll Rd A 24 VE. 14 6 9 16 1 HARVARD AVE. 4 BONIT UNIVERSITY CULVER DR. 2 IR 73 SAN DIEGO FWY VINE A 13 CANY YALE AVE. CENTER DRIVE POR 22 11 RD. ON 3 8 TOLA 23 A ANA FWY 7 DRIVE TRABUCO JEFFREY RD. Turtle PKWY Rock SANT 405 18 5 . RD. SAND CANYON AVE. CANYON SHADY 133 Toll Rd 241 17 LAGUNA CANYON RD 5 10 26 12 N 20 25 21 1. -

Shop Irvine SHOP IRVINE and COMMUNITY ACCESS GUIDE

Color indicates Irvine Chamber member www.irvinechamber.com • www.cityofirvine.org !PARTMENT3HOPPING-ADE¨ &REE&AST%ASY ;gZZ### ;Vhi### :Vhn### 8dbZ bZZi l^i] djg LZÉaa Xjhidb^oZ ndjg 6i djg GZciVa A^k^c\ =djh^c\ HeZX^Va^hih hZVgX]id[^cYndjgcZl 6eVgibZci>c[dgbVi^dc VcY hVkZ i^bZ [^cY^c\ VeVgibZciWnadXVi^dc! 8ZciZg! ndjÉaa [^cY ndjg ^YZVa ]dbZ### ^iÉh eg^XZ VcY VbZc^i^Zh# i]djhVcYh d[ dei^dch [gZZ# 8]ZX` dji djg gddb" dg hZVgX] dca^cZ ')$, bViZhZgk^XZidd# ViGZciVa"A^k^c\#Xdb### ^iÉhZVhn# &,+'*"7=VgkVgY!>gk^cZ!86.'+&) J$.--$)&.$.)+/ H[djWb#B_l_d]$Yec%?d\e9[dj[h 03873-IAC Info FFE-SIG.indd 1 9/25/09 2:29:13 PM 2010 Shop Irvine SHOP IRVINE AND COMMUNITY ACCESS GUIDE DEAR IRVINE SHOPPERS AND MEMBERS OF THE COMMUNITY: What do you get when you shop or dine at one of the nearly 50 shopping centers located in Irvine? You get a city recognized for five straight years as the safest city in America. You get a city that is known around the world for its quality educational facilities – a key ingredient for businesses looking for the best place to locate, grow and stay. You also get a master-planned city that is one of the most desirable locations in the country in which to live. When you SHOP IRVINE, you help everyone: One cent of sales tax for each dollar spent goes into the City’s general fund, which supports city services such as public safety, street and park maintenance, and community planning standards. -

For Lease Or Sale $500K+

IRVINE CENTER DRIVE $500K+ IRVINE SPECTRUM, CALIFORNIA PRICE REDUCTION FOR LEASE OR SALE VIRTUAL TOUR Represented by: TRAVIS HAINING ALTON BURGESS Lee & Associates - Newport Beach Voit Real Estate Services 949.724.4711 949.263.5397 [email protected] [email protected] DRE #: 01483191 DRE #: 01717094 IRVINE CENTER DRIVE IRVINE SPECTRUM, CALIFORNIA 8845 Irvine Center Drive is a freestanding 36,146 SF creative office/flex building located in the heart of Irvine Spectrum. A truly rare property that fits the definition of “Corporate Headquarters”. Ideally situated on 2.35 acres with 5.4(A) zoning that allows for a variety uses including architects, engineers, technology companies, R&D and software development. This unique asset has the image, zoning, location and ideal creative improvements desired by market demand. Previously the headquarters for Boost Mobile, 8845 Irvine Center Drive is now available for a new company to call it home. Sale Price: $375 PSF / $13,554,750 Lease Rate: TBD BUILDING FEATURES Building Size 36,146 SF Available Office SF 9,033-27,113 SF Warehouse SF TBD Parking Ratio 4.6:1,000 Power 2,000 Amps / 480 V VIRTUAL TOUR Zoning 5.4 (Design Professionals) Street Frontage Yes (Irvine Center Dr. & Hubble) Elevator Yes Sprinklers Yes Ground Level Loading Possible PROPERTY OVERVIEW Located at a signalized light on Irvine Center art lab facility in their space. Approximately 50% Drive, 8845 Irvine Center Drive is one of the best of the building (the full top floor) is currently locations in all of Spectrum. A truly freestanding leased to a national data security firm, and can creative office building with flexible rear loading be made available October 2021 or potentially doors and warehouse potential that provides for sooner. -

