Chapter 1 the Films

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

DOCUMENT RESUME RC 021 689 AUTHOR Many Nations

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 424 046 RC 021 689 AUTHOR Frazier, Patrick, Ed. TITLE Many Nations: A Library of Congress Resource Guide for the Study of Indian and Alaska Native Peoples of the United States. INSTITUTION Library of Congress, Washington, DC. ISBN ISBN-0-8444-0904-9 PUB DATE 1996-00-00 NOTE 357p.; Photographs and illustrations may not reproduce adequately. AVAILABLE FROM Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office, Washington, DC 20402. PUB TYPE Books (010) Guides Non-Classroom (055) -- Reference Materials Directories/Catalogs (132) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC15 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS *Alaska Natives; American Indian Culture; *American Indian History; American Indian Languages; *American Indian Studies; *American Indians; Annotated Bibliographies; Federal Indian Relationship; *Library Collections; *Resource Materials; Tribes; United States History IDENTIFIERS *Library of Congress ABSTRACT The Library of Congress has a wealth of information on North American Indian people but does not have a separate collection or section devoted to them. The nature of the Librarv's broad subject divisions, variety of formats, and methods of acquisition have dispersed relevant material among a number of divisions. This guide aims to help the researcher to encounter Indian people through the Library's collections and to enhance the Library staff's own ability to assist with that encounter. The guide is arranged by collections or divisions within the Library and focuses on American Indian and Alaska Native peoples within the United States. Each -

CANDID CAMERA Alan Funt, Alan Funt, Prod. Associated Artists Productions, Dist.Syndicated

BRAVE EAGLE Keith Larsen, Bert Wheeler, Kim Winona. Roy Rogers Frontier Productions,prod. CBS Television Film Sales, Inc., dist. Syndicated. Half-hour. Film. THE BRIGHTER DAY Blair Davies. Allan Potter, prod. Procter & Gamble Co. (Ivory Flakes, Cheer)- Young & Rubicam, Inc. CBS Network. Quarter-hour (5 days a week). Live. BRINGING UP YOUR BABY Documentary. Encyclopaedia Britannica Films, prod. Trans -LuxTelevision Corp., dist. Syndicated10 minutes. Film. BUCKSKIN Tommy Nolan, Sally Brophy. Robert Bassler, prod. Pillsbury Co.-Leo Burnett Co. NBCNet- work. Half-hour. Film. THE BUD WILKINSON SHOW Bud Wilkinson. Bud Wilkinson Productions, prod. Sportlite, Inc.,dist. Syndicated. Quarter-hour. Film. BUFFALO BILL, JR. Dick Jones, Flying "A" Pictures-Armand Schaefer, prod. CBS TelevisionFilm Sales, inc., dist. Syndicated. Half-hour. Film. BYLINE-STEVE WILSON (BIG TOWN) Mark Stevens. Mark Stevens TV Co., prod. M & A Alexander Products, dist. Syndicated. Half-hour. Film. CALIENTE RACES Joe Hernandez. Harry Lehman, prod. Cine-Tele Productions, dist. Syndicated.Half- hour. Film. CALIFORNIANS, THE Richard Coogan. Felix Feist, prod. Thomas J. Lipton Co., Singer Sewing Machine Co.-Young & Rubicam, Inc. NBC Network. Half-hour. Film. CAMERA THREE Various. Lewis Freedman, prod. Sustaining. CBS Network. Half-hour. Live. CANDID CAMERA Alan Funt, Alan Funt, prod. Associated Artists Productions, dist.Syndicated. Quarter-hour and half-hour. Film. CANINE COMMENTS David Wade. David Wade, prod. Louis Weiss & Co., dist. Syndicated. Quarter- hour. Film. CAPTAIN DAVID GRIEF Maxwell Reed. Guild Films Co., prod.-dist. Syndicated. Half-hour. Film. CAPTAIN KANGAROO Bob Keeshan. Jack Miller, prod. CBS Network. Participating. Three-quarter hour (Monday -Friday). Live. CAPTAIN QUEST AND HIS JUNIOR EXPLORERS Richard Coogan. -

Chapter Fourteen Men Into Space: the Space Race and Entertainment Television Margaret A. Weitekamp

