BIM PR/CE MF01/PCO2 Plus Postage

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Coloma Courier and the Benton Harbor Heraljd

THE COLOMA COURIER AND THE BENTON HARBOR HERALJD COLOMA, MICHIGAN, FRIDAY, JUNE 8, 1928 VOL. 34 NO 46 rV-, BUMBAUGH MURDER WEBER WON OVER NOTICE OF mm OF BRIDGMAN MAN KILLED NOTICE or HEETING OE CHILDREN WILL GIVE BOARD OF REVIEW OF TRIAL IS STARTED HOUSE OF DAVID TEAM IN AUTOMOBILE WRECK BOARD OE REVIEW OE SUNDAY'S PROGRAM lOMHIP OF COLOHA VILIACE OE COLOHA IN CIRCUIT COURT Crystal Palace Bali Team Scored Jake Frederick of Bridgman Held Re- Very Intere«ding Program Will be To all persons liable to assessment To all persons liable to assessemnt Another Victory Last Sunday- sponsible For Death—Is Accused of Given at Community Church at II for taxes In the Township of Coloma. for taxes in the Village of Coloma, Jury W«8 Secured Tuesday Morning Strong Benton Harbor Team Will County of Berrien, State of Michigan, driving a Car While Drunk—Fatal County of Berrien, State of Michigan, O'clock June 10th. for the year 1028. for the year 1028. Crap,a Near Bangor And flnt WllneMM Were Called— Flay at Paw Paw lake Next Sunday Notice is hereby given, that tiie as- Notice Is hereby given, that the as- The annual Children's Day program sessment roll for the said Township of will Im* given at the Community Before a crowd of 1,00# baseball fans One man was killed, two automo- sessment roll for the said Village of Htale Spnnif; liiu Surprlw by Bring- Coloma, for the year 1028 has been church in Coloma on Sunday, June 10, at the Isrealite park in Benton Harbor biles were wrecked, and five other per- Coloma, for the year 1028 has been completed and that the board of re- starting at 11:00 o'clock a. -

Aauw Fall2015 Bulletin Final For

AAUWCOLORADObulletin fall 2015 Fall Leadership Conference-- Focusing On the Strategic Plan Our Fall Leadership Conference will be held August 28-29 at Lion Square Lodge in Vail, Colorado. Lion Square Lodge is located in the Lionshead area of Vail. The group rates are available for up to 2 days prior and 2 days after our conference subject to availability. The Fall Conference is a time for state and branch offi cers to meet and work together. The conference is open to any member, but branches should be sure to have their offi cers attend and participate. This is your opportunity to help us as we work toward the achieve- ment of the state strategic plan. This year’s conference will focus on areas identifi ed in the strategic plan. We have also utilized input received from Branch Presidents on a survey conducted this spring where the greatest need identifi ed was Mission Based Pro- gramming. We will be incorporating the topic of Mission Based Programing during the conference. Branch Program and Branch Membership Chairs should also attend to gain this important information. There will be a time for Branch Presidents/Administrators who arrive on Friday afternoon to meet together. This will be an opportunity to get acquainted with your peers and share successes and provide input to the state offi cers on what support you need. The state board will also be meeting on Saturday. Lion Square Lodge Lounge Area The tentative schedule, hotel information and registration are on pages 2-3 of this Bulletin. IN THIS ISSUE: FALL LEADERSHIP CONFERENCE...1-3, PRESIDENT’S MESSAGE...4, PUBLIC POLICY...4 LEGISLATIVE WRAPUP...5-6, WOMEN’S HALL OF FAME BOOKLIST...7-8 WOMEN POWERING CHANGE...9, BRANCHES...10 MEMBERSHIP MATTERS...11, MCCLURE GRANT APPLICATION...12 AAUW Colorado 2015 Leadership Conference Lions Square Lodge, Vail, CO All meetings will be held in the Gore Creek & Columbine Rooms (Tentative Schedule) Friday, August 28 2:00 – 3:30 p.m. -

