In Search of Excellence in Higher Education

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

MIC 2018: Managing Global Diversities

Mic 2018 Management International Conference Managing Global Diversities Abstracts of the Joint International Conference Organised by • University of Primorska, Faculty of Management, Slovenia • Lomonosov Moscow State University, Moscow School of Economics, Russian Federation • Juraj Dobrila University of Pula, Faculty of Economics and Tourism ‘Dr. Mijo Mirković,’ Croatia • Association for the Study of East European Economies and Cultures, USA • Society for the Study of Emerging Markets, USA Bled, Slovenia • 30 May–2 June 2018 MIC 2018: Managing Global Diversities Abstracts of the Joint International Conference Organised by University of Primorska, Faculty of Management, Slovenia Lomonosov Moscow State University, Moscow School of Economics, Russian Federation Juraj Dobrila University of Pula, Faculty of Economics and Tourism, Croatia Association for the Study of East European Economies and Cultures, USA Society for the Study of Emerging Markets, USA Bled, Slovenia | 30 May–2 June 2018 Edited by Suzana Sedmak Suzana Laporšek Matjaž Nahtigal Matic Novak Patricia Blatnik Design and Layout Alen Ježovnik Published by University of Primorska Press Titov trg 4, 6000 Koper, Slovenia Editor in Chief Jonatan Vinkler Managing Editor Alen Ježovnik www.hippocampus.si Koper, Slovenia | May 2018 Management International Conference ISSN 2712-3766 © University of Primorska Press http://www.hippocampus.si/ISBN/978-961-7023-90-9.pdf Published under the terms of the Creative Commons CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 License Kataložni zapis o publikaciji (CIP) pripravili v -

Kesin-Liste.Pdf

2021-2022 ERASMUS+ ÖĞRENİM HAREKETLİLİĞİ KESİN YERLEŞTİRME SONUÇLARI Erasmus+ Öğrenim Hareketliliği Programı kapsamında yerleşen öğrencilerin HİBE ile desteklenebilmesi, Üniversitemize yeterli mali kaynağın tahsis edilmesine bağlıdır. Hibe desteği alamayan öğrenciler hibesiz olarak faaliyetten yararlanma hakkına sahiptir. 1. Yerleşen öğrenciler, haklarından vazgeçmeleri halinde en geç 30 Mart 2021 saat 17.00'ye kadar Uluslararası İlişkiler birimine dilekçe ile başvurmalıdır. Bu tarihten sonra vazgeçen öğrenciler, bir sonraki Erasmus başvurularında programdan daha önce yararlanmış kabul edilerek -10 puan uygulaması yapılacaktır. Ancak, hibelerin açıklanmasından sonra, hibe yetersizliğinden dolayı vazgeçen öğrenciler bu kuralın dışında değerlendirilir. Vazgeçen öğrenciler yedek listesine alınmazlar. 2. Yerleştirme sırasında daha önce aynı eğitim düzeyinde Erasmus faaliyetinden (Öğrenim ,Staj ve Konsorsiyum )yararlanmış olan öğrencilerin toplam başarı puanlarından her bir faaliyet için "10 puan" düşürülmüştür. 3. Yerleşen ve Yedek öğrenciler için ileri bir tarihte çevrim içi bilgilendirme toplantısı yapılacaktır. Toplantı tarihi ve saati öğrencilere e-posta ile bilgilendirilecektir. 4. Yerleştirme sırasında daha önce aynı eğitim düzeyinde yerleştirilmelerine rağmen belirtilen tarihten sonra mücbir sebebe dayanmaksızın feragat eden öğrencilerin toplam başarı puanlarından her bir faaliyet için "10 puan " düşürülmüştür. 5. 14 Ocak 2019, 27 Mayıs 2019, 20 Ocak 2020, 10 Eylül 2020 17 Şubat 2021 tarihli Erasmus+ dil sınavlarına başvuru yapıp gerekçesiz -

