Homogenization of Fish Faunas and Concurrent Anthropogenic Impacts on Plains Streams in Western Kansas: 1854–2003 Mark E

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Notropis Girardi) and Peppered Chub (Macrhybopsis Tetranema)

Arkansas River Shiner and Peppered Chub SSA, October 2018 Species Status Assessment Report for the Arkansas River Shiner (Notropis girardi) and Peppered Chub (Macrhybopsis tetranema) Arkansas River shiner (bottom left) and peppered chub (top right - two fish) (Photo credit U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service) Arkansas River Shiner and Peppered Chub SSA, October 2018 Version 1.0a October 2018 U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Region 2 Albuquerque, NM This document was prepared by Angela Anders, Jennifer Smith-Castro, Peter Burck (U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS) – Southwest Regional Office) Robert Allen, Debra Bills, Omar Bocanegra, Sean Edwards, Valerie Morgan (USFWS –Arlington, Texas Field Office), Ken Collins, Patricia Echo-Hawk, Daniel Fenner, Jonathan Fisher, Laurence Levesque, Jonna Polk (USFWS – Oklahoma Field Office), Stephen Davenport (USFWS – New Mexico Fish and Wildlife Conservation Office), Mark Horner, Susan Millsap (USFWS – New Mexico Field Office), Jonathan JaKa (USFWS – Headquarters), Jason Luginbill, and Vernon Tabor (Kansas Field Office). Suggested reference: U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. 2018. Species status assessment report for the Arkansas River shiner (Notropis girardi) and peppered chub (Macrhybopsis tetranema), version 1.0, with appendices. October 2018. Albuquerque, NM. 172 pp. Arkansas River Shiner and Peppered Chub SSA, October 2018 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ES.1 INTRODUCTION (CHAPTER 1) The Arkansas River shiner (Notropis girardi) and peppered chub (Macrhybopsis tetranema) are restricted primarily to the contiguous river segments of the South Canadian River basin spanning eastern New Mexico downstream to eastern Oklahoma (although the peppered chub is less widespread). Both species have experienced substantial declines in distribution and abundance due to habitat destruction and modification from stream dewatering or depletion from diversion of surface water and groundwater pumping, construction of impoundments, and water quality degradation. -

October 2002 Local/ Length Width Persons Damage Location Date Standard (Miles) (Yards) Killed Injured Property Crops Character of Storm

Time Path Path Number of Estimated October 2002 Local/ Length Width Persons Damage Location Date Standard (Miles) (Yards) Killed Injured Property Crops Character of Storm OKLAHOMA, Western, Central and Southeast Alfalfa County 2 S Cherokee02 1135CST 0 0 Thunderstorm Wind (G52) Grant County Pond Creek02 1730CST 0 0 Hail(0.75) Garfield County 1 W Kremlin02 1745CST 0 0 20K Thunderstorm Wind Severe straight-line winds downed several large tree limbs and blew a boat and trailer about 100 yards. In addition, several house windows were broken; a cattle feeder was blown onto a nearby road; numerous wooden fences were blown over, and the westward-facing wall of a storage shed was pushed in three to five inches. Kay County Ponca City02 1835CST 0 0 Hail(0.88) Hail was reported on the northwest side of the city. Alfalfa County 1 N Cherokee03 0000CST 0 0 60K Flash Flood Four homes received minor damage from high water. Two vehicles were pulled out of high water, and State Highway 8 was closed due to high water. Woodward County 2 SW Mutual03 0200CST 0 0 20K Flash Flood 0800CST A paved road was washed away. Alfalfa County 2 SE Helena03 0300CST 0 0 0 Flash Flood State Highway 45 was closed due to high water. OKZ005-007>008- Woods - Grant - Kay - Woodward - Major - Dewey - Blaine - Kingfisher 010>011-015-017>018 03 0700CST 0 0 25K Flood 06 1430CST Two days of periodic heavy rain fell across much of northwest Oklahoma with some areas receiving nearly seven inches. Large amounts of runoff caused many rivers to rise above flood stage, including the Salt Fork Arkansas River at Tonkawa, the Chikaskia River near Braman and Blackwell, the Cimarron River near Waynoka, Okeene, and Dover, and the North Canadian River near Seiling. -

