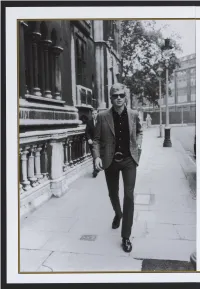

Brian Epstein by Anthony Decurtis the Beatles’Visionary Manager Took the Fab Four to “The Toppermost of the Poppermost.”

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Canadian Beatles Albums Identification Guide Updated: 22 De 16

Canadian Beatles Albums Identification Guide Updated: 22 De 16 Type 1 Rainbow Label Capitol Capitol Records of Canada contracted Beatlemania long before their larger and better-known counterpart to the south. Canadian Capitol's superior decision-making brought Beatles records to Canada in early 1963. After experimenting with the release of a few singles, Capitol was eager to release the Beatles' second British album in Canada. Sources differ as to the release date of the LP, but surely by December 2, 1963, Canada's version of With the Beatles became the first North American Beatles album. Capitol-USA and Capitol-Canada were negotiating the consolidation of their releases, but the US release of The Beatles' Second Album had a title and contained songs that were inappropriate for Canadian release. After a third unique Canadian album, album and single releases were unified. From Something New on, releases in the two countries were nearly identical, although Capitol-Canada continued to issue albums in mono only. At the time when Beatlemania With the Beatles came out, most Canadian pop albums were released in the "6000 Series." The label style in 1963 was a rainbow label, similar to the label used in the United States but with print around the rim of the label that read, "Mfd. in Canada by Capitol Records of Canada, Ltd. Registered User. Copyrighted." Those albums which were originally issued on this label style are: Title Catalog Number Beatlemania With the Beatles T-6051 (mono) Twist and Shout T-6054 (mono) Long Tall Sally T-6063 (mono) Something New T-2108 (mono) Beatles' Story TBO-2222 (mono) Beatles '65 T-2228 (mono) Beatles '65 ST-2228 (stereo) Beatles VI (mono) T-2358 Beatles VI (stereo) ST-2358 NOTE: In 1965, shortly before the release of Beatles VI, Capitol-Canada began to release albums in both mono and stereo. -

HITMAKERS – 6 X 60M Drama

HITMAKERS – 6 x 60m drama LOGLINE In Sixties London, the managers of the Beatles, the Stones and the Who struggle to marry art and commerce in a bid to become the world’s biggest hitmakers. CHARACTERS Andrew Oldham (19), Beatles publicist and then manager of the Rolling Stones. A flash, mouthy trouble-maker desperate to emulate Brian Epstein’s success. His bid to create the anti-Beatles turns him from Epstein wannabe to out-of-control anarchist, corrupted by the Stones lifestyle and alienated from his girlfriend Sheila. For him, everything is a hustle – work, relationships, his own psyche – but always underpinned by a desire to surprise and entertain. Suffers from (initially undiagnosed) bi-polar disorder, which is exacerbated by increasing drug use, with every high followed by a self-destructive low. Nobody in the Sixties burns brighter: his is the legend that’s never been told on screen, the story at the heart of Hitmakers. Brian Epstein (28), the manager of the Beatles. A man striving to create with the Beatles the success he never achieved in entertainment himself (as either actor or fashion designer). Driven by a naive, egotistical sense of destiny, in the process he basically invents what we think of as the modern pop manager. He’s an emperor by the age of 30 – but this empire is constantly at risk of being undone by his desperate (and – to him – shameful) homosexual desires for inappropriate men, and the machinations of enemies jealous of his unprecedented, upstart success. At first he sees Andrew as a protege and confidant, but progressively as a threat. -

