Saving Italy 3PP

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Last Supper Seen Six Ways by Louis Inturrisi the New York Times, March 23, 1997

1 Andrea del Castagno’s Last Supper, in a former convent refectory that is now a museum. The Last Supper Seen Six Ways By Louis Inturrisi The New York Times, March 23, 1997 When I was 9 years old, I painted the Last Supper. I did it on the dining room table at our home in Connecticut on Saturday afternoon while my mother ironed clothes and hummed along with the Texaco. Metropolitan Operative radio broadcast. It took me three months to paint the Last Supper, but when I finished and hung it on my mother's bedroom wall, she assured me .it looked just like Leonardo da Vinci's painting. It was supposed to. You can't go very wrong with a paint-by-numbers picture, and even though I didn't always stay within the lines and sometimes got the colors wrong, the experience left me with a profound respect for Leonardo's achievement and a lingering attachment to the genre. So last year, when the Florence Tourist Bureau published a list of frescoes of the Last Supper that are open to the public, I was immediately on their track. I had seen several of them, but never in sequence. During the Middle Ages the ultima cena—the final supper Christ shared with His disciples before His arrest and crucifixion—was part of any fresco cycle that told His life story. But in the 15th century the Last Supper began to appear independently, especially in the refectories, or dining halls, of the convents and monasteries of the religious orders founded during the Middle Ages. -

Illustrations Ij

Mack_Ftmat.qxd 1/17/2005 12:23 PM Page xiii Illustrations ij Fig. 1. Expulsion of Adam and Eve from Paradise, ca. 1015, Doors of St. Michael’s, Hildesheim, Germany. Fig. 2. Masaccio, Expulsion of Adam and Eve from Paradise, ca. 1425, Brancacci Chapel, Church of Santa Maria del Carmine, Flo- rence. Fig. 3. Bernardo Rossellino, Facade of the Pienza Cathedral, 1459–63. Fig. 4. Bernardo Rossellino, Interior of the Pienza Cathedral, 1459–63. Fig. 5. Leonardo da Vinci, The Last Supper, 1495–98, Refectory of the Monastery of Santa Maria delle Grazie, Milan. Fig. 6. Anonymous Pisan artist, Pisa Cross #15, late twelfth century, Museo Civico, Pisa. Fig. 7. Anonymous artist, Cross of San Damiano, late twelfth century, Basilica of Santa Chiara, Assisi. Fig. 8. Giotto di Bondone, Cruci‹xion, ca. 1305, Arena (Scrovegni) Chapel, Padua. Fig. 9. Masaccio, Trinity Fresco, ca. 1427, Church of Santa Maria Novella, Florence. Fig. 10. Bonaventura Berlinghieri, Altarpiece of St. Francis, 1235, Church of San Francesco, Pescia. Fig. 11. St. Francis Master, St. Francis Preaching to the Birds, early four- teenth century, Upper Church of San Francesco, Assisi. Fig. 12. Anonymous Florentine artist, Detail of the Misericordia Fresco from the Loggia del Bigallo, 1352, Council Chamber, Misericor- dia Palace, Florence. Fig. 13. Florentine artist (Francesco Rosselli?), “Della Catena” View of Mack_Ftmat.qxd 1/17/2005 12:23 PM Page xiv ILLUSTRATIONS Florence, 1470s, Kupferstichkabinett, Staatliche Museen zu Berlin. Fig. 14. Present-day view of Florence from the Costa San Giorgio. Fig. 15. Nicola Pisano, Nativity Panel, 1260, Baptistery Pulpit, Baptis- tery, Pisa. Fig. -

