Bordeaux Wines.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Le Vignoble De Pessac-Léognan Et Des Graves

Le vignoble de Pessac Léognan Le vignoble de Pessac-Léognan et des Graves Photo : Château carbonnieux ! Ecole du vin muscadelle www.ecole-muscadelle.fr ! 1 Le vignoble de Pessac Léognan Introduction L’AOC pessac-léognan est jeune, elle a vu le jour en 1987. Pourquoi une création si tardive? Pourquoi avoir voulu se différencier de l’ AOC graves dont elle faisait partie? Pourquoi un seul vin rouge de la région des Graves, Château Haut-Brion, a-t’il été sélectionné pour faire partie des grands crus classés de 1855 alors les vins liquoreux de cette zone ont un classement rien que pour eux? Durant ce cours, l’idée sera de vous donner les grandes lignes de la spécificité de cette AOC prestigieuse et de mieux vous faire comprendre sa relation à l’AOC graves, au Sauternais, au reste du vignoble bordelais et à la ville de Bordeaux. Pour ceux qui n’ont pas encore eu le loisir de visiter cette région, je vous invite à le faire, le vignoble est en certains endroits totalement fondu dans la ville, mais en cherchant bien on le trouve. Localisation Le vignoble des Graves se trouve en région Aquitaine, dans le département de la Gironde, sur la rive gauche de la Garonne, autour de la ville de Bordeaux. Il est délimité au nord par la commune d’Eysines et du Haillan, à l’est par la ville de Bordeaux dans laquelle certains châteaux ont pu résister comme Haut-Brion ou Pape-Clément, à l’ouest par les landes et au sud par Mazères, Langon et Saint-Pierre-de-Mons. -

Vintage Notes

VINTAGE NOTES The following chart is a compilation (or cuvee if you will!) of notes from the major Bordeaux critics – Jancis Robinson (JR), Decanter (DC), Wine Spectator (WS), Robert Parker (RP), James Suckling (JS), as well as the lesser known, but thorough, website – Wine Cellar Insider (WCI). If there is anything that was solidified while compiling all the information, is that each critic can have widely different opinions regarding each appellation and each vintage, which can result in conflicting information with regards to the quality. The best advice is to find a critic whose palate and assessments you respect and align with your own palate. This is by no means meant to be taken as gospel, but rather hopefully a way to view & compare several opinions about each vintage in a succinct way, rather than flipping through various tabs and websites. Although there was some editing done on our part on the verbiage used by each publication, we did our best to remain true to their words. Not every vintage has notes from each critic for a few reasons – their publication didn’t offer anything specific enough, or any information at all in some cases, or just a blanket assessment was offered. If there are specific appellations mentioned in each column, it’s referring to the lauded overall quality of the appellation for that vintage. One of the top 3 questions any wine professional or Sommelier is often asked “when can I drink this (insert wine name here)? The answer is rarely an easy one but there is this basic guideline you can follow: if you like your wines to have big fruit flavours and assertive structure, drink the wine soon (and don’t forget to decant it), if you prefer to drink wines that are starting to show tertiary or savoury characteristics (more earthy and leather notes, maybe some smokiness and mushroom), tuck the bottle to the back corner of your cellar or wine fridge and try to forget about it for a few years. -

