Metropolitan Battlefields: Urban Topography and the Weaponization of Governance in Baghdad

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

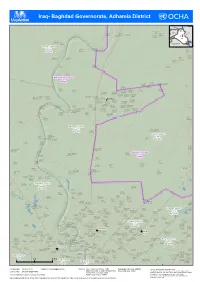

Iraq- Baghdad Governorate, Adhamia District

( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( ( Iraq- Baghdad Governorate, Adham( ia District ( ( Turkey Mosul! ! Albu Blai'a Erbil village Syria Ahmad al Al-Hajiyah IQ-P12429 Mahmud al Iran ( Mahmud River Al Bu Algah Khamis Baghdad Jadida Qaryat Albu IQ-P09040 IQ-P12203 IQ-P12398 IQ-P12326 Ramadi! ( IQ-P12308 ( ( Tannom ( !\ IQ-P12525 Jordan Najaf! Basrah! Hay Masqat Jurf Al IQ-P12295 Milah Bohroz Mahbubiyah ( SIaQ-uPd12i 2A(32rabia KIQu-wP1a2i3t22 ( IQ-P08417 ( ( ( Mohamed sakran Tarmia District IQ-P12335 Rashdiyah Muhammad (Noor village) Um Al al Jeb اﻟطﺎرﻣﯾﺔ IQ-P08355 Rumman IQ-P08339 ( ( IQ-P12386 IQ-D045 ( Al Halfayah village - 3 Mehdi al Ahmad Jamil Abdul Karim IQ-P12171 Hasan ( ( IQ-P09041 IQ-P08224 ( ( Al A`baseen IQ-P12332 ( village IQ-P12157 ( Sayyid Ahwiz Muhammad Musa Agha IQ-P08231 IQ-P08360 ( ( IQ-P12339 ( ( (( ( ( Fatah Chraiky IQ-P08312 IQ-P08307 ( ( ( Baghdad Governorate ( ( ﺑﻐداد IQ-G07 Qaryat Al Mohamad Khedidan 1 ( Khalaf Tameem Sakran IQ-P12318 ( ( ( Al-Mahmoud IQ-P12349 ( ( Al A'tb(a IQ-P12334 (( IQ-P12313 ( ( Qaryat ( village ( ( Darwesha IQ-P12161 ( Khalaf al IQ-P12359 ( ( Ulwan Muhammad Ja`atah Ali al Hajj ( Hussayniya - al `Abd al `Abbas IQ-P08333 Al Hussayniya IQ-P08297 Mahala 224 IQ-P12385 ( ( ( ( Al Hussainiya (Mahala 222) IQ-P12337 Al Husayniya ( IQ-P08330 ( ( ( - Mahalla 221 - Mahalla 213 IQ-P08264 ( IQ-P08243 IQ-P08251 Al Hussainiya Hussayniya - Al Hussayniya ( ( - Mahalla 216 Mahala 218 - Mahalla 220 IQ-P08253 ( IQ-P08329 IQ-P08261 ( Mahmud al Abdul Aziz Hay Al Waqf Al Hussainiya - ( ( Qal`at Jasim `Ulaywi Hamadi -

The Resurgence of Asa'ib Ahl Al-Haq

December 2012 Sam Wyer MIDDLE EAST SECURITY REPORT 7 THE RESURGENCE OF ASA’IB AHL AL-HAQ Photo Credit: Asa’ib Ahl al-Haq protest in Kadhimiya, Baghdad, September 2012. Photo posted on Twitter by Asa’ib Ahl al-Haq. All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. ©2012 by the Institute for the Study of War. Published in 2012 in the United States of America by the Institute for the Study of War. 1400 16th Street NW, Suite 515 Washington, DC 20036. http://www.understandingwar.org Sam Wyer MIDDLE EAST SECURITY REPORT 7 THE RESURGENCE OF ASA’IB AHL AL-HAQ ABOUT THE AUTHOR Sam Wyer is a Research Analyst at the Institute for the Study of War, where he focuses on Iraqi security and political matters. Prior to joining ISW, he worked as a Research Intern at AEI’s Critical Threats Project where he researched Iraqi Shi’a militia groups and Iranian proxy strategy. He holds a Bachelor’s Degree in Political Science from Middlebury College in Vermont and studied Arabic at Middlebury’s school in Alexandria, Egypt. ABOUT THE INSTITUTE The Institute for the Study of War (ISW) is a non-partisan, non-profit, public policy research organization. ISW advances an informed understanding of military affairs through reliable research, trusted analysis, and innovative education. ISW is committed to improving the nation’s ability to execute military operations and respond to emerging threats in order to achieve U.S. -

