Page 1 22 Volume 52, Number 1 Expedition Chatrikhera

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cbse/English/2016

CBSE/ENGLISH/2016 S.NO QUESTIONS ANSWERS Q.1 Q.1 Read the passage given below : Ans.1(a) (iv) both (B) and (C) 1. Maharana Pratap ruled over Mewar only for 25 years. However. he (b) (iii) its small area and small population accomplished so much grandeur during his reign that his glory surpassed the (c) (i) the flag of Mewar seemed to be lowered boundaries of countries and time turning him into an immortal personality. (d) (iii) most of its rulers were competent He along with his kingdom became a synonym for valour, sacrifice and (e) Bappa Rawal patriotism. Mewar had been a leading Rajput kingdom even before Maharana (f) Rana Kumbha had given a new stature to the kingdom through victories and Pratap occupied the throne. Kings of Mewar, with the cooperation of their developmental work. During his reign literature and art also progressed nobles and subjects. had established such traditions in the kingdom. as extraordinarily. Rana himself was inclined towards writing and his works are read augmented their magnificence despite the hurdles of having a smaller area with reverence even today. The ambience of his kingdom was conducive to the under their command and less, population. There did come a few thorny creation of high quality work of art and literature. occasions when the flag of the kingdom seemed sliding down. Their flag (g) They compensate for lack of admirable physique by their firmbut pleasant nature. once again heaved high in the sky thanks to the gallantry and brilliance of the The ambience of Mewar remains lovely; thanks to the cheerful and liberal character people of Mewar. -

ELECTION LIST 2016 10 08 2016.Xlsx

UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF SCIENCE MOHANLAL SUKHAIDA UNIVERSITY, UDAIPUR FINAL ELECTORAL LIST 2016-17 B. SC. FIRST YEAR Declared on : 10-08-2016 S. No. NAME OF STUDENT FATHER'S NAME ADDRESS 1 AAKASH SHARMA VINOD KUMAR SHARMA E 206 DWARIKA PURI 2 ABHA DHING ABHAY DHING 201-202, SUGANDHA APARTMENT, NEW MALI COLONY, TEKRI, UDAIPUR 3 ABHISHEK DAMAMI GHANSHYAM DAMAMI DAMAMIKHERA,DHARIYAWAD 4 ABHISHEK MISHRA MANOJ MISHRA BAPU BAZAR, RISHABHDEO 5 ABHISHEK SAYAWAT NARENDRA SINGH SAYAWAT VILL-MAKANPURA PO-CHOTI PADAL TEH GHATOL 6 ABHISHEKH SHARMA SHIVNARAYAN SHARMA VPO-KARUNDA, TEH-CHHOTI SADRI 7 ADITI MEHAR KAILASH CHANDRA MEHAR RAJPUT MOHALLA BIJOLIYA 8 ADITYA DAVE DEEPAK KUMAR DAVE DADAI ROAD VARKANA 9 ADITYA DIXIT SHYAM SUNDER DIXIT BHOLE NATH IRON, BHAGWAN DAS MARKET, JALCHAKKI ROAD, KANKROLI 10 AHIR JYOTI SHANKAR LAL SHANKAR LAL DEVIPURA -II, TEH-RASHMI 11 AJAY KUMAR MEENA JEEVA JI MEENA VILLAGE KODIYA KHET POST BARAPAL TEH.GIRWA 12 AJAY KUMAR SEN SURESH CHANDRA SEN NAI VILL- JAISINGHPURA, POST- MUNJWA 13 AKANSHA SINGH RAO BHAGWAT SINGH RAO 21, RESIDENCY ROAD, UDAIPUR 14 AKASH KUMAR MEENA BHIMACHAND MEENA VILL MANAPADA POST KARCHA TEH KHERWARA 15 AKSHAY KALAL LAXMAN LAL KALAL TEHSIL LINK ROAD VPO : GHATOL 16 AKSHAY MEENA SHEESHPAL LB 57, CHITRAKUT NAGAR, BHUWANA, UDAIPUR (RAJ.) - 313001 17 AMAN KUSHWAH UMA SHANKER KUSHWAH ADARSH COLONY KAPASAN 18 AMAN NAMA BHUPENDRA NAMA 305,INDRA COLONEY RAILWAY STATION MALPURA 19 AMBIKA MEGHWAL LACHCHHI RAM MEGHWAL 30 B VIJAY SINGH PATHIK NAGAR SAVINA 20 AMISHA PANCHAL LOKESH PANCHAL VPO - BHILUDA TEH - SAGWARA 21 ANANT NAI RAJU NAI ANANT NAI S/O RAJU NAI VPO-KHODAN TEHSIL-GARHI 22 ANIL JANWA JAGDISH JANWA HOLI CHOUK KHERODA TEH VALLABHNAGAR 23 ANIL JATIYA RATAN LAL JATIYA VILL- JATO KA KHERA, POST- LAXMIPURA 24 ANIL YADAV SHANKAR LAL YADAV VILL-RUNJIYA PO-RUNJIYA 25 ANISHA MEHTA ANIL MEHTA NAYA BAZAAR, KANORE DISTT. -

