Praise for Manu Saadia

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Challenge #4: Mission Accomplished “Design a Mission.”

Challenge #4: Mission Accomplished “Design a mission.” In this challenge, the contestants were asked to design a mission with a special focus on making a Maquis or terrorism themed mission. The winning card would earn the chance to be play tested in Project Boomer, the upcoming expansion centered around the Maquis. Mission design can be difficult because of the wildly fluctuating standards of what makes a mission “good,” and the extremely limited amount of space on the template. How did our contestants do in their attempts to make playable missions? And which mission will end up in testing for Boomer? This document contains the results from this challenge, as well as all of the comments and feedback provided during the judging. Design Credits Here is a list of the cards, their designers, and the scores for Challenge #4: Card Designer Public Allen Dan Total Vote Gould Hamman Score Ambush Maquis Chewie 6.00 5 6 17.00 Exchange Military Hardware KazonPADD 6.17 5 7.5 18.67 Intercept Convoy Comicbookhero 6.88 7 7.5 21.38 Interrogate Kidnapped Prisoner Orbin 6.70 8 7 21.70 Organize Terrorist Attacks Jono 6.65 5 5 16.65 Recruit Militants Verad 5.26 5 5 15.26 Scrape By BCSWowbagger 7.33 7 7 21.33 Seek Refuge Zef’no 6.88 7 7.5 21.38 No Submission Dogbert ---- ---- ---- ---- Leaderboard After one (4) challenges, here are the standings in Make it So 2013: Place Contestant Forum Name Challenge #4 Total Score 1 (NC) Stephen G. Zef’no 21.38 96.33 2 (NC) James Monsebroten Orbin 21.70 92.13 3 (NC) Adam Hegarty Chewie 17.00 84.56 4 (NC) Michael Moskop Comicbookhero 21.38 83.63 5 (NC) Sean O’Reilly Jono 16.65 78.36 6 (+1) Paddy Tye KazonPADD 18.67 77.23 7 (+1) James Heaney BCSWowbagger 21.33 77.21 8 (-2) Philip H. -

TRADING CARDS 2016 STAR TREK 50Th ANNIVERSARY

2016 STAR TREK 50 th ANNIVERSARY TRADING CARDS 1995-96 30 Years of Star Trek 1995-96 30 Years of Star Trek Registry Plaques A6b James Doohan (Lt. Arex) 50.00 100.00 A7 Dorothy Fontana 15.00 40.00 COMPLETE SET (9) 100.00 200.00 COMMON CARD (R1-R9) 12.00 30.00 STATED ODDS 1:72 2003 Complete Star Trek Animated Adventures INSERTED INTO PHASE ONE PACKS Captain Kirk in Motion COMPLETE SET (9) 12.50 30.00 1995-96 30 Years of Star Trek Space Mural Foil COMMON CARD (K1-K9) 1.50 4.00 COMPLETE SET (9) 25.00 60.00 STATED ODDS 1:20 COMMON CARD (S1-S9) 4.00 10.00 STATED ODDS 1:12 2003 Complete Star Trek Animated Adventures Die- COMPLETE SET (300) 15.00 40.00 INSERTED INTO PHASE THREE PACKS Cut CD-ROMs PHASE ONE SET (100) 6.00 15.00 COMPLETE SET (5) 10.00 25.00 PHASE TWO SET (100) 6.00 15.00 1995-96 30 Years of Star Trek Undercover PHASE THREE SET (100) 6.00 15.00 COMMON CARD 2.50 6.00 COMPLETE SET (9) 50.00 100.00 STATED ODDS 1:BOX UNOPENED PH.ONE BOX (36 PACKS) 40.00 50.00 COMMON CARD (L1-L9) 6.00 15.00 UNNUMBERED SET UNOPENED PH.ONE PACK (8 CARDS) 1.25 1.50 STATED ODDS 1:18 UNOPENED PH.TWO BOX (36 PACKS) 40.00 50.00 INSERTED INTO PHASE TWO PACKS UNOPENED PH.TWO PACK (8 CARDS) 1.25 1.50 2003 Complete Star Trek Animated Adventures James Doohan Tribute UNOPENED PH.THREE BOX (36 PACKS) 40.00 50.00 1995-96 30 Years of Star Trek Promos UNOPENED PH.THREE PACK (8 CARDS) 1.25 1.50 COMPLETE SET (9) 2.50 6.00 PROMOS ARE UNNUMBERED COMMON CARD (JD1-JD9) .40 1.00 PHASE ONE (1-100) .12 .30 1 NCC-1701, tricorder; 2-card panel STATED ODDS 1:4 PHASE TWO (101-200) -