Drought of Water Year 2006 Compared with Four Major Drought Periods of the 20Th Century in Oklahoma

Prepared in cooperation with the Oklahoma Water Resources Board Hydrologic Drought of Water Year 2006 Compared with Four Major Drought Periods of the 20th Century in Oklahoma • .... Canadian River near Norman February 1952 -,. Canadian River downstream from State Highway. 99" or' near Ada August 16, 2006.. Scientific Investigations Report 2008-5199 U.S. Department of the Interior U.S. Geological Survey Front Cover: Picture One shows wind ripples and river silts, Canadian River near Norman, Cleveland County, Okla- homa, taken February 1952. Photographer: W.B. Hamilton, from U.S. Geological Survey Photographic Library. Picture Two shows the dry Canadian River near Ada, Pontotoc County, Oklahoma, downstream from State High- way 99, taken August 16, 2006. Photographer: Daniel Fenner, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. Hydrologic Drought of Water Year 2006 Compared with Four Major Drought Periods Of the 20th Century in Oklahoma By Robert L. Tortorelli Prepared in cooperation with the Oklahoma Water Resources Board Scientific Investigations Report 2008–5199 U.S. Department of the Interior U.S. Geological Survey U.S. Department of the Interior DIRK KEMPTHORNE, Secretary U.S. Geological Survey Mark D. Myers, Director U.S. Geological Survey, Reston, Virginia: 2008 This and other USGS information products are available at: http://store.usgs.gov/ U.S. Geological Survey Box 25286, Denver Federal Center Denver, CO 80225 To learn about the USGS and its information products visit http://www.usgs.gov/ 1-888-ASK-USGS Any use of trade, product, or firm names is for descriptive purposes only and does not imply endorsement by the U.S. Government. -

Oklahoma Geological Survey Open-File Report Disclaimer

Oklahoma Geological Survey Open-File Report Disclaimer Open-File Reports are used for the dissemination of information that fills a public need and are intended to make the results of research available at the earliest possible date. Because of their nature and possibility of being superseded, an Open-File Report is intended as a preliminary report not as a final publication. Analyses presented in this article are based on information available to the author, and do not necessarily represent the views of the Oklahoma Geological Survey, the University of Oklahoma, their employees, or the State of Oklahoma. The accuracy of the information contained herein is not guaranteed and any mention of trade names are not an endorsement by the author, the Oklahoma Geological Survey, or the University of Oklahoma. The Oklahoma Geological Survey is a state agency for research and public service, mandated in the State Constitution to study Oklahoma’s land, water, mineral and energy resources and to promote wise use and sound environmental practices. Preface This report is updated from one that was originally prepared for the Tulsa District Office of the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers (USACE) in 1978 to characterize the geology at and near major natural salt plains in parts of the Arkansas River Chloride Control Project (ARCCP) area in northwestern Oklahoma. The ARCCP is designed to control natural chloride-brine emissions at major source areas in northwestern Oklahoma, and thus to improve water quality for municipal, industrial, and agricultural use downstream from the salt plains. Improvements that may help control brine emissions include construction of low-flow dams, pump stations, and diversion pipelines to impoundment facilities. -