CRAFT and TRADE in the 18Th CENTURY RAJASTHAN

CRAFT AND TRADE IN THE 18th CENTURY RAJASTHAN ABSTRACT OF THE THESIS SUBMITTED FOR THE AWARD OF THE DEGREE OF Boctor of ^l)ilos;opl)p IN )/er HISTORY ! SO I A. // XATHAR HUSSAIN -- .A Under the Supervision of Prof. B. L. Bhadani Chairman & Coordinator CENTRE OF ADVANCED STUDY DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY ALIGARH MUSLIM UNIVERSITY ALIGARH (INDIA) 2008 ^Ci>Musu m ABSTRACT The study on the 18* century has been attracting the attention of the historians such as Richard Bamett, C.A. Bayly, Muzaffar Alam, Andre Wink, Chetan Singh and others. Two subsequent works on the eastern Rajasthan by S.P. Gupta and Dilbagh Singh and on the northern Rajasthan by G.S.L. Devra have added new dimensions to the whole issue of existing debate on the 18' century, a period of transition in the history of India. Therefore, the importance of the studies on Rajasthan assumes significance which contains a treasure house of archival records, hitherto largely unexplored. My work is consisted of eight chapters with an introduction and conclusion. The first chapter deals with the study of geographical and historical profile of the Rajasthan. The geographical factor such as types of soils, hills, river and vegetation always nourishes the economy of the region. The physical location of Rajasthan had influenced its history to a greater extent. The region bears the physical diversity and we can divide it into two parts namely in the fertile south eastern zone and the thar arid zone. It was bounded by the Mughal subas (provinces) like Multan, Sindh, Delhi, Agra, Gujarat and Malwa. -

Chronicles of Rajputana: the Valour, Sacrifices and Uprightness of Rajputs

Quest Journals Journal of Research in Humanities and Social Science Volume 9 ~ Issue 8 (2021)pp: 15-39 ISSN(Online):2321-9467 www.questjournals.org Research Paper Chronicles of Rajputana: the Valour, Sacrifices and uprightness of Rajputs Suman Lakhani ABSTRACT Many famous kings and emperors have ruled over Rajasthan. Rajasthan has seen the grandeur of the Rajputs, the gallantry of the Mughals, and the extravagance of Jat monarchs. None the less history of Rajasthan has been shaped and molded to fit one typical school of thought but it holds deep secrets and amazing stories of splendors of the past wrapped in various shades of mysteries stories. This paper is an attempt to try and unearth the mysteries of the land of princes. KEYWORDS: Rajput, Sesodias,Rajputana, Clans, Rana, Arabs, Akbar, Maratha Received 18 July, 2021; Revised: 01 August, 2021; Accepted 03 August, 2021 © The author(s) 2021. Published with open access at www.questjournals.org Chronicles of Rajputana: The Valour, Sacrifices and uprightness of Rajputs We are at a fork in the road in India that we have traveled for the past 150 years; and if we are to make true divination of the goal, whether on the right hand or the left, where our searching arrows are winged, nothing could be more useful to us than a close study of the character and history of those who have held supreme power over the country before us, - the waifs.(Sarkar: 1960) Only the Rajputs are discussed in this paper, which is based on Miss Gabrielle Festing's "From the Land of the Princes" and Colonel James Tod's "Annals of Rajasthan." Miss Festing's book does for Rajasthan's impassioned national traditions and dynastic records what Charles Kingsley and the Rev. -

Government of India Ministry of Human Resource Development Department of School Education and Literacy ***** Minutes of the Meet

