Rockville Town Square: a Case Study in Transit Oriented Development

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mixed-Use Zone Report for the Town of Middletown, Delaware

Mixed-Use Zone Report for the Town of Middletown, Delaware October 2018 Prepared by Sean O’Neill, AICP, Policy Scientist Institute for Public Administration School of Public Policy & Administration College of Arts & Sciences University of Delaware Mixed-Use Zone Report for the Town of Middletown, Delaware October 2018 Prepared by Sean O’Neill, AICP, Policy Scientist Institute for Public Administration School of Public Policy & Administration College of Arts & Sciences University of Delaware Mixed-Use Zone Report for the Town of Middletown, Delaware Acknowledgements As the director of the Institute for Public Administration (IPA) at the University of Delaware, I am pleased to present this Mixed-Use Zone Report for the Town of Middletown, Delaware. The document is a follow-up report to IPA’s 2017 Middletown Multifamily Housing Analysis, which recommended that the town consider adopting a mixed-use zoning district. Middletown has experienced unprecedented growth over the past two decades. This growth presents both challenges and opportunities, such as establishing new and exciting areas within town for residents and visitors. Given the large amount of residential growth in the surrounding area, commercial development has followed and is likely to continue. The new Route 301 highway is likely to attract commercial developers seeking to build retail, office, and multifamily uses that will have quicker access to the I-95 Corridor than has previously been possible in Middletown’s Westtown area. In an effort to address the challenges and opportunities resulting from growth, this report outlines the key aspects of a new mixed-use zoning district that would allow for more density in some of the town’s growth areas while providing for the flexibility needed to create new walkable and attractive neighborhoods. -

IN THIS ISSUE: Arlington, VA 22216 BULK RATE U.S

NEWSLETTER OF THE NATIONAL CAPITAL CHAPTER MARCH/APRIL 1984 dcr bavemche Box 685 IN THIS ISSUE: Arlington, VA 22216 BULK RATE U.S. POSTAGE PAID Auto Show Report ARLINGTON, VA May Driving School PERMIT* 2314 Spring Membership Contest YNN30168*84*07*4 325e Preview JOHN B. CARPENTER VASCAR Speed Trap RURAL ROUTE 2 BOX 607N WHITE PLAINES, P1D Z0695 SALES LEASING SERVICE PARTS "Much More" Service Program Means Lower and Exact Pricing Before We Start Service While-U-Wait (in most cases) Appointments LARGEST PARTS DEPARTMENT IN AREA © t AUTO SALES 11605 Old Georgetown Road, Rockville, Md. 20852 770-6100 2 Coming Events G.W. MOTORS & VDO FACTORY TOUR March 17, 1983 Join us for a St. Patrick's Day drive to Winchester, Virginia to tour the VDO factory (home of great gauges) (kr bavensche and to have wine and cheese at G.W. Motors. The plan is is the official publication of the National Capital Chapter of the BMW Car to drive directly from the Roy Rogers rendezvous to Win Club of America, Inc. and is not in any way connected with the Bayerische chester in order to arrive at 11:00am. Departure from Roy Motoren Werke AG or BMW of North America, Inc. It is provided by and for the club membership only. All ideas, opinions and suggestions Rogers 9:30a, from Winchester 3:00pm. expressed in regard to technical or other matters are solely those of the Directions: Meet at Roy Rogers in Greenbrier Shop authors and no authentication or factory approval are implied unless ping Center, Route 50, at 9:30am sharp. -

NCHRP Report 350, Which Specifies Speeds, Angles of Collision, and Vehicle Types, As Well As Defines Success Or Failure in the Testing

