The Enlightenment Mariners and Transatlanticism of Star Trek

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Squeaky Wheels of New Zealand Cinema Brenda Allen* in Two Recent

The Man Alone, the Black Sheep and the Bad Apple: Squeaky Wheels of New Zealand Cinema Brenda Allen* In two recent New Zealand films, Black Sheep (Jonathan King, 2006) and Eagle vs Shark (Taika Waititi, 2007), the now passé trope of the Man Alone is framed as a squeaky wheel in love with its own malfunction. In King’s horror-comedy, a reluctant hero, Henry, who is pathologically afraid of sheep, fights his older brother Angus, a mutant were-sheep, with the assistance of his eco-activist love interest, Experience. By the end of the adventure Henry, a de facto city boy, reconciles with the land of his settler forebears. Waititi’s romantic comedy presents a self-absorbed and unromantic hero, Jarrod, who struggles to shine in the shadow of his deceased brother, Gordon. Jarrod and his dysfunctional father, Jonah, find themselves and each other through the supportive example and family values of love interest Lily. In both films the heroes begin as dysfunctional “men alone” and female characters, together with renewed contact with the land of their family homes, prove crucial to their catharsis, an outcome that is often missing in more traditional treatments of the trope. The strategy for recuperating these men alone involves Antipodean Camp, a style of humour identified by Nick Perry in 1998 and characterised by excess, reversal and parody. Perhaps because they come almost a decade later, Eagle vs Shark and Black Sheep do not encode the “genuflections to European taste” Perry notes in his examples, and, unlike those films, Black Sheep and Eagle vs Shark are self-aware enough to play on double meanings that point to “any idea of culture, including a national culture, as artifice” (Perry 14). -

Greatestgentour.Com Now to See a Live Podcast That's the Exact Opposite of This

Note: This show periodically replaces their ad breaks with new promotional clips. Because of this, both the transcription for the clips and the timestamps after them may be inaccurate at the time of viewing this transcript. 00:00:00 Ben Harrison Promo The following is a message from Uxbridge-Shimoda LLC. 00:00:02 Sound Effect Sound Effect [Computer beeps.] 00:00:03 Music Music Fun, jazzy background music. 00:00:04 Adam Promo Have you been the victim of a bad live podcast experience? Has this Pranica ever happened to you? You bought a ticket to your favorite live podcast, and when you get there, there aren't any seats for you, so you have to sit in the bathroom because the toilet is the only unoccupied seat? And because the sounds of flushing and people having diarrhea, you can just barely hear the sound of laughter? But it's not the kind of laughter where you can tell the podcast hosts are doing well. It's the kind of laughter where you know the hosts are eating shit. 00:00:31 Adam Promo And when the show is over and you wipe yourself off, there isn't any toilet paper. So you use your underwear and try to flush those down the toilet. But the toilet gets clogged on all your underwear, and giant dookies you spent 90 minutes making, and starts overflowing, so you just leave it there and go out to the meet and greet. But you aren't feeling normal, because you aren't wearing underwear, because you're feeling the inside of your pants in a way you've never felt before, so you're awkward in your own body. -

