Mami Abstracts 5 26 20 V5

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Indian and Polish Film Festivals

Indian and Polish film festivals articles.latimes.com /2009/apr/16/entertainment/et-screening16 New films from India and Poland are highlighted in the seventh annual Indian Film Festival of Los Angeles and the 10th Polish Film Festival. The Indian Film Festival, which runs Tuesday through April 26, includes five feature films making their world premiere, five making their U.S. premiere and another five making their L.A. debut. The festivities begin with the world premiere of Anand Surapar's "The Fakir of Venice" at the ArcLight Hollywood Cinemas. Ani Kapoor of "Slumdog Millionaire" will also be saluted during the festival with screenings of two of his classic films and the premiere of the English-language version of 2007's "Gandhi, My Father," which he produced. www.indianfilmfestival.org The Polish Film Festival has its gala opening Wednesday at the Egyptian Theatre in Hollywood with a screening of "Perfect Guy for My Girl." It continues through May 3 at Laemmle's Sunset 5 Theatre and other venues in Los Angeles and Orange counties. www .polishfilmla.org -- French composers Two of the late Maurice Jarre's great scores -- for 1985's "Witness" and 1986's "The Mosquito Coast" -- are featured in the American Cinemathque's weekend retrospective "The French Music Composers Go to Hollywood" at the Aero Theatre in Santa Monica. The beautiful music begins tonight with a double bill of 1981's "Woman Next Door," composed by Georges Delerue, and 2001's "Read My Lips," scored by Alexandre Desplat. Michel Legrand supplied the score for 1968's "The Thomas Crown Affair," screening Friday with Michel Colombier's score for 1984's "Against All Odds." The Jarre double feature is scheduled for Saturday. -

Michael Powell and Emeric Pressburger, a MATTER of LIFE and DEATH/ STAIRWAY to HEAVEN (1946, 104 Min)

December 8 (XXXI:15) Michael Powell and Emeric Pressburger, A MATTER OF LIFE AND DEATH/ STAIRWAY TO HEAVEN (1946, 104 min) (The version of this handout on the website has color images and hot urls.) Written, Produced and Directed by Michael Powell & Emeric Pressburger Music by Allan Gray Cinematography by Jack Cardiff Film Edited by Reginald Mills Camera Operator...Geoffrey Unsworth David Niven…Peter Carter Kim Hunter…June Robert Coote…Bob Kathleen Byron…An Angel Richard Attenborough…An English Pilot Bonar Colleano…An American Pilot Joan Maude…Chief Recorder Marius Goring…Conductor 71 Roger Livesey…Doctor Reeves Robert Atkins…The Vicar Bob Roberts…Dr. Gaertler Hour of Glory (1949), The Red Shoes (1948), Black Narcissus Edwin Max…Dr. Mc.Ewen (1947), A Matter of Life and Death (1946), 'I Know Where I'm Betty Potter…Mrs. Tucker Going!' (1945), A Canterbury Tale (1944), The Life and Death of Abraham Sofaer…The Judge Colonel Blimp (1943), One of Our Aircraft Is Missing (1942), 49th Raymond Massey…Abraham Farlan Parallel (1941), The Thief of Bagdad (1940), Blackout (1940), The Robert Arden…GI Playing Bottom Lion Has Wings (1939), The Edge of the World (1937), Someday Robert Beatty…US Crewman (1935), Something Always Happens (1934), C.O.D. (1932), Hotel Tommy Duggan…Patrick Aloyusius Mahoney Splendide (1932) and My Friend the King (1932). Erik…Spaniel John Longden…Narrator of introduction Emeric Pressburger (b. December 5, 1902 in Miskolc, Austria- Hungary [now Hungary] —d. February 5, 1988, age 85, in Michael Powell (b. September 30, 1905 in Kent, England—d. Saxstead, Suffolk, England) won the 1943 Oscar for Best Writing, February 19, 1990, age 84, in Gloucestershire, England) was Original Story for 49th Parallel (1941) and was nominated the nominated with Emeric Pressburger for an Oscar in 1943 for Best same year for the Best Screenplay for One of Our Aircraft Is Writing, Original Screenplay for One of Our Aircraft Is Missing Missing (1942) which he shared with Michael Powell and 49th (1942). -