Für Sonntag, 21

Tägliche BeatlesInfoMail 31.03.20: BEATLES-Hoodie mit WHITE ALBUM PHOTO-Motiv /// MANY YEARS AGO ---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- Im Beatles Museum erhältlich: BEATLES-Hoodie mit WHITE ALBUM-Motiv Versenden wir gut verpackt und zuverlässig mit DHL (Info über Sendeverlauf kommt per E-Mail). THE BEATLES: Hoodie PHOTOS WHITE ALBUM SILHOUETTES ON BLACK. 59,95 € Material: 60% Baumwolle, 40 % Polyester Größen: S, M, L, XL, XXL. Weitere Hoodies: https://www.beatlesmuseum.net/?s=Hoodie&post_type=product ---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- Bestellungen auch telefonisch möglich: Di. - So. von 10.00 bis 18.00 Uhr: 0345-2903900 Innerhalb Deutschland: Bei Bestellwert unter 50 Euro: Versandanteil für Briefe; für Inland-Pakete maximal 5,00 Euro. / Ab Bestellwert 50 Euro: innerhalb Deutschland portofrei. Ins Ausland: Bei Bestellwert unter 50 Euro: Versandanteil für Briefe und Pakete: bitte erfragen. / Ab Bestellwert 50 Euro: Versandanteil minus 5 Euro. ---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- Viele Grüße sendet Dir das Team vom Beatles Museum Stefan, Martin, Daniel, Katharina und Marta ---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- 31. März - IT WAS MANY YEARS AGO TODAY … und im BEATLES-Magazin THINGS regelmäßig 50/40/30/20/10 YEARS AGO und die NEWS Ergänzungen und Korrekturen sind willkommen! #BeatlesMuseum /// www.Facebook.com/BeatlesMuseumInHalle -

MTO 11.4: Spicer, Review of the Beatles As Musicians

Volume 11, Number 4, October 2005 Copyright © 2005 Society for Music Theory Mark Spicer Received October 2005 [1] As I thought about how best to begin this review, an article by David Fricke in the latest issue of Rolling Stone caught my attention.(1) Entitled “Beatles Maniacs,” the article tells the tale of the Fab Faux, a New York-based Beatles tribute group— founded in 1998 by Will Lee (longtime bassist for Paul Schaffer’s CBS Orchestra on the Late Show With David Letterman)—that has quickly risen to become “the most-accomplished band in the Beatles-cover business.” By painstakingly learning their respective parts note-by-note from the original studio recordings, the Fab Faux to date have mastered and performed live “160 of the 211 songs in the official canon.”(2) Lee likens his group’s approach to performing the Beatles to “the way classical musicians start a chamber orchestra to play Mozart . as perfectly as we can.” As the Faux’s drummer Rich Pagano puts it, “[t]his is the greatest music ever written, and we’re such freaks for it.” [2] It’s been over thirty-five years since the real Fab Four called it quits, and the group is now down to two surviving members, yet somehow the Beatles remain as popular as ever. Hardly a month goes by, it seems, without something new and Beatle-related appearing in the mass media to remind us of just how important this group has been, and continues to be, in shaping our postmodern world. For example, as I write this, the current issue of TV Guide (August 14–20, 2005) is a “special tribute” issue commemorating the fortieth anniversary of the Beatles’ sold-out performance at New York’s Shea Stadium on August 15, 1965—a concert which, as the magazine notes, marked the “dawning of a new era for rock music” where “[v]ast outdoor shows would become the superstar standard.”(3) The cover of my copy—one of four covers for this week’s issue, each featuring a different Beatle—boasts a photograph of Paul McCartney onstage at the Shea concert, his famous Höfner “violin” bass gripped in one hand as he waves to the crowd with the other. -