Star Trek and Religion

Star Trek and Religion: Changing attitudes towards religion Changingin Voyagerattitudes towardsand DS9 religion in Voyager and DS9 Star Trek: Deep Space Nine • Differences between DS9 and other Trek series: – Takes place on space station (repeated contact with different species, not just per- episode contact… deeper cultural understanding? – Religion central to premise, multiple episodes – Regular worship events featured: prayers, temple attendance, meditation, religious hierarchy, etc. Star Trek: Deep Space Nine • Does DS9 as a series respect religion? What factors might indicate that it does respect religion? What factors might indicate it does not? • Were we more open to the spiritual in the late 1990’s then we were in the 1980's (or 1960's), or less so? • Is “respect” another way of saying “patronizing rejection”? Star Trek: Deep Space Nine • Sisko’s “divine parentage”:revealed in Season Seven, Sisko’s mother was human, possessed by Bajoran Prophet – Mother left after Sisko born - mission accomplished! – Sisko is therefore sort-of, in a sci-fi way, of divine parentage - brought to life deliberately by beings worshipped as Gods. – First time ever “gods” are shown to act outside the species to whom they are sacred • What does this say about Star Trek: DS9’s treatment of the divine? Is this a more sympathetic treatment than Classic Trek or Next Gen? Star Trek: Deep Space Nine • Sisko’s Journey – Identified as the Emissary by spiritual leader of Bajor in pilot episode (“Emissary” 1993) – Religious role accepted reluctantly, but only as subordinate to Starfleet secular way of understanding (“Destiny” 1995; “Accession” 1996) – Truly accepts his religious role in fifth season - (“Rapture” 1997) Star Trek: Deep Space Nine • Sisko’s Journey, con’t – Starfleet role and Emissary role come into conflict in sixth season - Sisko chooses Starfleet role, and disaster follows (“Tears of the Prophets” 1998) – Season seven (final season) - Sisko follows spiritual path, fulfils destiny - religious journey compete. -

Super! Drama TV August 2020

Super! drama TV August 2020 Note: #=serial number [J]=in Japanese 2020.08.01 2020.08.02 Sat Sun 06:00 06:00 06:00 STAR TREK: DEEP SPACE NINE 06:00 STAR TREK: DEEP SPACE NINE 06:00 Season 5 Season 5 #10 #11 06:30 06:30 「RAPTURE」 「THE DARKNESS AND THE LIGHT」 06:30 07:00 07:00 07:00 CAPTAIN SCARLET AND THE 07:00 STAR TREK: THE NEXT 07:00 MYSTERONS GENERATION Season 6 #19 「DANGEROUS RENDEZVOUS」 #5 「SCHISMS」 07:30 07:30 07:30 JOE 90 07:30 #19 「LONE-HANDED 90」 08:00 08:00 08:00 ULTRAMAN TOWARDS THE 08:00 STAR TREK: THE NEXT 08:00 FUTURE [J] GENERATION Season 6 #2 「the hibernator」 #6 08:30 08:30 08:30 THUNDERBIRDS ARE GO Season 「TRUE Q」 08:30 3 #1 「'CHAOS' Part One」 09:00 09:00 09:00 information [J] 09:00 information [J] 09:00 09:30 09:30 09:30 NCIS: NEW ORLEANS Season 5 09:30 S.W.A.T. Season 3 09:30 #15 #6 「Crab Mentality」 「KINGDOM」 10:00 10:00 10:00 10:30 10:30 10:30 NCIS: NEW ORLEANS Season 5 10:30 DESIGNATED SURVIVOR Season 10:30 #16 2 「Survivor」 #12 11:00 11:00 「The Final Frontier」 11:00 11:30 11:30 11:30 information [J] 11:30 information [J] 11:30 12:00 12:00 12:00 NCIS Season 9 12:00 NCIS Season 9 12:00 #13 #19 「A Desperate Man」 「The Good Son」 12:30 12:30 12:30 13:00 13:00 13:00 NCIS Season 9 13:00 NCIS Season 9 13:00 #14 #20 「Life Before His Eyes」 「The Missionary Position」 13:30 13:30 13:30 14:00 14:00 14:00 NCIS Season 9 14:00 NCIS Season 9 14:00 #15 #21 「Secrets」 「Rekindled」 14:30 14:30 14:30 15:00 15:00 15:00 NCIS Season 9 15:00 NCIS Season 9 15:00 #16 #22 「Psych out」 「Playing with Fire」 15:30 15:30 15:30 16:00 16:00 16:00 NCIS Season 9 16:00 NCIS Season 9 16:00 #17 #23 「Need to Know」 「Up in Smoke」 16:30 16:30 16:30 17:00 17:00 17:00 NCIS Season 9 17:00 NCIS Season 9 17:00 #18 #24 「The Tell」 「Till Death Do Us Part」 17:30 17:30 17:30 18:00 18:00 18:00 MACGYVER Season 2 [J] 18:00 THE MYSTERIES OF LAURA 18:00 #9 Season 1 「CD-ROM + Hoagie Foil」 #19 18:30 18:30 「The Mystery of the Dodgy Draft」 18:30 19:00 19:00 19:00 information [J] 19:00 THE BLACKLIST Season 7 19:00 #14 「TWAMIE ULLULAQ (NO. -