93 H. CASE STUDIES The following is a selection of case studies that illustrate application of the principles and thought process A B C D E F G H behind CSD/CSS. The case stud- Effective Reflecting Achieving Ensuring Safe ies were assembled from materials Introduction About this Decision Community Environmental and Feasible Organizational Case Appendices and interviews conducted with pilot to CSD Guide Making Values Sensitivity Solutions Needs Studies state representatives, as well as with Management Structure other agencies contacted during the research project. The case studies Problem Definition are geographically diverse. They Project Development and illustrate a wide range of project Evaluation Framework contexts, from rural roads to urban Alternatives Development streets. They demonstrate that one can be context sensitive when dealing Alternatives Screening with a freeway, an arterial, or a local Evaluation and Selection road. In one case, they show that the Implementation mission of a transportation agency ���������� can and should go beyond providing for safe and efficient transportation. They represent both small projects and substantial efforts. Most of all, the case studies show how project success can be achieved by following the framework discussed here, and applying the right resources to solve a problem. National Cooperative Highway Research Program Report 480 Section H: Case Studies 94 This page intentionally left blank Section H: Case Studies A Guide to Best Practices for Achieving Context Sensitive Solutions 95 CASE STUDY NO. 1 MERRITT PARKWAY GATEWAY PROJECT GREENWICH, CONNECTICUT Both the volume of traffic and its character and operations SETTING have changed over time. The Parkway now carries traffic The Merritt Parkway (The Parkway) was constructed in in excess of 50,000 vehicles per day in some segments. -

IN THIS ISSUE: Arlington, VA 22216 U.S

MARCH/APRIL 1983 NEWSLETTER OF THE NATIONAL CAPITAL CHAPTER i t t Box 685 BULK RATE IN THIS ISSUE: Arlington, VA 22216 U.S. POSTAGE Life with a BMW 323i Cabriolet PAID ARLINGTON. VA Fighter pilot's BMW 528e PERMIT* 2314 Rambling Ruminations ^Jech Sessions mi THE NEXT ISSUE: The Crash of My 320S BMW M1 Testdrive COMING EVENTS SPRING TOUR April 16, 1983 On Saturday, April 16, 1983 at 10:00 a.m. meet at Precision BMW, Frederick, Maryland (301) 694-7400, 428-0400 D.C. After the arrival of all the participants we will drive with enthusiasm through some of Western Mary deis the officiarl publicatio bayerischn of the National Capital Chapter of the BMWe Car land's most scenic roads. Then later at approximately Club of America, Inc. and is not in any way connected with the Bayerische Motoren Werke AG or BMW of North America, Inc. It is provided by and 1:30 p.m. we will arrive at Warner's German Restaurant in for the club membership only. All ideas, opinions and suggestions Cresaptown, 7 miles South of Cumberland, Maryland. expressed In regard to technical or other matters are solely those of the There The Club will provide lunch and refreshments. authors and no authentication or factory approval are implied unless specifically stated.'The club assumes no liability for any of the information Directions: From Baltimore take 70 West to Route contained herein. Modifications within the warranty period may void 355/85. Right on 85 to Precision BMW on your left. the warranty. From Washington take 270 North to Route 85 North. -

BETHESDA BRAC IMPROVEMENTS BETHESDA TROLLEY TRAIL CONNECTIONS and PASSENGER DROP-OFF LOOP a $1,100,000 Grant Proposal to the Of

BETHESDA BRAC IMPROVEMENTS BETHESDA TROLLEY TRAIL CONNECTIONS AND PASSENGER DROP-OFF LOOP A $1,100,000 Grant Proposal to the Office of Economic Adjustment, U.S. Department of Defense Submitted by the Maryland State Highway Administration, Maryland, Department of Transportation October 7, 2011 RE: Federal Register Document 2011-184000: Volume 70, Number 140, July 21, 2011 Notice of Federal Funding Opportunity (FFO) for construction of Transportation Infrastructure Improvements Associated with medical facilities related to recommendations of the 2005 Defense Base Closure and Realignment Commission. A. POINT OF CONTACT : Barb Solberg, Division Chief Highway Design Division Office of Highway Development State Highway Administration 707 North Calvert St. Baltimore MD, 21202 410-545-8830 [email protected] B. EXISTING OR PROJECTED TRANSPORTATION INFRASTRUCTURE ISSUE : • Relocation of Walter Reed The Bethesda Base Realignment and Closure (BRAC) improvement projects are intended to mitigate gridlock, improve pedestrian access and safety, and support multi-modal transportation systems around the new federally-mandated Walter Reed National Military Medical Center. One of the most noteworthy moves mandated by the 2005 BRAC law was the closure of the Walter Reed Army Medical Center (WRAMC) in Washington, D.C., with the relocation of most of its functions and personnel to the campus of the National Naval Medical Center (NNMC) in Bethesda, Montgomery County, Maryland, establishing the joint service Walter Reed National Military Medical Center (WRNMMC). The intent of consolidating these two premier institutions was to establish the modern “crown jewel” of military medical care and research combining the best of Army, Navy and Air Force practices that could serve the needs of the American military facing new kinds of catastrophic injuries in the era following September 11, 2001. -

