Star Trek Fan Community

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Utah for 2019 Nasfic

Warren Buff Site Selection Administrator, Worldcon 76 NASFiC 2019 voting @ Worldcon 76, San Jose, California, 12/18/2017 Dear Mr. Buff, Please find attached the documents announcing the Utah Fandom Organization’s bid to hold NASFiC in Layton, Utah on July 4th - 7th, 2019. This is our formal request under Article 4 of the WSFS constitution. Our proposed facility is the Davis Conference Center with the attached Hilton Garden Inn, as well as courtesy room blocks in overflow hotels provided through our Davis County Tourism & Events Board; documents also attached. Please note Layton, Utah is more than 500 miles from San Jose, California, to fulfill the mileage radius required by the constitution. You can find our extra details and enthusiasm at http://www.utahfor2019.com . I have also attached a full list of our Bid Team, as well as our Westercon 72 committee who jumps in to help all across the globe. Attached includes our UFO bylaws and articles of incorporation. If selected, we will operate as part of the standing committee established by UFO to operate Westercon 72. The Chair of the committee is selected by the President of the corporation and ratified by the Board of Directors. The Chair can be removed by a vote of an majority of the entire membership of the Board of Directors. Thank you for your consideration. We hope to do the Worldcon & NASFiC fan community proud. Kate Hatcher President of U.F.O Chair of Westercon 72 & Co Bid Chair of NASFiC 2019 [email protected] [email protected] Utahfor2019.com 12/18/17 NASFiC Bid -

To Sunday 31St August 2003

The World Science Fiction Society Minutes of the Business Meeting at Torcon 3 th Friday 29 to Sunday 31st August 2003 Introduction………………………………………………………………….… 3 Preliminary Business Meeting, Friday……………………………………… 4 Main Business Meeting, Saturday…………………………………………… 11 Main Business Meeting, Sunday……………………………………………… 16 Preliminary Business Meeting Agenda, Friday………………………………. 21 Report of the WSFS Nitpicking and Flyspecking Committee 27 FOLLE Report 33 LA con III Financial Report 48 LoneStarCon II Financial Report 50 BucConeer Financial Report 51 Chicon 2000 Financial Report 52 The Millennium Philcon Financial Report 53 ConJosé Financial Report 54 Torcon 3 Financial Report 59 Noreascon 4 Financial Report 62 Interaction Financial Report 63 WSFS Business Meeting Procedures 65 Main Business Meeting Agenda, Saturday…………………………………...... 69 Report of the Mark Protection Committee 73 ConAdian Financial Report 77 Aussiecon Three Financial Report 78 Main Business Meeting Agenda, Sunday………………………….................... 79 Time Travel Worldcon Report………………………………………………… 81 Response to the Time Travel Worldcon Report, from the 1939 World Science Fiction Convention…………………………… 82 WSFS Constitution, with amendments ratified at Torcon 3……...……………. 83 Standing Rules ……………………………………………………………….. 96 Proposed Agenda for Noreascon 4, including Business Passed On from Torcon 3…….……………………………………… 100 Site Selection Report………………………………………………………… 106 Attendance List ………………………………………………………………. 109 Resolutions and Rulings of Continuing Effect………………………………… 111 Mark Protection Committee Members………………………………………… 121 Introduction All three meetings were held in the Ontario Room of the Fairmont Royal York Hotel. The head table officers were: Chair: Kevin Standlee Deputy Chair / P.O: Donald Eastlake III Secretary: Pat McMurray Timekeeper: Clint Budd Tech Support: William J Keaton, Glenn Glazer [Secretary: The debates in these minutes are not word for word accurate, but every attempt has been made to represent the sense of the arguments made. -

