Maryland Historical Trust Inventory No

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mixed-Use Zone Report for the Town of Middletown, Delaware

Mixed-Use Zone Report for the Town of Middletown, Delaware October 2018 Prepared by Sean O’Neill, AICP, Policy Scientist Institute for Public Administration School of Public Policy & Administration College of Arts & Sciences University of Delaware Mixed-Use Zone Report for the Town of Middletown, Delaware October 2018 Prepared by Sean O’Neill, AICP, Policy Scientist Institute for Public Administration School of Public Policy & Administration College of Arts & Sciences University of Delaware Mixed-Use Zone Report for the Town of Middletown, Delaware Acknowledgements As the director of the Institute for Public Administration (IPA) at the University of Delaware, I am pleased to present this Mixed-Use Zone Report for the Town of Middletown, Delaware. The document is a follow-up report to IPA’s 2017 Middletown Multifamily Housing Analysis, which recommended that the town consider adopting a mixed-use zoning district. Middletown has experienced unprecedented growth over the past two decades. This growth presents both challenges and opportunities, such as establishing new and exciting areas within town for residents and visitors. Given the large amount of residential growth in the surrounding area, commercial development has followed and is likely to continue. The new Route 301 highway is likely to attract commercial developers seeking to build retail, office, and multifamily uses that will have quicker access to the I-95 Corridor than has previously been possible in Middletown’s Westtown area. In an effort to address the challenges and opportunities resulting from growth, this report outlines the key aspects of a new mixed-use zoning district that would allow for more density in some of the town’s growth areas while providing for the flexibility needed to create new walkable and attractive neighborhoods. -

IN THIS ISSUE: Arlington, VA 22216 BULK RATE U.S

NEWSLETTER OF THE NATIONAL CAPITAL CHAPTER MARCH/APRIL 1984 dcr bavemche Box 685 IN THIS ISSUE: Arlington, VA 22216 BULK RATE U.S. POSTAGE PAID Auto Show Report ARLINGTON, VA May Driving School PERMIT* 2314 Spring Membership Contest YNN30168*84*07*4 325e Preview JOHN B. CARPENTER VASCAR Speed Trap RURAL ROUTE 2 BOX 607N WHITE PLAINES, P1D Z0695 SALES LEASING SERVICE PARTS "Much More" Service Program Means Lower and Exact Pricing Before We Start Service While-U-Wait (in most cases) Appointments LARGEST PARTS DEPARTMENT IN AREA © t AUTO SALES 11605 Old Georgetown Road, Rockville, Md. 20852 770-6100 2 Coming Events G.W. MOTORS & VDO FACTORY TOUR March 17, 1983 Join us for a St. Patrick's Day drive to Winchester, Virginia to tour the VDO factory (home of great gauges) (kr bavensche and to have wine and cheese at G.W. Motors. The plan is is the official publication of the National Capital Chapter of the BMW Car to drive directly from the Roy Rogers rendezvous to Win Club of America, Inc. and is not in any way connected with the Bayerische chester in order to arrive at 11:00am. Departure from Roy Motoren Werke AG or BMW of North America, Inc. It is provided by and for the club membership only. All ideas, opinions and suggestions Rogers 9:30a, from Winchester 3:00pm. expressed in regard to technical or other matters are solely those of the Directions: Meet at Roy Rogers in Greenbrier Shop authors and no authentication or factory approval are implied unless ping Center, Route 50, at 9:30am sharp. -