Science Fiction Review 37

SCIENCE FICTION REVIEW $2.00 WINTER 1980 NUMBER 37 SCIENCE FICTION REVIEW (ISSN: 0036-8377) Formerly THE ALIEN CRITZ® P.O. BOX 11408 NOVEMBER 1980 — VOL.9, NO .4 PORTLAND, OR 97211 WHOLE NUMBER 37 PHONE: (503) 282-0381 RICHARD E. GEIS, editor & publisher PAULETTE MINARE', ASSOCIATE EDITOR PUBLISHED QUARTERLY FEB., MAY, AUG., NOV. SINGLE COPY — $2.00 COVER BY STEPHEN FABIAN SHORT FICTION REVIEWS "PET" ANALOG—PATRICIA MATHEWS.40 ASIMOV'S-ROBERT SABELLA.42 F8SF-RUSSELL ENGEBRETSON.43 ALIEN THOUGHTS DESTINIES-PATRICIA MATHEWS.44 GALAXY-JAFtS J.J, WILSON.44 REVIEWS- BY THE EDITOR.A OTT4I-MARGANA B. ROLAIN.45 PLAYBOY-H.H. EDWARD FORGIE.47 BATTLE BEYOND THE STARS. THE MAN WITH THE COSMIC ORIGINAL ANTHOLOGIES —DAVID A. , _ TTE HUNTER..... TRUESDALE...47 ESCAPE FROM ALCATRAZ. TRIGGERFINGER—an interview with JUST YOU AND Ft, KID. ROBERT ANTON WILSON SMALL PRESS NOTES THE ELECTRIC HORSEMAN. CONDUCTED BY NEAL WILGUS.. .6 BY THE EDITOR.49 THE CHILDREN. THE ORPHAN. ZOMBIE. AND THEN I SAW.... LETTERS.51 THE HILLS HAVE EYES. BY THE EDITOR.10 FROM BUZZ DIXON THE OCTOGON. TOM STAICAR THE BIG BRAWL. MARK J. MCGARRY INTERFACES. "WE'RE COMING THROUGH THE WINDOW" ORSON SCOTT CARD THE EDGE OF RUNNING WATER. ELTON T. ELLIOTT SF WRITER S WORKSHOP I. LETTER, INTRODUCTION AND STORY NEVILLE J. ANGOVE BY BARRY N. MALZBERG.12 AN HOUR WITH HARLAN ELLISON.... JOHN SHIRLEY AN HOUR WITH ISAAC ASIMOV. ROBERT BLOCH CITY.. GENE WOLFE TIC DEAD ZONE. THE VIVISECTOR CHARLES R. SAUNDERS BY DARRELL SCHWEITZER.15 FRANK FRAZETTA, BOOK FOUR.24 ALEXIS GILLILAND Tl-E LAST IMMORTAL.24 ROBERT A.W, LOWNDES DARK IS THE SUN.24 LARRY NIVEN TFC MAN IN THE DARKSUIT.24 INSIDE THE WHALE RONALD R. -