Index of Surface-Water Records to September 30, 1955

GEOLOGICAL SURVEY CIRCULAR 387 INDEX OF SURFACE-WATER RECORDS TO SEPTEMBER 30, 1955 PART 7.-LOWER MISSISSIPPI RIVER BASIN PftDPE1n'Y cnr U. 5. GtO ! :-:cn:Al~ SURVEY. PUBLIC ;;::..'·,:: :Cri OFFIC~ SAN nM,l-4Ci:,.;;.;o, Ci\Ltf"O~NIA UNITED STATES DEPAR'l'MENT OF THE INTERIOR Fred A. Seaton, Secretary GEOLOGICAL SURVEY Thomas B. Nolan, Director GEOLOGICAL SURVEY CIRCULAR 387 INDEX OF SURFACE-WATER RECORDS TO SEPTEMBER 30,1955 PART 7.-LOWER MISSISSIPPI RIVER BASIN By J. S. Gatewood Washington, D. C., 1956 Free on application to the Geological Survey, Washington 25, D. C. INDEX OF SURFACE-WATER RECORDS TO SEPTEMBER 30,1955 PART 7.-LOWER MISSISSIPPI RIVER BASIN By J. S. Gatewood EXPLANATION This index lists th~ streamflow and reservoir stations in the Lower Mississippi River basin for which records have been or are to be published in reports of the Geological Survey for periods prior to September 30, 1955. Periods of record for the same station published by other agencies are listed only when they contain more detailed information or are for periods not reported in publications of the Geological Survey. The stations are listed in the downstream order first adopted for use in the 1951 series of water-supply papers on surface-water supply of the United States. Starting at the headwater of each stream all stations are listed in a downstream direction. Tributary streams are indicated by indention and are inserted between main-stem stations in the order in which they enter the main stream. To indicate the rank of any tributary on which a record is available and the stream to which it is immediately tributary, each indention in the listing of stations represents one rank. -

RIVERS, STREAMS, and LAKES of OKLAHOMA Kenneth S

Page 12, Rivers, Streams, and Lakes EDUCATIONAL PUBLICATION 9: 2008 EXPLANATION Scenic River; number corresponds to name in text Salt Plain; number corresponds to name in text Table 4. Major lakes and reservoirs in Oklahoma Lake Area Drainage Areaa Capacity Location Normal Pool Normal Pool (acres) (square miles) (acre-feet) County/Counties Eufaula 105,500 47,522 2,314,600 McIntosh; Pittsburg; Haskell Texoma 88,000 39,719 2,643,300 Love; Marshall; Bryan; Johnston Grand Lake O’ the 46,500 10,298 1,672,000 Delaware; Ottawa; Mayes Cherokees Robert S. Kerr 43,800 147,756 525,700 Haskell; Sequoyah; Le Flore Oologah 29,460 4,339 553,400 Rogers; Nowata Keystone 23,610 74,506 557,600 Osage; Pawnee; Creek; Tulsa Fort Gibson 19,900 12,492 365,200 Wagoner; Cherokee; Mayes Kaw 17,040 46,530 428,600 Kay; Osage Broken Bow 14,200 754 918,070 McCurtain Sardis 13,610 275 274,330 Pushmataha; Latimer Hugo 13,250 1,709 157,600 Choctaw Tenkiller 12,900 1,610 654,100 Cherokee; Sequoyah Webbers Falls 11,600 97,033 170,100 Muskogee Hudson 10,900 11,533 220,300 Mayes Skiatook 10,190 354 322,700 Osage Waurika 10,100 562 203,100 Jefferson; Stephens; Cotton Foss 8,880 1,496 256,220 Custer Great Salt Plains 8,690 3,200 31,420 Alfalfa Canton 7,910 12,483 111,310 Blaine; Dewey Wister 7,333 993 62,360 Le Flore aData from the Oklahoma Water Resources Board (1990). RIVERS, STREAMS, AND LAKES OF OKLAHOMA Kenneth S. -

Summary of Annual Records of Chemical Quality of Water of the Arkansas River in Oklahoma and Arkansas 1945-52