Music Quiz Questions

Music Quiz Questions Check the box for all answers or click on each question for its answer. New! is an addition in the last month. 157. Though denied by its author as the source of his inspiration, what musical work has strong resemblance to the story of a mythical village called Germelshausen that fell under a curse and appears for only one day every century? Brigadoon by Alan Jay Lerner and music by Frederick Loewe The story involves two American tourists who stumble upon Brigadoon, a mysterious Scottish village that appears for only one day every hundred years. Tommy, one of the tourists, falls in love with Fiona, a young woman from Brigadoon. Lerner, however, denied that he had based the book on an older story and stated that he didn't learn of the existence of the Germelshausen story until after he had completed the first draft of Brigadoon. 156. In December 1971, Frank Zappa and The Mothers of Invention were playing in a concert when the casino venue they were in caught fire due to an over-zealous member of the audience firing a a flare gun into the rattan covered ceiling. This is the true origin story of what rock classic? "Smoke on the Water" by Deep Purple The resulting fire destroyed the entire casino complex, along with all the Mothers' equipment. The "smoke on the water" that became the title of the song (credited to bass guitarist Roger Glover, who related how the title occurred to him when he suddenly woke from a dream a few days later) referred to the smoke from the fire spreading over Lake Geneva from the burning casino as the members of Deep Purple watched the fire from their hotel. -

OPERATIONAL EBIT INCREASED 217% to SEK 396 MILLION

THQ NORDIC AB (PUBL) REG NO.: 556582-6558 EXTENDED FINANCIAL YEAR REPORT • 1 JAN 2018 – 31 MAR 2019 OPERATIONAL EBIT INCREASED 217% to SEK 396 MILLION JANUARY–MARCH 2019 JANUARY 2018–MARCH 2019, 15 MONTHS (Compared to January–March 2018) (Compared to full year 2017) > Net sales increased 158% to SEK 1,630.5 m > Net sales increased to SEK 5,754.1 m (507.5). (632.9). > EBITDA increased to SEK 1,592.6 m (272.6), > EBITDA increased 174% to SEK 618.6 m (225.9), corresponding to an EBITDA margin of 28%. corresponding to an EBITDA margin of 38%. > Operational EBIT increased to SEK 897.1 m > Operational EBIT increased 217% to SEK 395.9 m (202.3) corresponding to an Operational EBIT (124.9) corresponding to an Operational EBIT margin of 16%. margin of 24%. > Cash flow from operating activities amounted > Cash flow from operating activities amounted to SEK 1,356.4 m (179.1). to SEK 777.2 m (699.8). > Earnings per share was SEK 4.68 (1.88). > Earnings per share was SEK 1.10 (1.02). > As of 31 March 2019, cash and cash equivalents were SEK 2,929.1 m. Available cash including credit facilities was SEK 4,521.1 m. KEY PERFORMANCE INDICATORS, Jan-Mar Jan-Mar Jan 2018- Jan-Dec GROUP 2019 2018 Mar 2019 2017 Net sales, SEK m 1,630.5 632.9 5,754.1 507.5 EBITDA, SEK m 618.6 225.9 1,592.6 272.6 Operational EBIT, SEK m 395.9 124.9 897.1 202.3 EBIT, SEK m 172.0 107.3 574.6 188.2 Profit after tax , SEK m 103.0 81.1 396.8 139.2 Cash flow from operating activities, SEK m 777.2 699.8 1,356.4 179.1 Sales growth, % 158 673 1,034 68 EBITDA margin, % 38 36 28 54 Operational EBIT margin, % 24 20 16 40 Throughout this report, the extended financial year 1 January 2018 – 31 March 2019 is compared with the financial year 1 January – 31 December 2017. -