DEEP SPACE NINE® on DVD

Star Trek: DEEP SPACE NINE® on DVD Prod. Season/ Box/ Prod. Season/ Box/ Title Title # Year Disc # Year Disc Abandoned, The 452 3/1994 3/2 Emissary, Part I 401 1/1993 721 1/1 Accession 489 4/1996 4/5 Emissary, Part II 402 1/1993 Adversary, The 472 3/1995 3/7 Emperor's New Cloak, The 562 7/1999 7/3 Afterimage 553 7/1998 7/1 Empok Nor 522 5/1997 5/6 Alternate, The 432 2/1994 2/3 Equilibrium 450 3/1994 3/1 Apocalypse Rising 499 5/1996 5/1 Explorers 468 3/1995 3/6 Armageddon Game 433 2/1994 2/4 Extreme Measures 573 7/1999 7/6 Ascent, The 507 5/1996 5/3 Facets 471 3/1995 3/7 Assignment, The 504 5/1996 5/2 Family Business 469 3/1995 3/6 Babel 405 1/1993 1/2 Far Beyond the Stars 538 6/1998 6/4 Badda-Bing, Badda-Bang 566 7/1999 7/4 Fascination 456 3/1994 3/3 Bar Association 488 4/1996 4/4 Favor the Bold 529 6/1997 6/2 Battle Lines 413 1/1993 1/4 Ferengi Love Songs 518 5/1997 5/5 Begotten, The 510 5/1997 5/3 Field of Fire 563 7/1999 7/4 Behind the Lines 528 6/1997 6/1 For the Cause 494 4/1996 4/6 Blaze of Glory 521 5/1997 5/6 For the Uniform 511 5/1997 5/4 Blood Oath 439 2/1994 2/5 Forsaken, The 417 1/1993 1/5 Body Parts 497 4/1996 4/7 Hard Time 491 4/1996 4/5 Broken Link 498 4/1996 4/7 Heart of Stone 460 3/1995 3/4 Business as Usual 516 5/1997 5/5 Hippocratic Oath 475 4/1995 4/1 By Inferno's Light 513 5/1997 5/4 His Way 544 6/1998 6/5 Call to Arms 524 5/1997 5/7 Homecoming, The 421 2/1993 2/1 Captive Pursuit 406 1/1993 1/2 Homefront 483 4/1996 4/3 Cardassians 425 2/1993 2/2 Honor Among Thieves 539 6/1998 6/4 Change of Heart 540 6/1998 6/4 House -

Star Trek Episodeguide Lcars-Online.De 2

LCARS-ONLINE.DE STAR TREK EPISODEGUIDE LCARS-ONLINE.DE 2 STAR TREK: THE ORIGINAL SERIES 1 2 3 STAR TREK: THE NEXT GENERATION 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 STAR TREK: DEEP SPACE NINE 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 STAR TREK: VOYAGER 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 STAR TREK: ENTERPRISE 1 2 3 4 LCARS-ONLINE.DE 3 PILOTFOLGE Nr. DEUTSCH ENGLISCH 0x00 Der Käfig The Cage 1. STAFFEL Nr. DEUTSCH ENGLISCH 1x01 Das Letzte seiner Art The Man Trap 1x02 Der Fall Charlie Charlie X 1x03 Spitze des Eisbergs Where No Man Has Gone Before 1x04 Implosion in der Spirale The Naked Time 1x05 Kirk : 2 = ? The Enemy Within 1x06 Die Frauen des Mr. Mudd Mudd‘s Women 1x07 Der alte Traum What Are Little Girls Made Of? 1x08 Miri, ein Kleinling Miri 1x09 Der Zentralnervensystemmanipulator Dagger of the Mind 1x10 Pokerspiele The Corbomite Maneuver 1x11 Talos IV – Tabu, Teil 1 The Menagerie, Part I 1x12 Talos IV – Tabu, Teil 2 The Menagerie, Part II 1x13 Kodos, der Henker The Consience of the King 1x14 Spock unter Verdacht Balance of Terror 1x15 Landeurlaub Shore Leave 1x16 Notlandung auf Galileo 7 The Galileo Seven 1x17 Tödliche Spiele auf Gothos The Squire of Gothos 1x18 Ganz neue Dimensionen Arena 1x19 Morgen ist Gestern Tomorrow Is Yesterday 1x20 Kirk unter Anklage Court Martial LCARS-ONLINE.DE 4 1. STAFFEL (FORTSETZUNG) Nr. DEUTSCH ENGLISCH 1x21 Landru und die Ewigkeit The Return of the Archons 1x22 Der schlafende Tiger Space Seed 1x23 Krieg der Computer A Taste of Armageddon 1x24 Falsche Paradiese This Side of Paradise 1x25 Horta rettet ihre Kinder The Devil in the Dark 1x26 Kampf um Organia Errand of Mercy 1x27 Auf Messers Schneide The Alternative Factor 1x28 Griff in die Geschichte The City on the Edge of Forever 1x29 Spock außer Kontrolle Operation: Annihilate! LCARS-ONLINE.DE 5 2. -