GEOLOGICAL SURVEY CIRCULAR 361 SUMMARY OF ANNUAL RECORDS OF CHEMICAL QUALITY OF WATER OF THE ARKANSAS RIVER IN OKLAHOMA AND ARKANSAS 1945-52 Prepared in cooperation with the University of Arkansas Engineering Experiment Station, Oklahoma Planning and Resources Board, Division of Water Resources, and the Oklahoma Agricultural and Mechanical College, Division of Engineering Research. UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR Douglas McKay, Secretary GEOLOGICAL SURVEY W. E. Wrather, Director GEOLOGICAL SURVEY CIRCULAR 361 SUMMARY OF ANNUAL RECORDS OF CHEMICAL QUALITY OF WATER OF THE ARKANSAS RIVER IN OKLAHOMA AND ARKANSAS, 1945-52 By T. B. Dover and J. W. Geurin A PROGRESS REPORT Prepared in cooperation with the University of Arkansas Engineering Experiment Station, Oklahoma Planning and Resources Board, Division of Water Resources, and the Oklahoma Agricultural and Mechanical College, Division of Engineering Research Washington, D. C.,1955 Free on application to the Geological Survey, Washington 25, D. C. SUMMARY OF ANNUAL RECORDS OF CHEMICAL QUALITY OF WATER OF THE ARKANSAS RIVER IN OKLAHOMA AND ARKANSAS, 1945-52 A PROGRESS REPORT By T. B. Dover and J. W. Geurin CONTENTS Page Page Abstract.................................... 1 Chemical quality Continued Introduction............................... 4 Collection and examination of samples... Purpose and scope of report...... 4 Oklahoma-Kansas State line to Tulsa..... 14 Personnel and acknowledgments. 4 Influence of Salt Fork Arkansas River. 14 Arkansas River drainage basin...... 4 Influence of Cimarron River.............. 14 Location and extent.................. 4 Tulsa to Van Buren............................. 17 Physical and geologic features... 5 Influence of Verdigris, Neosho, and Oklahoma............................ 5 Illinois Rivers............................. 17 Arkansas............................. 5 Influence of Canadian River....... ....... 18 C lima te................................ -

Downstream Effects of Dams on Alluvial Rivers

Downstream Effects of Downstream Effects of Dams on Alluvial Rivers By GARNETT P. WILLIAMS and M. GORDON WOLMAN GEOLOGICAL SURVEY PROFESSIONAL PAPER 1286 UNITED STATES GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE, WASHINGTON : 1984 UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR WILLIAM P. CLARK, Secretary GEOLOGICAL SURVEY Dallas L. Peck, Director First printing 1984 Second printing 1985 Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data Williams, Garnett P. Downstream effects of dams on alluvial rivers. (Geological Survey Professional Paper; 1286) Includes bibliographical references. Supt. of Docs. No.: I 19.16:1286 1. River channels. 2. Rivers Regulation. 3. Dams. I. Wolman, M. Gordon (Markley Gordon), 1924- II. Title. III. Title: Alluvial rivers. IV. Series. TC175.W48 1983 551.48'2 82-600318 For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office Washington, D.C. 20402 CONTENTS Page Page Abstract ......................... 1 Downstream effects of dams continued Introduction ....................... 1 Mean bed elevation Continued Scope of study ................... 1 Longitudinal-profile changes ............. 26 Study sites and selection criteria ......... 1 Bed material and degradation ................ 29 Acknowledgments .................. 2 Theoretical expectations ................. 29 Methods of analysis and data sources ......... 2 Variations in bed-material sizes with time at a cross sec Water discharge .................. 2 tion ........................... 29 Sediment load .................... 2 Variations in bed-material sizes with -