Retail Industry Profile, 2003

Retail Industry Profile for the Los Angeles Five-County Area ABC Store Card 12341234 56785678 90129012 VALID FROM GOOD THRU XX/XX/XX XX/XX/XX PAUL FISCHER September 2003 Edition Economic Information & Research Department Los Angeles County Economic Development Corp. 444 S. Flower St., 34th Floor, Los Angeles, CA 90071 Tel: 213-622-4300, 888-4-LAEDC-1, or 800-NEW-HELP Fax: 213-622-7100 (in LA County) http://www.laedc.org [email protected] Table of Contents Southern California Retail Industry Profile -- 2003.................................................................. 1 L.A.'s Retail Landscape ...................................................................................................... 1 New Names......................................................................................................................... 1 The Coming Storm.............................................................................................................. 2 Retailing By the Numbers................................................................................................... 3 Employment & Wages.................................................................................................. 3 Retail Sales Trends ....................................................................................................... 4 Retail Construction....................................................................................................... 5 A Sector-by-Sector Look ................................................................................................... -

Irvine Hotels & Sport Venues

CITY SPORT VENUES 1 Bill Barber 4 Civic Center Plaza 949-724-6714 Community Services 2 Cypress 255 Visions 949-724-6190 3 David Sills Lower Peters Canyon 3901 Farwell 949-724-6944 4 Harvard 14701 Harvard Ave. 949-724-6821 5 Heritage 14301 Walnut 949-724-6824 6 Hicks Canyon 3864 Viewpark Ave. 949-724-6827 Irvine Hotels 7 Las Lomas 10 Federation Way 949-724-6844 8 Mark Daily Athletic Field 308 West Yale Loop 949-724-6820 9 Northwood 4531 Bryan Ave. 949-724-6728 & Sport Venues 10 Oak Creek 15616 Valley Oak 11 Orange County Great Park 6950 Marine Way 949-724-6584 12 Quail Hill 35 Shady Canyon Dr. 949-724-6814 13 Woollett Aquatics Center 4601 Walnut Ave. 949-724-6717 14 Windrow 285 East Yale Loop 949-724-6828 241 15 Woodbury 130 Sanctuary 949-724-6840 F O 5 SANTA ANA FREEWAY 261 O T I L L 17 T WALNUT AVE R OTHER SPORTS FACILITIES PORTOLA A N 6 S P 16 Irvine High School 4321 Walnut Ave. 949-936-7000 EDINGER O R PKWY T A 55 T 17 Northwood High School 4515 Portola Pkwy. 949-936-7200 I O N 3 C 18 University High School 4771 Campus Dr. 949-724-7600 O 9 R R BRYAN AVE ID REDHILL AVE 4 O 19 Woodbridge High School 2 Meadowbrook 949-936-7800 R COSTA MESA FWY 16 20 Concordia University Irvine 1530 Concordia West 949-854-8002 BARRANCA PKWY 13 TRABUCO ROAD 5 15 21 Irvine Valley College (IVC) 5500 Irvine Center Dr. -

A Guide to Irvine, California

A GUIDE TO IRVINE, CALIFORNIA Learn about life and things to do in Irvine, home to Regents Point, a be.group senior living community. IN THE HEART OF ORANGE COUNTY, Irvine is close to so many enjoyable things, from the beautiful coastline of its next-door neighbors, Laguna Beach and Newport Beach, to big-city entertainment in Los Angeles. Family-friendly attractions like Disneyland and Knott’s Berry Farm are less than 25 miles away. Irvine started as a ranching community, but the arrival of the University of California, Irvine in the 1960s quickly turned it into one of the country’s largest master-planned communities. Today, Irvine offers a world- class mix of education, business, outdoor recreation and family-friendly neighborhoods—all in a sunny, Mediterranean climate. The quality of life here is so high that it’s often ranked as one of the “Best Places to Live” by Money magazine, and the FBI has named Irvine as “America’s Safest City” every year for a decade. Regents Point, a be.group senior living community in Irvine, sits right next to the vast William R. Mason Regional Park, perfect for leisurely strolls and family picnics. A few blocks away is the University of California, Irvine, with plenty of opportunities for continuing education. Fine dining, shopping, arts and entertainment, and those famous golden beaches are just a few minutes’ drive away. THE BASICS 236,716 TOTAL/SENIOR RELIGION (Orange County): POPULATION: 3.8% 3.1% .8% Mormon Muslim Total Population Other 4.7% Senior Population Jewish 8.6% Protestant 17.8% Evangelical 61.2% 20,594 Catholic LOCAL MEDIA: MEDIAN INCOME: Orange County Register Los Angeles TimesO.C. -

