The Politics of Indigeneity, Anarchist Praxis, and Decolonization

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Horizontalism

Praise for Horizontalism "To read this book is to join the crucial conversation taking place within its pages: the inspiring, maddening, joyful cacophony of debate among movements building a genuinely new politics. Through her deeply re spectful documentary editing, Marina Sitrin has produced a work that embodies the values and practices it portrays." -Avi Lewis and Naomi Klein, co-creators of The Take "This book is really excellent. It goes straight to the important issues and gets people to talk about them in their own words. The result is a fascinating and important account of what is fresh and new about the Argentinian uprising."-John Holloway, author of Change the World Without Taking Power '' 'Another world is possible' was the catch-phrase of the World Social Forum, but it wasn't just possible; while the north was dreaming, that world was and is being built and lived in many parts of the global south. With the analytical insight of a political philosopher, the investigative zeal of a reporter, and the heart of a sister, Marina Sitrin has immersed herself in one of the most radical and important of these other worlds and brought us back stories, voices, and possibilities. This book on the many facets, phases and possibilities of the insurrections in Argentina since the economic implosion of December 2001 is riveting, moving, and profoundly important for those who want to know what revolution in our time might look like."-Rebecca Solnit, author of Savage Dreams and Hope in the Dark "This is the story of how people at the bottom turned Argentina upside down-told by those who did the overturning. -

Markets Not Capitalism Explores the Gap Between Radically Freed Markets and the Capitalist-Controlled Markets That Prevail Today

individualist anarchism against bosses, inequality, corporate power, and structural poverty Edited by Gary Chartier & Charles W. Johnson Individualist anarchists believe in mutual exchange, not economic privilege. They believe in freed markets, not capitalism. They defend a distinctive response to the challenges of ending global capitalism and achieving social justice: eliminate the political privileges that prop up capitalists. Massive concentrations of wealth, rigid economic hierarchies, and unsustainable modes of production are not the results of the market form, but of markets deformed and rigged by a network of state-secured controls and privileges to the business class. Markets Not Capitalism explores the gap between radically freed markets and the capitalist-controlled markets that prevail today. It explains how liberating market exchange from state capitalist privilege can abolish structural poverty, help working people take control over the conditions of their labor, and redistribute wealth and social power. Featuring discussions of socialism, capitalism, markets, ownership, labor struggle, grassroots privatization, intellectual property, health care, racism, sexism, and environmental issues, this unique collection brings together classic essays by Cleyre, and such contemporary innovators as Kevin Carson and Roderick Long. It introduces an eye-opening approach to radical social thought, rooted equally in libertarian socialism and market anarchism. “We on the left need a good shake to get us thinking, and these arguments for market anarchism do the job in lively and thoughtful fashion.” – Alexander Cockburn, editor and publisher, Counterpunch “Anarchy is not chaos; nor is it violence. This rich and provocative gathering of essays by anarchists past and present imagines society unburdened by state, markets un-warped by capitalism. -

Download As a PDF File

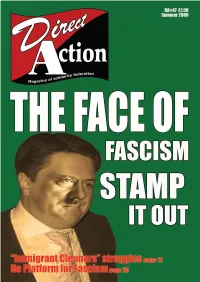

Direct Action www.direct-action.org.uk Summer 2009 Direct Action is published by the Aims of the Solidarity Federation Solidarity Federation, the British section of the International Workers he Solidarity Federation is an organi- isation in all spheres of life that conscious- Association (IWA). Tsation of workers which seeks to ly parallel those of the society we wish to destroy capitalism and the state. create; that is, organisation based on DA is edited & laid out by the DA Col- Capitalism because it exploits, oppresses mutual aid, voluntary cooperation, direct lective & printed by Clydeside Press and kills people, and wrecks the environ- democracy, and opposed to domination ([email protected]). ment for profit worldwide. The state and exploitation in all forms. We are com- Views stated in these pages are not because it can only maintain hierarchy and mitted to building a new society within necessarily those of the Direct privelege for the classes who control it and the shell of the old in both our workplaces Action Collective or the Solidarity their servants; it cannot be used to fight and the wider community. Unless we Federation. the oppression and exploitation that are organise in this way, politicians – some We do not publish contributors’ the consequences of hierarchy and source claiming to be revolutionary – will be able names. Please contact us if you want of privilege. In their place we want a socie- to exploit us for their own ends. to know more. ty based on workers’ self-management, The Solidarity Federation consists of locals solidarity, mutual aid and libertarian com- which support the formation of future rev- munism. -