Government of India Ministry of Human Resource Development Department of School Education and Literacy ***** Minutes of the meeting of the Project Approval Board held on 14th June, 2018 to consider the Annual Work Plan & Budget (AWP&B) 2018-19 of Samagra Shiksha for the State of Rajasthan. 1. INTRODUCTION The meeting of the Project Approval Board (PAB) for considering the Annual Work Plan and Budget (AWP&B) 2018-19 under Samagra Shiksha for the State of Rajasthan was held on 14-06-2018. The list of participants who attended the meeting is attached at Annexure-I. Sh Maneesh Garg, Joint Secretary (SE&L) welcomed the participants and the State representatives led by Shri Naresh Pal Gangwar, Secretary (Education), Government of Rajasthan and invited them to share some of the initiatives undertaken by the State. 2. INITIATIVES OF THE STATE Adarsh and Utkrisht Vidyalaya Yojana: An Adarsh Vidyalaya (KG/Anganwadi-XII) has been developed in each Gram Panchayat as center of excellence. An Utkrisht Vidyalaya (KG/Anganwadi-VIII) has also been developed in each Gram Panchayat under the mentorship of Adarsh school to ensure quality school coverage for other villages in the Gram Panchayat. Panchayat Elementary Education Officer- Principals of Adarsh school have been designated as ex-officio Panchayat Elementary Education Officer (PEEO) to provide leadership and mentorship to all other government elementary schools in the Gram Panchayat. These PEEOs have been designated as Cluster Resource Centre Facilitator (CRCF) for effective monitoring. Integration of Anganwadi centers with schools- Around 38000 Anganwadi centers have been integrated with schools having primary sections for improving pre-primary education under ECCE program of ICDS. -

Regional Briefing Book

Briefing Book (Updated up to 31st December, 2013) Tight F2 fold in Biotite schist, Dhikan area, Pali district, Rajasthan Geological Survey of India Western Region EXECUTIVE SUMMARY E X E C U T I V E S U M M A R Y 1. All the items proposed for the Field Season 2013-14 were timely initiated under the different Missions. The work is under progress and the assigned targets will be achieved as per schedule. 2. The highlight of work carried out during the third quarter of F.S. 2013-14 includes investigations on copper and associated precious metals in Khera block, and Khera SE block, Mundiyawas-ka-khera area, Alwar district, exploration for basemetal in Nanagwas area, Sikar district, exploration for basemetal in Palaswala ki Dhani Block, Sikar district, Rajasthan and investigation for copper and tungsten in Kamalpura Block of the Pur-Banera Belt, Bhilwara District, Rajasthan. Besides, search for cement grade limestone under Project Industrial, Fertiliser and other Minerals have also yielded significant signatures. 3. Under the item investigation for copper and associated precious metals in Khera Block, Mundiyawas-Khera area, Alwar district, Rajasthan, the borehole KBH-11 (FS 2013-14) commenced on 08.07.2013 and closed at 130.35 m depth on 13.09.2013. It has intersected light grey coloured, fine grained, hard, compact siliceous rock with occasional cherty quartzite and scapolite rich bands (meta volcano sedimentary rock). The borehole intersected sulphides manifested in the form of foliation parallel fine disseminations of arsenopyrite and fracture / vein filled coarse grained chalcopyrite with minor pyrrhotite from 44.55 m depth onwards with intermittent rich zones between 45.25 m & 49.80 m (4.55 m), 58.70 m & 63.25 m (4.55 m) Cu (V.E.) = 0.8-1.0% along the borehole. -

Asoka's Dhamma

/ ASORA'S DIIAMMA - Ninnal C. Sinha A soka's place is second in the history of Dhamma, second only to ~he founder, Gautama Siddhartha the Buddha. Both Theravada (Southern Buddhist) and Mahayana (Northern Buddhist) traditions agree on this point that Asoka is second to Buddha. Nigrodha or Upagupta, Nagasena or Nagatjuna, both Theravada and Mahayana traditions agree, rank after Asoka. Brahmanical (Hindu) literary works extant bear testimony to Asoka being a great Buddhist. Kalhana in Rajatarangini (12th Cent. A.D.) records Asoka as having adopted the creed of Jina (= Buddha) and as the builder of numerous Stupas and Chaityas. Modem scholars, mostly European, however question the authenticity or purity of Asoka's Dhamma. Critics of Asoka notice the absence of Four Noble Truths, Eight Fold Path and Nirvana from Asoka's Edicts and point to Asoka's mention of Svaga (Svarga) or Heaven in the Edicts. Some scholars hint that Asoka's toleration policy was to accommodate Brahmanical faith while others label Asoka's Dhamma as his invention. In my submission Asoka was a Buddhist first and a Buddhist last. Asoka's own words, that is, Asoka's Edicts substantiate this finding. Inscriptions of Asoka were read and translated by pioneer scholars like Senart, Hultzsch, Bhandarkar, Barua and Woolner. I 5 cannot claim competence to improve on their work and extract mainly from the literal translation of Hultzsch (Corpus Inscriptionum Indicarum: Volume I, London 1925). This ensures that I do not read my own meaning into any word of Asoka. For the same reason I use already done English translation ofPali/Sanskrit texts. -