The Scientific Narrative of Leonardoâ•Žs Last Supper

Best Integrated Writing Volume 5 Article 4 2018 The Scientific Narrative of Leonardo’s Last Supper Amanda Grieve Wright State University Follow this and additional works at: https://corescholar.libraries.wright.edu/biw Part of the Ancient, Medieval, Renaissance and Baroque Art and Architecture Commons, Classical Archaeology and Art History Commons, and the International and Area Studies Commons Recommended Citation Grieve, A. (2018). The Scientific Narrative of Leonardo’s Last Supper, Best Integrated Writing, 5. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by CORE Scholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in Best Integrated Writing by an authorized editor of CORE Scholar. For more information, please contact library- [email protected]. AMANDA GRIEVE ART 3130 The Scientific Narrative of Leonardo’s Last Supper AMANDA GRIEVE ART 3130: Leonardo da Vinci, Fall 2017 Nominated by: Dr. Caroline Hillard Amanda Grieve is a senior at Wright State University and is pursuing a BFA with a focus on Studio Painting. She received her Associates degree in Visual Communications from Sinclair Community College in 2007. Amanda notes: I knew Leonardo was an incredible artist, but what became obvious after researching and learning more about the man himself, is that he was a great thinker and intellectual. I believe those aspects of his personality greatly influenced his art and, in large part, made his work revolutionary for his time. Dr. Hillard notes: This paper presents a clear and original thesis about Leonardo da Vinci’s Last Supper that incorporates important scholarly research and Leonardo’s own writings. The literature on Leonardo is extensive, yet the author has identified key studies and distilled their essential contributions with ease. -

The Extraordinary Imagery of Andrea Del Castagno's Vision of St. Jerome Has Never Been Completely Explained. Painted for the C

A NEW SOURCE FOR ANDREA DEL CASTAGNO’S VISION OF ST. JEROME* ADRIENNE DEANGELIS The extraordinary imagery of Andrea del Castagno’s Vision of St. Jerome has never been completely explained. Painted for the chapel of Girolamo Corboli in Santissima Annunziata in Florence, the fresco altarpiece is traditionally dated to about 1454–1455. The saint, nearly nude in his torn gown, stands with one hand clutching the bloody stone with which he has been beating his breast in an act of penitence. His arms flung wide from his body, he seems to have been stopped in his act of self-flagellation by the vision above his head: a severely foreshortened crucified Christ supported by God the Father, under whose chin floats the dove of the Holy Spirit. The members of the Trinity shown in this manner form the Gnadenstuhl, the Throne of Mercy.1 Even the lion beside him seems to share in St. Jerome’s experience. Its head thrown back at the same angle, its mouth is opened in an outcry that in its animalistic response suggests less an understanding of the vision above than a reflexive imitation of its master’s transported state.2 Flanking the saint are two heavily draped female figures who also look up at this extraordinary depiction of the Trinity. The expression of St. Jerome and the placement of the Gnadenstuhl as emerging from behind his head, as if out of the sky and into the viewer’s worldly space, implies that St. Jerome’s penitential self-flagellation has been so compelling that he has re-evoked his desert experiences of the Trinity for them to see. -

NGA | 2012 Annual Report

NA TIO NAL G AL LER Y O F A R T 2012 ANNUAL REPort 1 ART & EDUCATION Diana Bracco BOARD OF TRUSTEES COMMITTEE Vincent J. Buonanno (as of 30 September 2012) Victoria P. Sant W. Russell G. Byers Jr. Chairman Calvin Cafritz Earl A. Powell III Leo A. Daly III Frederick W. Beinecke Barney A. Ebsworth Mitchell P. Rales Gregory W. Fazakerley Sharon P. Rockefeller Doris Fisher John Wilmerding Juliet C. Folger Marina Kellen French FINANCE COMMITTEE Morton Funger Mitchell P. Rales Lenore Greenberg Chairman Frederic C. Hamilton Timothy F. Geithner Richard C. Hedreen Secretary of the Treasury Teresa Heinz Frederick W. Beinecke John Wilmerding Victoria P. Sant Helen Henderson Sharon P. Rockefeller Chairman President Benjamin R. Jacobs Victoria P. Sant Sheila C. Johnson John Wilmerding Betsy K. Karel Linda H. Kaufman AUDIT COMMITTEE Robert L. Kirk Frederick W. Beinecke Leonard A. Lauder Chairman LaSalle D. Leffall Jr. Timothy F. Geithner Secretary of the Treasury Edward J. Mathias Mitchell P. Rales Diane A. Nixon John G. Pappajohn Sharon P. Rockefeller Frederick W. Beinecke Mitchell P. Rales Victoria P. Sant Sally E. Pingree John Wilmerding Diana C. Prince Robert M. Rosenthal TRUSTEES EMERITI Roger W. Sant Robert F. Erburu Andrew M. Saul John C. Fontaine Thomas A. Saunders III Julian Ganz, Jr. Fern M. Schad Alexander M. Laughlin Albert H. Small David O. Maxwell Michelle Smith Ruth Carter Stevenson Benjamin F. Stapleton Luther M. Stovall Sharon P. Rockefeller John G. Roberts Jr. EXECUTIVE OFFICERS Ladislaus von Hoffmann Chief Justice of the Diana Walker United States Victoria P. Sant President Alice L. -