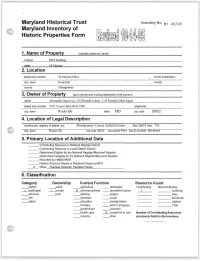

Maryland Historical Trust Inventory No

Capsule Summary Inventory No. F-7-139 Monocacy Crossing Urbana Pike and Monocacy River Frederick County, MD Ca. 1750-present; 1864 Access: Public Monocacy Crossing consists of a collection of road traces and existing roads, a ferry crossing site, fording place and the current steel truss bridge which carries Maryland Route 355 across the Monocacy River. These crossings date from as early as the mid 18 century and continue to the mid 20th century for the bridge that remains in daily use. On the segment of the Monocacy that flows through the battlefield are two fording places that were known as early as the 1730s. One was located just below the mouth of Ballenger Creek and the other a short distance downstream from the present Maryland Route 355 bridge. The Ballenger Creek area ford was used by Confederate forces during the Battle of Monocacy. The other ford is recorded on land plats and the trace of the old road leading to it is still evident on the landscape. Until the 1830s, when the B&O Railroad was constructed, there was ferry service at this upper ford. The battlefield landscape is largely pastoral, with wooded hillsides and fields of hay, corn and wheat, as well as pasture lands for dairy cattle. The Monocacy River bisects the scene. The battlefield is also bisected with 1-270 a busy commuter route to Washington DC, which crosses the Monocacy approximately lA mile south of the historic crossing place. Outside the limit of the battlefield the surrounding landscape is fragmented, lost in places to intense commercial and residential development. -

Revised 10-14-05

Maryland Historical Trust Inventory No. M: 26/45 Maryland Inventory of Historic Properties Form Revised 10-14-05 1. Name of Property (indicate preferred name) historic IBM Building other 50 Monroe 2. Location street and number 50 Monroe Place not for publication city, town Rockville vicinity county Montgomery 3. Owner of Property (give names and mailing addresses of all owners) name Alexander Guss et al., C/O Ronald Cohen, C/O Ronald Cohen Mgmt street and number 2701 Tower Oaks Blvd. #200 telephone city, town Rockville state MD zip code 20852 4. Location of Legal Description courthouse, registry of deeds, etc. Montgomery County Judicial Center liber 29975 folio 776 city, town Rockville taxmapGR32 tax parcel P401 tax ID number 00144444 5. Primary Location of Additional Data . Contributing Resource in National Register District . Contributing Resource in Local Historic District Determined Eligible for the National Register/Maryland Register Determined Ineligible for the National Register/Maryland Register . Recorded by HABS/HAER Historic Structure Report or Research Report at MHT X Other: Peerless Rockville. Peerless Places 6. Classification Category Ownership Current Func tior i Resource Count district public agriculture landscape Contributing Noncontributing x buildina(s) x private X commerce/trade recreation/culture 1 buildinqs structure both defense religion sites site domestic social structures object education transportation objects funerary work in progress Total government unknown health care X vacant/not in use Number of Contributing Resources industry other: previously listed in the Inventory 7. Description Inventory No. M: 26-45 Condition excellent deteriorated good ruins X fair _ altered Prepare both a one paragraph summary and a comprehensive description of the resource and its various elements as it exists today. -