A New Formula in the Battle for Fallujah | the Washington Institute

MENU Policy Analysis / Articles & Op-Eds A New Formula in the Battle for Fallujah by Michael Knights May 25, 2016 Also available in Arabic ABOUT THE AUTHORS Michael Knights Michael Knights is the Boston-based Jill and Jay Bernstein Fellow of The Washington Institute, specializing in the military and security affairs of Iraq, Iran, and the Persian Gulf states. Articles & Testimony The campaign is Iraq's latest attempt to push militia and coalition forces into a single battlespace, and lessons from past efforts have seemingly improved their tactics. n May 22, the Iraqi government announced the opening of the long-awaited battle of Fallujah, the city only O 30 miles west of Baghdad that has been fully under the control of the Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant group for the past 29 months. Fallujah was a critical hub for al-Qaeda in Iraq and later ISIL in the decade before ISIL's January 2014 takeover. On the one hand it may seem surprising that Fallujah has not been liberated sooner -- after all, it has been the ISIL- controlled city closest to Baghdad for more than two years. The initial reason was that there was always something more urgent to do with Iraq's security forces. In January 2014, the Iraqi security forces were focused on preventing an ISIL takeover of Ramadi next door. The effort to retake Fallujah was judged to require detailed planning, and a hasty counterattack seemed like a pointless risk. In retrospect it may have been worth an early attempt to break up ISIL's control of the city while it was still incomplete. -

Rebooting U.S. Security Cooperation in Iraq

Rebooting U.S. Security Cooperation in Iraq MICHAEL KNIGHTS POLICY FOCUS 137 Rebooting U.S. Security Cooperation in Iraq MICHAEL KNIGHTS THE WASHINGTON INSTITUTE FOR NEAR EAST POLICY www.washingtoninstitute.org The opinions expressed in this Policy Focus are those of the author and not necessarily those of The Washington Institute, its Board of Trustees, or its Board of Advisors. All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America. No part of this publica- tion may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. © 2015 by The Washington Institute for Near East Policy The Washington Institute for Near East Policy 1828 L Street NW, Suite 1050 Washington, DC 20036 Design: 1000colors Photo: A Kurdish fighter keeps guard while overlooking positions of Islamic State mili- tants near Mosul, northern Iraq, August 2014. (REUTERS/Youssef Boudlal) CONTENTS Acknowledgments | v Acronyms | vi Executive Summary | viii 1 Introduction | 1 2 Federal Government Security Forces in Iraq | 6 3 Security Forces in Iraqi Kurdistan | 26 4 Optimizing U.S. Security Cooperation in Iraq | 39 5 Issues and Options for U.S. Policymakers | 48 About the Author | 74 TABLES 1 Effective Combat Manpower of Iraq Security Forces | 8 2 Assessment of ISF and Kurdish Forces as Security Cooperation Partners | 43 FIGURES 1 ISF Brigade Order of Battle, January 2015 | 10 2 Kurdish Brigade Order of Battle, January 2015 | 28 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS My thanks to a range of colleagues for their encouragement and assistance in the writing of this study. -

Hard Offensive Counterterrorism

Wright State University CORE Scholar Browse all Theses and Dissertations Theses and Dissertations 2019 The Use of Force: Hard Offensive Counterterrorism Daniel Thomas Wright State University Follow this and additional works at: https://corescholar.libraries.wright.edu/etd_all Part of the International Relations Commons Repository Citation Thomas, Daniel, "The Use of Force: Hard Offensive Counterterrorism" (2019). Browse all Theses and Dissertations. 2101. https://corescholar.libraries.wright.edu/etd_all/2101 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses and Dissertations at CORE Scholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in Browse all Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of CORE Scholar. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE USE OF FORCE: HARD OFFENSIVE COUNTERTERRORISM A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts By DANIEL THOMAS B.A., The Ohio State University, 2015 2019 Wright State University WRIGHT STATE UNIVERSITY GRADUATE SCHOOL Defense Date: 8/1/19 I HEREBY RECOMMEND THAT THE THESIS PREPARED UNDER MY SUPERVISION BY Daniel Thomas ENTITLED The Use of Force: Hard Offensive Counterterrorism BE ACCEPTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF Master of Arts. _______________________ Vaughn Shannon, Ph.D. Thesis Director ________________________ Laura M. Luehrmann, Ph.D. Director, Master of Arts Program in International and Comparative Politics Committee on Final Examination: ___________________________________ Vaughn Shannon, Ph.D. School of Public and International Affairs ___________________________________ Liam Anderson, Ph.D. School of Public and International Affairs ___________________________________ Pramod Kantha, Ph.D. School of Public and International Affairs ______________________________ Barry Milligan, Ph.D. -

How Soon Is Safe?