FANAC Fan History Project UPDATE 12

FANAC Fan History Project UPDATE 12 April 17, 2020 Greetings and felicitations. I hope this update finds you all well – we are in living in surreal and frightening times. For us, wallowing in fan history is not only a passion but a good way to focus on something other than the pandemic news. Apparently, others feel the same way. We’ve had a number of scans from new contributors, as well as our stalwarts. In particular, new material has been provided by Rich Lynch, Sheryl Birkhead, Joe Patrizio, Mike Saler, Syd Weinstein and Tom Whitmore. CoNZealand Retro Hugo Awards nominations: We’ve completed our work on the Retro Hugos for 2020. Final nominees were announced recently by CoNZealand, and we’ve assembled a page of links for the fannish material nominated in the categories of Best Related Work, Best Fanzine and Best Fan Writer. Our webmaster, Edie Stern, combed through all the 1944 fan publications available on the net to make the list as complete as possible. We want to thank CoNZealand, Steve Davidson (Amazing Stories), Mike Glyer (File 770), Dave Langford (Ansible), Andrew Porter (news lists) and Locus for promoting and linking to our effort. You can access the material at http://fanac.org/fanzines/Retro_Hugos.html . FANAC by the Numbers. We have passed what feel to us like some significant milestones in our archiving - over 10,000 fanzine issues and over 150,000 pages scanned. That’s not counting pages in some of our largest runs like Opuntia, MT Void and TNFF. It does include over 3,000 newszines. -

H K a N D C U L T F I L M N E W S

More Next Blog» Create Blog Sign In H K A N D C U L T F I L M N E W S H K A N D C U LT F I L M N E W S ' S FA N B O X W E L C O M E ! HK and Cult Film News on Facebook I just wanted to welcome all of you to Hong Kong and Cult Film News. If you have any questions or comments M O N D AY, D E C E M B E R 4 , 2 0 1 7 feel free to email us at "SURGE OF POWER: REVENGE OF THE [email protected] SEQUEL" Brings Cinema's First Out Gay Superhero Back to Theaters in January B L O G A R C H I V E ▼ 2017 (471) ▼ December (34) "MORTAL ENGINES" New Peter Jackson Sci-Fi Epic -- ... AND NOW THE SCREAMING STARTS -- Blu-ray Review by ... ASYLUM -- Blu-ray Review by Porfle She Demons Dance to "I Eat Cannibals" (Toto Coelo)... Presenting -- The JOHN WAYNE/ "GREEN BERETS" Lunch... Gravitas Ventures "THE BILL MURRAY EXPERIENCE"-- i... NUTCRACKER, THE MOTION PICTURE -- DVD Review by Po... John Wayne: The Crooning Cowpoke "EXTRAORDINARY MISSION" From the Writer of "The De... "MOLLY'S GAME" True High- Stakes Poker Thriller In ... Surge of Power: Revenge of the Sequel Hits Theaters "SHOCK WAVE" With Andy Lau Cinema's First Out Gay Superhero Faces His Greatest -- China’s #1 Box Offic... Challenge Hollywood Legends Face Off in a New Star-Packed Adventure Modern Vehicle Blooper in Nationwide Rollout Begins in January 2018 "SHANE" (1953) "ANNIHILATION" Sci-Fi "A must-see for fans of the TV Avengers, the Fantastic Four Thriller With Natalie and the Hulk" -- Buzzfeed Portma.. -

Audiences, Gender and Community in Fan Vidding Katharina M

University of Wollongong Research Online University of Wollongong Thesis Collection University of Wollongong Thesis Collections 2011 "Veni, Vidi, Vids!" audiences, gender and community in Fan Vidding Katharina M. Freund University of Wollongong, [email protected] Recommended Citation Freund, Katharina M., "Veni, Vidi, Vids!" audiences, gender and community in Fan Vidding, Doctor of Philosophy thesis, School of Social Sciences, Media and Communications, Faculty of Arts, University of Wollongong, 2011. http://ro.uow.edu.au/theses/3447 Research Online is the open access institutional repository for the University of Wollongong. For further information contact the UOW Library: [email protected] “Veni, Vidi, Vids!”: Audiences, Gender and Community in Fan Vidding A thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the award of the degree Doctor of Philosophy From University of Wollongong by Katharina Freund (BA Hons) School of Social Sciences, Media and Communications 2011 CERTIFICATION I, Katharina Freund, declare that this thesis, submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the award of Doctor of Philosophy, in the Arts Faculty, University of Wollongong, is wholly my own work unless otherwise referenced or acknowledged. The document has not been submitted for qualifications at any other academic institution. Katharina Freund 30 September, 2011 i ABSTRACT This thesis documents and analyses the contemporary community of (mostly) female fan video editors, known as vidders, through a triangulated, ethnographic study. It provides historical and contextual background for the development of the vidding community, and explores the role of agency among this specialised audience community. Utilising semiotic theory, it offers a theoretical language for understanding the structure and function of remix videos. -