Summer Classic Film Series, Now in Its 43Rd Year

Austin has changed a lot over the past decade, but one tradition you can always count on is the Paramount Summer Classic Film Series, now in its 43rd year. We are presenting more than 110 films this summer, so look forward to more well-preserved film prints and dazzling digital restorations, romance and laughs and thrills and more. Escape the unbearable heat (another Austin tradition that isn’t going anywhere) and join us for a three-month-long celebration of the movies! Films screening at SUMMER CLASSIC FILM SERIES the Paramount will be marked with a , while films screening at Stateside will be marked with an . Presented by: A Weekend to Remember – Thurs, May 24 – Sun, May 27 We’re DEFINITELY Not in Kansas Anymore – Sun, June 3 We get the summer started with a weekend of characters and performers you’ll never forget These characters are stepping very far outside their comfort zones OPENING NIGHT FILM! Peter Sellers turns in not one but three incomparably Back to the Future 50TH ANNIVERSARY! hilarious performances, and director Stanley Kubrick Casablanca delivers pitch-dark comedy in this riotous satire of (1985, 116min/color, 35mm) Michael J. Fox, Planet of the Apes (1942, 102min/b&w, 35mm) Humphrey Bogart, Cold War paranoia that suggests we shouldn’t be as Christopher Lloyd, Lea Thompson, and Crispin (1968, 112min/color, 35mm) Charlton Heston, Ingrid Bergman, Paul Henreid, Claude Rains, Conrad worried about the bomb as we are about the inept Glover . Directed by Robert Zemeckis . Time travel- Roddy McDowell, and Kim Hunter. Directed by Veidt, Sydney Greenstreet, and Peter Lorre. -

Nicole Vickery Thesis (PDF 10MB)

ENGAGING IN ACTIVITIES: THE FLOW EXPERIENCE OF GAMEPLAY Nicole E. M. Vickery Bachelor of Games and Interactive Entertainment, Bachelor of Information Technology (First Class Honours) Submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy School of Electrical Engineering and Computer Science Science and Engineering Faculty Queensland University of Technology 2019 Keywords Videogames; Challenge; Activities; Gameplay; Play; Activity Theory; Dynamics; Flow; Immersion; Game design; Conflict; Narrative. i Abstract Creating better player experience (PX) is dependent upon understanding the act of gameplay. The aim of this thesis is to develop an understanding of enjoyment in dynamics actions in-game. There are few descriptive works that capture the actions of players while engaging in playing videogames. Emerging from this gap is our concept of activities, which aims to help describe how players engage in both game-directed (ludic), and playful (paidic) actions in videogames. Enjoyment is central to the player experience of videogames. This thesis utilises flow as a model of enjoyment in games. Flow has been used previously to explore enjoyment in videogames. However, flow has rarely been used to explore enjoyment of nuanced gameplay behaviours that emerge from in-game activities. Most research that investigates flow in videogames is quantitative; there is little qualitative research that describes ‘how’ or ‘why’ players experience flow. This thesis aims to fill this gap by firstly understanding how players engage in activities in games, and then investigating how flow is experience based on these activities. In order to address these broad objectives, this thesis includes three qualitative studies that were designed to create an understanding of the relationship between activities and flow in games. -