Development Activity and Disclosure Report

DEVELOPMENT ACTIVITY AND DISCLOSURE REPORT For the Quarter Ending September 30, 2008 Frederick County, Maryland Special Obligation Bonds (Urbana Community Development Authority) $30,000,000 Series 1998 $26,513,000 Series 2004A $6,461,000 Series 2004B Prepared by MUNICAP, INC. February 19, 2009 DEVELOPMENT ACTIVITY AND DISCLOSURE REPORT For the Quarter Ending September 30, 2008 I. UPDATED INFORMATION 1 II. INTRODUCTION 3 III. DEVELOPMENT ACTIVITY 6 A. Status of Governmental Permits 6 B. Status of Construction 11 C. Status of Sales 19 D. Status of Financing 24 IV. TRUSTEE ACCOUNTS 27 V. DISTRICT OPERATIONS 29 A. Levy of Special Taxes 29 B. Delinquent Special Taxes 34 C. Collection Efforts 35 VI. DISTRICT FINANCIAL INFORMATION 36 A. Bonds Outstanding and Reserve Fund 36 B. Property By Ownership and Classification 36 C. Special Taxes Paid By Owner and Classification 36 VII. SIGNIFICANT EVENTS 38 A. Developer Significant Events 38 B. Listed Events 38 I. UPDATED INFORMATION Information updated for the quarter ending September 30, 2008 is as follows: • The developer reports that construction of Phase One and Phase Two of Maryland Route 355 is complete. According to the developer, the project is expected to be submitted to the State Highway Administration in 2009. • As of September 30, 2008, Monocacy reports that there have been 527 settlements between builders and homebuyers in Villages X, XI and part of XIV (formerly X) in Section M7, compared to 526 during the second quarter of 2008. • As of September 30, 2008, Monocacy reports that there have been 160 settlements between builders and homebuyers in Village XII, compared to 158 during the second quarter of 2008. -

IN THIS ISSUE: Arlington, VA 22216 BULK RATE U.S

NEWSLETTER OF THE NATIONAL CAPITAL CHAPTER JAN/FEB 1984 dcr bavcrischc Box 685 IN THIS ISSUE: Arlington, VA 22216 BULK RATE U.S. POSTAGE PAID Winery Tour YNN30168*84*07*4 ARLINGTON, VA JOHN B. CARPENTER PERMIT#2314 Annual Election RURAL ROUTE 2 Rambling Ruminations BOX 607N Gray Market Update WHITE PLAINES, HO 20695 1984 Predictions AU1DSAL£S 770-6100 DATSUN — BMW — SAAB SALES — LEASING — SERVICE — PARTS "Much More" Service Program "Much More" Means Lower and Exact Pricing Before We Start Service While-U-Wait (in most cases) Appointments SAAB DATSUN ©II AJIOSALES 11605 Old Georgetown Rd., Rockville, Md. 20852 770-6100 '^ ^ master charge 1 AUTO REPAIR AUiU HtrtXIR ^^•^^v 2 COMING EVENTS TECH SESSION January 28, 1984 J & F Motors will host session on engine modifica tions — good or bad? Another topic is A/C units — rebuilding or replacing? J & F is at 4076 South Four Mile Run Drive in Arlington. Time: 9:30a — l:30p dcis the officiarl publicatio bayenschn of the National Capital Chapter of the BMWe Car Club of America, Inc. and is not in any way connected with the Bayerische Directions: From D.C. take 1-395 South to Glebe Motoren Werke AG or BMW of North America, Inc. It is provided by and Road/Shirlington, follow signs to Shirlington, turn right for the club membership only. All ideas, opinions and suggestions at the light onto Shirlington Road, then first left at South expressed in regard to technical or other matters are solely those of the Four Mile Run Drive, about 1.6 miles on your left. -

For the Record September 1998

For the Record September 1998 AMMENDALE NORMAL INSTITUTE OF The following is a list of MDE’s PEMCO CORPORATION - 5601 Eastern Avenue, PRINCE GEORGE’S COUNTY, INC. FR-132 - DELMARVA POWER & LIGHT - 10313 Old Ocean permitting activity from Baltimore, MD 21224. (TR 4902) Received an air 2535 Buckeystown Pike, Adamstown, MD 21710. City Boulevard, Crisfield, MD 21817. (99-OPT- permit to construct for one ball/pebble mill Sewage sludge application on agricultural land 3089) Oil operations permit for above ground storage July 15 - August 15, 1998 tank and transportation SOIL SAFE, INC. - 4600 Fayette Street, Baltimore, CANAM STEEL CORPORATION - 4010 Clay For more information MD 21224. (99-OPT-3472) Oil operations permit for Street, Point of Rocks, MD 21777-0285. (TR 4884) St. Mary’s County on any permits, above ground storage tank and transportation Received an air permit to construct for one foam spraying operation please call our THE PQ CORPORATION - 1301 East Fort Avenue, FORREST FARM WWTP - 23400 Block of Brown Environmental Permits Baltimore, MD 21230. (98-24-01665) Air quality EASTALCO ALUMINUM COMPANY - 5601 Road, Leonardtown, MD 20636. (99DP3280) permit to operate Manor Woods Road, Frederick, MD 21703. (TR Groundwater municipal discharge permit Service Center at 4885) Received an air permit to construct for one bin UNIVERSITY OF MD SCHOOL OF MEDICINE - vent for 400-ton storage silo H. W. MILLER AND SONS - 1905 Red Oak (410) 631-3772 10 South Pine Street, Baltimore, MD 21201. (98-24- Drive, Adelphi, MD 20783. (98-1112) Sewerage 00144) Air quality permit to operate FIL-TEC, INC. - 12129 Mapleville Road, Caveton, permit to construct sanitary sewers and a force main MD 21720. -