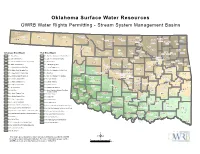

OWRB Stream System Management

Oklahoma Surface Water Resources OWRB Water Rights Permitting - Stream System Management Basins 2-9-4 Boise City Texas Beaver Harper Buffalo Newkirk Nowata Miami Cimarron Alva Grant Washington Guymon Kay 2-5-4 Cherokee Medford 2-9-3 2-10-1 2-14 Bartlesville Ottawa Beaver 2-10-2 Craig Woods Ponca City 2-15-2 Pawhuska Nowata Alfalfa 2-12 Vinita Osage Woodward Jay 2-5-3 Enid Noble Pawnee 2-13 2-16 Woodward Pawnee Rogers Major Pryor Arkansas River Basin Red River Basin Fairview Garfield Perry Delaware Ellis Owasso Claremore Mayes 2-1, Poteau River 1-1, Red River Mainstem (To Kiamichi River) Arnett 2-11 Sand Springs Dewey 2-9-2 Stillwater 2-2, Lower Arkansas River 1-2, Little River (McCurtain County) Taloga Tulsa 2-15-1 2-9-1 Broken Arrow Adair Payne Sapulpa Cherokee 2-3, Lower Canadian River (To Lake Eufaula) 1-3, Kiamichi River Wagoner Kingfisher Tahlequah 2-6-3 Guthrie Wagoner 2-4, Middle Arkansas River 1-4-1, Muddy Boggy River Blaine Kingfisher 2-4 Tulsa 2-17 Stilwell Watonga Creek Roger Mills Logan 2-5-1, Lower North Canadian River 1-4-2, Clear Boggy Creek Muskogee Chandler 2-5-2, Middle North Canadian River 1-5, Red River Mainstem (To Blue River) 2-5-2 Canadian Edmond 1-8-4 Custer 2-7 Okmulgee Muskogee Cheyenne Arapaho Oklahoma 2-5-3, Upper North Canadian River 1-6, Blue River Weatherford El Reno Yukon Bethany Lincoln Okfuskee Sequoyah Oklahoma City Okmulgee Elk City Del City Sallisaw 2-5-4, North Canadian Headwaters 1-7, Red River Mainstem (To Washita) Okemah Midwest City Washita Mustang 2-6-1, Lower Canadian River 1-8-1, Lower Washita -

KOARC 2017 Engg Comm

KANSAS-OKLAHOMA ARKANSAS RIVER COMPACT COMMISSION ENGINEERING COMMITTEE REPORT July 28, 2021 Oklahoma Water Resources Board Oklahoma City, OK This report covers water year (WY) 2020: October 1, 2019 through September 30, 2020. The report contains the standard updates to streamflow data, water quality data and reservoir conservation storage capacities constructed in the Compact area. WY2020 mean flows at four of the five Oklahoma gaging stations were lower than WY2019 mean flows. At the Cimarron River gage near Waynoka, OK, the WY2020 mean flow was 115 cfs, an 81% decrease from the WY2019 mean flow of 607 cfs. Three of the other Oklahoma gaging stations reported decreases in mean flow ranging from 42% to 70% between WY2019 and WY2020. Due to a bridge reconstruction project, the fifth Oklahoma gaging station – the Chikaskia River gage near Blackwell, OK – was not in operation from April 2, 2020 through the end of the water year. The Verdigris River gage at Independence, KS reported a 51% decrease in mean flow, from 6,302 cfs in WY2019 to 3,080 cfs in WY2020. The Arkansas River gage at Arkansas City, KS reported a 76% decrease in mean flow, from 6,962 cfs in WY2019 to 1,655 cfs in WY2020. WY2020 mean flows at the gaging stations in Kansas and Oklahoma varied in relation to the historical mean flows at those gaging stations, ranging from a 57% decrease at the Cimarron River gage near Waynoka, OK to a 36% increase at the Verdigris River gage near Independence, KS. The Engineering Committee reports that there were no new water storage structures completed in the Kansas or Oklahoma Compact areas between October 1, 2019 and September 30, 2020 that exceeded the 100-acre-foot conservation storage minimum requirement as set forth in the Compact. -