The Capitol Dome

THE CAPITOL DOME The Capitol in the Movies John Quincy Adams and Speakers of the House Irish Artists in the Capitol Complex Westward the Course of Empire Takes Its Way A MAGAZINE OF HISTORY PUBLISHED BY THE UNITED STATES CAPITOL HISTORICAL SOCIETYVOLUME 55, NUMBER 22018 From the Editor’s Desk Like the lantern shining within the Tholos Dr. Paula Murphy, like Peart, studies atop the Dome whenever either or both America from the British Isles. Her research chambers of Congress are in session, this into Irish and Irish-American contributions issue of The Capitol Dome sheds light in all to the Capitol complex confirms an import- directions. Two of the four articles deal pri- ant artistic legacy while revealing some sur- marily with art, one focuses on politics, and prising contributions from important but one is a fascinating exposé of how the two unsung artists. Her research on this side of can overlap. “the Pond” was supported by a USCHS In the first article, Michael Canning Capitol Fellowship. reveals how the Capitol, far from being only Another Capitol Fellow alumnus, John a palette for other artist’s creations, has been Busch, makes an ingenious case-study of an artist (actor) in its own right. Whether as the historical impact of steam navigation. a walk-on in a cameo role (as in Quiz Show), Throughout the nineteenth century, steam- or a featured performer sharing the marquee boats shared top billing with locomotives as (as in Mr. Smith Goes to Washington), the the most celebrated and recognizable motif of Capitol, Library of Congress, and other sites technological progress. -

For Fans by Fans: Early Science Fiction Fandom and the Fanzines

FOR FANS BY FANS: EARLY SCIENCE FICTION FANDOM AND THE FANZINES by Rachel Anne Johnson B.A., The University of West Florida, 2012 B.A., Auburn University, 2009 A thesis submitted to the Department of English and World Languages College of Arts, Social Sciences, and Humanities The University of West Florida In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts 2015 © 2015 Rachel Anne Johnson The thesis of Rachel Anne Johnson is approved: ____________________________________________ _________________ David M. Baulch, Ph.D., Committee Member Date ____________________________________________ _________________ David M. Earle, Ph.D., Committee Chair Date Accepted for the Department/Division: ____________________________________________ _________________ Gregory Tomso, Ph.D., Chair Date Accepted for the University: ____________________________________________ _________________ Richard S. Podemski, Ph.D., Dean, Graduate School Date ACKNOWLEDGMENTS First, I would like to thank Dr. David Earle for all of his help and guidance during this process. Without his feedback on countless revisions, this thesis would never have been possible. I would also like to thank Dr. David Baulch for his revisions and suggestions. His support helped keep the overwhelming process in perspective. Without the support of my family, I would never have been able to return to school. I thank you all for your unwavering assistance. Thank you for putting up with the stressful weeks when working near deadlines and thank you for understanding when delays -