For Lease Or Sale

IRVINE CENTER DRIVE IRVINE SPECTRUM, CALIFORNIA FOR LEASE OR SALE VIRTUAL TOUR Represented by: TRAVIS HAINING ALTON BURGESS Lee & Associates - Newport Beach Voit Real Estate Services 949.724.4711 949.263.5397 [email protected] [email protected] DRE #: 01483191 DRE #: 01717094 IRVINE CENTER DRIVE IRVINE SPECTRUM, CALIFORNIA 8845 Irvine Center Drive is a freestanding 36,146 SF creative office/flex building located in the heart of Irvine Spectrum. A truly rare property that fits the definition of “Corporate Headquarters”. Ideally situated on 2.35 acres with 5.4(A) zoning that allows for a variety uses including architects, engineers, technology companies, R&D and software development. This unique asset has the image, zoning, location and ideal creative improvements desired by market demand. Previously the headquarters for Boost Mobile, 8845 Irvine Center Drive is now available for a new company to call it home. Sale Price: $390 PSF / $14,096,940 Lease Rate: TBD BUILDING FEATURES Building Size 36,146 SF Available Office SF 9,033-27,113 SF Warehouse SF TBD Parking Ratio 4.6:1,000 Power 2,000 Amps / 480 V VIRTUAL TOUR Zoning 5.4 (Design Professionals) Street Frontage Yes (Irvine Center Dr. & Hubble) Elevator Yes Sprinklers Yes Ground Level Loading Possible PROPERTY OVERVIEW Located at a signalized light on Irvine Center art lab facility in their space. Approximately 50% Drive, 8845 Irvine Center Drive is one of the best of the building (the full top floor) is currently locations in all of Spectrum. A truly freestanding leased to a national data security firm, and can creative office building with flexible rear loading be made available October 2021 or potentially doors and warehouse potential that provides for sooner. -

Activity Guide

Activity Guide A complete listing of programs and services offered through the Community Services Department Many of the featured programs and activities are part of the City’s Healthy City Healthy Planet initiative. ith more than 100 W titles to choose from, families can find the perfect summer camp to satisfy everyone’s interest. See pages 48-59. 76 17 95 106 Swim Special Pets Registration Lessons Events rvine offers popular courses egister online at Ion dog manners, dog R irvinequickreg.org, by rvine offers Learn to ummer evenings are the obedience and puppy kin- phone at 949-724-6610 or I Swim programs for ages 6 Sperfect time to enjoy a dergarten. Ready for a new stop by one of the many com- months to adult. Classes are variety of outdoor movies family member? More than munity centers for assistance 25 or 40 minutes, weekdays and concerts with family, 500 animals are available (map on Pages 104-105). Regis- and on Saturdays. Classes friends and neighbors. See for adoption at the Super tration information on Pages fill fast; register early. See Pages 17-19. Pet Adoption event. See 106-107. Registration for sum- Pages 76-81. Page 95. mer classes begins May 11. The fall edition of Inside Irvine will be mailed the week of August 5. TO VIEW INSIDE IRVINE ONLINE, PLEASE VISIT CITYOFIRVINE.ORG/INSIDEIRVINE 16 Inside Irvine Summer 2015 For More Information: 949-724-6610 | irvinequickreg.org Summer 2015 ACTIVITY GUIDE EVENTS & FAMILY ACTIVITIES & FAMILY EVENTS caleNDAR OF eveNTS June 6 FREE Studio Arts Festival 9 a.m.–5 p.m. -

Ropy Important People

WOMEN-Guide:SupplementS.q 4/30/10 12:24 PM Page 23 WOMEN-Guide:SupplementS.q 4/30/10 12:24 PM Page 24 Page B-24 Get local breaking news: www.ocbj.com May 3, 2010 ORANGE COUNTY BUSINESS JOURNAL / WOMEN IN BUSINESS AWARDS ADVERTISING SUPPLEMENT Mobile Banking Helps Executives Make Smart Business Decisions by Susan Beat, CTP, AAP, Senior Vice President, Union Bank eople today are forever on the go. Our work week has gone from 9-5 to 24/7 is needed more than ever. “With todayʼs financial environment, it has become imper- and constant multitasking is practically a prerequisite for success. In short, ative for CEOs, CFOs and business owners to have a clear understanding of their we are always busy. companyʼs cash position on an hour-to-hour basis,” Swartz says. “Available funds This transformation in lifestyle has brought a change in the needs of finan- must be managed as efficiently as possible. Financial agility can be the key to keep- cial executives in all industries, and put technology in the driverʼs seat when ing operations running smoothly.” Pit comes to making the financial services experience as convenient and time-efficient Count on a secure network as possible. In the case of treasury management, executives and business owners on the go have had the option of using wireless connections to access key online banking Union Bankʼs Mobile Business Center deploys the same security measures as the services. bankʼs Online Business Center, with options for multifactor authentication, as well as Now, they can access these banking services directly through their smartphones.