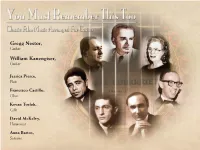

Gregg Nestor, William Kanengiser

Gregg Nestor, Guitar William Kanengiser, Guitar Jessica Pierce, Flute Francisco Castillo, Oboe Kevan Torfeh, Cello David McKelvy, Harmonica Anna Bartos, Soprano Executive Album Producers for BSX Records: Ford A. Thaxton and Mark Banning Album Produced by Gregg Nestor Guitar Arrangements by Gregg Nestor Tracks 1-5 and 12-16 Recorded at Penguin Recording, Eagle Rock, CA Engineer: John Strother Tracks 6-11 Recorded at Villa di Fontani, Lake View Terrace, CA Engineers: Jonathan Marcus, Benjamin Maas Digitally Edited and Mastered by Jonathan Marcus, Orpharian Recordings Album Art Direction: Mark Banning Mr. Nestor’s Guitars by Martin Fleeson, 1981 José Ramirez, 1984 & Sérgio Abreu, 1993 Mr. Kanengiser’s Guitar by Miguel Rodriguez, 1977 Special Thanks to the composer’s estates for access to the original scores for this project. BSX Records wishes to thank Gregg Nestor, Jon Burlingame, Mike Joffe and Frank K. DeWald for his invaluable contribution and oversight to the accuracy of the CD booklet. For Ilaine Pollack well-tempered instrument - cannot be tuned for all keys assuredness of its melody foreshadow the seriousness simultaneously, each key change was recorded by the with which this “concert composer” would approach duo sectionally, then combined. Virtuosic glissando and film. pizzicato effects complement Gold's main theme, a jaunty, kaleidoscopic waltz whose suggestion of a Like Korngold, Miklós Rózsa found inspiration in later merry-go-round is purely intentional. years by uniting both sides of his “Double Life” – the title of his autobiography – in a concert work inspired by his The fanfare-like opening of Alfred Newman’s ALL film music. Just as Korngold had incorporated themes ABOUT EVE (1950), adapted from the main title, pulls us from Warner Bros. -

Television Academy Awards

2021 Primetime Emmy® Awards Ballot Outstanding Music Composition For A Series (Original Dramatic Score) The Alienist: Angel Of Darkness Belly Of The Beast After the horrific murder of a Lying-In Hospital employee, the team are now hot on the heels of the murderer. Sara enlists the help of Joanna to tail their prime suspect. Sara, Kreizler and Moore try and put the pieces together. Bobby Krlic, Composer All Creatures Great And Small (MASTERPIECE) Episode 1 James Herriot interviews for a job with harried Yorkshire veterinarian Siegfried Farnon. His first day is full of surprises. Alexandra Harwood, Composer American Dad! 300 It’s the 300th episode of American Dad! The Smiths reminisce about the funniest thing that has ever happened to them in order to complete the application for a TV gameshow. Walter Murphy, Composer American Dad! The Last Ride Of The Dodge City Rambler The Smiths take the Dodge City Rambler train to visit Francine’s Aunt Karen in Dodge City, Kansas. Joel McNeely, Composer American Gods Conscience Of The King Despite his past following him to Lakeside, Shadow makes himself at home and builds relationships with the town’s residents. Laura and Salim continue to hunt for Wednesday, who attempts one final gambit to win over Demeter. Andrew Lockington, Composer Archer Best Friends Archer is head over heels for his new valet, Aleister. Will Archer do Aleister’s recommended rehabilitation exercises or just eat himself to death? JG Thirwell, Composer Away Go As the mission launches, Emma finds her mettle as commander tested by an onboard accident, a divided crew and a family emergency back on Earth. -

At Powell Hall

GROUPS WELCOME AT POWELL HALL 2017 2018 GROUP SALES GUIDE SEASON slso.org/groupsI 314-286-4155 GROUPS ENJOY FIVE-STAR BENEFITS PERSONALIZED SERVICE Receive one-on-one, personalized service for all your group needs. From seat selection to performance suggestions to local restaurant recommendations, we’re ready to assist with planning your next visit to Powell Hall! SAVINGS Enjoy up to 20%* o the single ticket price when you bring 10 or more people. FREE BUS PARKING Parking, map and transportation information included with all group orders. PRIORITY SEATING Get the best seats for a great price! Group reservations can be made in advance of OUR FAMILY IS YOUR FAMILY public on-sale dates. PRE-CONCERT CONVERSATIONS Whether you’ve been part of the musical tradition or joining us for the first time, Even great music-making profits from an introduction. Enjoy FREE Pre-Concert we welcome you and your neighbors, friends, colleagues or students to experience Conversations before every SLSO classical concert. Music Director David Robertson the incomparable Musical Spirit of the second oldest orchestra in the country, and our guest artists participate in many of these conversations. your St. Louis Symphony Orchestra, in our beloved home of Powell Hall. Bring your group of 10 or more and save up to 20%. These musical oerings are just the start SPONSORED BY of making memories with us this upcoming season! THE SLSO SPECIALIZES IN HOSTING GROUPS: ENHANCE YOUR EXPERIENCE Corporations Employee Outings Schools + Universities Social + Professional Clubs SHUTTLE SERVICE Attraction + Performance Tour Groups Convenient transportation from West County is available for our Friday morning Senior + Youth Groups Coee Concerts. -