Opportunities for Collaboration Between Hungary and Jordan

n 896. offers a safe and friendly living environmen le cost-to-value ratio and affordable living c on: 9,9 M, rich in culture and history anguage: Hungarian is one of the 25 most ourist destinations in the is the 8th most popular + destination: ean degree is the key to global job markets Hungary. edge knowledge for a fair price ng in Hungary is a good investment. ional student environment y is a hub for big international companies an as a super vibrant youth life: system to guide you through the first period; organisations to take part in; tudent activities: excursions, special-courses, netw y to socialise and find new friends from all over the s a great place to discover World Heritage sites, ghtlife. o travel around in your spare r in Hungary or in Europe. ngarian Higher education? nge of available study fields, eg.: icine | Music | Engineering | Economics | Agricultu Hungary is a great decision – the land where traditi irements meet new ideas! highest number of scientific Nobel laureates,per c ous Hungarian innovations: r, diesel engine, helicopter, safety match, ballpoin tor, Rubik’s cube and many more… School Papal Reformed Theological Academy ary Dance Academy Pázmány Péter Catholic University n University Pentecostal Theological College f Jewish Studies Reformed Theological Academy of Sárospa ty of Technology and Economics Saint Athanasius Greek Catholic Theologic College Europe Saint Paul Academy versity Sapientia College of Theology y of Budapest Semmelweis University heological University Sola Scriptura College of Theology Széchenyi -

Partner Universities of Saimaa University of Applied Sciences

Partner universities of Saimaa University of Applied Sciences AUSTRIA Campus 02 University of Applied Sciences BELGIUM Artesis Plantijn University College Erasmus University College Brussels Haute Ecole Charlemagne PXL University College VIVES University College BRAZIL Universidade Positivo BULGARIA National Academy of Art - Sofia CHILE Universidad de Chile CHINA Beijing Technology and Business University Qilu University of Technology Tianjin University of Science and Technology CROATIA University of Applied Health Studies Zagreb CZECH REPUBLIC Czech University of Life Sciences Prague The Institute of Hospitality Management in Prague Tomas Bata University in Zlin VSB - Technicka Univerzita Ostrava DENMARK The Royal Danish Academy of Fine Arts, Schools of Visual Arts University College Capital University College of Northern Denmark ESTONIA Estonian Academy of Arts Tallinn Health College 1 Tallinn University of Technology Tartu Art College Tartu Health Care College University of Tarto FRANCE College of Art and Design Le Havre - Rouen EDC Paris Business School ENSA Limoges Universite de La Rochelle Universite de Lorraine Universite de Pau et des Pays de Ladour - UPPA Universite Lille 1 - Sciences et Technologies UPEM - Universite Paris-Est Marne-la-Vallee GERMANY Anhalt University of Applied Sciences Augsburg University of Applied Sciences Brandenburg University of Applied Sciences Dusseldorf University of Applied Sciences Erste Europaische Schule fur Physiotherapie Harz University of Applied Sciences Heilbronn University Karlsruhe University -

Erasmus 0K0l0 Anla^Ma L0stes0 Ö˚Ren0m (2021) (15)

Attention Please! : Before you choose our partner universities in your Erasmus application, please consult with your Erasmus Departmental Coordinator and check the universities web pages so that you will not have any problem during filling in your Erasmus Learning Agreement. (The list of Erasmus Departmental Coordinators is on our web page - http://erasmus.alanya.edu.tr/ ) Dikkat! : Erasmus başvurunuzda partner üniversitelerimizi tercih etmeden önce mutlaka Erasmus Bölüm Koordinatörünüze danışınız ve partner okulların internet sitelerini kontrol ediniz ki sonrasında o üniversiteye gitmeye hak kazandığınızda Erasmus Öğrenim Anlaşmasını bölüm koordinatörünüzle doldururken sorun yaşamayasınız. ( Bölüm Koordinatörleri Listesi internet sitemizde mevcuttur - http://erasmus.alanya.edu.tr/ ) Study Cycle BA: Bachelor (1st Cycle) Partner University Quota (per Language Subject Area (Study Field) Suitable Departments at ALKU MA: Master of Arts (2nd Country Cycle) (Erasmus Code) semester) Level PhD: Philosphy of Doctorate (3rd Cycle) BA Lithuania Marijampole College (LT MARIJAM01) 3 B1 Jan Grodek State Vocational Academy in Sanok (PL 0112 Training for pre-school teachers Teacher Training at Pre-School Level BA Poland 2 B1 SANOK01) BA Slovakia The University of Presov (SK PRESOV01) 2 B2 BA/MA/PhD Bulgaria Trakia University (BG STARAZ01) 3 B1 BA Hungary John Von Neumann University (HU KECSKEM03) 2 B2 BA/MA Lithuania Vytautas Magnus University (LT KAUNAS01) 2 B2 0113 Teacher training without subject Teacher Training at Primary School Level BA Portugal Polytechnic Institute of Guarda (P GUARDA01) 1 B2 specialisation BA/MA Romania Aurel Vlaicu University of Arad (RO ARAD01) 2 B1 1 Decembrie 1918 University of Alba Iulia (RO BA/MA Romania 3 B1 ALBAIU01) BA Slovakia The University of Presov (SK PRESOV01) 2 B2 SS. -