Transcript of Administrative Hearing

Transcript of Administrative Hearing Date: May 11, 2020 Case: Edmonson & Gallagher Property Services Planet Depos Phone: 888.433.3767 Email:: [email protected] www.planetdepos.com WORLDWIDE COURT REPORTING & LITIGATION TECHNOLOGY Transcript of Administrative Hearing 1 (1 to 4) Conducted on May 11, 2020 1 3 1 MONTGOMERY COUNTY 1 A P P E A R A N C E S 2 OFFICE OF ZONING AND ADMINISTRATIVE HEARINGS 2 ON BEHALF OF THE APPLICANT: 3 ------------------------------x 3 JODY S. KLINE, ESQUIRE 4 IN RE: : 4 MILLER, MILLER & CANBY 5 EDMONDSON & GALLAGHER PROPERTY: 5 200-B Monroe Street 6 SERVICES, LLC, application for: 6 Rockville, Maryland 20850 7 Milestone Senior Living : 7 (301)762-5212 8 Parcel 507, : 8 9 Middlebrook Subdivision : 9 ALSO PRESENT: 10 10 James Edmondson, The Applicant ------------------------------x 11 11 Jane Przygocki 12 Transcript of Proceedings 12 Michael A. Wiencek, Jr. 13 Conducted Virtually 13 Mahmut Agba 14 Monday, May 11, 2020 14 Daniel Park 15 9:28 a.m. EST 15 Nicole White 16 16 Jon S. Frey 17 17 Nana Johnson 18 Before: 18 19 LYNN A. ROBESON HANNAN, 19 20 Administrative Hearing Examiner 20 21 21 22 22 23 Job No.: 287912 23 24 Pages: 1 - 145 24 25 Reported by: Stephanie L. Hummon, RPR 25 2 4 1 Transcript of Proceedings in the 1 C O N T E N T S 2 above-captioned matter, conducted virtually. 2 EXAMINATION OF JAMES EDMONDSON PAGE 3 3 By Mr. Kline 9 4 4 EXAMINATION OF JANE PRZYGOCKI PAGE 5 5 By Mr. Kline 34 6 6 EXAMINATION OF MICHAEL A. -

Download This

NPS Form 10-900 OMB No. 10024-0018 (Oct. 1990) , United States Department of the Interior National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Registration Form This form is for use in nominating or requesting determinations for individual properties and districts. See instructions in How to Complete the National Register of Historic Places Registration Form (National Register Bulletin 16A). Complete each item by marking V in the appropriate box or by entering the information requested. If any item does not apply to the property being documented, enter "N/A" for "not applicable." For functions, architectural classification, materials, and areas of significance, enter only categories and subcategories from the instructions. Place additional entries and narrative items on continuation sheets (NPS Form 10-900a). Use a typewriter, word process, or computer, to complete all items. 1. Name of Property __ historic name Monocacy Battlefield (Additional Information)_______________________________ other names ____________________________________________________ 2. Location street & number 4871 Urbana Pike not for publication city or town Frederick __ 13 vicinity state MD code MD county Frederick code 021 zip code 21704 3. State/Federal Agency Certification As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act of 1966, as amended, I hereby certify that this D nomination D request for determination of eligibility meets the docurnentation standards for registering properties in the National Register of Historic Places and meets the procedural and professional rec luirements set forth in 36 CFR Part 60. In my opinion, the property D meets D does not meet the National Register criteria. 1 recommend :hat this property be considered significant S nationally D statewide D locally.