The Making and Unmaking of Ethnic Boundaries: a Multilevel Process Theory1

The Making and Unmaking of Ethnic Boundaries: A Multilevel Process Theory1 Andreas Wimmer University of California, Los Angeles Primordialist and constructivist authors have debated the nature of ethnicity “as such” and therefore failed to explain why its charac- teristics vary so dramatically across cases, displaying different de- grees of social closure, political salience, cultural distinctiveness, and historical stability. The author introduces a multilevel process theory to understand how these characteristics are generated and trans- formed over time. The theory assumes that ethnic boundaries are the outcome of the classificatory struggles and negotiations between actors situated in a social field. Three characteristics of a field—the institutional order, distribution of power, and political networks— determine which actors will adopt which strategy of ethnic boundary making. The author then discusses the conditions under which these negotiations will lead to a shared understanding of the location and meaning of boundaries. The nature of this consensus explains the particular characteristics of an ethnic boundary. A final section iden- tifies endogenous and exogenous mechanisms of change. TOWARD A COMPARATIVE SOCIOLOGY OF ETHNIC BOUNDARIES Beyond Constructivism The comparative study of ethnicity rests firmly on the ground established by Fredrik Barth (1969b) in his well-known introduction to a collection 1 Various versions of this article were presented at UCLA’s Department of Sociology, the Institute for Migration Research and Intercultural Studies of the University of Osnabru¨ ck, Harvard’s Center for European Studies, the Center for Comparative Re- search of Yale University, the Association for the Study of Ethnicity at the London School of Economics, the Center for Ethnicity and Citizenship of the University of Bristol, the Department of Political Science and International Relations of University College Dublin, and the Department of Sociology of the University of Go¨ttingen. -

Chicana/Os Disarticulating Euromestizaje By

(Dis)Claiming Mestizofilia: Chicana/os Disarticulating Euromestizaje By Agustín Palacios A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Ethnic Studies in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Laura E. Pérez, Chair Professor José Rabasa Professor Nelson Maldonado-Torres Universtiy of California, Berkeley Spring 2012 Copyright by Agustín Palacios, 2012 All Rights Reserved. Abstract (Dis)Claiming Mestizofilia: Chicana/os Disarticulating Euromestizaje by Agustín Palacios Doctor of Philosophy in Ethnic Studies University of California, Berkeley Professor Laura E. Pérez, Chair This dissertation investigates the development and contradictions of the discourse of mestizaje in its key Mexican ideologues and its revision by Mexican American or Chicana/o intellectuals. Great attention is given to tracing Mexico’s dominant conceptions of racial mixing, from Spanish colonization to Mexico’s post-Revolutionary period. Although mestizaje continues to be a constant point of reference in U.S. Latino/a discourse, not enough attention has been given to how this ideology has been complicit with white supremacy and the exclusion of indigenous people. Mestizofilia, the dominant mestizaje ideology formulated by white and mestizo elites after Mexico’s independence, proposed that racial mixing could be used as a way to “whiten” and homogenize the Mexican population, two characteristics deemed necessary for the creation of a strong national identity conducive to national progress. Mexican intellectuals like Vicente Riva Palacio, Andrés Molina Enríquez, José Vasconcelos and Manuel Gamio proposed the remaking of the Mexican population through state sponsored European immigration, racial mixing for indigenous people, and the implementation of public education as a way to assimilate the population into European culture. -

Beyond Empire and Nation (CS6)-2012.Indd 1 11-09-12 16:57 BEYOND EMPIRE and N ATION This Monograph Is a Publication of the Research Programme ‘Indonesia Across Orders