CHAPTER FOURTEEN MEN INTO SPACE: THE SPACE RACE AND ENTERTAINMENT TELEVISION MARGARET A. WEITEKAMP The origins of the Cold War space race were not only political and technological, but also cultural.1 On American television, the drama, Men into Space (CBS, 1959-60), illustrated one way that entertainment television shaped the United States’ entry into the Cold War space race in the 1950s. By examining the program’s relationship to previous space operas and spaceflight advocacy, a close reading of the 38 episodes reveals how gender roles, the dangers of spaceflight, and the realities of the Moon as a place were depicted. By doing so, this article seeks to build upon and develop the recent scholarly investigations into cultural aspects of the Cold War. The space age began with the launch of the first artificial satellite, Sputnik, by the Soviet Union on October 4, 1957. But the space race that followed was not a foregone conclusion. When examining the United States, scholars have examined all of the factors that led to the space technology competition that emerged.2 Notably, Howard McCurdy has argued in Space and the American Imagination (1997) that proponents of human spaceflight 1 Notably, Asif A. Siddiqi, The Rocket’s Red Glare: Spaceflight and the Soviet Imagination, 1857-1957, Cambridge Centennial of Flight (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2010) offers the first history of the social and cultural contexts of Soviet science and the military rocket program. Alexander C. T. Geppert, ed., Imagining Outer Space: European Astroculture in the Twentieth Century (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2012) resulted from a conference examining the intersections of the social, cultural, and political histories of spaceflight in the Western European context. -

Documenting Apollo on The

NASA HISTORY DIVISION Office of External Relations volume 27, number 1 Fourth Quarter 2009/First Quarter 2010 FROM HOMESPUN HISTORY: THE CHIEF DOCUMENTING APOLLO HISTORIAN ON THE WEB By David Woods, editor, The Apollo Flight Journal Bearsden, Scotland In 1994 I got access to the Internet via a 0.014 Mbps modem through my One aspect of my job that continues to amaze phone line. As happens with all who access the Web, I immediately gravi- and engage me is the sheer variety of the work tated towards the sites that interested me, and in my case, it was astronomy we do at NASA and in the NASA History and spaceflight. As soon as I stumbled upon Eric Jones’s burgeoning Division. As a former colleague used to say, Apollo Lunar Surface Journal (ALSJ), then hosted by the Los Alamos NASA is engaged not just in human space- National Laboratory, I almost shook with excitement. flight and aeronautics; its employees engage in virtually every engineering and natural Eric was trying to understand what had been learned about working on science discipline in some way and often at the Moon by closely studying the time that 12 Apollo astronauts had spent the cutting edge. This breadth of activities is, there. To achieve this, he took dusty, old transcripts of the air-to-ground of course, reflected in the history we record communication, corrected them, added commentary and, best of all, man- and preserve. Thus it shouldn’t be surprising aged to get most of the men who had explored the surface to sit with him that our books and monographs cover such a and add their recollections. -

He KMBC-ÍM Radio TEAM

l\NUARY 3, 1955 35c PER COPY stu. esen 3o.loe -qv TTaMxg4i431 BItOADi S SSaeb: iiSZ£ (009'I0) 01 Ff : t?t /?I 9b£S IIJUY.a¡:, SUUl.; l: Ii-i od 301 :1 uoTloas steTaa Rae.zgtZ IS-SN AlTs.aantur: aTe AVSí1 T E IdEC. 211111 111111ip. he KMBC-ÍM Radio TEAM IN THIS ISSUE: St `7i ,ytLICOTNE OSE YN in the 'Mont Network Plans AICNISON ` MAISHAIS N CITY ive -Film Innovation .TOrEKA KANSAS Heart of Americ ENE. SEDALIA. Page 27 S CLINEON WARSAW EMROEIA RUTILE KMBC of Kansas City serves 83 coun- 'eer -Wine Air Time ties in western Missouri and eastern. Kansas. Four counties (Jackson and surveyed by NARTB Clay In Missouri, Johnson and Wyan- dotte in Kansas) comprise the greater Kansas City metropolitan trading Page 28 Half- millivolt area, ranked 15th nationally in retail sales. A bonus to KMBC, KFRM, serv- daytime ing the state of Kansas, puts your selling message into the high -income contours homes of Kansas, sixth richest agri- Jdio's Impact Cited cultural state. New Presentation Whether you judge radio effectiveness by coverage pattern, Page 30 audience rating or actual cash register results, you'll find that FREE & the Team leads the parade in every category. PETERS, ñtvC. Two Major Probes \Exclusive National It pays to go first -class when you go into the great Heart of Face New Senate Representatives America market. Get with the KMBC -KFRM Radio Team Page 44 and get real pulling power! See your Free & Peters Colonel for choice availabilities. st SATURE SECTION The KMBC - KFRM Radio TEAM -1 in the ;Begins on Page 35 of KANSAS fir the STATE CITY of KANSAS Heart of America Basic CBS Radio DON DAVIS Vice President JOHN SCHILLING Vice President and General Manager GEORGE HIGGINS Year Vice President and Sally Manager EWSWEEKLY Ir and for tels s )F RADIO AND TV KMBC -TV, the BIG TOP TV JIj,i, Station in the Heart of America sú,\.rw. -