Robert Edward Pearce Date of Degree: May 23, 1965

Name: Robert Edward Pearce Date of Degree: May 23, 1965 Institution: Oklahoma State University Location: Stillwater, Oklahoma Title of Study: ·western Distribution of Platanus occidentalis L. in Oklahoma Pages in Study: 42 Candidate for Degree of Master of Natural Science Major Field: Natural Science. Scope and Method of Study: Determine the Western Distribution of Platanus occidentalis L. in Oklahoma. This was accomplished by making trips into Love, Carter, Murray, Garvin, McClain, Cleveland, Pontotoc, Seminole, Pottawatomine, Lincol;tn, Logan, Payne, Pawnee, Kay, and Grant Counties. Collections were made to verify the location. A distribution map of plant collected and they are on deposit in the Bebb Herbarium of the University of Oklahoma. A study was made of the unpublished Paper of the Ecology of the Bottomland of Oklahoma by Rice (1962). Findings and Conclusions: P. occidentalis L. are found along most of the creeks and rivers in the eastern half of the counties above. More abundant growth is along larger and wider creeks and rivers in the counties mentioned. P. ocd.dentalis L. are found growing with other species of trees. Few young trees were found in the narrow creeks. More trees were growing on limestone soils. ~ occidentalis L. are found to be more abundant to the east of the distri bution found in this paper. Adviser's Approval: WESTERN DISTRIBUTION OF PLATANUS OCCIDENTALIS L. IN OKLAHOMA By ROBERT EDWARD PEARCE Bachelor of Science Oklahoma State University Stillwater, Oklahoma 1954 Submitted to the faculty of the Graduate School of the Oklahoma State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF NATURAL SCIENCE May, 1965 THE WESTERN DISTRIBUTION OF THE PLATANUS OCCIDENTALIS 1. -

American Indian Tribal Census Tract Outline

37.038081N AMERICAN INDIAN TRIBAL CENSUS TRACT OUTLINE MAP (CENSUS 2000) 37.038081N 97.103404W 96.532548W LEGEND Arkansas River Arkansas River SYMBOL NAME STYLE INTERNATIONAL AIR (FEDERAL) Trust Land OTSA / TDSA AMERICAN INDIAN TRIBAL SUBDIVISION AIR (State) KANSAS 20 COWLEY 035 COWLEY 035 KANSAS 20 SDAISA OKLAHOMA 40 KAY 071 OSAGE 113 OKLAHOMA 40 Place within Subject Entity Incorporated Place / CDP Place outside of Subject Entity Incorporated Place / CDP Tribal Census Tract 1 ABBREVIATION REFERENCE: AIR = American Indian Reservation; Trust Land = Off−Reservation Trust Land; OTSA = Oklahoma Tribal; Statistical Area; TDSA = Tribal Designated Statistical Area; SDAISA = State Designated American Indian Statistical Area; CDP = Census Designated Place Grainola 30750 Military Inset Out Area 1 This map shows tribal census tract boundaries and numbers. A tribal census tract is a type of census tract defined within a federally recognized American Indian reservation or off−reservation trust land for the purpose of providing data based on an American Indiani hierarchy rather than by state and county. Newkirk 51300 Foraker 26750 Kaw Rsvr Beaver Creek KAW OTSA (5690) 108 Kildare Webb 39800 Kaw Lake City 79600 OSAGE RES (2595) Shidler 67200 Kaw City 38800 KAY 0 7 1 AGE OS 1 13 KAW−PONCA JOTA (5950) West Lake Ponca Kaw Rsvr Ponca City 59850 East Lake Ponca Burbank 09950 Ponca City 59850 McCord 44925 105 PONCA OTSA (5800) Salt Fork Arkansas River Fairfax City Lake Sheet Location within Entity Arkansas River Key to Adjacent Sheets 12 KAY 071 34 NOBLE 103 Salt Fork Arkansas River 3 SAGE 11 O SHEET 1 OF 4 PARENT SHEETS Salt Fork Arkansas River 3 NOBLE 10 Fairfax 24850 TOTAL SHEETS: 5 (Index 1; Parent 4; Inset 0) 36.580060N 36.580060N 97.103404W 96.532548W N ENTITY TYPE: American Indian Reservation 3 2 1 0 3 mi W E NAME: Osage Reservation (2595) ST: Oklahoma 6 5 4 3 2 1 S 0 6 km All legal boundaries and names are as of January 1, 2000.