Mta Geodéziai És Geofizikai Kutatóintézet

MTA CSFK GEODETIC AND GEOPHYSICAL INSTITUTE Csatkai u. 6-8., 9400 Sopron 9401 Sopron, Pf.5. Tel: +36 99 508 343; Fax: +36 99 508 355 E-mail: [email protected], web: www.csfk.mta.hu, www.ggki.hu I. The main tasks of the institute in 2017 The object of the current basic research in the Geodetic and Geophysical Institute is the observation, modelling and interpretation of the physical condition and processes of planet Earth, as well as the development of the related theoretical (mathematical, physical) and experimental methods and instrumentation. The public responsibilities covered by our basic activity are: continuous observation of the solid Earth and the space around Earth (geodynamics, geomagnetism and aeronomy), maintenance of the national seismological network and service, provision of data associated with international cooperation, as well as operation of temporary surveillance systems. The activities of the institute that have direct economic importance are the natural resource exploration and the analysis of geological- geo- physical hazards. Research topics of the Institute that have traditionally outstanding success even by international standards are geomagnetism, magnetotellurics, seismology, aeronomy and geodynamics. Through its broadband electromagnetic measurements the Széchenyi István Geophysical Observatory of the Hungarian Academy of Sciences has a significant role in global networks of observatories and in international projects diagnosing the upper atmosphere and the plasma environment of the Earth. The Infrastructural developments from different grants (two GINOP applications: Cosmic Effects and Risks, Zero Magnetic Field Laboratory) and expanded international co-operations (ESF Topo-Europe, AlpArray, ARISE) are all building a basis for new interdisciplinary research topics. -

Cooperation in Long Term Ecological Research in Central and Eastern Europe

Cooperation in Long Term Ecological Research in Central and Eastern Europe Cooperation in Long Term Ecological Research in Central and Eastern Europe Proceedings of the ILTER Regional Workshop 22-25 June, 1999 Budapest, Hungary Edited by Kate Lajtha and Kristin Vanderbilt Oregon State University Cover design: Janet Squire Cover illustration: The polluted regions of the rivers studied in the Eastern-tributaries of the Tisa River. Figure 1 from "The ecological state of the Eastern-tributaries of the Tisa River - based on characteristics of the physico- chemical parameters, the flora and fauna" by Andrei Sárkány-Kiss and Kunigunda Macalik. Printed by Oregon State University, Printing and Mailing Services, January 2000 Lajtha, K. and K. Vanderbilt, eds. 2000. Cooperation in Long Term Ecological Research in Central and Eastern Europe: Proceedings of the ILTER Regional Workshop, 22-25 June, 1999, Budapest, Hungary. Oregon State University, Corvallis, OR. Contents: Preface Preface Kate Lajtha (Oregon State University) Edit Kovacs-Láng (Hungarian Academy of Sciences) What can we learn from site networks? Nitrate leaching from European forests: results and lessons from NITREX and other co-operative projects in W. Europe Per Gundersen (Danish Forest and Landscape Research Institute) http://intranet.lternet.edu/archives/documents/reports/ILTER/ilter_c-e_Europe/contents.html[3/3/2010 1:52:25 PM] Cooperation in Long Term Ecological Research in Central and Eastern Europe Controls on forest soil organic matter development and dynamics: chronic litter manipulation as a potential international LTER activity Knute Nadelhoffer (Ecosystems Center, Woods Hole, MA) Richard Bowden (Allegheny College) Richard Boone (University of Alaska) Kate Lajtha (Oregon State University) Air pollution and forest health in Central Europe: lessons from a regional network of sites Andrzej Bytnerowicz (USDA Forest Service/University of California) Comparative watershed studies - opportunities and limitations William H. -