Lister); an American Folk Rhapsody Deutschmeister Kapelle/JULIUS HERRMANN; Band of the Welsh Guards/Cap

Guild GmbH Guild -Light Catalogue Bärenholzstrasse 8, 8537 Nussbaumen, Switzerland Tel: +41 52 742 85 00 - e-mail: [email protected] CD-No. Title Track/Composer Artists GLCD 5101 An Introduction Gateway To The West (Farnon); Going For A Ride (Torch); With A Song In My Heart QUEEN'S HALL LIGHT ORCHESTRA/ROBERT FARNON; SIDNEY TORCH AND (Rodgers, Hart); Heykens' Serenade (Heykens, arr. Goodwin); Martinique (Warren); HIS ORCHESTRA; ANDRE KOSTELANETZ & HIS ORCHESTRA; RON GOODWIN Skyscraper Fantasy (Phillips); Dance Of The Spanish Onion (Rose); Out Of This & HIS ORCHESTRA; RAY MARTIN & HIS ORCHESTRA; CHARLES WILLIAMS & World - theme from the film (Arlen, Mercer); Paris To Piccadilly (Busby, Hurran); HIS CONCERT ORCHESTRA; DAVID ROSE & HIS ORCHESTRA; MANTOVANI & Festive Days (Ancliffe); Ha'penny Breeze - theme from the film (Green); Tropical HIS ORCHESTRA; L'ORCHESTRE DEVEREAUX/GEORGES DEVEREAUX; (Gould); Puffin' Billy (White); First Rhapsody (Melachrino); Fantasie Impromptu in C LONDON PROMENADE ORCHESTRA/ WALTER COLLINS; PHILIP GREEN & HIS Sharp Minor (Chopin, arr. Farnon); London Bridge March (Coates); Mock Turtles ORCHESTRA; MORTON GOULD & HIS ORCHESTRA; DANISH STATE RADIO (Morley); To A Wild Rose (MacDowell, arr. Peter Yorke); Plink, Plank, Plunk! ORCHESTRA/HUBERT CLIFFORD; MELACHRINO ORCHESTRA/GEORGE (Anderson); Jamaican Rhumba (Benjamin, arr. Percy Faith); Vision in Velvet MELACHRINO; KINGSWAY SO/CAMARATA; NEW LIGHT SYMPHONY (Duncan); Grand Canyon (van der Linden); Dancing Princess (Hart, Layman, arr. ORCHESTRA/JOSEPH LEWIS; QUEEN'S HALL LIGHT ORCHESTRA/ROBERT Young); Dainty Lady (Peter); Bandstand ('Frescoes' Suite) (Haydn Wood) FARNON; PETER YORKE & HIS CONCERT ORCHESTRA; LEROY ANDERSON & HIS 'POPS' CONCERT ORCHESTRA; PERCY FAITH & HIS ORCHESTRA; NEW CONCERT ORCHESTRA/JACK LEON; DOLF VAN DER LINDEN & HIS METROPOLE ORCHESTRA; FRANK CHACKSFIELD & HIS ORCHESTRA; REGINALD KING & HIS LIGHT ORCHESTRA; NEW CONCERT ORCHESTRA/SERGE KRISH GLCD 5102 1940's Music In The Air (Lloyd, arr. -