Renaissance Florence – Instructor Andrea Ciccarelli T, W, Th 11:10-1:15PM (Time of Class May Change According to Museum/Sites Visit Times

M234 Renaissance Florence – Instructor Andrea Ciccarelli T, W, Th 11:10-1:15PM (Time of class may change according to museum/sites visit times. Time changes will be sent via email but also announced in class the day before). This course is designed to explore the main aspects of Renaissance civilization, with a major emphasis on the artistic developments, in Florence (1300’s – 1500’s). We will focus on: • The passage from Gothic Architecture to the new style that recovers ancient classical forms (gives birth again = renaissance) through Brunelleschi’s and Alberti’s ideas • The development of mural and table painting from Giotto to Masaccio, and henceforth to Fra Angelico, Ghirlandaio, Botticelli and Raphael • Sculpture, mostly on Ghiberti, Donatello and Michelangelo. We will study and discuss, of course, other great Renaissance artists, in particular, for architecture: Michelozzo; for sculpture: Desiderio da Settignano, Cellini and Giambologna; for painting: Filippo Lippi, Andrea del Castagno, Filippino Lippi, Bronzino and Pontormo. For pedagogical matters as well as for time constraints, during museum and church/sites visits we will focus solely or mostly on artists and works inserted in the syllabus. Students are encouraged to visit the entire museums or sites, naturally. Some lessons will be part discussion of the reading/ visual assignments and part visits; others will be mostly visits (but there will be time for discussion and questions during and after visits). Because of their artistic variety and their chronological span, some of the sites require more than one visit. Due to the nature of the course, mostly taught in place, the active and careful participation of the students is highly required. -

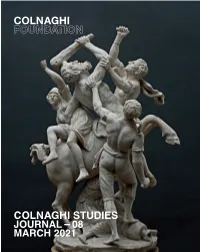

Journal 08 March 2021 Editorial Committee

JOURNAL 08 MARCH 2021 EDITORIAL COMMITTEE Stijn Alsteens International Head of Old Master Drawings, Patrick Lenaghan Curator of Prints and Photographs, The Hispanic Society of America, Christie’s. New York. Jaynie Anderson Professor Emeritus in Art History, The Patrice Marandel Former Chief Curator/Department Head of European Painting and JOURNAL 08 University of Melbourne. Sculpture, Los Angeles County Museum of Art. Charles Avery Art Historian specializing in European Jennifer Montagu Art Historian specializing in Italian Baroque. Sculpture, particularly Italian, French and English. Scott Nethersole Senior Lecturer in Italian Renaissance Art, The Courtauld Institute of Art, London. Andrea Bacchi Director, Federico Zeri Foundation, Bologna. Larry Nichols William Hutton Senior Curator, European and American Painting and Colnaghi Studies Journal is produced biannually by the Colnaghi Foundation. Its purpose is to publish texts on significant Colin Bailey Director, Morgan Library and Museum, New York. Sculpture before 1900, Toledo Museum of Art, Ohio. pre-twentieth-century artworks in the European tradition that have recently come to light or about which new research is Piers Baker-Bates Visiting Honorary Associate in Art History, Tom Nickson Senior Lecturer in Medieval Art and Architecture, Courtauld Institute of Art, underway, as well as on the history of their collection. Texts about artworks should place them within the broader context The Open University. London. of the artist’s oeuvre, provide visual analysis and comparative images. Francesca Baldassari Professor, Università degli Studi di Padova. Gianni Papi Art Historian specializing in Caravaggio. Bonaventura Bassegoda Catedràtic, Universitat Autònoma de Edward Payne Assistant Professor in Art History, Aarhus University. Manuscripts may be sent at any time and will be reviewed by members of the journal’s Editorial Committee, composed of Barcelona. -