State Specific Report on Visit to Anganwadi Centres(2017-18)

Visit to Anganwadi Centres- State Specific Report (2017-18) Central Monitoring Unit, Monitoring & Evaluation Division National Institute of Public Cooperation and Child Development 5, Siri Institutional Area, Hauz Khas, New Delhi – 110016 Visit to Anganwadi Centres- State Specific Report (2017-18) List of Contents Page No. Abbreviations 1 Number of AWCs Visited during 2017-18 2 Total 3-5 Andhra Pradesh 6-7 Arunachal Pradesh 8-9 Assam 10-11 Bihar 12-13 Haryana 14-15 Jammu & Kashmir 16-17 Jharkhand 18-19 Karnataka 20-21 Kerala 22-23 Madhya Pradesh 24-25 Maharashtra 26-27 Manipur 28-29 Meghalaya 30-31 Nagaland 32-33 Puducherry 34-35 Rajasthan 36-37 Tamil Nadu 38-39 Telangana 40-41 Tripura 42-43 Uttar Pradesh 44-45 West Bengal 46-47 Major Observations and Recommendations 48-80 Annexure 81-189 Visit to Anganwadi Centres- State Specific Report (2017-18) ANM Auxiliary Nurse Midwife AWC Anganwadi Centre AWW Anganwadi Worker BRGF Backward Regions Grant Fund CSR Corporate Social Responsibility GOI Government of India GOVT. Government HCM Hot cooked Meal ICDS Integrated Child Development Services MGNREGA Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Act MLALAD Member of Legislative Assembly Local area Development MPLAD Members of Parliament Local Area Development MSDP Multi Sectoral Development Programme MS Morning Snacks NRC Nutrition Rehabilitation Centre P&LM Pregnant Women & Lactating Mother PHC Primary Health Centre PRI Panchayti Raj Institution PSE Pre School Education RIDF Rural Infrastructure Development Fund SN Supplementary Nutrition THR Take Home Ration UT Union Territory WHO World Health Organization 1 Visit to Anganwadi Centres- State Specific Report (2017-18) Number of Anganwadi Centres visited in the year 2017-18 S.No Name of the No. -

Rajasthan, Maharashtra, Jammu & Kashmir, Puducherry, and Andaman & Nicobar Islands)

Directorate General NDRF & Civil Defence (Fire) Ministry of Home Affairs East Block 7, Level 7, NEW DELHI, 110066, Fire Hazard and Risk Analysis in the Country for Revamping the Fire Services in the Country Final Report – State Wise Risk Assessment, Infrastructure and Institutional Assessment of Pilot States (Delhi, Rajasthan, Maharashtra, Jammu & Kashmir, Puducherry, and Andaman & Nicobar Islands) December 2011 Submitted by RMSI A-8, Sector 16 Noida 201301, INDIA Tel: +91-120-251-1102, 2101 Fax: +91-120-251-1109, 0963 www.rmsi.com Contact: Sushil Gupta General Manager, Risk Modeling and Insurance Email:[email protected] Fire-Risk and Hazard analysis in the Country Table of Contents Table of Contents .................................................................................................................. 2 List of Figures ....................................................................................................................... 5 List of Tables ........................................................................................................................ 7 Acknowledgements ............................................................................................................. 10 Executive Summary ............................................................................................................ 11 1 Introduction .................................................................................................................. 20 1.1 Background.......................................................................................................... -