Click to Download

v8n4 covers.qxd 5/13/03 1:58 PM Page c1 Volume 8, Number 4 Original Music Soundtracks for Movies & Television Action Back In Bond!? pg. 18 MeetTHE Folks GUFFMAN Arrives! WIND Howls! SPINAL’s Tapped! Names Dropped! PLUS The Blue Planet GEORGE FENTON Babes & Brits ED SHEARMUR Celebrity Studded Interviews! The Way It Was Harry Shearer, Michael McKean, MARVIN HAMLISCH Annette O’Toole, Christopher Guest, Eugene Levy, Parker Posey, David L. Lander, Bob Balaban, Rob Reiner, JaneJane Lynch,Lynch, JohnJohn MichaelMichael Higgins,Higgins, 04> Catherine O’Hara, Martin Short, Steve Martin, Tom Hanks, Barbra Streisand, Diane Keaton, Anthony Newley, Woody Allen, Robert Redford, Jamie Lee Curtis, 7225274 93704 Tony Curtis, Janet Leigh, Wolfman Jack, $4.95 U.S. • $5.95 Canada JoeJoe DiMaggio,DiMaggio, OliverOliver North,North, Fawn Hall, Nick Nolte, Nastassja Kinski all mentioned inside! v8n4 covers.qxd 5/13/03 1:58 PM Page c2 On August 19th, all of Hollywood will be reading music. spotting editing composing orchestration contracting dubbing sync licensing music marketing publishing re-scoring prepping clearance music supervising musicians recording studios Summer Film & TV Music Special Issue. August 19, 2003 Music adds emotional resonance to moving pictures. And music creation is a vital part of Hollywood’s economy. Our Summer Film & TV Music Issue is the definitive guide to the music of movies and TV. It’s part 3 of our 4 part series, featuring “Who Scores Primetime,” “Calling Emmy,” upcoming fall films by distributor, director, music credits and much more. It’s the place to advertise your talent, product or service to the people who create the moving pictures. -

Film Music Week 4 20Th Century Idioms - Jazz

Film Music Week 4 20th Century Idioms - Jazz alternative approaches to the romantic orchestra in 1950s (US & France) – with a special focus on jazz... 1950s It was not until the early 50’s that HW film scores solidly move into the 20th century (idiom). Alex North (influenced by : Bartok, Stravinsky) and Leonard Rosenman (influenced by: Schoenberg, and later, Ligeti) are important influences here. Also of note are Georges Antheil (The Plainsman, 1937) and David Raksin (Force of Evil, 1948). Prendergast suggests that in the 30’s & 40’s the films possessed somewhat operatic or unreal plots that didn’t lend themselves to dissonance or expressionistic ideas. As Hollywood moved towards more realistic portrayals, this music became more appropriate. Alex North, leader in a sparser style (as opposed to Korngold, Steiner, Newman) scored Death of a Salesman (image above)for Elia Kazan on Broadway – this led to North writing the Streetcar film score for Kazan. European influences Also Hollywood was beginning to be strongly influenced by European films which has much more adventuresome scores or (often) no scores at all. Fellini & Rota, Truffault & Georges Delerue, Maurice Jarre (Sundays & Cybele, 1962) and later the Professionals, 1966, Ennio Morricone (Serge Leone, jazz background). • Director Frederico Fellini &composer Nino Rota (many examples) • Director François Truffault & composerGeorges Delerue, • Composer Maurice Jarre (Sundays & Cybele, 1962) and later the • Professionals, 1966, Composer- Ennio Morricone (Serge Leone, jazz background). (continued) Also Hollywood was beginning to be strongly influenced by European films which has much more adventuresome scores or (often) no scores at all. Fellini & Rota, Truffault & Georges Delerue, Maurice Jarre (Sundays & Cybele, 1962) and later the Professionals, 1966, Ennio Morricone (Serge Leone, jazz background).