Lalande-De-Pomerol

cut lines KERMIT LYNCH WINE MERCHANT KERMIT LYNCH WINE MERCHANT KERMIT LYNCH WINE MERCHANT Importer of fine wine from France and Italy Importer of fine wine from France and Italy Importer of fine wine from France and Italy WWW.KERMITLYNCH.COM WWW.KERMITLYNCH.COM WWW.KERMITLYNCH.COM LALANDE-DE-POMEROL LALANDE-DE-POMEROL LALANDE-DE-POMEROL CHÂTEAU BELLES-GRAVES CHÂTEAU BELLES-GRAVES CHÂTEAU BELLES-GRAVES Bordeaux, France Bordeaux, France Bordeaux, France The finesse, silky tannins, and pure class The finesse, silky tannins, and pure class The finesse, silky tannins, and pure class of this red Bordeaux really make an of this red Bordeaux really make an of this red Bordeaux really make an impression. Have you noticed, by the impression. Have you noticed, by the impression. Have you noticed, by the way, that Kermit never took the jammy, way, that Kermit never took the jammy, way, that Kermit never took the jammy, oaky Bordeaux route? oaky Bordeaux route? oaky Bordeaux route? MERLOT MERLOT MERLOT CABERNET FRANC CABERNET FRANC CABERNET FRANC LEARN MORE LEARN MORE LEARN MORE KERMIT LYNCH WINE MERCHANT KERMIT LYNCH WINE MERCHANT KERMIT LYNCH WINE MERCHANT Importer of fine wine from France and Italy Importer of fine wine from France and Italy Importer of fine wine from France and Italy WWW.KERMITLYNCH.COM WWW.KERMITLYNCH.COM WWW.KERMITLYNCH.COM LALANDE-DE-POMEROL LALANDE-DE-POMEROL LALANDE-DE-POMEROL CHÂTEAU BELLES-GRAVES CHÂTEAU BELLES-GRAVES CHÂTEAU BELLES-GRAVES Bordeaux, France Bordeaux, France Bordeaux, France The finesse, silky tannins, and pure class The finesse, silky tannins, and pure class The finesse, silky tannins, and pure class of this red Bordeaux really make an of this red Bordeaux really make an of this red Bordeaux really make an impression. -

Structure in Wine Steiia Thiast

Structure in Wine steiia thiAst What is Structure? • So what is this thing, structure? It*s the sense you have that the wine has a well-established form,I think ofit as the architecture ofthe wine. A wine with a great structure will often remind me ofthe outlines of a cathedral, or the veins in a leaf...it supports, and balances the fiuit characteristics ofthe wine. The French often describe structure as the skeleton ofthe wine, as opposed to its flavor which they describe as the flesh. • Where does structure come firom? In white wines, it usually comes from alcohol or acidity; in red wines, it comes from a combination of acidity and tannin, a component in the grapes' skins and seeds. Thus, wines with a lot of tannin (like cabernet) also have a lot of structure. Beaujolais is made from gamay which does not have much tannin. As a result, Beaujolais can lack structure; it feels soft, flat or simple in the mouth (though its flavors can certainly still be attractive). • While structure is hard to articulate, you can easily taste or sense it —^and the lack of it. • Understanding structure is critical to understanding any ofthe ''powerful" red varieties: cabernet sauvignon, merlot, syrah, nebbiolo, tempranillo, and malbec, to name a few. I just don't think you can understand these wines unless you understand structure, and how it frames and focuses the powerful rush of fruit. It adds freshness, and a "lightness" to the density ofripe fiuit. Structure matters when pairing wine and food. Foods with a lot of structure themselves— like a meaty, thick steak-need wines with commensurate structure (like cabernet), or the food experience can dwarfthe wine experience. -

Capricci Wine List

CAPRICCI WINE LIST AT CAPRICCI YOU CAN CHOOSE FROM A LARGE SELECTION OF WINE TO SUIT YOUR TASTE, BELOW IS OUR WINE LIST FOCUSING ON THE MOST POPULAR WINES FROM THE SHELF AS WELL AS A SOME HAND SELECTED MORE PRESTIGIOUS WINES. IN THE LIST WE HAVE INCLUDED SOME PERSONAL RECOMMENDATIONS OF WINES TO DRINK BY THE BOTTLE HERE AT CAPRICCI. PLEASE DON'T HESITATE TO ASK OUR STAFF FOR ANY ADVICE OR INFORMATION ON THE WINES OR FOR SPECIAL TAKE AWAY PRICES. ** OUR BUBBLES** Prosecco Sottoriva Col Fondo, Malibran (Veneto) ........................................................................... £32,00 Col Fondo, (Sur-lie) literally means "on the yeasts". This Prosecco has no added sulfites and it’s characterized by a fine perlage and intense and complex notes of ripe fruit, bread crust and yeasts. Monte Rossa, Franciacorta DOCG P.R. Brut Blanc de Blanc (Lombardy) ...................................... £53,00 It was created to celebrate 35 years of the Estate, named after the founders of the Vinery with the same initials: Paola Rovetta and her husband Paolo Rabotti. It is a Blanc de Blancs, with an harmony between the amplitude, the structure, the complexity of reserve wine (35%) and elegance, smoothness and refinement typical of the Chardonnay (65%). Cavalleri, Franciacorta DOCG Blanc de Blancs (Lombardy) ............................................................ £56,00 The cuvée is produced by blending wines derived from DOCG located on the hills around Erbusco in Franciacorta: most come from the most recent harvest available and 20% is derived from the previous years, specifically stored at low temperature. Brut Blanc de Blancs cuvée is a Chardonnay which shows great elegance and finesse, and a surprising evolutionary behaviour. -