IN THIS ISSUE: Arlington, VA 22216 U.S

MARCH/APRIL 1983 NEWSLETTER OF THE NATIONAL CAPITAL CHAPTER i t t Box 685 BULK RATE IN THIS ISSUE: Arlington, VA 22216 U.S. POSTAGE Life with a BMW 323i Cabriolet PAID ARLINGTON. VA Fighter pilot's BMW 528e PERMIT* 2314 Rambling Ruminations ^Jech Sessions mi THE NEXT ISSUE: The Crash of My 320S BMW M1 Testdrive COMING EVENTS SPRING TOUR April 16, 1983 On Saturday, April 16, 1983 at 10:00 a.m. meet at Precision BMW, Frederick, Maryland (301) 694-7400, 428-0400 D.C. After the arrival of all the participants we will drive with enthusiasm through some of Western Mary deis the officiarl publicatio bayerischn of the National Capital Chapter of the BMWe Car land's most scenic roads. Then later at approximately Club of America, Inc. and is not in any way connected with the Bayerische Motoren Werke AG or BMW of North America, Inc. It is provided by and 1:30 p.m. we will arrive at Warner's German Restaurant in for the club membership only. All ideas, opinions and suggestions Cresaptown, 7 miles South of Cumberland, Maryland. expressed In regard to technical or other matters are solely those of the There The Club will provide lunch and refreshments. authors and no authentication or factory approval are implied unless specifically stated.'The club assumes no liability for any of the information Directions: From Baltimore take 70 West to Route contained herein. Modifications within the warranty period may void 355/85. Right on 85 to Precision BMW on your left. the warranty. From Washington take 270 North to Route 85 North. -

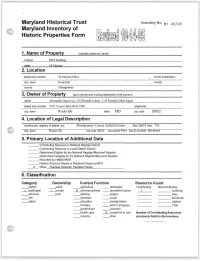

Revised 10-14-05

Maryland Historical Trust Inventory No. M: 26/45 Maryland Inventory of Historic Properties Form Revised 10-14-05 1. Name of Property (indicate preferred name) historic IBM Building other 50 Monroe 2. Location street and number 50 Monroe Place not for publication city, town Rockville vicinity county Montgomery 3. Owner of Property (give names and mailing addresses of all owners) name Alexander Guss et al., C/O Ronald Cohen, C/O Ronald Cohen Mgmt street and number 2701 Tower Oaks Blvd. #200 telephone city, town Rockville state MD zip code 20852 4. Location of Legal Description courthouse, registry of deeds, etc. Montgomery County Judicial Center liber 29975 folio 776 city, town Rockville taxmapGR32 tax parcel P401 tax ID number 00144444 5. Primary Location of Additional Data . Contributing Resource in National Register District . Contributing Resource in Local Historic District Determined Eligible for the National Register/Maryland Register Determined Ineligible for the National Register/Maryland Register . Recorded by HABS/HAER Historic Structure Report or Research Report at MHT X Other: Peerless Rockville. Peerless Places 6. Classification Category Ownership Current Func tior i Resource Count district public agriculture landscape Contributing Noncontributing x buildina(s) x private X commerce/trade recreation/culture 1 buildinqs structure both defense religion sites site domestic social structures object education transportation objects funerary work in progress Total government unknown health care X vacant/not in use Number of Contributing Resources industry other: previously listed in the Inventory 7. Description Inventory No. M: 26-45 Condition excellent deteriorated good ruins X fair _ altered Prepare both a one paragraph summary and a comprehensive description of the resource and its various elements as it exists today. -