Star Trek" Mary Jo Deegan University of Nebraska-Lincoln, [email protected]

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by UNL | Libraries University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Sociology Department, Faculty Publications Sociology, Department of 1986 Sexism in Space: The rF eudian Formula in "Star Trek" Mary Jo Deegan University of Nebraska-Lincoln, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/sociologyfacpub Part of the Family, Life Course, and Society Commons, and the Social Psychology and Interaction Commons Deegan, Mary Jo, "Sexism in Space: The rF eudian Formula in "Star Trek"" (1986). Sociology Department, Faculty Publications. 368. http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/sociologyfacpub/368 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Sociology, Department of at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Sociology Department, Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. THIS FILE CONTAINS THE FOLLOWING MATERIALS: Deegan, Mary Jo. 1986. “Sexism in Space: The Freudian Formula in ‘Star Trek.’” Pp. 209-224 in Eros in the Mind’s Eye: Sexuality and the Fantastic in Art and Film, edited by Donald Palumbo. (Contributions to the Study of Science Fiction and Fantasy, No. 21). New York: Greenwood Press. 17 Sexism in Space: The Freudian Formula in IIStar Trek" MARY JO DEEGAN Space, the final frontier. These are the voyages of the starship Enterprise, its five year mission to explore strange new worlds, to seek out new life and new civilizations, to boldly go where no man has gone before. These words, spoken at the beginning of each televised "Star Trek" episode, set the stage for the fan tastic future. -

The Passing of the Mythicized Frontier Father Figure and Its Effect on The

Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Retrospective Theses and Dissertations Dissertations 1991 The ap ssing of the mythicized frontier father figure and its effect on the son in Larry McMurtry's Horseman, Pass By Julie Marie Walbridge Iowa State University Follow this and additional works at: https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/rtd Part of the American Literature Commons, and the Literature in English, North America Commons Recommended Citation Walbridge, Julie Marie, "The asp sing of the mythicized frontier father figure and its effect on the son in Larry McMurtry's Horseman, Pass By" (1991). Retrospective Theses and Dissertations. 66. https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/rtd/66 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Dissertations at Iowa State University Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Retrospective Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Iowa State University Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The passing of the mythicized frontier father figure and its effect on the son in Larry McMurtry's Horseman, Pass By by Julie Marie Walbridge A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS Department: English Major: English (Literature) Iowa State University Ames, Iowa 1991 ----------- ii TABLE OF CONTENTS Page INTRODUCTION 1 CHAPTER ONE 7 CHAPTER TWO 1 5 CONCLUSION 38 WORKS CITED 42 WORKS CONSULTED 44 -------- -------· ------------ 1 INTRODUCTION For this thesis the term "frontier" means more than the definition of having no more than two non-Indian settlers per square mile (Turner 3). -