FLAME TREE MUSIC PORTAL Extends the Reach of the Flame Tree Music Books

FLAME TREE PUBLISHING NEW TITLES & BACKLIST 2020 FLAME TREE MUSIC • Page 36 FLAME TREE PUBLISHING NEW TITLES & BACKLIST 2020 FLAME TREE MUSIC • Page 37 Pack of 3 books, shrink-wrapped, with a bellyband • Each 64pp book is paperback, with a stitched spine FLAME TREE • Chord and How to Play books are full colour inside MUSIC • Journals contain blank, ruled pages with chord boxes and manuscript paper Easy to Use • Internet links to flametreemusic.com Great for travel, quick access Easy to use, slim and adaptable, the Pick Up & Play offer free audio access to hear the at home, planning for and playing 3-Pack Kits will fit in a bag, or within easy Piano Sheet Music chords and scales. with others reach, as a constant companion. Rock Icons Jake Jackson Jake Jackson Definitive Encyclopedias 3-BOOK WORKING KIT FOR GUITAR 3-BOOK WORKING KIT FOR PIANO & KEYBOARD An essential aid to learning and making notes when playing the guitar, An essential aid to learning and making notes when playing the keyboard, writing songs and working with others. The Guitar Chords book gives 4 writing songs and working with others. The Piano & Keyboard Chords chords per key, plus an extra chord section for variations. book gives left- and right-hand chords, plus an extra section for variations. The Play Guitar book covers all essentials to help you start up quickly, The Play Piano & Keyboard book covers all essentials to help you start or refresh your memory, with scales for solos and basic techniques up quickly, or refresh your memory, with scales and modes explained. -

The Beatles on Film

Roland Reiter The Beatles on Film 2008-02-12 07-53-56 --- Projekt: transcript.titeleien / Dokument: FAX ID 02e7170758668448|(S. 1 ) T00_01 schmutztitel - 885.p 170758668456 Roland Reiter (Dr. phil.) works at the Center for the Study of the Americas at the University of Graz, Austria. His research interests include various social and aesthetic aspects of popular culture. 2008-02-12 07-53-56 --- Projekt: transcript.titeleien / Dokument: FAX ID 02e7170758668448|(S. 2 ) T00_02 seite 2 - 885.p 170758668496 Roland Reiter The Beatles on Film. Analysis of Movies, Documentaries, Spoofs and Cartoons 2008-02-12 07-53-56 --- Projekt: transcript.titeleien / Dokument: FAX ID 02e7170758668448|(S. 3 ) T00_03 titel - 885.p 170758668560 Gedruckt mit Unterstützung der Universität Graz, des Landes Steiermark und des Zentrums für Amerikastudien. Bibliographic information published by Die Deutsche Bibliothek Die Deutsche Bibliothek lists this publication in the Deutsche Nationalbibliografie; detailed bibliographic data are available on the Internet at http://dnb.ddb.de © 2008 transcript Verlag, Bielefeld This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 3.0 License. Layout by: Kordula Röckenhaus, Bielefeld Edited by: Roland Reiter Typeset by: Roland Reiter Printed by: Majuskel Medienproduktion GmbH, Wetzlar ISBN 978-3-89942-885-8 2008-12-11 13-18-49 --- Projekt: transcript.titeleien / Dokument: FAX ID 02a2196899938240|(S. 4 ) T00_04 impressum - 885.p 196899938248 CONTENTS Introduction 7 Beatles History – Part One: 1956-1964 -

The Beatles BC

Last Updated: 29 Jn 20 If you have a copy of Introducing the Beatles that you are trying to identify ... search on this page for 1062. Beatles records in the United States are typically found on the Capitol or Apple label. But people often ask about records, such as Introducing the Beatles, which were released by companies other than Capitol/Apple. In these articles, I will attempt to discuss the history of Beatles recordings in the US which predate their Capitol contract. Known variations of those records will be listed, along with their approximate values. The first Beatles record released anywhere was "My Bonnie" and "The Saints," with the Beatles backing Tony Sheridan. This German record (Polydor NH 24-673) was issued in two forms (with a German intro or an English intro) and with a picture sleeve. [More information can be found in this article about the Beatles' association with Tony Sheridan.] "My Bonnie" was Tony's first record and his break into the record industry. As many people know, the word "Beatles" was considered difficult to interpret by Germans, so Polydor billed the artist as Tony Sheridan and the Beat Brothers (October 1961). From that point on, Tony's band was known as the Beat Brothers, which caused some confusion to later Beatles fans. In January of 1962, Beatles manager Brian Epstein began negotiating with Polydor to release "My Bonnie" in England. Because of his negotiations, the UK "My Bonnie" release (Polydor NH 66-833) showed the artist as "Tony Sheridan and the Beatles." The record sold modestly, apparently well enough to consider releasing it in America. -