RECOGNITIONS BROCHURE V27

Re cogni tion Recognition [email protected] facebook.com/languagecert.org LanguageCert linkedin.com/company/languagecert International ESOL qualifications About LanguageCert 2 LanguageCert International ESOL 3 Recognition 4 United Kingdom 6 Ofqual 6 Qualifications Wales 8 UCAS 8 BAC 9 Czech Republic 10 Greece 10 Hungary 11 Italy 12 Lithuania 12 New Zealand 13 Romania 14 Spain 15 Other Countries 15 Governance 16 Appendix 18 Con tents LanguageCert is an Awarding Organisation dedicated to language skills assessment and certification. It is a member of PeopleCert, a global leader in the certification industry, that delivers millions of exams in 200 countries. Ab VISION out To be the global leader in language qualifications MISSION To develop and deliver best-in-class language skills, assessment and certification programmes that enhance the lives, education and career prospects of candidates across the world CORE VALUES Quality, Innovation, Integrity, Passion To exceed expectations and meet the highest quality standards, LanguageCert: • develops its own language qualifications • partners with renowned global organisations to offer high-quality language skills assessment • deploys state-of-the-art, innovative and flexible exam administration technologies • offers 24/7/365 Customer Service to language schools, teachers and candidates 2 LanguageCert International ESOL LanguageCert International ESOL exams are a set of English language qualifications designed to abide by the most rigorous standards of quality and reliability. They provide a practical and user-friendly way to assess English for work, study or leisure purposes. Written and Spoken Exams can be taken independently of each other at the candidates' convenience. They can choose the qualification CEFR level they feel ready to sit for and certificates are awarded to them upon successfully passing the exams. -

Historical Land Use Dataset of the Carpathian Region (1819–1980)

Journal of Maps ISSN: (Print) 1744-5647 (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/tjom20 Historical land use dataset of the Carpathian region (1819–1980) Juraj Lieskovský, Dominik Kaim, Pál Balázs, Martin Boltižiar, Mateusz Chmiel, Ewa Grabska, Géza Király, Éva Konkoly-Gyuró, Jacek Kozak, Katarína Antalová, Tetyana Kuchma, Peter Mackovčin, Matej Mojses, Catalina Munteanu, Krzysztof Ostafin, Katarzyna Ostapowicz, Oleksandra Shandra, Premysl Stych & Volker C. Radeloff To cite this article: Juraj Lieskovský, Dominik Kaim, Pál Balázs, Martin Boltižiar, Mateusz Chmiel, Ewa Grabska, Géza Király, Éva Konkoly-Gyuró, Jacek Kozak, Katarína Antalová, Tetyana Kuchma, Peter Mackovčin, Matej Mojses, Catalina Munteanu, Krzysztof Ostafin, Katarzyna Ostapowicz, Oleksandra Shandra, Premysl Stych & Volker C. Radeloff (2018) Historical land use dataset of the Carpathian region (1819–1980), Journal of Maps, 14:2, 644-651, DOI: 10.1080/17445647.2018.1502099 To link to this article: https://doi.org/10.1080/17445647.2018.1502099 © 2018 The Author(s). Published by Informa View supplementary material UK Limited, trading as Taylor & Francis Group on behalf of Journal of Maps Published online: 21 Oct 2018. Submit your article to this journal Article views: 291 View Crossmark data Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=tjom20 JOURNAL OF MAPS 2018, VOL. 14, NO. 2, 644–651 https://doi.org/10.1080/17445647.2018.1502099 Science Historical land use dataset of the Carpathian region (1819–1980) Juraj Lieskovský a,b, Dominik Kaim c, Pál Balázs d, Martin Boltižiara, Mateusz Chmielc, Ewa Grabskac, Géza Királye, Éva Konkoly-Gyuród, Jacek Kozakc, Katarína Antalováa, Tetyana Kuchmaf, Peter Mackovčing, Matej Mojsesa, Catalina Munteanuh,i,j, Krzysztof Ostafinc, Katarzyna Ostapowiczc, Oleksandra Shandrak, Premysl Stychl and Volker C. -

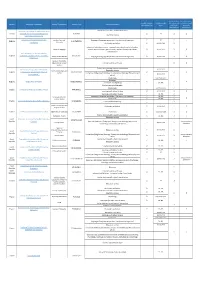

Country University/ Institution Faculty/ Department Erasmus Code Fields of Education of Students Flow Cycle Mobility for Mobility for Teaching Flows Training Flows