___... -.:: GEOCITIES.Ws

__ __ _____ _____ _____ _____ ____ _ __ / / / / /_ _/ / ___/ /_ _/ / __ ) / _ \ | | / / / /__/ / / / ( ( / / / / / / / /_) / | |/ / / ___ / / / \ \ / / / / / / / _ _/ | _/ / / / / __/ / ____) ) / / / /_/ / / / \ \ / / /_/ /_/ /____/ /_____/ /_/ (_____/ /_/ /_/ /_/ _____ _____ _____ __ __ _____ / __ ) / ___/ /_ _/ / / / / / ___/ / / / / / /__ / / / /__/ / / /__ / / / / / ___/ / / / ___ / / ___/ / /_/ / / / / / / / / / / /___ (_____/ /_/ /_/ /_/ /_/ /_____/ _____ __ __ _____ __ __ ____ _____ / ___/ / / / / /_ _/ / / / / / _ \ / ___/ / /__ / / / / / / / / / / / /_) / / /__ / ___/ / / / / / / / / / / / _ _/ / ___/ / / / /_/ / / / / /_/ / / / \ \ / /___ /_/ (_____/ /_/ (_____/ /_/ /_/ /_____/ A TIMELINE OF THE MULTIVERSE Version 1.21 By K. Bradley Washburn "The Historian" ______________ | __ | | \| /\ / | | |/_/ / | | |\ \/\ / | | |_\/ \/ | |______________| K. Bradley Washburn HISTORY OF THE FUTURE Page 2 of 2 FOREWARD Relevant Notes WARNING: THIS FILE IS HAZARDOUS TO YOUR PRINTER'S INK SUPPLY!!! [*Story(Time Before:Time Transpired:Time After)] KEY TO ABBREVIATIONS AS--The Amazing Stories AST--Animated Star Trek B5--Babylon 5 BT--The Best of Trek DS9--Deep Space Nine EL--Enterprise Logs ENT--Enterprise LD--The Lives of Dax NE--New Earth NF--New Frontier RPG--Role-Playing Games S.C.E.--Starfleet Corps of Engineers SA--Starfleet Academy SNW--Strange New Worlds sQ--seaQuest ST--Star Trek TNG--The Next Generation TNV--The New Voyages V--Voyager WLB—Gateways: What Lay Beyond Blue italics - Completely canonical. Animated and live-action movies, episodes, and their novelizations. Green italics - Officially canonical. Novels, comics, and graphic novels. Red italics – Marginally canonical. Role-playing material, source books, internet sources. For more notes, see the AFTERWORD K. Bradley Washburn HISTORY OF THE FUTURE Page 3 of 3 TIMELINE circa 13.5 billion years ago * The Big Bang. -

Challenge #4: Mission Accomplished “Design a Mission.”

Challenge #4: Mission Accomplished “Design a mission.” In this challenge, the contestants were asked to design a mission with a special focus on making a Maquis or terrorism themed mission. The winning card would earn the chance to be play tested in Project Boomer, the upcoming expansion centered around the Maquis. Mission design can be difficult because of the wildly fluctuating standards of what makes a mission “good,” and the extremely limited amount of space on the template. How did our contestants do in their attempts to make playable missions? And which mission will end up in testing for Boomer? This document contains the results from this challenge, as well as all of the comments and feedback provided during the judging. Design Credits Here is a list of the cards, their designers, and the scores for Challenge #4: Card Designer Public Allen Dan Total Vote Gould Hamman Score Ambush Maquis Chewie 6.00 5 6 17.00 Exchange Military Hardware KazonPADD 6.17 5 7.5 18.67 Intercept Convoy Comicbookhero 6.88 7 7.5 21.38 Interrogate Kidnapped Prisoner Orbin 6.70 8 7 21.70 Organize Terrorist Attacks Jono 6.65 5 5 16.65 Recruit Militants Verad 5.26 5 5 15.26 Scrape By BCSWowbagger 7.33 7 7 21.33 Seek Refuge Zef’no 6.88 7 7.5 21.38 No Submission Dogbert ---- ---- ---- ---- Leaderboard After one (4) challenges, here are the standings in Make it So 2013: Place Contestant Forum Name Challenge #4 Total Score 1 (NC) Stephen G. Zef’no 21.38 96.33 2 (NC) James Monsebroten Orbin 21.70 92.13 3 (NC) Adam Hegarty Chewie 17.00 84.56 4 (NC) Michael Moskop Comicbookhero 21.38 83.63 5 (NC) Sean O’Reilly Jono 16.65 78.36 6 (+1) Paddy Tye KazonPADD 18.67 77.23 7 (+1) James Heaney BCSWowbagger 21.33 77.21 8 (-2) Philip H. -