The Beatles on Film. Analysis of Movies, Documentaries, Spoofs and Cartoons 2008

Repositorium für die Medienwissenschaft Roland Reiter The Beatles on Film. Analysis of Movies, Documentaries, Spoofs and Cartoons 2008 https://doi.org/10.25969/mediarep/1299 Veröffentlichungsversion / published version Buch / book Empfohlene Zitierung / Suggested Citation: Reiter, Roland: The Beatles on Film. Analysis of Movies, Documentaries, Spoofs and Cartoons. Bielefeld: transcript 2008. DOI: https://doi.org/10.25969/mediarep/1299. Erstmalig hier erschienen / Initial publication here: https://doi.org/10.14361/9783839408858 Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Dieser Text wird unter einer Creative Commons - This document is made available under a creative commons - Namensnennung - Nicht kommerziell - Keine Bearbeitungen 3.0 Attribution - Non Commercial - No Derivatives 3.0 License. For Lizenz zur Verfügung gestellt. Nähere Auskünfte zu dieser Lizenz more information see: finden Sie hier: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0 https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0 Roland Reiter The Beatles on Film 2008-02-12 07-53-56 --- Projekt: transcript.titeleien / Dokument: FAX ID 02e7170758668448|(S. 1 ) T00_01 schmutztitel - 885.p 170758668456 Roland Reiter (Dr. phil.) works at the Center for the Study of the Americas at the University of Graz, Austria. His research interests include various social and aesthetic aspects of popular culture. 2008-02-12 07-53-56 --- Projekt: transcript.titeleien / Dokument: FAX ID 02e7170758668448|(S. 2 ) T00_02 seite 2 - 885.p 170758668496 Roland Reiter The Beatles on Film. Analysis of Movies, Documentaries, Spoofs and Cartoons 2008-02-12 07-53-56 --- Projekt: transcript.titeleien / Dokument: FAX ID 02e7170758668448|(S. 3 ) T00_03 titel - 885.p 170758668560 Gedruckt mit Unterstützung der Universität Graz, des Landes Steiermark und des Zentrums für Amerikastudien. -

A History of International Beatleweek (PDF)

The History of International Beatleweek International Beatleweek celebrates the most famous band in the world in the city where it was born – attracting thousands of Fab Four fans and dozens of bands to Liverpool each year. The history of Beatleweek goes back to 1977 when Liverpool’s first Beatles Convention was held at Mr Pickwick’s club in Fraser Street, off London Road. The two-day event, staged in October, was organised by legendary Cavern Club DJ Bob Wooler and Allan Williams, entrepreneur and The Beatles’ early manager, and it included live music, guest speakers and special screenings. In 1981, Liz and Jim Hughes – the pioneering couple behind Liverpool’s pioneering Beatles attraction, Cavern Mecca – took up the baton and arranged the First Annual Mersey Beatle Extravaganza at the Adelphi Hotel. It was a one-day event on Saturday, August 29 and the special guests were Beatles authors Philip Norman, Brian Southall and Tony Tyler. In 1984 the Mersey Beatle event moved to St George’s Hall where guests included former Cavern Club owner Ray McFall, Beatles’ press officer Tony Barrow, John Lennon’s uncle Charles Lennon and ‘Father’ Tom McKenzie. Cavern Mecca closed in 1984, and after the city council stepped in for a year to keep the event running, in 1986 Cavern City Tours was asked to take over the Mersey Beatle Convention. It has organised the annual event ever since. International bands started to make an appearance in the late 1980s, with two of the earliest groups to make the journey to Liverpool being Girl from the USA and the USSR’s Beatle Club. -

Andrew Loog Oldham by Rob Bowman As the Rolling Stones’ Manager and Producer, He Played a Seminal Role in the Creation of Modern Rock & Roll