National History Day in Colorado

2020 COMMUNITY REPORT N a t i o n a l H i s t o r y D a y i n C o l o r a d o TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. OVERVIEW ......................................................................................................................................................... 1 2. GOVERNANCE & STAFF ................................................................................................................................... 3 3. REGIONAL CORNER ......................................................................................................................................... 7 4. STATE CONTEST ............................................................................................................................................... 8 5. NATIONAL CONTEST ......................................................................................................................................... 9 6. SHOWCASE BREAKFAST ............................................................................................................................... 12 7. PAPER JOURNAL ............................................................................................................................................ 13 8. FILM FESTIVAL ................................................................................................................................................ 14 9. TEACHER TRAININGS ................................................................................................................................... 15 10. ADDITIONAL PROGRAMMING -

The West – 1800-1860

The West – 1800-1860 Cynthia Williams Resor Teaching American History December 7, 2012 Middle School – 2nd session; 4th year Activity • How did travelers in the early 1800s find their destination in areas with no roads? • What “sign-posts” did they use? • What “roads” did they use? • Draw/label the major rivers of Kentucky on the map. – Would adding the major modern highways be easier? • Draw/label the major rivers of the USA on the map. – Would adding the major modern highways be easier? The West before the Civil War was not a blank space . Today’s theme: Pretend you are a person living on the WEST side of the Mississippi River in 1804. You might be a ►French Canadian ► British ► Native American ► Russian ► Spanish ► A person with a mixed heritage How would you view Americans as they move into your home? Typical outline of textbooks What is missing? • Chapter 20 - Jeffersonian America: A Second Revolution? The Election of 1800 – Jeffersonian Ideology – Westward Expansion: The Louisiana Purchase – A New National Capital: Washington, D.C. – A Federalist Stronghold: John Marshall's Supreme Court – Gabriel's Rebellion: Another View of Virginia in 1800 • Chapter 21 - The Expanding Republic and the War of 1812 The Importance of the West – Exploration: Lewis and Clark – Diplomatic Challenges in an Age of European War – Native American Resistance in the Trans-Appalachian West – The Second War for American Independence – Claiming Victory from Defeat • Chapter 24 - The Age of Jackson The Rise of the Common Man – A Strong Presidency – The South Carolina Nullification Controversy – The War Against the Bank – Jackson vs. -

BORDERLANDS History Project Explores Complexity and Community in Southern Colorado

WINTER 2019 STATETHE MAGAZINE OF THE COLORADO STATE UNIVERSITY SYSTEM BORDERLANDS History project explores complexity and community in southern Colorado FARM TO FOOD BANK HIGH HOPES FOR AURORA GROWING COLORADO STATE’S LAND-GRANT LEGACY The Arkansas River, with headwaters near Leadville, Colorado, flows east across the Plains to the Mississippi River. A section of river in what is now southeastern Colorado once formed the border be- tween Mexico and the United States. Photo: Courtesy of History Colorado BORDERLANDS of SOUTHERN COLORADO he most prominent landmark near Pueblo, Colorado, the moun- T tain that inspired the patriotic song “America the Beautiful,” is Pikes Peak. Rising to 14,115 feet, it is named for Zebulon Mont- gomery Pike, a U.S. Army explorer who traveled through the Southwest in 1806 and 1807 on a mission of geopolitical reconnaissance, soon adding to the young nation’s lust for westward expansion. His accounts were compiled and translated into three languages for readers abroad. “Pikes Peak or Bust!” was the motto for prospectors during the Colorado gold rush. BY COLEMAN CORNELIUS 22 THE MAGAZINE OF THE COLORADO STATE UNIVERSITY SYSTEM STATE | WINTER 2019 23 "We’re using borderlands as a lens to reveal the ways in which people from multiple places, perspectives, and traditions come together in these spaces. Sometimes they collide and some- times they mix, but they always form new ways of being. We feel like that really represents southern Colorado,” The exhibit is part of a History Colorado initiative called Borderlands of Southern Colorado. Through interconnected displays and lectures at its museums in Pueblo, Trinidad, and Fort Garland, History Colorado presents southern Colorado as a region whose inhabitants have been affected across generations by historically shifting political boundaries and related strife. -