Broadcasting Telecasting

YEAR 101RN NOSI1)6 COLLEIih 26TH LIBRARY énoux CITY IOWA BROADCASTING TELECASTING THE BUSINESSWEEKLY OF RADIO AND TELEVISION APRIL 1, 1957 350 PER COPY c < .$'- Ki Ti3dddSIA3N Military zeros in on vhf channels 2 -6 Page 31 e&ol 9 A3I3 It's time to talk money with ASCAP again Page 42 'mars :.IE.iC! I ri Government sues Loew's for block booking Page 46 a2aTioO aFiE$r:i:;ao3 NARTB previews: What's on tap in Chicago Page 79 P N PO NT POW E R GETS BEST R E SULTS Radio Station W -I -T -H "pin point power" is tailor -made to blanket Baltimore's 15 -mile radius at low, low rates -with no waste coverage. W -I -T -H reaches 74% * of all Baltimore homes every week -delivers more listeners per dollar than any competitor. That's why we have twice as many advertisers as any competitor. That's why we're sure to hit the sales "bull's -eye" for you, too. 'Cumulative Pulse Audience Survey Buy Tom Tinsley President R. C. Embry Vice Pres. C O I N I F I I D E I N I C E National Representatives: Select Station Representatives in New York, Philadelphia, Baltimore, Washington. Forloe & Co. in Chicago, Seattle, San Francisco, Los Angeles, Dallas, Atlanta. RELAX and PLAY on a Remleee4#01%,/ You fly to Bermuda In less than 4 hours! FACELIFT FOR STATION WHTN-TV rebuilding to keep pace with the increasing importance of Central Ohio Valley . expanding to serve the needs of America's fastest growing industrial area better! Draw on this Powerhouse When OPERATION 'FACELIFT is completed this Spring, Station WNTN -TV's 316,000 watts will pour out of an antenna of Facts for your Slogan: 1000 feet above the average terrain! This means . -

Why NASA Consistently Fails at Congress

W&M ScholarWorks Undergraduate Honors Theses Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects 6-2013 The Wrong Right Stuff: Why NASA Consistently Fails at Congress Andrew Follett College of William and Mary Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/honorstheses Part of the Political Science Commons Recommended Citation Follett, Andrew, "The Wrong Right Stuff: Why NASA Consistently Fails at Congress" (2013). Undergraduate Honors Theses. Paper 584. https://scholarworks.wm.edu/honorstheses/584 This Honors Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects at W&M ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Undergraduate Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of W&M ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Wrong Right Stuff: Why NASA Consistently Fails at Congress A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirement for the degree of Bachelors of Arts in Government from The College of William and Mary by Andrew Follett Accepted for . John Gilmour, Director . Sophia Hart . Rowan Lockwood Williamsburg, VA May 3, 2013 1 Table of Contents: Acknowledgements 3 Part 1: Introduction and Background 4 Pre Soviet Collapse: Early American Failures in Space 13 Pre Soviet Collapse: The Successful Mercury, Gemini, and Apollo Programs 17 Pre Soviet Collapse: The Quasi-Successful Shuttle Program 22 Part 2: The Thin Years, Repeated Failure in NASA in the Post-Soviet Era 27 The Failure of the Space Exploration Initiative 28 The Failed Vision for Space Exploration 30 The Success of Unmanned Space Flight 32 Part 3: Why NASA Fails 37 Part 4: Putting this to the Test 87 Part 5: Changing the Method. -