Andrew Loog Oldham By Rob Bowman As the Rolling Stones’ manager and producer, he played a seminal role in the creation of modern rock & roll. IN 1965, TOM WOLFE FAMOUSLY DUBBED PHIL SPECTOR America’s first tycoon of teen. Great Britain in the 1960s had its own version with Andrew Loog Oldham. Similarly eccentric, Oldham sported a one-of-a-kind mix of flamboyance, fashion, attitude, chutz pah, vision, and business smarts. As comanager of the Rolling Stones from May 1963 to September 1967, and founder and co-owner of Im mediate Records from 1965 to 1970, he helped shape the future of rock, and certainly turned the music industry in the United Kingdom on its head. Along the way, between the ages of 19 and 23, he pro duced some of the greatest records in rock & roll history, leading Bill board to describe him as one of the top five producers in the world, and Cashbox to declare him a musical giant. ^ He was born in Lon don on January 29, 1944, during the Germans’ nightly bombard ment of England. His father, whom he never met, was Texas airman Andrew Loog, killed in June 1943 when his B-17 bomber was shot down over France. Raised by his mother, Celia Oldham, the preco cious teenager began working for Mary Quant during the day, at Ronnie Scott’s jazz club in the evening, and at the fabled Flamingo club after midnight. He also found time to form a (short-lived) pub lic relations firm with Pete Meaden, the future manager of the Who. -

John Lennon, “Revolution,” and the Politics of Musical Reception John Platoff Trinity College, [email protected]

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Trinity College Trinity College Trinity College Digital Repository Faculty Scholarship Spring 2005 John Lennon, “Revolution,” and the Politics of Musical Reception John Platoff Trinity College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalrepository.trincoll.edu/facpub Part of the Music Commons JOM.Platoff_pp241-267 6/2/05 9:20 AM Page 241 John Lennon, “Revolution,” and the Politics of Musical Reception JOHN PLATOFF A lmost everything about the 1968 Beatles song “Revolution” is complicated. The most controversial and overtly political song the Beatles had produced so far, it was created by John Lennon at a time of profound turmoil in his personal life, and in a year that was the turning point in the social and political upheavals of the 1960s. Lennon’s own ambivalence about his message, and conflicts about the song within the group, resulted in the release of two quite 241 different versions of the song. And public response to “Revolution” was highly politicized, which is not surprising considering its message and the timing of its release. In fact, an argument can be made that the re- ception of this song permanently changed the relationship between the band and much of its public. As we will see, the reception of “Revolution” reflected a tendency to focus on the words alone, without sufficient attention to their musical setting. Moreover, response to “Revolution” had much to do not just with the song itself but with public perceptions of the Beatles. -

Beatles History – Part One: 1956–1964

BEATLES HISTORY – PART ONE: 1956–1964 January 1956–June 1957: The ‘Skiffle Craze’ In January 1956, Lonnie Donegan’s recording of “Rock Island Line” stormed into the British hit parade and started what would become known as the ‘skiffle craze’ in Great Britain (vgl. McDevitt 1997: 3). Skiffle was originally an amateur jazz style comprising elements of blues, gospel, and work songs. The instrumentation resembled New Or- leans street bands called ‘spasms,’ which relied on home-made instru- ments. Before skiffle was first professionally recorded by American jazz musicians in the 1920s and 1930s, it had been performed at ‘rent parties’ in North American cities like Chicago and Kansas City. Many African- American migrant workers organized rent parties in order to raise money for their monthly payments (vgl. Garry 1997: 87). Skiffle provided the musical entertainment at these parties, as everybody was able to partici- pate in the band, which usually consisted of home-made acoustic guitars or a piano backed by a rhythm section of household instruments, such as a washboard, a washtub bass, and a jug (vgl. McDevitt 1997:16). Jazz trumpeter and guitarist Ken Colyer pioneered the skiffle scene in Great Britain. In 1949, he formed the Crane River Jazz Band in Cran- ford, Middlesex, together with Ben Marshall (guitar), Pat Hawes (wash- board), and Julian Davies (bass). Their repertoire included skiffle songs “to illustrate aspects of the roots of jazz and to add variety to a pro- gramme” (Dewe 1998: 4). After leaving the group in 1951, Colyer mi- grated to the United States to work with jazz musicians in New Orleans.