Praise for Manu Saadia

PRAISE FOR MANU SAADIA “Manu Saadia proves that Star Trek is an even more valuable cultural icon than we ever suspected.” —Charlie Jane Anders, Hugo Award winner, editor in chief, io9 “In Trekonomics, Saadia reminds us of what made Star Trek such a bold experiment in the first place: its Utopian theme of human culture recovering from capitalism. Smart, funny, and wise, this book is a great work of analysis for fans of Star Trek and a call to arms for fans of eco- nomic justice.” —Annalee Newitz, tech culture editor, Ars Technica “To understand the fictional world of Star Trek is to understand not only the forces which drive our real world, but also the changes that are necessary to improve it. Manu’s book will change the way you see three different universes: the one that Gene Roddenberry created, the one we’re in, and the one we’re headed toward.” —Felix Salmon, senior editor, Fusion TREKONOMICS TREKONOMICS MANU SAADIA Copyright © 2016 Manu Saadia All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, or stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without express written permission of the publisher. Published by Pipertext Publishing Co., Inc., in association with Inkshares, Inc., San Francisco, California www.pipertext.com www.inkshares.com Edited and designed by Girl Friday Productions www.girlfridayproductions.com Cover design by Jennifer Bostic Cover art by John Powers ISBN: 9781941758755 e-ISBN: 9781941758762 Library of Congress Control Number: 2016931451 First edition Printed in United States To Lazare, our chief engineer, and to my father, Yossef Saadia. -

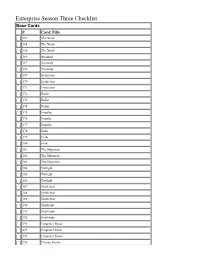

Enterprise Season Three Checklist

Enterprise Season Three Checklist Base Cards # Card Title [ ] 163 The Xindi [ ] 164 The Xindi [ ] 165 The Xindi [ ] 166 Anomaly [ ] 167 Anomaly [ ] 168 Anomaly [ ] 169 Extinction [ ] 170 Extinction [ ] 171 Extinction [ ] 172 Raijin [ ] 173 Raijin [ ] 174 Raijin [ ] 175 Impulse [ ] 176 Impulse [ ] 177 Impulse [ ] 178 Exile [ ] 179 Exile [ ] 180 Exile [ ] 181 The Shipment [ ] 182 The Shipment [ ] 183 The Shipment [ ] 184 Twilight [ ] 185 Twilight [ ] 186 Twilight [ ] 187 North Star [ ] 188 North Star [ ] 189 North Star [ ] 190 Similitude [ ] 191 Similitude [ ] 192 Similitude [ ] 193 Carpenter Street [ ] 194 Carpenter Street [ ] 195 Carpenter Street [ ] 196 Chosen Realm [ ] 197 Chosen Realm [ ] 198 Chosen Realm [ ] 199 Proving Ground [ ] 200 Proving Ground [ ] 201 Proving Ground [ ] 202 Stratagem [ ] 203 Stratagem [ ] 204 Stratagem [ ] 205 Harbinger [ ] 206 Harbinger [ ] 207 Harbinger [ ] 208 Doctor's Orders [ ] 209 Doctor's Orders [ ] 210 Doctor's Orders [ ] 211 Hatchery [ ] 212 Hatchery [ ] 213 Hatchery [ ] 214 Azati Prime [ ] 215 Azati Prime [ ] 216 Azati Prime [ ] 217 Damage [ ] 218 Damage [ ] 219 Damage [ ] 220 The Forgotten [ ] 221 The Forgotten [ ] 222 The Forgotten [ ] 223 E2 [ ] 224 E2 [ ] 225 E2 [ ] 226 The Council [ ] 227 The Council [ ] 228 The Council [ ] 229 Countdown [ ] 230 Countdown [ ] 231 Countdown [ ] 232 Zero Hour [ ] 233 Zero Hour [ ] 234 Zero Hour Checklist Cards (1:16 packs) # Card Title [ ] C1 Checklist 1 [ ] C2 Checklist 2 [ ] C3 Checklist 3 MACOs In Action (1:10 packs) # Card Title [ ] M1 Military Assault Command -