ISBN 978-90-6718-289-8 ISBN 978-90-6718-289-8 9 789067 182898 9 789067 182898 Beyond empire and nation (CS6)-2012.indd 1 11-09-12 16:57 BEYOND EMPIRE AND N ATION This monograph is a publication of the research programme ‘Indonesia across Orders. The reorganization of Indonesian society.’ The programme was realized by the Netherlands Institute for War Documentation (NIOD) and was supported by the Dutch Ministry of Health, Welfare and Sport. Published in this series by Boom, Amsterdam: - Hans Meijer, with the assistance of Margaret Leidelmeijer, Indische rekening; Indië, Nederland en de backpay-kwestie 1945-2005 (2005) - Peter Keppy, Sporen van vernieling; Oorlogsschade, roof en rechtsherstel in Indonesië 1940-1957 (2006) - Els Bogaerts en Remco Raben (eds), Van Indië tot Indonesië (2007) - Marije Plomp, De gentleman bandiet; Verhalen uit het leven en de literatuur, Nederlands-Indië/ Indonesië 1930-1960 (2008) - Remco Raben, De lange dekolonisatie van Indonesië (forthcoming) Published in this series by KITLV Press, Leiden: - J. Thomas Lindblad, Bridges to new business; The economic decolonization of Indonesia (2008) - Freek Colombijn, with the assistance of Martine Barwegen, Under construction; The politics of urban space and housing during the decolonization of Indonesia, 1930-1960 (2010) - Peter Keppy, The politics of redress; war damage compensation and restitution in Indonesia and the Philippines, 1940-1957 (2010) - J. Thomas Lindblad and Peter Post (eds), Indonesian economic decolonization in regional and international perspective (2009) In the same series will be published: - Robert Bridson Cribb, The origins of massacre in modern Indonesia; Legal orders, states of mind and reservoirs of violence, 1900-1965 - Ratna Saptari en Erwiza Erman (ed.), Menggapai keadilan; Politik dan pengalaman buruh dalam proses dekolonisasi, 1930-1965 - Bambang Purwanto et al. -

Fanon's Black Skin, White Masks on Race Consciousness by Carolyn

Fanon’s Black Skin, White Masks on Race Consciousness by Carolyn Cusick, Vanderbilt University Readers of Fanon’s Black Skin, White Masks often disagree about whether or not Fanon is arguing for or against the perpetuation of racial categories.1 One interpretation suggests that Fanon’s sociogenic analysis demonstrates the inevitability, if not the necessity, of racial categories. These readers, namely Kathryn Gines in “Fanon and Sartre 50 Years Later: To Retain or Reject the Concept of Race”2 focus on Chapter Five, “The Lived Experience of the Black.” Originally published as a response to Sartre’s “Black Orpheus,” Fanon’s essay introduced Léopold Senghor’s anthology of négritude poetry. In “Black Orpheus” Sartre claims that the négritude movement is essential for a new kind of humanism that will free us from racist thinking, free us from a world divided by race: The unity which will come eventually, bringing all oppressed peoples together in the same struggle, must be preceded in the colonies by what I shall call the moment of separation or negativity: this anti-racist racism is the only road that will lead to the abolition of racial differences.3 Fanon’s response is direct: “Jean-Paul Sartre, in this work, has destroyed black zeal. … I needed not to know. This struggle, this new decline had to take on an aspect of completeness.”4 Sartre’s declaring an end to racialism undermines the power of experiencing blackness positively; rendering it as a temporary move on the way to universal humanism makes it almost powerless. To succeed, négritude has to be able to be experienced as absolute. -

New Anarchist Review Advertising in the Newanarchist Review June 1985, While on Their C/O 84B Whitechapel High Street Costs from £10 a Quarter Page