IN THIS ISSUE: Arlington, VA 22216 BULK RATE U.S

NEWSLETTER OF THE NATIONAL CAPITAL CHAPTER JAN/FEB 1984 dcr bavcrischc Box 685 IN THIS ISSUE: Arlington, VA 22216 BULK RATE U.S. POSTAGE PAID Winery Tour YNN30168*84*07*4 ARLINGTON, VA JOHN B. CARPENTER PERMIT#2314 Annual Election RURAL ROUTE 2 Rambling Ruminations BOX 607N Gray Market Update WHITE PLAINES, HO 20695 1984 Predictions AU1DSAL£S 770-6100 DATSUN — BMW — SAAB SALES — LEASING — SERVICE — PARTS "Much More" Service Program "Much More" Means Lower and Exact Pricing Before We Start Service While-U-Wait (in most cases) Appointments SAAB DATSUN ©II AJIOSALES 11605 Old Georgetown Rd., Rockville, Md. 20852 770-6100 '^ ^ master charge 1 AUTO REPAIR AUiU HtrtXIR ^^•^^v 2 COMING EVENTS TECH SESSION January 28, 1984 J & F Motors will host session on engine modifica tions — good or bad? Another topic is A/C units — rebuilding or replacing? J & F is at 4076 South Four Mile Run Drive in Arlington. Time: 9:30a — l:30p dcis the officiarl publicatio bayenschn of the National Capital Chapter of the BMWe Car Club of America, Inc. and is not in any way connected with the Bayerische Directions: From D.C. take 1-395 South to Glebe Motoren Werke AG or BMW of North America, Inc. It is provided by and Road/Shirlington, follow signs to Shirlington, turn right for the club membership only. All ideas, opinions and suggestions at the light onto Shirlington Road, then first left at South expressed in regard to technical or other matters are solely those of the Four Mile Run Drive, about 1.6 miles on your left. -

Metrorail Station Area Planning a Metrorail Before-And-After Study Report

Metrorail Station •S. Department of ansportation Area Planning A Metrorail BetoferandiAfter Study Report JUL 3 I August 1983 library ' Status of Jf' Shady Grove mile Metro system \ Uv^yU December 1982 Red Line — Glenmont/Shady Grove Blue Line — Addison Road/Huntington Orange Line — New Carrollton/Vienna Green Line — Greenbelt/Branch Avenue Yellow Line — Franconia-Springfield/Greenbelt PRINCE GEORGE’S COUNTY MARYLAND FAIRFAX COUNTY Dunn Loring Vienna JitxacosUa ms peniwKw ;ti; -»///////„„^ Atabama Ave vjNaylor Rd FAIRFAX ^ CITY I w Congress% m , ^ Heights ® Branch Awe* Braddock ALEXANDRIA St Barnabas m Van Dorn St Road •The alignment and terminus of the Green Line has not determined Rosecroft been finally .O^OOOOOOOOV^in, ® The WMATA Board of Direc- ^ tors has proposed changes Fairfax Huntington^rV ; 1993 to this route,one of which County would result in an align- o ment terminating at o ,tatei83 \V' Rosecroft o J o Eisenhower Ave Franconia-Springlield ^ VIRGINIA MARYLAND LEGEND 1. Farragut North 10. Waterfront Operating Lines 39,12 miles 44 stations Total mileage— 101.18 2. Farragut West 11. Navy Yard 3. McPherson Square 12. Eastern Market 4. Center 13. Potomac Ave Under Construction or Substantially Complete Total stations—86 Metro 5. Federal Triangle 14. Stadium-Armory 32.4 miles 22 stations 6. Smithsonian 15. Archives Square 0000®00 Under Final Design 19 78 miles 12 stations 7. L'Enfant Plaza 16. Judiciary 8. Federal Center SW 17. Gallery Place Ml Vernon llllllllllllllt®llllllll Remainder of System 9 88 miles 8 stations 9. Capitol South 18. Sq-UDC Area Transit Authority 1986 Projected start of operations for this segment based Wash ngton Metropolitan all stations M D.C. -

Rockville Town Square: a Case Study in Transit Oriented Development

Development Aimee DarrowAimee Study in Transit Oriented Oriented Transit Study in Rockville Town Square: A Case A Case Square: Town Rockville This case study examines Phase I of the Rockville, Maryland Town Center Master Plan, Rockville Town Square. The master plan establishes a 60-acre mixed-used development district in Rockville’s downtown. This study looks at the first project to be developed since the adoption of the master plan and its success as a transit-oriented development. MSRE Research Project Fall, 2009 P a g e | 2 Table of Contents Executive Summary .......................................................................................................... 3 What is Transit-Oriented Development? ........................................................................... 5 Literature Review .............................................................................................................. 7 The Case Study ............................................................................................................... 17 Analysis .......................................................................................................................... 30 Conclusion ...................................................................................................................... 38 Bibliography .................................................................................................................... 42 TOD Typology…………………………………………………………………………….……Appendix A City of Rockville Land Use Map.…………………………………………………….…….Appendix -