Apanese Am in WOI

'Little B Japanese Am in WOI On February 16, 1960 a special agent of the Fe Beach, California, home.. a $1,000 fine assessed aga "Toots," along with her sis sisters), were found guilty escaping from the Trinidal Billie and Flo received t $1,000 fines while Tsuruk year sentence and the $1,( in the Federal ReformatoI The agent described Tsuru • feelings that the governme to be such a great length ( The Shitara sisters' arres conspiracy to commit trea Colorado during World \\ Japanese-American sisters on trial for treason" news file photo nation during the war. 7 1 Accompanying text reads: among individuals, groups "ACME TELEPHOTO NEW YORK BUREAU ACME TELEPHOTO in an atmosphere of cultur JAPANESE-AMERICAN SISTERS ON TRIAL FOR TREASON Southeastern Colorado his DENVER, Col. -- The death penalty may be imposed upon these three California-born Japanese sisters if they are convicted of treason in thier current trial here. The three, Mrs. The government, media, a Billie Shitara Tanigoshi (walking), Mrs. Florence Shivze Otani (upper left), and Mrs Tsuro other nonwhite people of "Toots" Wallace (below) are charged with having aided two German prisoners of war, Corporals Heinrich Haider and Herman August Loescher to escape from a Trinidad, Col., internment camp last October. The Germans are witnesses in the current trial. Robert Koehler has an MA in Cull SEE PRESS WIRES in Mexican American Studies frol Divinity School and is currently cc Credit "Acme Telephoto" blr 8/8/44 NY Bureau": United Press International ethnic history, Japanese American i 12 t \ , , 'Little Benedict Arnolds in Skirts': Japanese American Women and Treason in World War II Colorado! By Robert Koehler On February 16, 1960, fifty-year-old Tsuruko Endo Wallace met a special agent of the Federal Bureau of Investigation at her Long Beach, California, home. -

High Plains Guide Festivals, Fairs, and Rodeos 2018

HIGH PLAINS GUIDE FESTIVALS, FAIRS, AND RODEOS 2018 TABLE OF CONTENTS 10 16 24 Hobson’s Colorado The Life of a Choice: A Letter Abandoned County Sheriff from Fort Lyon 30 32 34 50 Years of The “Old Wells” Community of Cheyenne After That Theater County 36 38 44 414,000 Acres Lillian Cline A Journey of of Hidden Sapp Stones Treasure Kiowa County Independent Publisher: Betsy Barnett 1316 Maine Street Editor: Priscilla Waggoner 47 P.O. Box 272 Layout and Design: William Eads, Colorado 81036 Brandt A Hundred (Plus) Years of Hanagans Kiowa County Independent © July 2018 kiowacountyindependent.com July 2018 | HIGH PLAINS GUIDE | i ii | HIGH PLAINS GUIDE | July 2018 kiowacountyindependent.com FESTIVALS, FAIRS, AND RODEOS kiowacountyindependent.com July 2018 | HIGH PLAINS GUIDE | 1 EVENTS KIOWA COUNTY FAIR & KIT CARSON DAY LINCOLN COUNTY FAIR & RODEO Kit Carson, Colorado RODEO Eads, Colorado September 1, 2018 Hugo, Colorado September 5-9, 2018 August 6-11, 2018 https://www.facebook. BACA COUNTY FAIR & http://seelincolncounty.com/ com/Kiowa-County- RODEO event/2018-lincoln-county-fair- Fair-2018-272585516634180/ Springfield, Colorado rodeo/ July 23-August 5, 2018 SAND & SAGE ROUNDUP https://www.facebook.com/ KIT CARSON COUNTY FAIR & Lamar, Colorado BacaFairAndRodeoInc/?ref=br_ PRO RODEO August 4-11, 2018 rs Burlington, Colorado https://www.sandandsageroundup. July 23-28, 2018 com/ ARK VALLEY FAIR & RODEO https://www.facebook.com/ Rocky Ford, Colorado Kit-Carson-County-Fair-Pro- Rodeo-164647266888216/ BENT COUNTY FAIR & August 15-19, 2018 RODEO -