NOPL Summer Reading Guide

Summer Reading guide NOPL RECOMMENDED READS out of this world books for NOPl’s 2019 Summer Reading Program NOPL’S SUMMER READING PROGRAM 2019 The 2019 Summer Reading Program theme, “A Universe of Stories” helps people of all ages dream big, believe in themselves, and create their own story. This program also coincides with NASA’s 60 years of achievement and its celebration of the 50th anniversary of the Apollo 11 Moon Landing. Join NOPL, and over 16,000 libraries across the country, as we celebrate space exploration all summer long. Summer reading kicks off June 24. Stop by your nearest NOPL location to receive information about the program and pickup a calendar of events for the summer. Kids and teens can also sign up online to track books that they’ve read to earn prizes! To learn about the various Adult Summer Reading programs available visit your nearest NOPL location. VISIT NOPL.org/SRP 2 Contents 4 Early Literacy BookS Book recommendations for the tiniest explorers. 6 children’s books Book recommendations for children with imaginations as big as the universe. 8 teen reads Book recommendations for teens that reach for the stars. 10 adult reads Book recommendations for adults looking to escape. how to find books These book recommendations can be found at NOPL branches and through the catalog. If you‘re looking for a personal recommendation just speak with a librarian at any branch. Early Literacy BookS Book recommendations for the tiniest explorers. This Little Explorer: A Pioneer Primer by Joan Holub Little explorers discover the world. -

Retrofuture Hauntings on the Jetsons

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works Publications and Research Queens College 2020 No Longer, Not Yet: Retrofuture Hauntings on The Jetsons Stefano Morello CUNY Graduate Center How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/qc_pubs/446 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] de genere Rivista di studi letterari, postcoloniali e di genere Journal of Literary, Postcolonial and Gender Studies http://www.degenere-journal.it/ @ Edizioni Labrys -- all rights reserved ISSN 2465-2415 No Longer, Not Yet: Retrofuture Hauntings on The Jetsons Stefano Morello The Graduate Center, City University of New York [email protected] From Back to the Future to The Wonder Years, from Peggy Sue Got Married to The Stray Cats’ records – 1980s youth culture abounds with what Michael D. Dwyer has called “pop nostalgia,” a set of critical affective responses to representations of previous eras used to remake the present or to imagine corrective alternatives to it. Longings for the Fifties, Dwyer observes, were especially key to America’s self-fashioning during the Reagan era (2015). Moving from these premises, I turn to anachronisms, aesthetic resonances, and intertextual references that point to, as Mark Fisher would have it, both a lost past and lost futures (Fisher 2014, 2-29) in the episodes of the Hanna-Barbera animated series The Jetsons produced for syndication between 1985 and 1987. A product of Cold War discourse and the early days of the Space Age, the series is characterized by a bidirectional rhetoric: if its setting emphasizes the empowering and alienating effects of technological advancement, its characters and its retrofuture aesthetics root the show in a recognizable and desirable all-American past. -

![Archons (Commanders) [NOTICE: They Are NOT Anlien Parasites], and Then, in a Mirror Image of the Great Emanations of the Pleroma, Hundreds of Lesser Angels](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/8862/archons-commanders-notice-they-are-not-anlien-parasites-and-then-in-a-mirror-image-of-the-great-emanations-of-the-pleroma-hundreds-of-lesser-angels-438862.webp)

Archons (Commanders) [NOTICE: They Are NOT Anlien Parasites], and Then, in a Mirror Image of the Great Emanations of the Pleroma, Hundreds of Lesser Angels