___... -.:: GEOCITIES.Ws

__ __ _____ _____ _____ _____ ____ _ __ / / / / /_ _/ / ___/ /_ _/ / __ ) / _ \ | | / / / /__/ / / / ( ( / / / / / / / /_) / | |/ / / ___ / / / \ \ / / / / / / / _ _/ | _/ / / / / __/ / ____) ) / / / /_/ / / / \ \ / / /_/ /_/ /____/ /_____/ /_/ (_____/ /_/ /_/ /_/ _____ _____ _____ __ __ _____ / __ ) / ___/ /_ _/ / / / / / ___/ / / / / / /__ / / / /__/ / / /__ / / / / / ___/ / / / ___ / / ___/ / /_/ / / / / / / / / / / /___ (_____/ /_/ /_/ /_/ /_/ /_____/ _____ __ __ _____ __ __ ____ _____ / ___/ / / / / /_ _/ / / / / / _ \ / ___/ / /__ / / / / / / / / / / / /_) / / /__ / ___/ / / / / / / / / / / / _ _/ / ___/ / / / /_/ / / / / /_/ / / / \ \ / /___ /_/ (_____/ /_/ (_____/ /_/ /_/ /_____/ A TIMELINE OF THE MULTIVERSE Version 1.21 By K. Bradley Washburn "The Historian" ______________ | __ | | \| /\ / | | |/_/ / | | |\ \/\ / | | |_\/ \/ | |______________| K. Bradley Washburn HISTORY OF THE FUTURE Page 2 of 2 FOREWARD Relevant Notes WARNING: THIS FILE IS HAZARDOUS TO YOUR PRINTER'S INK SUPPLY!!! [*Story(Time Before:Time Transpired:Time After)] KEY TO ABBREVIATIONS AS--The Amazing Stories AST--Animated Star Trek B5--Babylon 5 BT--The Best of Trek DS9--Deep Space Nine EL--Enterprise Logs ENT--Enterprise LD--The Lives of Dax NE--New Earth NF--New Frontier RPG--Role-Playing Games S.C.E.--Starfleet Corps of Engineers SA--Starfleet Academy SNW--Strange New Worlds sQ--seaQuest ST--Star Trek TNG--The Next Generation TNV--The New Voyages V--Voyager WLB—Gateways: What Lay Beyond Blue italics - Completely canonical. Animated and live-action movies, episodes, and their novelizations. Green italics - Officially canonical. Novels, comics, and graphic novels. Red italics – Marginally canonical. Role-playing material, source books, internet sources. For more notes, see the AFTERWORD K. Bradley Washburn HISTORY OF THE FUTURE Page 3 of 3 TIMELINE circa 13.5 billion years ago * The Big Bang. -

Coping Strategies: Three Decades of Vietnam War in Hollywood

Coping Strategies: Three Decades of Vietnam War in Hollywood EUSEBIO V. LLÁCER ESTHER ENJUTO The Vietnam War represents a crucial moment in U.S. contemporary history and has given rise to the conflict which has so intensively motivated the American film industry. Although some Vietnam movies were produced during the conflict, this article will concentrate on the ones filmed once the war was over. It has been since the end of the war that the subject has become one of Hollywood's best-sellers. Apocalypse Now, The Return, The Deer Hunter, Rambo or Platoon are some of the titles that have created so much controversy as well as related essays. This renaissance has risen along with both the electoral success of the conservative party, in the late seventies, and a change of attitude in American society toward the recently ended conflict. Is this a mere coincidence? How did society react to the war? Do Hollywood movies affect public opinion or vice versa? These are some of the questions that have inspired this article, which will concentrate on the analysis of popular films, devoting a very brief space to marginal cinema. However, a general overview of the conflict it self and its repercussions, not only in the soldiers but in the civilians back in the United States, must be given in order to comprehend the between and the beyond the lines of the films about Vietnam. Indochina was a French colony in the Far East until its independence in 1954, when the dictator Ngo Dinh Diem took over the government of the country with the support of the United States. -

The Human Adventure Is Just Beginning Visions of the Human Future in Star Trek: the Next Generation