Girl Scout Scavenger Hunt Answer Sheet

Girl Scout Scavenger Hunt Answer Sheet (We have attempted to find all answers that are correct in this answer sheet. There is a possibility that we may have missed one or more. If you find an answer that is not included on this sheet, please take these steps: • Check your answer to make sure you have bio information to back it up • Send an email to [email protected] and share your information with Colorado Women’s Hall of Fame • You will receive a response about your answer • If appropriate, we will add your answer to the Answer Sheet and reissue it to the Girl Scout office so future troops doing the exercise will have your answer included. Thank you for delving into the remarkable achievements of our Inductees.) One of the options for earning a Colorado Women’s Hall (CWHF) of Fame fun patch is to complete the Scavenger Hunt below. There are clues at the end of the list that may help you find some answers. Please answer at least 15 of the 25 questions below using the following website as your source: www.cogreatwomen.org 1. How often does the Colorado Women’s Hall of Fame induct new women into the Hall? How many women are inducted at each Induction? ANSWER: • Every 2 years on an even year cycle, e.g.2020 • Ten women are inducted (4 historical and 6 contemporary). 2. What are the three criteria for a woman being selected as an Inductee into the Colorado Women’s Hall of Fame? Who can nominate? When? ANSWER: Criteria: • Made significant and enduring contributions to her fil(40%). -

Life in an Adobe Castle, 1833-1849

. " Life in an Adobe Castle, 1833-1849 BY ENID THOMPSON Bent's Old Fort was an outpost of American civilization situated on the southwestern edge of the American frontier. A symbol of Manifest Destiny, the fort was located on the Moun tain Branch of the Santa Fe Trail, the crossroads of trade among the Indians of the plains, the trappers of the mountains, and the traders of the Southwest. Bent's Old Fort was the largest of all the trading posts in the mountain-plains region. The people who built and maintained the fort, and many of those who visited it, ;<an s a"I" Pueblo z(/) Spanish P e aks ~'':. ~.:~ z~ 5 ----~--..:~::_ Hoping to cash in on this trade, in December 1830 while were, in large part, the people who. guided by economic neces William Bent was trapping in the New Mexican mountains sity and commercial acumen, carried forward the Americaniza Ceran St. Vrain and Charles Bent formed a partnership so that tion of the area during the 1830s and 1840s. one of them could tend to the trade in Taos while the other could In the 1830s the trade on the Santa Fe Trail was increasing freight their trade goods on the Santa Fe Trail. By 1832 news of as the fur trade market was decreasing. With the beaver virtu the partnership of the Bents and St. Vrain had spread eastward. ally trapped out of the Missouri River drainage area and the On 10 January 1834 William Laidlaw, an American Fur Com introduction of the silk hat into European and American fash pan~ trader at Fort Pierre in present-day South Dakota, wrote ion, the fur trade market was severely affected. -

Wagon Tracks

WAGON TRACKS s;=~r~ ~ ;=~ ~ ~ ~;~:I~ ;=~ss[=][== = VOLUME 2 NOVEMBER 1987 NUMBER 1 HUTCHINSON SYMPOSIUM "Do you know the way to MEMBERSHIP AT 500 & Over 350 participants enjoyed Santa Fe? I'm going there RENEW ALS DUE SOON the second Santa Fe Trail Sympo in '89." The goal of having 500 SFTA sium at Hutchinson, September Composed,& sung by Paul Bentrup members by the end of 1987 was 24-27. Activities and presenta 1987 Symposium, Hutchinson achieved on November 2. The lat tions received attention in state est additions are listed within. A and regional news media. Evalua NEXT SYIY1POSIUM roster of all members will be dis tion forms completed by those at IN SANTA FE tributed early next year. Several tending indicate that all programs have paid 1988 dues and everyone were highly successful. Further A total of five locations made else is invited to renew member information about the conference bids to the SFTA Board to host fu ship by January 1. Two member is in the President's Column, page ture Symposiums: Overland Park, ship forms are enclosed with this 2, and photos taken by Joan Myers Santa Fe, Arrow Rock, La Junta/ mailing. Please use one to renew appear inside. Bent's Fort, and Las Vegas/Fort your membership for 1988 and use A few comments from evaluation Union. Symposiums are held in the other to recruit a new member. forms follow: "I was inspired to odd-numbered years. Since the If every membe'r signs up one new learn more about the SFT and all Santa Fe Trail Center at Larned member, the 1988 goal of at least early trails." "I'm a newSFTbuff sponsors a Trail Rendezvous in 1,000 members will be met. -