Philosophy Looks at Chess 5/27/08 1:47 PM Page I

Philosophy Looks at Chess 5/27/08 1:47 PM Page i Philosophy Looks at Chess Philosophy Looks at Chess 5/27/08 1:47 PM Page iii Philosophy Looks at Chess Edited by BENJAMIN HALE OPEN COURT Chicago and La Salle, Illinois Philosophy Looks at Chess 5/27/08 1:47 PM Page iv To order books from Open Court, call 1-800-815-2280, or visit our website at www.opencourtbooks.com. Open Court Publishing Company is a division of Carus Publishing Company. Copyright © 2008 by Carus Publishing Company First printing 2008 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the publisher, Open Court Publishing Company, a division of Carus Publishing Company, 315 Fifth Street, P.O. Box 300, Peru, Illinois, 61354. Printed and bound in the United States of America. n: Joan Som Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Pink Floyd and philosophy : careful with that axiom, Eugene! / edited by George A. Reisch. p. cm. — (Popular culture and philosophy) Summary: “Essays critically examine philosophical concepts and problems in the music and lyrics of the band Pink Floyd” — Provided by publisher. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN-13: 978-0-8126-9636-3 (trade pbk. : alk. paper) ISBN-10: 0-8126-9636-0 (trade pbk. : alk. paper) 1. Pink Floyd (Musical group) 2. Rock music—History and criticism 3. Music—Philosophy and aesthetics. I. Reisch, George A., 1962- ML421.P6P54 2007 Philosophy Looks at Chess 5/27/08 1:47 PM Page v Contents Introduction 00 1. -

CHALLENGER No

CHALLENGER no. 38 Guy & Rosy Lillian, editors Autumn, 2014 1390 Holly Avenue Merritt Island FL 32952 [email protected] Cover by AL SIROIS CONTENTS 1 Editorial: what Future?/Contraflow GHLIII 2 Our Old Future Gregory Benford 5 “I Never Repeat a Joke …” Joseph Major 9 The Challenger Tribute: JoAnn Montalbano GHLIII (Art by Charlie Williams) 13 The Predictions of Jules Verne / The Predictions of H.G. Wells Joseph L. Green 14 The Infamous Baycon Mike Resnick (Art by Kurt Erichsen) 20 A Marvelous House GHLIII (Photos by Guy & Rosy Lillian) 23 A Brief (Cinematic) History of the Future Jim Ivers 26 The Chorus Lines everyone 39 Afoot at Loncon … Gregory Benford 51 Zeppelin Terror W. Jas. Wentz (Illustration by Taral Wayne) 55 Chicon 7 Guest of Honor Speech Mike Resnick 62 Poem David Thayer 76 “We are all interested in the future, because that is where we are going to spend the rest of our lives.” Criswell, Plan 9 from Outer Space Challenger no. 38 is © 2014 by Guy H. Lillian III. All rights to original creators; reprint rights retained. GHLIII Press Publication #1160. what FUTURE? Fifty years ago, as a blushing youth of 14, I read the first volume of The Hugo Winners – a series I fervently wish some publisher would revive. Within, no less an authority than Isaac Asimov heaped praise on a novel originally published in 1939, Sinister Barrier by Erik Frank Russell. In subsequent years I never got around to reading the book until, aground in Florida in forced retirement, I thought to correct this lifelong lapse and ordered a cheap reading copy from eBay. -

Star Trek Fan Community

The Effect of Commercialisation and Direct Intervention by the Owners of Intellectual Copyright A Case Study: The Australian Star Trek Fan Community Susan Pamela Batho PhD Candidate University of Western Sydney Australia 2009 Resubmitted March 2009 © Susan Batho February 2007 Statement of Authentication The work presented in this thesis is, to the best of my knowledge and belief, original except as acknowledged in the text. I hereby declare that I have not submitted this material, either in full or in part, for a degree at this or any other institution. …………………………………………… (Signature) ABSTRACT In the early 1990s, Australian Star Trek fandom appeared to be thriving, with large numbers of members in individual clubs, many publications being produced and conventions being held. The Star Trek phenomenon was also growing, with its profitability being an attractive selling point. In 1994, Viacom purchased Paramount Communications, and expanded the control over its rights by offering licences to the title of Official Star Trek Club for countries outside of the United States, as well licences for numerous commercially sold items At the time they were in negotiation with the Microsoft Corporation to establish an on-line community space for Star Trek to attract the expanding internet fan presence, and relaunching Simon & Schuster’s Pocket Books which was part of Paramount Communications, as its sole source of Star Trek fiction, and had organised to launch the Star Trek Omnipedia, a CD produced by Simon & Schuster Interactive. A new Star Trek series, Voyager, was about to appear, and marketing-wise, it was a good time to expand their presence commercially, launch the new website, and organise the fans through Official Star Trek Clubs, feeding them new merchandise, and the new website. -