i 3 Balmoral Place Stirling, Scotland For trade distribution contact FK8 2RD 84b Whitechapel High Street London E1 7QX M A I L OR D E R Tel/fax 081 558 7732 DISTRIBUTION R iii-'\%1[_ X6%LE; 1/ ‘3 _|_i'| NI Iii O ‘Puxlci-IUi~lF G %*%ad,J\..1= BLACK _..ni|.miu¢ _ RED I BLQCK ... Rnmcho-lymhcufld *€' BREEN a BLMIK.....iiiuachv-Queen ,1-\ Plianchmle 5;7P%""¢5 L0 ..,....0u ab»! ’____ : <*REE"--I-=~‘~siw mi. Punchline *8: Let us Pray "'""~" 9"" Punchline *9: Time to remove GREEN 5 PURPLE.....Uc.ncn4 Jufflu N TFllAI\IGl_ESRq, ____, ,,,,,,,,,, Punchline ,10: Censorship oi bi"EEl'L ,,,l -znwiuli 8 $g?L":]":' """*'”"‘ L?;LB5"£5"";" Each copy £1 (post pai'd) in UK. M, ,,'f,‘;,'1;¢.5 are 11 30 Mm European orders £1.20 (post paid) mmoguijifgmflgrmfj, Mme European wholesale welcome Make cheques payable to ‘J Elliott’ only. Big Bang, Plain Wrapper comix, Punchline, Fixed Grin, Anti Shirts Catalogue from: BM ACTIVE LONDON WC1 N 3XX, LONDO 1M1Nflilllillilfilll __-rwuew ANARCH‘: ' ' '1... l'|1W ANARCHIST REVIEW NEW TITLES These titles are available from A Distribution (trade) counts what happened to No. 21 S September 1992 and AK Press (mail order) unless otherwise stated. several hundred travellers, See back page for addresses. who were attacked in a mili- Published by: Advertise taiy-style police operation in New Anarchist Review Advertising in the NewAnarchist Review June 1985, while on their c/o 84b Whitechapel High Street costs from £10 a quarter page. Series ANARCHY BY AN druggists’, or hard by a win- way to the Stonehenge festi- London E1 7QX discounts available. -

Revolution by the Book

AK PRESS PUBLISHING & DISTRIBUTION SUMMER 2009 AKFRIENDS PRESS OF SUMM AK PRESSER 2009 Friends of AK/Bookmobile .........1 Periodicals .................................51 Welcome to the About AK Press ...........................2 Poetry/Theater...........................39 Summer Catalog! Acerca de AK Press ...................4 Politics/Current Events ............40 Prisons/Policing ........................43 For our complete and up-to-date AK Press Publishing Race ............................................44 listing of thousands more books, New Titles .....................................6 Situationism/Surrealism ..........45 CDs, pamphlets, DVDs, t-shirts, Forthcoming ...............................12 Spanish .......................................46 and other items, please visit us Recent & Recommended .........14 Theory .........................................47 online: Selected Backlist ......................16 Vegan/Vegetarian .....................48 http://www.akpress.org AK Press Gear ...........................52 Zines ............................................50 AK Press AK Press Distribution Wearables AK Gear.......................................52 674-A 23rd St. New & Recommended Distro Gear .................................52 Oakland, CA 94612 Anarchism ..................................18 (510)208-1700 | [email protected] Biography/Autobiography .......20 Exclusive Publishers CDs ..............................................21 Arbeiter Ring Publishing ..........54 ON THE COVER : Children/Young Adult ................22 -

Cultural Nationalism E R I C Ta Y L O R Wo O D S, 2016

Cultural Nationalism E r i c Ta y l o r Wo o d s, 2016 INTRODUCTION Nationalism may involve the combination of culture and politics, but for many of its most prominent students, the former is subordinate to the latter. In this view, nationalist appeals to culture are a means to a political end; that is, the achievement of statehood. Hence, for Ernest Gellner (2006 [1983]: 124), culture is but an epiphenomenon, a ‘false- consciousness … hardly worth analyzing …’. For their part, Eric Hobsbawm and Terrence Ranger (1983) suggest that national traditions are ‘invented’ by elites concerned with the legitimization of state power. Similarly, John Breuilly (2006 [1982]: 11) defines national movements as ‘political movements … which seek to gain or exercise state power and justify their objectives in terms of nationalist doctrine’. A broadly similar characterization of nationalism can be found in the writings of many other esteemed scholars (Giddens, 1985; Laitin, 2007; Mann, 1995; Tilly, 1975). The privileging of politics over culture remains the dominant approach to understanding nationalism, but it is not without criticism. There is now a vast and rapidly growing body of literature insisting that the role of culture should be made more prominent. In opposition to the argument that nationalist appeals to culture are but an exercise in legitimation, this body of literature suggests that they can be ends unto themselves. This latter phenomenon, generally referred to as cultural nationalism, is the subject of this chapter. The chapter proceeds as follows. I begin with the definition and history of cultural nationalism before discussing several key themes in its study. -

Leaving the Left Behind 115 Post-Left Anarchy?