Market and Transit-Oriented Development Potential, Priorities

$23.00 Subregion 4 (Central Avenue-Metro Blue Line Corridor) Transit-Oriented Development Implementation Project Market and Transit-Oriented Development Potential, Priorities, and Strategies Study PART I: Executive Summary PART II: Market and TOD Potential PART III: Financial Analysis PART IV: Action and Implementation Plan PART V: Branding Study ent Transit- Oriented Developm THE MARYLAND-NATIONAL CAPITAL PARK AND PLANNING COMMISSION PRINCE GEORGE’S COUNTY PLANNING DEPARTMENT www.pgplanning.org/pgco TODJuly 2014 Abstract Title: Central Avenue-Metro Blue Line Corridor TOD Implementation Market and Transit-Oriented Development Potential, Priorities, and Strategies Study Author: The aryland-NationalM Capital Park and Planning Commission Subject: Project Mobility Study Date: July 2014 Source of Copies: The aryland-NationalM Capital Park and Planning Commission 14741 Governor Oden Bowie Drive Upper Marlboro, MD 20772 Series Number: 440142306 Number of Pages: 244 Abstract: TheMarket and Transit-Oriented Development (TOD) Potential, Priorities, and Strategies Study will support the Subregion 4 Central Avenue-Metro Blue Line Corridor TOD Implementation Project. Planning at the station level will be formed by corridor-level planning and will include an analysis of the development potential at the following Blue Line Metro Stations: Capitol Heights, Addison Road-Seat Pleasant, and Morgan Boulevard. Development opportunities at the Largo Town Center station are further defined in the 2013 Approved Largo Town Center Sector Plan and Sectional Map -

Office Market Assessment, Montgomery County, Maryland

Office Market Assessment, Montgomery County, Maryland Prepared for Montgomery County Planning Department June 2, 2015 Montgomery County’s Challenge .......................................................................................... 1 Types of Office Tenants ........................................................................................................ 3 Demand Forces...................................................................................................................... 4 Employment-Driven Demand ........................................................................................... 4 Shifting Usage Patterns .................................................................................................... 5 Timing of Change .............................................................................................................. 6 Supply Forces ........................................................................................................................ 6 Sustainability .................................................................................................................... 6 Shifting Locational Demand ............................................................................................. 6 Construction in Excess of Demand ................................................................................... 7 Federal Space Cutbacks .................................................................................................... 7 Major Vacancies................................................................................................................ -

Effects of the Recession on Maryland Communities Hearings

EFFECTS OF THE RECESSION ON MARYLAND COMMUNITIES HEARINGS BEFORE THE SUBCOMMITTEE ON INVESTMENT, JOBS, AND PRICES OF THO JOINT ECONOMIC COMMITTEE CONGRESS OF THE UNITED STATES NINETY-SEVENTH CONGRESS FIRST SESSION JANUARY 11, 12, 14, AND 15, 1982 Printed for the use of the Joint Economic Committee U.S; GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE 95-758 WASHINGTON: 1982 ,&.*. 'R 9 r `4 JOINT ECONOMIC COMMITTEE (Created pursuant to sec. 5(a) of Public Law 304, 79th Cong.) HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES SENATE HENRY S. REUSS, Wisconsin, Chairman ROGER W. JEPSEN, Iowa, Vice Chairman RICHARD BOLLING, Missouri WILLIAM V. ROTH, JR., Delaware LEE H. HAMILTON, Indiana JAMES ABDNOR, South Dakota GILLIS W. LONG, Louisiana STEVEN D. SYMMS, Idaho PARREN J. MITCHELL, Maryland PAULA HAWKINS, Florida FREDERICK W. RICHMOND, New York MACK MATTINGLY, Georgia CLARENCE J. BROWN. Ohio LLOYD BENTSEN, Texas MARGARET M. HECKLER, Massachusetts WILLIAM PROXMIRE, Wisconsin JOHN H. ROUSSELOT, California EDWARD M. KENNEDY, Massachusetts CHALMERS P. WYLIE, Ohio PAUL S. SARBANES, Maryland JAMES K. GALBRAITH, Executive Director BRUCE R. BARTLETT, Deputy Director SUBCOMMITTEE ON INVESTMENT, JOBS, AND PRICES HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES SENATE HENRY S. REUSS, Wisconsin, Chairman EDWARD M. KENNEDY, Massachusetts, PARREN J. MITCHELL, Maryland Vice Chairman CHALMERS P. WYLIE, Ohio PAUL S. SARBANES, Maryland CLARENCE J. BROWN, Ohio WILLIAM V. ROTH, JR., Delaware MARGARET M. HECKLER, Massachusetts (I) CONTENTS WITNESSES AND STATEMENTS MONDAY, JANUARY 11, 1982 Sarbanes, Hon. Paul S., member of the Subcommittee on Investment, Page Jobs, and Prices, presiding: Opening statement- 1 Heintz, Frank O., executive director, Employment Security Administra- tion, Maryland Department of Human Resources, Baltimore, Md 3 Hutchinson, Donald P., Baltimore County executive, Towson, Md -12 Wasserman, Mark, representing Hon. -