AMERICAN UNIVERSITY HONORS CAPSTONE The Human Adventure is Just Beginning Visions of the Human Future in Star Trek: The Next Generation Christopher M. DiPrima Advisor: Patrick Thaddeus Jackson General University Honors, Spring 2010 Table of Contents Basic Information ........................................................................................................................2 Series.......................................................................................................................................2 Films .......................................................................................................................................2 Introduction ................................................................................................................................3 How to Interpret Star Trek ........................................................................................................ 10 What is Star Trek? ................................................................................................................. 10 The Electro-Treknetic Spectrum ............................................................................................ 11 Utopia Planitia ....................................................................................................................... 12 Future History ....................................................................................................................... 20 Political Theory .................................................................................................................... -

Blunderful-World-Of-Bloopers.Pdf

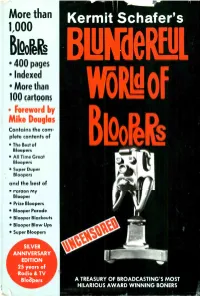

o More than Kermit Schafer's 1,000 BEQ01416. BLlfdel 400 pages Indexed More than 100 cartoons WÖLof Foreword by Mike Douglas Contains the com- plete contents of The Best of Boo Ittli Bloopers All Time Great Bloopers Super Duper Bloopers and the best of Pardon My Blooper Prize Bloopers Blooper Parade Blooper Blackouts Blooper Blow Ups Super Bloopers SILVER ANNIVERSARY EDITION 25 years of Radio & TV Bloópers A TREASURY OF BROADCASTING'S MOST HILARIOUS AWARD WINNING BONERS Kermit Schafer, the international authority on lip -slip- pers, is a veteran New York radio, TV, film and recording Producer Kermit producer. Several Schafer presents his Blooper record al- Bloopy Award, the sym- bums and books bol of human error in have been best- broadcasting. sellers. His other Blooper projects include "Blooperama," a night club and lecture show featuring audio and video tape and film; TV specials; a full - length "Pardon My Blooper" movie and "The Blooper Game" a TV quiz program. His forthcoming autobiography is entitled "I Never Make Misteaks." Another Schafer project is the establish- ment of a Blooper Hall of Fame. In between his many trips to England, where he has in- troduced his Blooper works, he lectures on college campuses. Also formed is the Blooper Snooper Club, where members who submit Bloopers be- come eligible for prizes. Fans who wish club information or would like to submit material can write to: Kermit Schafer Blooper Enterprises Inc. Box 43 -1925 South Miami, Florida 33143 (Left) Producer Kermit on My Blooper" movie opening. (Right) The million -seller gold Blooper record. -

Between Sacred and Secular: the Pop Cult Saviour Approacheth!

Between Sacred and Secular: The Pop Cult Saviour Approacheth! Christopher Hartney In The Secret Life of Puppets, Victoria Nelson has demonstrated that the popular culture of the twentieth century shows an increasing tendency to be fascinated by automatons and puppets in human form.1 She also shows how the puppet gives rise to the concept of puppet-master (human or divine) and stories of automatons with increasing frequency take on a Gnostic cosmology using this basic relationship of human-automaton/human-god to set the mood. This is the case from Blade-Runner2 to The Matrix3 and, through a slightly more oblique path, onto Philip Pullman whose His Dark Materials trilogy finds itself a place within the pattern.4 We remain fascinated with how the puppet operates in this predominantly Gnostic schema because the automaton or alien presents us with a gauge against which we parry our own measure of human experience. These ‘other’ beings, however, by allowing us to reflect on ourselves, bring us so close to our understanding of self that inclusion of a sacred aura or reference is unavoidable. One example of a hero, I feel, takes this relationship to another level not because he is a well-known pop hero, but in the way he is depicted as such. Although this character appears in a 1979 film, I will argue that his example allows us a vision of a future where pop, secular and sacred become incorporated in a new sense of self in Western culture. Stephen Hopkins’ 2004 biopic based on Roger Lewis’ biography of Peter Sellers5 (with Australian actor Geoffrey Rush cast in over 30 roles6) touches again on an unforgettable period in the cultural life of 1 Victoria Nelson: The Secret Life of Puppets, Cambridge, Massachusetts and London, 2001.