Publication of a Communication of Approval of a Standard

29.7.2019 EN Official Journal of the European Union C 254/3 V (Announcements) OTHER ACTS EUROPEAN COMMISSION Publication of a communication of approval of a standard amendment to the product specification for a name in the wine sector referred to in Article 17(2) and (3) of Commission Delegated Regulation (EU) 2019/33 (2019/C 254/03) This notice is published in accordance with Article 17(5) of Commission Delegated Regulation (EU) 2019/33 (1). COMMUNICATION OF APPROVAL OF A STANDARD AMENDMENT ‘Haut-Médoc’ Reference number: PDO-FR-A0710-AM03 Date of communication: 10.4.2019 DESCRIPTION OF AND REASONS FOR THE APPROVED AMENDMENT 1. Demarcated parcel area Description and reasons This application includes the applications with reference PDO-FR-A0710-AM01 and PDO-FR-A0710-AM02, submit ted on 7 April 2016 and 12 January 2018, respectively. The following is inserted in chapter I, point IV(2) of the specification after the words ‘16 March 2007’: ‘ 28 September 2011, 11 September 2014, 9 June 2015, 8 June 2016, 23 November 2016 and 15 February 2018, and of its standing committee of 25 March 2014’. The purpose of this amendment is to add the dates on which the competent national authority approved changes to the demarcated parcel area within the geographical area of production. Parcels are demarcated by identifying the parcels within the geographical area of production that are suitable for producing the product covered by the regis tered designation of origin in question. Accordingly, as a r esult of this amendment, a new point (b) has been added -

Vinoetceterajune 2020 MAGAZINE | WINE | TRAVEL | COMMUNITY | FOOD | TRENDS

vinoetceteraJUNE 2020 MAGAZINE | WINE | TRAVEL | COMMUNITY | FOOD | TRENDS WE’LL ALWAYS HAVE FRANCE EDITORIAL MASTER PIECE Bordeaux, Bergerac, Wine in the Time of Covid Beaujolais | Name a Jane Masters MW is Opimian’s Master of Wine Covid-19 has turned lives and livelihoods upside Better Trio! down. Countries have been in varying degrees of Zoé Cappe, Editor-in-Chief lockdown. Shops selling essential items are open with social distancing measures in place, and online shopping cannot keep up with demand. In most cases restaurants and bars, which usually represent a large proportion of wine sales, are shut. Nature cannot be put on hold. At the start of lockdown, the Southern Hemisphere was in harvest mode with grapes being picked in Australia, New Zealand, Chile, Argentina and South Africa. Although social distancing measures were imposed, These three French regions are, of the impact on grapes and wine production course, known for their incredible wines, has been limited. In the Northern Hemisphere, the growing their fabulous cuisine and their gorgeous cycle proceeds with vineyards sprouting and the usual landscapes. It may be some time before concerns about spring frosts. The workforce is reduced as we’re able to travel to France, but at workers stay at home to look after children or to self-isolate. least we can transport ourselves there Lockdown has severely restricted transport and wine through the pictures and words of Vino shipments from regions such as northern Italy. Etcetera and the wines of this Cellar Offering. More wine is being bought for home consumption and online Unfortunately, the effects of the coronavirus pandemic on the wine sales have grown. -