Last Supper) HIGH RENAISSANCE: Leonardo’S Last Supper

INNOVATION and EXPERIMENTATION: ART of the EARLY and HIGH RENAISSANCE (Leonardo’s Last Supper) HIGH RENAISSANCE: Leonardo’s Last Supper Online Links: Leonardo da Vinci – Wikipedia Bramante – Wikipedia Leonardo's Virgin of the Rocks - Smarthistory Leonardo's Last Supper – Smarthistory Leonardo's Last Supper - Private Life of a Masterpiece Andrea del Castagno's Last Supper - Art in Tuscany Dieric Bouts - Flemish Primitives Bouts Holy Sacrament Altarpiece - wga.hu Leonardo da Vinci. Self-Portrait Leonardo da Vinci (1452-1519), the illegitimate son of the notary Ser Piero and a peasant girl known only as Caterina, was born in the village of Vinci, outside Florence. He was apprenticed in the shop of the painter and sculptor Verrocchio until about 1476. After a few years on his own, Leonardo traveled to Milan in 1482 or 1483 to work for the Sforza court. In fact, Leonardo spent much of his time in Milan on military and civil engineering projects, including an urban-renewal plan for the city. Leonardo da Vinci. Virgin of the Rocks, c. 1485, oil on wood The Virgin of the Rocks was painted around 1508 for a lay brotherhood, the Confraternity of the Immaculate Conception, of San Francesco in Milan. Two versions survive, an earlier one, begun 1483, in the Louvre, and a later one of c. 1508 in the National Gallery in London. There is no general agreement, but the majority of scholars concede that the Louvre panel is earlier and entirely by Leonardo, whereas the London panel, even if designed by the master, shows passages of pupils’ work consistent with the date of 1506, when there was a controversy between the artists and the confraternity. -

Leonardo Da Vinci

© 2017 Alisha Gratehouse, masterpiecesociety.com 1 Masterpiece Society Art Appreciation: Leonardo da Vinci Masterpiece Society Art Appreciation: Leonardo da Vinci © 2017 Alisha Gratehouse. All Rights Reserved. Copyright Notice: This curriculum may not be reproduced, displayed, modified, stored or transmitted in whole or in part, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical or other- wise, without prior written consent of the author. One copy of this curriculum may be printed for your own personal use. Most images in this lesson are from Wikimedia Commons and are public domain. Fair Use Notice: This curriculum may also contain copyrighted images, the use of which is not always specifically authorized by the copyright owner. However, for the purpose of art appreciation and enrichment, we are making such material available. We believe this constitutes “fair use” of any such copyrighted material for research and educational purposes as provided for in sections 17 U.S.C. § 106 and 17 U.S.C. §107. No copyright infringement is intended. © 2017 Alisha Gratehouse, masterpiecesociety.com 2 FIGURE 1 - MUSÉE DU LOUVRE, PARIS, FRANCE “We cannot measure the influence that one or another artist has upon the child’s sense of beauty, upon his power of seeing, as in a picture, the common sights of life; he is enriched more than we know in having really looked at a single picture.” – Charlotte Mason “Being an ‘agent of civilization’ is one of the many roles ascribed to teachers. If we are to have any expectations of producing a well-educated, well-prepared generation of deep-thinking, resourceful leaders, then it is essential to give students an opportunity to review, respond to, and ultimately revere the power of the human imagination—past and present. -

OIL PAINTINGS on STONE and METAL in the SIXTEENTH and SEVENTEENTH CENTURIES a Dissertation Submitted T

MATTER(S) OF IMMORTALITY: OIL PAINTINGS ON STONE AND METAL IN THE SIXTEENTH AND SEVENTEENTH CENTURIES A Dissertation Submitted to the Temple University Graduate Board In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY By BRADLEY JAMES CAVALLO AUGUST 2017 Examining Committee Members: Tracy E. Cooper, Advisory Chair, Department of Art History Marcia B. Hall, Department of Art History Ashley D. West, Department of Art History Stuart Lingo, University of Washington © Copyright 2017 by Bradley James Cavallo All Rights Reserved ii ABSTRACT By the second decade of the twenty-first century, the preponderance of scholarship examining oil paintings made on stone slabs or metal sheets in Western Europe during the early modern period (fifteenth–eighteenth centuries) had settled on an interpretation of these artworks as artifacts of an elite taste that sought objects for inclusion in private collections of whatever was rare, curious, exquisite, or ingenious. In a cabinet of curiosities, naturalia formed by nature and artificialia made by man all complemented each other as demonstrations of marvelous things (mirabilia). Certainly small-scale paintings on stone or metal exhibited amidst these kinds of rarities aided in aggrandizing a noble or bourgeois collector’s social prestige. As well, they might have derived their interest as collectables because of the painter’s fame or increased capacity for miniaturization on copper plates, or because the painter left a slab of lapis lazuli, for example, partially uncovered to reveal its visually arresting stratigraphy or coloration. Nonetheless, while the lithic and metallic supports might have added value to the oil paintings it was not thought to add meaning. -