The XINDI CRISIS

Julian Wangler 1 Enterprise: AFTERMATH #1 2 Julian Wangler Julian Wangler The XINDI CRISIS A Transgression Dokumentsammlung Ω www.startrek-companion.de 3 Enterprise: AFTERMATH #1 Up until about 100 years ago, there was one question that burned in every human that made us study the stars and dream of traveling to them: “Are we alone?” Our generation is privileged to know the answer to that question. We are all explorers, driven to know what’s over the horizon, what’s beyond our own shores. And yet, the more I’ve experienced, the more I’ve learned that no matter how far we travel or how fast we get there, the most profound discoveries are not necessarily beyond that next star. They’re within us; woven into the threads that bind us, all of us, to each other. The Final Frontier begins in this hall. Let’s explore it together. – Jonathan Archer, 2155 © 2014 Julian Wangler STAR TREK is a Registred Trademark of Paramount Pictures/CBS Studios Inc. all rights reserved 4 Julian Wangler Am 4. April 2153 taucht unvermittelt ein un- bekanntes Flugobjekt im Erdorbit auf und feuert einen mächtigen Partikelstrahl ab. Dieser zieht eine Schneise von Florida bis Venezuela und tötet sieben Millionen Menschen. Lichtjahre entfernt erfährt Jonathan Archer vom Auftraggeber seines alten Widersachers Silik, dass die Xindi hinter dem Angriff auf die Erde stecken – eine Spezies, die in einer Region beheimatet ist, die gemeinhin als Delphische Ausdehnung bekannt ist. Offenbar wurden die Xindi davon überzeugt, dass die Menschheit sie in ferner Zukunft vernichten wird und haben deshalb beschlossen, präventiv zu handeln. -

Star Trek STAG NL 28 (STAG Newsletter 28).Pdf

/ April 1978 NEWSLETTER No. 28 President/Secretary, Janet Quarton, 15 Letter Daill, Cairnbaan, Lochgi Iphe ad , hrgyll, Sootland. Vioe PreSident/Editor, Sheila Clark, 6 Craigmill Cottages, Strathmartine, by Dundee, Sootland. Sales Seoretary' Beth Hallam, Flat 3, 36 Clapham Rd, Bedford, England. Membership Seoretary' Sylvia Billings, 49 Southampton Rd, Far Cotton, Northampton, England. Honorary Members> Gene Roddenberry, Mejel Barrett, William Shatner, James Doohan, George Takei, Susan Sackett, Anne MoCaffrey, 1,nne Page. ***************** DUES U.K. £1.50 per year. Europe £2 printed rate, £3.50 idrmail letter rate. U.S.A. ~6.00 l.irmail, ~4.00 surfaoe,' ],ustralia & J~pan, £3 airmail, £2 surface. ***************** Hi, there, I'm sorry this newsletter is a few days late out but I hope you agree that it was worth waiting so that we could give you the latest news from Paramount. It is great to hear, that the go-ahead has finally been given for the movie and that Leonard Nimoy will be back as Spock. SThR TREK just wouldn't have been the same without him. We don't know how things between Leonard and Paramount, etc, were eventually worked out, we are just happy to hear that they have been. 'jle sent out copies of the telegram we received from Gene on Maroh 28th to those of you who sent us S;.Es for info, as we weren't sure how long the newsletter would be delayed. ,Ie guessed you would hear ru:wurs and want confirmation as soon as possible. If any of you want important news as we receive it just send me an SAE and 1'11 file it for later use.