The Hastings Mine Disaster of 1917 for Instance, As Our Senior Curator of Artifacts Eric L

The Magazine of History Colorado Spring 2017 Sponsored by At the History Colorado Center Hattie McDaniel: World Icon, The One-Chance Men: The Hastings Mine Backstory Features Denver Colorado Unknown Disaster of 1917 & Rio Grande Chinaware Colorado Heritage The Magazine of History Colorado History Colorado Center Steve Grinstead Managing Editor 1200 Broadway Darren Eurich, State of Colorado/IDS Graphic Designer Denver, Colorado 80203 303/HISTORY Melissa VanOtterloo and Aaron Marcus Photographic Services Administration Public Relations Colorado Heritage (ISSN 0272-9377), published by History 303/866-3355 303/866-3670 Colorado, contains articles of broad general and educational Membership Group Sales Reservations interest that link the present to the past. Heritage is distributed 303/866-3639 303/866-2394 quarterly to History Colorado members, to libraries, and to institutions of higher learning. Manuscripts must be documented Museum Rentals Archaeology & when submitted, and originals are retained in the Publications 303/866-4597 Historic Preservation office. An Author’s Guide is available; contact the Publications 303/866-3392 Research Librarians office. History Colorado disclaims responsibility for statements 303/866-2305 State Historical Fund of fact or of opinion made by contributors. History Colorado Education 303/866-2825 also publishes Explore, a bimonthy publication of programs, 303/866-4686 Support Us events, and exhibition listings. 303/866-4737 Postage paid at Denver, Colorado For details about membership visit HistoryColorado.org and click All History Colorado members receive Colorado Heritage as a on “Membership,” email us at [email protected], or write to benefit of membership. Individual subscriptions are available Membership Office, History Colorado Center. -

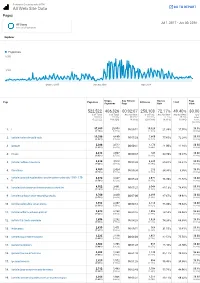

All Web Site Data GO to REPORT Pages

Colorado Encyclopedia GTM All Web Site Data GO TO REPORT Pages Jul 1, 2017 - Jun 30, 2018 All Users 100.00% Pageviews Explorer Pageviews 6,000 3,000 October 2017 January 2018 April 2018 Unique Avg. Time on Bounce Page Page Pageviews Entrances % Exit Pageviews Page Rate Value 522,522 406,326 00:02:07 258,108 72.17% 49.40% $0.00 % of Total: % of Total: Avg for View: % of Total: Avg for View: Avg for View: % of 100.00% 100.00% 00:02:07 100.00% 72.17% 49.40% Total: (522,522) (406,326) (0.00%) (258,108) (0.00%) (0.00%) 0.00% ($0.00) 1. / 37,369 20,958 00:00:51 19,026 21.89% 17.05% $0.00 (7.15%) (5.16%) (7.37%) (0.00%) 2. /article/colorado-gold-rush 10,788 8,689 00:05:33 7,869 77.65% 72.28% $0.00 (2.06%) (2.14%) (3.05%) (0.00%) 3. /people 5,286 3,522 00:00:41 1,274 21.00% 12.16% $0.00 (1.01%) (0.87%) (0.49%) (0.00%) 4. /maps 4,812 2,947 00:00:37 148 32.89% 10.27% $0.00 (0.92%) (0.73%) (0.06%) (0.00%) 5. /article/ludlow-massacre 4,618 4,072 00:04:26 3,835 85.21% 82.27% $0.00 (0.88%) (1.00%) (1.49%) (0.00%) 6. /timelines 4,080 2,424 00:00:36 253 34.80% 8.80% $0.00 (0.78%) (0.60%) (0.10%) (0.00%) /article/spanish-exploration-southeastern-colorado-1590–179 7.