The Wine List

The Wine List Here at Balzem we have taken extra time to design a wine program that celebrates the artisans, farmers and passionate winemakers who have chosen to make a little bit of wine that is unique, hand-made, true to its terroir and delicious rather than making giant amounts of wine that all tastes the same to please the masses. Champagne, Sparkling and Rosé Wines. page 1 ~~~~~~ Light & Crisp White Wines. page 2 Medium Bodied & Smooth White Wines. page 3 Full Bodied & Rich White Wines. page 4 ~~~~~~ Light & Aromatic Red Wines. page 5 Medium Bodied & Smooth Red Wines. .page 6 Full Bodied & Rich Red Wines. page 7 and 8 ~~~~~~ Seasonal Selections. page 9 California Beauties, Dessert Wines . page 10 and 11 Cocktails & Beer. page 12 Champagne & Sparkling Wines #02. Saumur Rosé N.V. Louis de Grenelle, Loire ValleY – FR 17/glass; 67/bottle #03. Prosecco 2019 Scarpetta, Friuli – IT 57/bottle #04. Pinot Meunier, Champagne, Brut N.V. Jose Michel, Champagne – FR 89/bottle Rosé Wine #06. Côtes de Provence, Quinn Rosé 2019 Provence – FR 17/glass; 57/bottle #07. Côtes de Provence, Domaine Jacourette 2016 Magnum (1,5L) Provence – FR 73/Magnum 1 Light & Crisp White Wines On this page you will find wines that are fresh, dry and bright they typically pair well with warm days, seafood or the sipper who prefers dry, crisp, bright wines. The smells and flavors are a range of citrus notes and wild flowers. Try these if you like Sauvignon Blanc or Pinot Grigio #08. Verdejo, Bodegas Menade 2019 (Sustainable) Rueda – SP 13/glass #09. -

Frank Phélan Saint-Estèphe AOC Bordeaux Wine Region of France

Bordeaux Wine Region of France Frank Phélan Bordeaux has a temperate climate, short winters and a Saint-Estèphe AOC high degree of humidity due its closeness to the Atlantic. BORDEAUX (FRANCE) Named after region’s main city, Bordeaux is divided by Since 1985, the Gardinier brothers (Thierry, Stéphane the Gironde estuary with the majority of the vineyards and Laurent) have ensured the prestige of the château located either on its “right” or “left” bank. There are many and its heritage. The vineyard of Château Phélan Ségur sub-zones along both banks known for their exceptional covers 70 hectares of magnificent clay-gravels on the quality such as: Margaux, Saint-Julien, Pauillac, Saint- hillocks and plateaus of Saint-Estèphe. Created in 1986, Estèphe, Médoc, Saint-Emilion, and Pomerol to name a Frank Phélan, the second wine of the château, bears the few. The current permissible red grapes allowed are: name of the son of Bernard Phélan, founder of the Merlot, Cabernet Sauvignon, Cabernet Franc, Malbec estate. Frank Phélan comes from 15 hectares of old and Petite Verdot. Common white grapes allowed are vines and a selection of vines of less than ten years. It Sauvignon Blanc, Semillon and Muscadelle. respects the classic values of the château by expressing another facet of its terroir. In a broad sense, the term Médoc is typically coined as the geographical area of the Left Bank. However, the Grapes: 75% Merlot, 25% Cabernet Sauvignon AOC is comprised of these sub-regions: Haut-Médoc, Viticulture: Soil is superficial graves, clay subsoil. 12 Margaux, Listrac-Médoc, Moulis-en-Médoc, Saint-Julien, months in French oak barrique. -

First Growth 2000S Does the Market Have It All Wrong?