ANDREA DEL CASTAGNO's LAST SUPPER by Eva Maria Lundin

ANDREA DEL CASTAGNO’S LAST SUPPER by Eva Maria Lundin Under the Direction of Shelley Zuraw ABSTRACT This thesis analyzes Andrea del Castagno’s fresco of the Last Supper in the refectory of Sant’Apollonia, Florence. This study investigates the details of the commission, Castagno’s fresco in the iconographic tradition of representations of the Last Supper, the aspects which separate this Last Supper from previous examples in Florentine refectories, the fresco’s purpose in relation to its conventual setting, and also the artist’s use of both classicizing and contemporary elements and techniques. The central focus of my work is the significance of this fresco in terms of both the imagery Castagno employs and his possible sources. The purpose of this thesis is to recognize the innovative aspects of the fresco, as well as the role that Castagno played in the development of Florentine Renaissance art. INDEX WORDS: Andrea del Castagno, Castagno, Last Supper, Sant’Apollonia, Florentine refectories, Italian Renaissance painting, Fresco, Fictive marble ANDREA DEL CASTAGNO’S LAST SUPPER by Eva Maria Lundin B.A., University of Alabama, 2000 A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of The University of Georgia in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree MASTER OF ART ATHENS, GEORGIA 2006 © 2006 Eva Maria Lundin All Rights Reserved. ANDREA DEL CASTAGNO’S LAST SUPPER by Eva Maria Lundin Major Professor: Shelley Zuraw Committee: Andrew Ladis Asen Kirin Electronic Version Approved: Maureen Grasso Dean of the Graduate School The University of Georgia December 2006 iv ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank the numerous people who have helped me throughout the past two and a half years, most importantly, the faculty, staff, and my fellow graduate students at the University of Georgia. -

Metropolitan Useum Of

THE ETROPOLITAN NEWS USEUM OF ART pQp^ AT WILL M RELEASE FIFTH AYE.at 82 STREET • HEW YORK TR 9-5500 THE GREAT AGE OF FRESCO GIOTTO TO P0NT0RM0 An Exhibition of Mural Paintings and Monumental Drawings at The Metropolitan Museum of Art, September 28-November 15, 1968. For the first and only time in the history of art, a group of 70 Italian frescoes -- painted on the walls of churches, monasteries, convents, and palaces in and near Florence 'between the 13th and l6th centuries -- have been removed from their architectural settings and have crossed the Atlantic this fall. For seven weeks, from September 28 to November 15, these masterpieces will be exhibited at The Metropolitan Museum of Art in its 13 Special Exhibition Galleries. The frescoes will never appear in this country again; once they are returned to Italy they will be installed permanently in their original sites. The frescoes are being lent by the Republic of Italy with the authorization of the Pontifical Commission on Sacred Art. The exhibition has been organized by the Soprintendenza of the Florentine Galleries and is presented in New York, through the generosity of Olivetti, worldwide manufacturers and distributors of business machines. Olivetti's grant, one of the largest ever presented to the Metropolitan by a business corporation, has been made on the occasion of the 100th anniversary of the birth of the company's founder, Camillo Olivetti. Thomas P. F. Hoving, Director of the Metropolitan, has called this exhibition "literally a transplanting to these shores of the best of the Italian Renaissance." Among the great masters of the Florentine Renaissance represented in the exhibition are Giotto, Taddeo Gaddi, Era Angelico, Masolino, Benozzo Gozzoli, Ambrogio Lorenzetti, Andrea Orcagna, Andrea del Sarto, Piero della Francesca, Pollaiuolo, Paolo Uccello, Mino da Fiesole, Nardo di Cione, Lorenzo di Bicci, Andrea del Castagno, Paolo Schiavo, Alessandro Allori, and Pontormo.