HOW SOON IS SAFE? IRAQI FORCE DEVELOPMENT AND ―CONDITIONS-BASED‖ US WITHDRAWALS Final Review Draft: February 5, 2009 Anthony H. Cordesman Arleigh A. Burke Chair in Strategy And Adam Mausner [email protected] [email protected] Cordesman: Iraqi Forces and US Withdrawals 4/22/09 Page ii The Authors would like to thank the men and women of the Multinational Force–Iraq and Multinational Security Transition Command - Iraq for their generous contribution to our work. The Authors would also like to thank David Kasten for his research assistance. Cordesman: Iraqi Forces and US Withdrawals 4/22/09 Page iii Executive Summary The US and Iraq now face a transition period that may well be as challenging as defeating Al Qa‘ida in Iraq, the other elements of the insurgency, and the threat from militias like the Mahdi Army. Iraq has made progress in political accommodation and in improving security. No one, however, can yet be certain that Iraq will achieve a enough political accommodation to deal with its remaining internal problems, whether there will be a new surge of civil violence, or whether Iraq will face problems with its neighbors. Iran seeks to expand its influence, and Turkey will not tolerate a sanctuary for hostile Kurdish movements like the PKK. Arab support for Iraq remains weak, and Iraq‘s Arab neighbors fear both Shi‘ite and Iranian dominance of Iraq as well as a ―Shi‘ite crescent‖ that includes Syria and Lebanon.. Much will depend on the capabilities of Iraqi security forces (ISF) and their ability to deal with internal conflicts and external pressures. -

Looking Into Iraq

Chaillot Paper July 2005 n°79 Looking into Iraq Martin van Bruinessen, Jean-François Daguzan, Andrzej Kapiszewski, Walter Posch and Álvaro de Vasconcelos Edited by Walter Posch cc79-cover.qxp 28/07/2005 15:27 Page 2 Chaillot Paper Chaillot n° 79 In January 2002 the Institute for Security Studies (ISS) beca- Looking into Iraq me an autonomous Paris-based agency of the European Union. Following an EU Council Joint Action of 20 July 2001, it is now an integral part of the new structures that will support the further development of the CFSP/ESDP. The Institute’s core mission is to provide analyses and recommendations that can be of use and relevance to the formulation of the European security and defence policy. In carrying out that mission, it also acts as an interface between European experts and decision-makers at all levels. Chaillot Papers are monographs on topical questions written either by a member of the ISS research team or by outside authors chosen and commissioned by the Institute. Early drafts are normally discussed at a semi- nar or study group of experts convened by the Institute and publication indicates that the paper is considered Edited by Walter Posch Edited by Walter by the ISS as a useful and authoritative contribution to the debate on CFSP/ESDP. Responsibility for the views expressed in them lies exclusively with authors. Chaillot Papers are also accessible via the Institute’s Website: www.iss-eu.org cc79-Text.qxp 28/07/2005 15:36 Page 1 Chaillot Paper July 2005 n°79 Looking into Iraq Martin van Bruinessen, Jean-François Daguzan, Andrzej Kapiszewski, Walter Posch and Álvaro de Vasconcelos Edited by Walter Posch Institute for Security Studies European Union Paris cc79-Text.qxp 28/07/2005 15:36 Page 2 Institute for Security Studies European Union 43 avenue du Président Wilson 75775 Paris cedex 16 tel.: +33 (0)1 56 89 19 30 fax: +33 (0)1 56 89 19 31 e-mail: [email protected] www.iss-eu.org Director: Nicole Gnesotto © EU Institute for Security Studies 2005. -