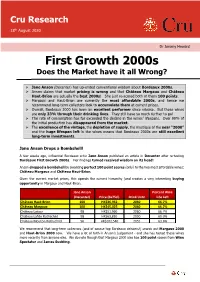

Cru Research 18th August 2020 Dr Jeremy Howard First Growth 2000s Does the Market have it all Wrong? ➢ Jane Anson (Decenter) has up-ended conventional wisdom about Bordeaux 2000s. ➢ Anson claims that market pricing is wrong and that Château Margaux and Château Haut-Brion are actually the best 2000s! She just re-scored both of them 100 points. ➢ Margaux and Haut-Brion are currently the most affordable 2000s, and hence we recommend long-term collectors look to accumulate them at current prices. ➢ Overall, Bordeaux 2000 has been an excellent performer since release. But these wines are only 33% through their drinking lives. They still have so much further to go! ➢ The rate of consumption has far exceeded the decline in the wines’ lifespans. Over 99% of the initial production has disappeared from the market. ➢ The excellence of the vintage, the depletion of supply, the mystique of the year “2000” and the huge lifespan left in the wines means that Bordeaux 2000s are still excellent long-term investments. Jane Anson Drops a Bombshell! A few weeks ago, influential Bordeaux critic Jane Anson published an article in Decanter after re-tasting Bordeaux First Growth 2000s. Her findings turned received wisdom on its head! Anson dropped a bombshell by awarding perfect 100 point scores (only) to the two most affordable wines: Château Margaux and Château Haut-Brion. Given the current market prices, this upends the current hierarchy (and creates a very interesting buying opportunity in Margaux and Haut-Brion. Jane Anson Percent Wine (Decanter) Price (6x75cl) Drink Until Life Left Château Haut-Brion 100 HK$36,952 2060 66.7% Château Margaux 100 HK$45,025 2060 66.7% Château Latour 98 HK$51,960 2060 66.7% Château Lafite Rothschild 98 HK$63,810 2050 60.0% Château Mouton Rothschild 96 HK$102,540 2055 63.6% We recommend that long-term collectors (and of course top Bordeaux drinkers!) search out Margaux 2000 and Haut-Brion 2000 now. -

Sauternes- Winebow

Sauternes 2017 W I N E D E S C R I P T I O N Château La Tour Blanche is ranked as Premier Cru Classé in the 1855 Classification of Sauternes. The estate is national property of France and home to the La Tour Blanche School of Viticulture. Emotions de La Tour Blanche is a second label, the name of which references the various emotions Sauternes evokes. A B O U T T H E V I N E Y A R D The estate is in the village of Bommes in the heart of the Sauternes appellation. Château La Tour Blanche sits at the top of a ridge of gravel over clay and limestone subsoil. This advantageous position provides the best possible exposure to the sun, optimal drainage, and a high concentration of flavors and natural sweetness. W I N E P R O D U C T I O N Emotions de La Tour Blanche consists mainly of Sémillon, with smaller percentages of Sauvignon Blanc and Muscadelle which are harvested late and selected for botrytis. The wine is vinified and aged exclusively in stainless-steel vats for 18 months to preserve its freshness and aromatic character. T A S T I N G N O T E S Due to the climate of the Sauternes region, wines are produced from grapes affected by the botrytis cinerea, a “noble rot” that develops on the berries. This phenomenon creates a high concentration of natural sugar and complex aromas of spice and dried fruits. F O O D P A I R I N G The great fine wines of Sauternes are not only dessert wines, but they can also be classically paired with foie gras in all its forms, light fish in a creamy sauce, or with strong cheeses such as Roquefort or Epoisses. -

2015 Readers Merlot

1RDRS5 20 READERS MERLOT 15 COLUMBIA VALLEY A.V.A. n outstanding Merlot from Washington’s revered old vineyards Conner Lee and Dionysus. Our Readers blend tips its hat to all exploratory readers of books and wine. Blending Conner Lee Vineyard’s 1992 old block Merlot and Dionysus Vineyards’ block A15 Merlot combines two super character vineyards. Elephant Mountain Vineyard’s Cabernet bring spice and complexity to the blend. This powerful wine offers fragrant cherries and chocolate with rich marrionberry flavors in this delicious easy drinking style. VINTAGE Vintage 2015 is Washington’s leading hot vintage and earliest ripening harvest. Our vineyards yielded fruit with record color and tannin. This is in alignment with our house style of rich and smooth age-worthy reds. Spring broke buds in March and flowered in May, setting the stage for the early harvest. Late spring developed small grapes on small clusters in all our vineyards. Summer temperatures were hotter than average and lead to an early July verasion. Together early and swift verasion are hallmarks of great vintages. Our fruit we shaded with healthy canopies balancing acidity and sugar ripeness while protecting against sunburn. We harvested summer fruits in excellent condition. WINEMAKING Dionysus we harvested August 26 into small fermenters. Conner Lee Vineyard we picked at the peak of ripeness swiftly by Pellenc Selective harvester September 10 delivering perfectly sorted fruit right on time. We hand mixed for two weeks, then finished fermentation in barrels and puncheons. We aged on lees reductively, developing savory tones complimentary to the powerful fruit. After 20 months, we selected the final blend.