Star Trek and Gene Roddenberry's “Vision of the Future”: the Creation of an Early Television Auteur

Volume 5, Issue 2 September 2012 Star Trek and Gene Roddenberry’s “Vision of the Future”: The Creation of an Early Television Auteur MICHAEL KMET, University of California Los Angeles ABSTRACT Gene Roddenberry propagated a narrative of himself as a “visionary” writer-producer and the primary author of Star Trek in the 1960s. From the 1970s onwards, Paramount Pictures (and later, CBS) co-opted that narrative to market what would become the Star Trek franchise. This paper will examine to what extent this narrative can be substantiated, and to what extent certain aspects can be contested. KEYWORDS Authorship, auteur, Gene Roddenberry, Science Fiction, Star Trek. Telefantasy, Television, visionary. Introduction When Gene Roddenberry died on October 24, 1991, obituary writers frequently mentioned the “vision of the future” presented in Star Trek (1966-1969) and Star Trek: The Next Generation (1987-1994), the two longest-running television programs to credit Roddenberry as their creator1 (Roush, 1991; Anon., 1991, October 25). Some went even further, proclaiming the late writer-producer an outright ‘visionary, a man who created a cultural phenomenon’ (Anon., 1991, October 26). These were not new labels for Gene Roddenberry, who had been described in such lofty terms since he began attending Star Trek conventions in the early 1970s (Engel, 1994, p.142). In the two decades since Roddenberry’s death, similar descriptions of the writer-producer have continued to appear in Star Trek-related press coverage (Thompson, 1996), value-added content on home video, and nonfiction books (Greenwald, 1998). Although a few books and articles have been written since Roddenberry’s death that have questioned some of his more grandiose claims about Star Trek, many more have perpetuated them, and few have deviated from the narrative of Gene Roddenberry as visionary. -

Star Trek: the Packet

"Star Trek: The Packet" (1 TTGTlI v.4.11: None More Black Written by Rick Berman and Michael Piller (Mike Witry of the University ofIowa) Subject: Based upon Gene Roddenberry's "Star Trek" Tossups Tl. She kidnapped Geordi La Forge in an attempt to brainwash him into assassinating Klingon governor Vagh(*). Despite her failure, she went on to bigger and better things, like sneaking supplies to the Duras faction in the Klingon civil war, and trying to invade Vulcan under the guise of a peace initiative. FTP, name this only blonde Romulan, who, through a bizarre series of events, was the daughter ofTasha Yar. C Sela~ T2. These useful devices are connected directly into a circuit, and come in a variety of sizes, ranging from about one amp in a car(*) to 30 amps in small appliances and higher. Common in the 20th century, the technology to build them was evidently lost by the 23rd, as shown by the shower of sparks thrown out by the computer systems every time the ship is shot. FTP, name these electrical devices, which melt to prevent wires from overheating. CFuse~ T3. Once upon a time, the eccentric shopkeeper Obe noticed that a weary traveler, Greb, overpaid him for a canister of beetle snuff(*). He set out to Greb's hometown to make restitution, but when he was halfway there, he was murdered by assassins hired by none other than Greb, who had been carrying on an affair with Obe's wife. This parable inspired, FTP, which Ferengi Rule of Acquisition, which reads, "Once you have their money, you never give it back"? CFirst_ Rule of Acquisition) T4. -