Japan's Official Development Assistance

Japan’s Official Development Assistance Japan pledged up to $ 5 billion of assistance for Technical reconstruction in Iraq Cooperation (Aimed at improving various skills) Madrid Conference (October 2003) Training FY 2003 - 2011 a total of about 5,000 Iraqi people participated Loan Assistance Grant Aid in training courses $ 3.5 billion $ 1.5 billion arranged by JICA in Japan or other countries. By JICA 15 projects Emergency assistance on Electricity, Oil, Water, basic infrastructures + Reconstruction in various Transportation, Irrigation, etc. Technical sectors + 4 new Cooperation Project 3 projects in the field of ⇒ beyond $ 4.1 billion + Agriculture in KRG & Japan pledged an 1 project in field of the additional $ 100 million Agriculture Irrigation in GOI Debt Reduction of grant aid. (2007) $ 6 billion JICA ODA Loan Projects in Iraq Water Supply Improvement Project in Kurdistan Region [JP¥ 34.3 bil / US$ 303 mil] Deralok Hydropower Plant Construction Project [[JP¥JP¥ 1 17.07.0 bil / US$ 165 mil] Electricity Sector Reconstruction Project in Kurdistan Region [ [JP¥JP¥ 14.7 bil / US$ 127 mil] Water Sector Loan Project in Midwestern Iraq [[JP¥JP¥ 41 41.3.3 bil / US$ 401 mil] Health Sector Reconstruction Project [[JP¥JP¥ 10.2 bil / US$ 126 mil] Irrigation Sector Loan [[JP¥JP¥ 9.5 bil bil// US$ 86 mil] AlAl-Akkaz-Akkaz Gas Power Plant Construction Project Electricity Sector Reconstruction Project [JP[JP¥¥ 29 29.6.6 bil / US$ 287 mil] JPJP¥¥ 32.6 bil bil// US$ 281 mil] ((BaijiBaiji Refinery Upgrading Project (E/S) Baghdad Sewerage Facilities -

A Tale of Two Cities the Use of Explosive Weapons in Basra and Fallujah, Iraq, 2003-4 Report by Jenna Corderoy and Robert Perkins

December 2014 A TALE OF TWO CITIES The use of explosive weapons in Basra and Fallujah, Iraq, 2003-4 Report by Jenna Corderoy and Robert Perkins Editor Iain Overton With thanks to Henry Dodd, Jane Hunter, Steve Smith and Iraq Body Count Copyright © Action on Armed Violence (December 2014) Cover Illustration A US Marine Corps M1A1 Abrams tank fires its main gun into a building in Fallujah during Operation Al Fajr/Phantom Fury, 10 December 2004, Lance Corporal James J. Vooris (UMSC) Infographic Sarah Leo Design and Printing Matt Bellamy Clarifications or corrections from interested parties are welcome Research and publications funded by the Government of Norway, Ministry of Foreign Affairs. A tale of two cities | 1 CONTENTS FOREWORD 2 IRAQ: A TIMELINE 3 INTRODUCTION: IRAQ AND EXPLOSIVE WEAPONS 4 INTERnatiONAL HumanitaRIAN LAW 6 AND RulES OF ENGAGEMENT BASRA, 2003 8 Rattling the Cage 8 Air strikes: Munition selection 11 FALLUJAH, 2004 14 Firepower for manpower 14 Counting the cost 17 THE AFTERmath AND LESSONS LEARNED 20 CONCLUSION 22 RECOMMENDatiONS 23 2 | Action on Armed Violence FOREWORD Sound military tactics employed in the pursuit of strategic objectives tend to restrict the use of explosive force in populated areas “ [... There are] ample examples from other international military operations that indicate that the excessive use of explosive force in populated areas can undermine both tactical and strategic objectives.” Bård Glad Pedersen, State Secretary, Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Norway, 17 June 20141 The language of conflict has changed enormously. their government is not the governing authority. Today engagements are often fought and justified Three case studies in three places most heavily- through a public mandate to protect civilians. -

Download Here

shiites under attack Author : Muhammad Jawad Chirri About the Author Introduction Do The Shiite Muslims Say That The Qur'an Is Incomplete? Do the Shi'ite Muslims Say That the Revelation Came to Muhammad byMistake, and That it Was Intended for Ali? Do the Imams Have Any Authority on the Universe? Did the Shiite Muslims Borrow Some Jewish Teachings? Was Ibn Saba the Organizer of the Revolt Against 'Uthman in Basra, Kufa, and Egypt? Did Muslims Other Than Shiites Borrow Religious Teachings from Jews? The Relationship Between Muslims and Jews in the Present Era Are The Shiites Negative Towards The Companions? Unity of the Muslims and the School of Ahl al‐Bayt Bibliography Presented by http://www.alhassanain.com & http://www.islamicblessings.com About the Author Imam Muhammad Jawad Chirri is Lebanese by birth and a graduate of the Islamic Institute of Najaf in Iraq. Before reaching the age of 25, he wrote about Islamic jurisprudence and its basis. The following are some of his books dealing with this subject: 1. Al‐Riyad in the Basis of Jurisprudence 2. Al‐Taharah (the purity) 3. Fasting 4. The Book of Prayer 5. The Islamic Wills When he returned from Najaf to Lebanon, Imam Chirri and the unforgettable personality, Sheikh Muhammad Jawad Mughniyya, the author of many valuable books, waged a campaign trying to awaken the people of southern Lebanon and urging them to rise in order to gain The linked image cannot be displayed. The file may have been moved, renamed, or deleted. Verify that the link points to the correct file and location. -