A R C H O N S HIDDEN RULERS THROUGH THE AGES A R C H O N S HIDDEN RULERS THROUGH THE AGES WATCH THIS IMPORTANT VIDEO UFOs, Aliens, and the Question of Contact MUST-SEE THE OCCULT REASON FOR PSYCHOPATHY Organic Portals: Aliens and Psychopaths KNOWLEDGE THROUGH GNOSIS Boris Mouravieff - GNOSIS IN THE BEGINNING ...1 The Gnostic core belief was a strong dualism: that the world of matter was deadening and inferior to a remote nonphysical home, to which an interior divine spark in most humans aspired to return after death. This led them to an absorption with the Jewish creation myths in Genesis, which they obsessively reinterpreted to formulate allegorical explanations of how humans ended up trapped in the world of matter. The basic Gnostic story, which varied in details from teacher to teacher, was this: In the beginning there was an unknowable, immaterial, and invisible God, sometimes called the Father of All and sometimes by other names. “He” was neither male nor female, and was composed of an implicitly finite amount of a living nonphysical substance. Surrounding this God was a great empty region called the Pleroma (the fullness). Beyond the Pleroma lay empty space. The God acted to fill the Pleroma through a series of emanations, a squeezing off of small portions of his/its nonphysical energetic divine material. In most accounts there are thirty emanations in fifteen complementary pairs, each getting slightly less of the divine material and therefore being slightly weaker. The emanations are called Aeons (eternities) and are mostly named personifications in Greek of abstract ideas. -

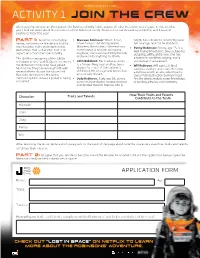

ACTIVITY 1 Join the Crew

REPRODUCIBLE ACTIVITY ACTIVITY 1 Join the Crew After crash-landing on an alien planet, the Robinson family fights against all odds to survive and escape. In this activity, you’ll find out more about the members of the Robinson family. Season 1 is now streaming on Netflix, and Season 2 premieres later this year. Part 1: Read the information • Maureen Robinson: Smart, brave, bright, has a desire to constantly prove below, and then use the details to fill in adventurous, and strong-willed, her courage, and can be stubborn. the character traits and talents table. Maureen, the mother, is the mission • Penny Robinson: Penny, age 15, is a Remember that a character trait is an commander. A brilliant aerospace well-trained mechanic. She is cheerful, aspect of a character’s personality. engineer, she loves her family fiercely outgoing, witty, and brave. She has and would do anything for them. The Netflix reimagining of the 1960s a talent for problem-solving, and is television series “Lost in Space” features • John Robinson: Her husband, John, somewhat of a daredevil. the Robinson family who have joined is a former Navy Seal and has been • Will Robinson: Will, age 11, is kind, Mission 24. They are leaving Earth with absent for much of the children’s cautious, creative, and smart. He forms several others aboard the spacecraft childhood. He is tough and smart, but a tight bond with an alien robot that he Resolute destined for the Alpha emotionally distant. saves from destruction during a forest Centauri system, where a planet is being • Judy Robinson: Judy, age 18, serves fire. -

Advertising and Public Relations Law

Advertising and Public Relations Law Addressing a critical need, Advertising and Public Relations Law explores the issues and ideas that affect the regulation of advertising and public relations speech. Coverage includes the categorization of different kinds of speech afforded varying levels of First Amendment protection; court-created tests for laws and reg- ulations of speech; and non-content-based restrictions on speech and expression. Features of this edition include: • A discussion in each chapter of new-media implications • Extended excerpts from major court decisions • Appendices providing — a chart of the judicial system — a summary of the judicial process — an overview of alternative dispute resolution mechanisms — the professional codes for media industry and business associations, including the American Association of Advertising Agencies, the Public Relations Society of America and the Society of Professional Journalists • Online resources for instructors. The volume is developed for upper-level undergraduate and graduate students in media, advertising and public relations law or regulation courses. It also serves as an essential reference for advertising and public relations practitioners. Roy L. Moore is professor of journalism and dean of the College of Mass Communication at Middle Tennessee State University. He holds a Ph.D. in mass communication from the University of Wisconsin and a juris doctorate from the Georgia State University College of Law. Carmen Maye is a South Carolina-based lawyer and an instructor in the School of Journalism and Mass Communications at the University of South Carolina, where she teaches courses in media law and advertising. Her undergraduate degree is from the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.