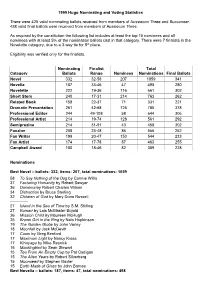

1999 Hugo Nominating and Voting Statistics There Were 425 Valid

1999 Hugo Nominating and Voting Statistics There were 425 valid nominating ballots received from members of Aussiecon Three and Bucconeer. 438 valid final ballots were received from members of Aussiecon Three. As required by the constitution the following list includes at least the top 15 nominees and all nominees with at least 5% of the nomination ballots cast in that category. There were 7 finalists in the Novelette category, due to a 3-way tie for 5th place. Eligibility was verified only for the finalists. Nominating Finalist Total Category Ballots Range Nominees Nominations Final Ballots Novel 332 32-58 207 1059 341 Novella 187 33-46 47 498 280 Novelette 222 19-36 116 661 302 Short Story 240 17-31 214 763 262 Related Book 159 22-37 71 331 221 Dramatic Presentation 261 42-68 125 785 378 Professional Editor 244 49-108 58 644 306 Professional Artist 214 19-74 128 561 292 Semiprozine 214 31-91 40 458 302 Fanzine 208 23-48 86 566 252 Fan Writer 199 20-47 153 544 233 Fan Artist 174 17-78 87 463 255 Campbell Award 180 18-46 82 389 228 Nominations Best Novel – ballots: 332, items: 207, total nominations: 1059 58 To Say Nothing of the Dog by Connie Willis 37 Factoring Humanity by Robert Sawyer 36 Darwinia by Robert Charles Wilson 34 Distraction by Bruce Sterling 32 Children of God by Mary Doria Russell ------------- 27 Island in the Sea of Time by S.M. Stirling 27 Komarr by Lois McMaster Bujold 26 Mission Child by Maureen McHugh 25 Brown Girl in the Ring by Nalo Hopkinson 19 The Golden Globe by John Varley 18 Moonfall by Jack McDevitt 17 Cosm -

Deep Space Nine Als Soziopolitische Fiktion Und Unvollendetes Projekt

Christoph Büttner Deep Space Nine als soziopolitische Fiktion und unvollendetes Projekt 1 Star Trek als soziopolitische Fiktion Zu dramatischer Musik laufen Captain Sisko und Major Kira durch die Gänge von Deep Space Nine, die Phasergewehre im Anschlag. Die Besatzung der Station ist auf der Suche nach einem Eindringling. Auf der Promenade kann der Stationsarzt Doktor Bashir noch einige Befehle an die Mannschaft erteilen, bevor er schließlich vom Gejagten überrascht wird. Die Situation, die sich als Übung herausstellt, wird in einer Art comic relief unterbrochen, als der Bartender Quark sich beschwert, dass die Übung seine Gäste verschrecke.1 Kurz darauf muss Captain Sisko eine Verabre- dung mit seiner Freundin unterbrechen, da die Mannschaften zahlreicher klingo- nischer Raumschiffe an Bord der Raumstation kommen. Schon in dieser kurzen Sequenz, den ersten zehn Minuten der Star Trek – Deep Space Nine (USA 1993–1999, Idee: Rick Berman, Michael Piller)-Episode «The Way of the Warrior» (S04/E01, 1995, R: James L. Conway) zeigt sich das Zusammenspiel ver- schiedener filmischer Verfahren zur Repräsentation unterschiedlicher sozialer Kon- figurationen und soziologischer Konzepte: Die Differenz zwischen Übung und realer Gefechtssituation etwa wird dadurch, dass sie erst verzögert aufgelöst wird, als kon- textuell abhängig von sozialen Bedeutungszuschreibungen2 begreiflich; die Figur Bas- hirs agiert in verschiedenen sozialen Rollen als Soldat, Arzt oder Freund; die Raum- station selbst als soziale Einheit besteht wiederum aus kleineren sozialen Einheiten (z. B. Paarbeziehungen), ist allerdings eingebettet in größere soziale Zusammenhänge und außerdem offen für den Austausch mit anderen sozialen Gebilden. Insofern sich in diesen unterschiedlichen sozialen Einheiten und Modi auch verschiedene (norma- tive) Ideen über soziale Konfigurationen ausdrücken, lässt sich Star Trek als Verhand- lung «soziopolitische[r] Fiktionen oder social-science-fiction»3 verstehen.