Anarchy after Leftism 5 Preface . 7 Introduction . 11 Chapter 1: Murray Bookchin, Grumpy Old Man . 15 Chapter 2: What is Individualist Anarchism? . 25 Chapter 3: Lifestyle Anarchism . 37 Chapter 4: On Organization . 43 Chapter 5: Murray Bookchin, Municipal Statist . 53 Chapter 6: Reason and Revolution . 61 Chapter 7: In Search of the Primitivists Part I: Pristine Angles . 71 Chapter 8: In Search of the Primitivists Part II: Primitive Affluence . 83 Chapter 9: From Primitive Affluence to Labor-Enslaving Technology . 89 Chapter 10: Shut Up, Marxist! . 95 Chapter 11: Anarchy after Leftism . 97 References . 105 Post-Left Anarchy: Leaving the Left Behind 115 Prologue to Post-Left Anarchy . 117 Introduction . 118 Leftists in the Anarchist Milieu . 120 Recuperation and the Left-Wing of Capital . 121 Anarchy as a Theory & Critique of Organization . 122 Anarchy as a Theory & Critique of Ideology . 125 Neither God, nor Master, nor Moral Order: Anarchy as Critique of Morality and Moralism . 126 Post-Left Anarchy: Neither Left, nor Right, but Autonomous . 128 Post-Left Anarchy? 131 Leftism 101 137 What is Leftism? . 139 Moderate, Radical, and Extreme Leftism . 140 Tactics and strategies . 140 Relationship to capitalists . 140 The role of the State . 141 The role of the individual . 142 A Generic Leftism? . 142 Are All Forms of Anarchism Leftism . 143 1 Anarchists, Don’t let the Left(overs) Ruin your Appetite 147 Introduction . 149 Anarchists and the International Labor Movement, Part I . 149 Interlude: Anarchists in the Mexican and Russian Revolutions . 151 Anarchists in the International Labor Movement, Part II . 154 Spain . 154 The Left . 155 The ’60s and ’70s . -

Indigenism and Cultural Authenticity in Brazilian Amazonia

Department of Anthropology Goldsmiths Anthropology Research Papers Indigenism and Cultural Authenticity in Brazilian Amazonia Stephen Nugent Indigenism and Cultural Authenticity in Brazilian Amazonia Stephen Nugent GARP 15 Goldsmiths College 2009 Goldsmiths Anthropology Research Papers Editors: Mao Mollona, Emma Tarlo, Frances Pine, Olivia Swift The Department of Anthropology at Goldsmiths is one of the best in Europe, specialising in innovative research of contemporary relevance. We are proud of what we have achieved since our formal beginnings in 1985, and in particular of the way that people in the department – students, staff and researchers – have sought to engage critically and creatively with the traditions of anthropology. Our research interests are broad and include visual art, labour and human rights activism, indigenous politics, gentrification, security and terrorism, fashion, gender, health and the body. The department combines a strong ethnographic expertise in Africa, South Asia, Latin America, Europe, the Pacific and Caribbean, with a broader focus on regional inter-connections, inter-dependencies and developments. We hope that Goldsmiths Academic Research Papers will provide a platform to communicate some of the work that makes the Goldsmiths department distinctive. It includes articles by members of academic staff, research fellows, PhD and other students. GARP Number 15 ©Goldsmiths College, University of London and Stephen Nugent 2009 Cover image courtesy of Museo do Indio, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil Stephen Nugent teaches anthropology at Goldsmiths. His most recent book is Scoping the Amazon: Image, Icon Ethnography (2007). ISBN 9781-9041-58981 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced in any form or by any means without the permission of the publishers or the authors concerned.