The Real Outcome of the Iraq War: US and Iranian Strategic Competition in Iraq

The Real Outcome of the Iraq War: US and Iranian Strategic Competition in Iraq By Anthony H. Cordesman, Peter Alsis, Adam Mausner, and Charles Loi Anthony H. Cordesman Arleigh A. Burke Chair in Strategy Revised: December 20, 2011 Note: This draft is being circulated for comments and suggestions. Please provide them to [email protected] Chapter 6: US Strategic Competition with Iran: Competition in Iraq 2 Executive Summary "Americans planted a tree in Iraq. They watered that tree, pruned it, and cared for it. Ask your American friends why they're leaving now before the tree bears fruit." --Mahmoud Ahmadinejad.1 Iraq has become a key focus of the strategic competition between the United States and Iran. The history of this competition has been shaped by the Iran-Iraq War (1980-1988), the 1991 Gulf War, and the US invasion of Iraq in 2003. Since the 2003 war, both the US and Iran have competed to shape the structure of Post-Saddam Iraq’s politics, governance, economics, and security. The US has gone to great lengths to counter Iranian influence in Iraq, including using its status as an occupying power and Iraq’s main source of aid, as well as through information operations and more traditional press statements highlighting Iranian meddling. However, containing Iranian influence, while important, is not America’s main goal in Iraq. It is rather to create a stable democratic Iraq that can defeat the remaining extremist and insurgent elements, defend against foreign threats, sustain an able civil society, and emerge as a stable power friendly to the US and its Gulf allies. -

Annual Report 2007 Annual Report Russia

UNITED STATES COMMISSION ON INTERNATIONAL RELIGIOUS FREEDOM Annual Report 2007 Annual Report RUSSIA UNITED STATES COMMISSION ON INTERNATIONAL RELIGIOUS FREEDOM Annual Report MAY 2007 U.S. Commission on International Religious Freedom 800 North Capitol Street, NW Suite 790 Washington, DC 20002 202-523-3240 202-523-5020 (fax) www.uscirf.gov UNITED STATES COMMISSION ON INTERNATIONAL RELIGIOUS FREEDOM Commissioners Chair Felice D. Gaer Vice Chairs Michael Cromartie Dr. Elizabeth H. Prodromou Nina Shea Dr. Khaled M. Abou El Fadl Preeta D. Bansal Archbishop Charles J. Chaput Dr. Richard D. Land Bishop Ricardo Ramirez John V. Hanford, III, ex officio, non-voting member Executive Director Joseph R. Crapa UNITED STATES COMMISSION ON INTERNATIONAL RELIGIOUS FREEDOM Staff Tad Stahnke, Deputy Director for Policy David Dettoni, Deputy Director for Outreach Judith Ingram, Director of Communications Holly Smithson, Director of Government Affairs Carmelita Hines, Director of Administration Patricia Carley, Associate Director for Policy Angela Stephens, Assistant Communications Director Dwight Bashir, Senior Policy Analyst Catherine Cosman, Senior Policy Analyst Deborah DuCre, Receptionist Scott Flipse, Senior Policy Analyst Julia Kirby, Middle East Researcher Mindy Larmore, East Asia Researcher Tiffany Lynch, Research Assistant Jacqueline A. Mitchell, Executive Assistant Allison Salyer, Legislative Assistant Stephen R. Snow, Senior Policy Analyst Christopher Swift, Researcher UNITED STATES COMMIssION ON INTERNATIONAL RELIGIOUS FREEDOM Washington, DC, May 1, 2007 The PRESIDENT The White House DEAR MR. PRESIDENT: On behalf of the United States Commission on International Religious Freedom, I am transmitting to you the annual report, prepared in compliance with section 202(a)(2) of the International Religious Freedom Act of 1998, 22 U.S.C.