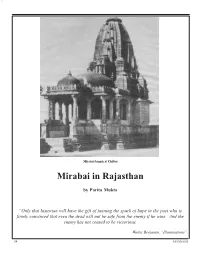

Mirabai in Rajasthan

Mirabai temple at Chittor Mirabai in Rajasthan by Parita Mukta “Only that historian will have the gift of fanning the spark of hope in the past who is firmly convinced that even the dead will not be safe from the enemy if he wins. And the enemy has not ceased to be victorious. Walter Benjamin, “Illuminations” 94 MANUSHI THE legend of Mira, the sixteenth century Rathori princess who took to the life of an itinerant singer, has it that on more than one occasion, she survived attempts on her life by the ruling Sisodiya family of Mewar into which she was married. That Mira, who rejected marriage to the Sisodiya prince and declared her love for Krishna, was able to withstand these threats to her life within her own lifetime is remarkable enough. What is even more remarkable is that the memory of Mira has been kept safe and has continued to be evoked through the centuries of Sisodiya rule, in the midst of repression by the Rajput rulers. There has been a systematic attempt by the Rajput princely family, and more generally the Rajput community in Rajasthan, to blot out the name of Mira within its own social fabric and within the society over which it held Women bhajniks in village Chandravads, district Jamnagar, Saurashtra power. This was demonstrated to me time and again by the various people I spoke you now.” experiences recounted, that those who to and questioned in my attempt to Similar to the experience of Bhattnagarji were tied in a dependency, in different reconstruct a social history of Mira. -

Dr Neekee Chaturvedi

Curriculum Vitae Dr Neekee Chaturvedi Associate Professor Department of History and Indian Culture University of Rajasthan, Jaipur [email protected] 91-9414796730 _____________________________________________________________________________________ ___________________________________________________________________________________ Education B. A. (History, Political Science, Sociology) 1995, University Maharani College, University of Rajasthan M. A. (History) 1997, University of Rajasthan, Gold Medalist M. Phil. 2001, University of Rajasthan, I Position Ph.D., 2008, University of Rajasthan, Thesis: ‘A Historical and Cultural Study of the Suttanipãta ’ NET, December 1996, UGC Diploma in Indian Culture, University of Rajasthan, I Position Diploma in French, 1995, University of Rajasthan, Honours Diploma in German, 1998, University of Rajasthan, Honours 1 Academic Employment 30 November 1998 - 9 December 2013 (15 years) – UG and PG teaching as Permanent Faculty of Directorate of College Education, Rajasthan 09 December 2013 – 19 May 2018 - UG and PG teaching as Assistant Professor, Department of History and Indian Culture, University of Rajasthan 19 May 2018- Continuing – Associate Professor, Department of History and Indian Culture, University of Rajasthan Total Teaching Experience – More than 19 years Research and Teaching Interests Early Buddhism Ancient India Gender issues Folk Traditions of Rajasthan Historiography Research Projects 1. Buddhist Meditation: UGC 2010 - Rs 95,000/ - Classical and Modern 2012 Interpretation 2. Engaging Bishnoi SAARC Cultural 2014 -16 $3000 Community for Cultural Centre, Sri Tourism in Rajasthan Lanka 3. Continuty and Change in a ICSSR (in 2018 Rs 2 Trans -Himalayan Buddhist collaboration) onwards 15 ,00 ,000/ - Community : Socio- economic Study of Four Monasteries of Spiti, Himachal Pradesh Scholarships/Medals/Prizes National Talent Search Scholar University Gold Medal and Jyotirmoy Ghosh Gold Medal for obtaining highest marks in M. -

Briefing Book (Updated up to 30Th June, 2012)

Briefing Book (Updated up to 30th June, 2012) Geological Survey of India Western Region EXECUTIVE SUMMARY EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 1. Field Season Programme for the Field Season 2012 – 13 has been initiated and the Field officers have already taken reconnoitory traverses and in most cases finalized the steps for execution of the programme. The project execution is progressing as per the prorate. 2. Work in the Mundiyawas Khera copper prospect continues to give significant results. The possibility of the prospect to become one of the largest deposit in Alwar Basin and of whole of Rajasthan still holds good. 3. Based on the encouraging analytical results of 100 m X 100 m surface grid samples, subsurface probing has been initiated in Karoi area (an outcome of NGCM work) for search of copper. Surface mineralization nature has already indicated the strike extension of the prospect for more than a kilometer with bornite as the primary sulphide phase associated with chalcopyrite. The prospect is likely to yield encouraging values for copper at subsurface. 4. All the items programmed for the Field Season 2012 – 13 have been initiated. Fieldwork have ben initiated for all the items under Mission – I and Mission – II. Fieldwork have been initiated for some items of Mission – IV. Fieldwork for the remaining items of Mission – IV will be taken up very soon. 5. For the sponsored projects of Engineering Geology, interaction is going on with the Project Authorities and the programmes will be executed very soon after signing of MOU. 6. All the officers of 35th OCG Batch joining Western Region have initiated their project work of OCG Curriculam in the respective items where they will be associated during the Field Season 2012 – 13.