Possible numbers Possible numbers Possible number Mobility study of Academic staff of Academic staff Country University/ Institution Faculty/ Department Erasmus Code Fields of education of students flow cycle mobility for mobility for teaching flows training flows The University College of Teacher Education Teacher training with subject specialization Austria Vienna/Krems [Kirchliche Pädagogische A WIEN10 2 BA 2 2 Education science Hochschule Wien/Krems] University of Antwerp [Universiteit Faculty of Arts and Languages [Language acquisition; Literature and linguistics] 2 BA 2 - Belgium B ANTWERP01 Antwerpen] Philosophy Philosophy and ethics 2 BA, MA, PhD 2 - Education [Education sciense; Training for pre-school teachers; Teacher Faculty of Pedagogy training without subject specialization; Teacher training with subject 2 BA, MA, PhD 2 2 specialisation] Sofia University St. Kliment Ohridski Bulgaria [Софийски университет "Св. Климент Faculty of Slavic Studies BG SOFIA06 Languages [Language acquisition; Literature and linguistics] 2 BA, MA, PhD 2 2 Охридски"] Faculty of Philosophy- Department of Political Political sciences and civics - - 2 2 science Teacher training with subject specialization Plovdiv University „Paisii Hilendarski” BA, MA, PhD Faculty of Philosophy and Education science Bulgaria [Пловдивски университет "Паисий BG PLOVDIV04 2 2 1 History Humanities [Religion and theology; History and archeology; Philosophy and Хилендарски"] BA, MA, PhD ethics] Psychology long study cycle Education Bulgaria Burgas Free University BG BOURGAS01 -

The Crossroads of Europe

European Social The crossroads of Europe Fund INVESTING IN YOUR FUTURE HIGH QUALITY EDUCATION The history of Hungarian higher education goes back more than 650 years and builds on its unique academic heritage by integrating innovation, creativity and cooperation. EUROPEAN DEGREE WHY HUNGARY? HUNGARY? WHY Studying in Hungary means studying in Europe. Degrees earned in Hungary are recognised internationally and help you to get ahead in the global job market. AFFORDABILITY The extremely favourable cost-to-value ratio of Hungarian higher education and the affordable living costs make studying in Hungary a great investment. Scholarship opportunities are also available. CENTRAL LOCATION IN EUROPE Hungary is conveniently located in the heart of Europe. Discover unspoilt nature and numerous World Heritage sites of the country as well as other European cities within easy reach. UNFORGETTABLE CULTURAL EXPERIENCE The country has a 2000-year-old history and offers a thrilling cultural life. With its vibrant student communities and its enriching cultural scene you will never be bored. Hungary in brief & Hungarian Higher Education size: 93,000 square kilometres dimensions: 250 km (North-South) and 64 higher education institutions in Hungary 524 km (East-West) population: 9.7 million 38,500 international students from capital: Budapest (1.7 million) 163 countries (10% of the student population) currency: Hungarian Forint (HUF) time zone: CET (GMT +1) international students on 750 foreign climate: dry continental with four seasons language study programmes in 39 HEIs language: Hungarian HUNGARIAN HIGHER EDUCATION ACCORDING BASIC STRUCTURE OF STUDY PROGRAMMES TO INTERNATIONAL STUDENTS BA / BSc MA / MSc Doctoral (PhD, DLA) (6-8 semester) (2-4 semester) (8 semester) THE TOP 3 REASONS FOR STUDYING IN HUNGARY: HIGH QUALITY OF (10-12 semester) EDUCATION, GETTING TO KNOW ANOTHER CULTURE AND AFFORDABLE PRICES. -

Certain Aspects of Family Policy Incentives for Childbearing—A Hungarian Study with an International Outlook

sustainability Article Certain Aspects of Family Policy Incentives for Childbearing—A Hungarian Study with an International Outlook Judit Sági 1,* and Csaba Lentner 2,* 1 Budapest Business School, University of Applied Sciences, H-1149 Budapest, Hungary 2 National University of Public Service, H-1083 Budapest, Hungary * Correspondence: [email protected] (J.S.); [email protected] (C.L.); Tel.: +36-30-2211408 (J.S.); +36-70-2877728 (C.L.) Received: 7 September 2018; Accepted: 29 October 2018; Published: 31 October 2018 Abstract: Decreasing trends in birth rates in developed countries during the past decades, which threaten the sustainability of their populations, raise concerns in the areas of employment and social security, among others. A decrease in willingness to bear children has been examined in the international literature from several (biological, socio-cultural, economic, and spatial, etc.) aspects. Among these, the question of the effectiveness of fiscal incentives has been raised, with arguments that these are positive, but not significant, to birth rates; our study also concludes this. In Hungary, from 2010 onwards, the government has introduced very high tax allowances for families and, from 2015, has provided direct subsidies for housing purposes, all within a framework of a new family policy regime. This paper presents an evaluation of family policy interventions (e.g., housing support, tax allowances, other child-raising benefits), with the conclusion that fiscal incentives cannot be effective by themselves; a sustainable level of birth rates can only be maintained, but not necessarily increased, with an optimal design of family policy incentives. By studying the Hungarian example of pro-birth policies there is shown to be a policy gap in housing subsidies.