In the Next Issue: John B

Box 685 BULK RATE IN THIS ISSUE: Arlington, VA 22216 U.S. POSTAGE BMW 533i Testdrive PAID ARLINGTON, VA BMW 320S Wrecker PERMIT* 2314 Protecting Your BMW Club Member Discounts YNN30168*83«Q7*4 IN THE NEXT ISSUE: JOHN B. CARPENTER The Crash of My 320S: RURAL ROUTE 2 A Thorough Repair Story BOX 607N WHITE PLAINES, HD 20695 i COMING EVENTS TECHNICAL SESSION January 29, 1983 A technical session on rebuilding BMW engines will be held on Saturday, January 29, 1983, 9:30 a.m. thru 1:00 p.m., at J&F Motors Ltd., 4076 S. Four Mile Run Drive, Arlington, VA (671-7757). In addition to tune-ups and regular maintenance J&F is one of the largest BMW engine rebuilding firms in the D.C. area. Come learn what i(fas the officia*l publicatio bavemchn of the National Capital Chapter of the BMWe Car Club of America, Inc. and is not in any way connected with the Bayerische is entailed in dismantling and reconditioning your engine Motoren Werke AG or BMW of North America, Inc. It is provided by and when the inevitable occurs. A 20% discount will be of for the club membership only. All ideas, opinions and suggestions fered on all parts in stock! expressed in regard to technical or other matters are solely those of the authors and no authentication or factory approval are implied unless Directions: From D.C. take 395 South to Glebe Rd./ specifically stated. The club assumes no liability for any of the information Shirlington exit. Follow signs to Shirlington. -

Retail Market Analysis

RETAIL MARKET ANALYSIS OAKVILLE TRIANGLE / ROUTE 1 CORRIDOR PLANNING STUDY AREA ALEXANDRIA, VIRGINIA April 27, 2015 PREPARED BY DELTA ASSOCIATES FOR: STONEBRIDGECARRAS 7200 Wisconsin Avenue, Suite 700 Bethesda, MD 20814 #15228 1717 K STREET, NW, SUITE 1010 | WASHINGTON, DC 20006 P: 202.778.3100 | WWW.DELTAASSOCIATES.COM TABLE OF CONTENTS PAGE Letter of Findings .......................................................................................................................................................... 1 Background and Purpose ................................................................................................................................ 1 Summary of Findings ....................................................................................................................................... 2 Washington Metro Area Economic Overview ............................................................................................... 3 Washington Metro Area Retail Market Overview ......................................................................................... 4 Area Evaluation ............................................................................................................................................... 5 Study Area Description and Development Plans for the Subject .................................................................. 8 Trade Area Definition ...................................................................................................................................... 11