Cintia Luz.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Primulaceae Flora of the Cangas of Serra Dos Carajás, Pará, Brazil: Primulaceae

Rodriguésia 68, n.3 (Especial): 1085-1090. 2017 http://rodriguesia.jbrj.gov.br DOI: 10.1590/2175-7860201768346 Flora das cangas da Serra dos Carajás, Pará, Brasil: Primulaceae Flora of the cangas of Serra dos Carajás, Pará, Brazil: Primulaceae Maria de Fátima Freitas1,2 & Bruna Nunes de Luna1 Resumo Este estudo apresenta as espécies de Primulaceae registradas para as áreas de canga da Serra dos Carajás, estado do Pará, incluindo descrição morfológica, comentários e ilustrações. São registrados dois gêneros e seis espécies para a área de estudo: Clavija lancifolia subsp. chermontiana, C. macrophylla, Cybianthus amplus, C. detergens, C. penduliflorus e Cybianthus sp. 1. Palavras-chave: Myrsinaceae, Theophrastaceae, FLONA Carajás, flora, taxonomia. Abstract This study presents the species of Primulaceae recorded for the cangas of Serra dos Carajás, Pará state, including morphological descriptions, comments and illustrations. Six species representing two genera were recorded in the study area: Clavija lancifolia subsp. chermontiana, C. macrophylla, Cybianthus amplus, C. detergens, C. penduliflorus e Cybianthus sp. 1. Key words: Myrsinaceae, Theophrastaceae, FLONA Carajás, flora, taxonomy. Primulaceae As espécies encontradas na cangas da Serra de Primulaceae apresenta distribuição Carajás caracterizam-se por serem arbusto a pantropical, com aproximadamente 2.500 arvoretas, bissexuais ou unissexuais, com folhas espécies e 58 gêneros (Stevens 2001 em diante) simples, alternas, não estipuladas. Apresentam agrupados em quatro subfamílias: Maesoideae, inflorescências racemosas, flores pediceladas, Myrsinoideae, Primuloideae e Theophrastoideae bractéola única, cálice livre ou fusionado na base (APG IV). Destas, duas ocorrem na Flora do e corola gamopétala. O androceu é tipicamente Brasil, Myrsinoideae e Theophrastoideae, com epipétalo, isostêmone, com estames livres entre 12 gêneros e cerca de 140 espécies (Freitas et si ou unidos em um tubo; estaminódios também al. -

Rediscovery of Cybianthus Froelichii (Primulaceae), an Endangered Species from Brazil

Bol. Mus. Biol. Mello Leitão (N. Sér.) 38(1):31-38. Janeiro-Março de 2016 31 Rediscovery of Cybianthus froelichii (Primulaceae), an endangered species from Brazil Maria de Fátima Freitas1*, Tatiana Tavares Carrijo2 & Bruna Nunes de Luna1 RESUMO: (Redescoberta de Cybianthus froelichii (Primulaceae), uma espécie ameaçada de extinção do Brasil). Uma espécie redescoberta de Cybianthus subgênero Cybianthus é descrita e ilustrada. Cybianthus froelichii é proximamente relacionado à C. cuneifolius, mas se diferencia pelas folhas grandes e flores pistiladas sésseis. Espécie endêmica da Mata Atlântica e considerada ameaçada de extinção. C. froelichii é aqui ilustrada pela primeira vez. Palavras-chave: Mata Atlântica, diversidade, Ericales, Neotrópico, Myrsinoideae. ABSTRACT: A rediscovered species of Cybianthus subgenus Cybianthus is described and illustrated. Cybianthus froelichii is most closely related to C. cuneifolius, but may be distinguished by its large leaves and sessile pistillate flowers. This species is endemic to the Atlantic Forest, Brazil, and is considered endangered. C. froelichii is illustrated here for the first time. Key words: Atlantic Forest, diversity, Ericales, Neotropic, Myrsinoideae. 1 Instituto de Pesquisas Jardim Botânico do Rio de Janeiro, Diretoria de Pesquisas, Rua Pacheco Leão 915, CEP 22460-030, Rio de Janeiro, RJ, Brasil. 2 Universidade Federal do Espírito Santo, Centro de Ciências Agrárias, Departamento de Biologia, Alto Universitário s.n., CEP 29500-000, Alegre, ES, Brasil. *Corresponding author. e-mail: [email protected] -

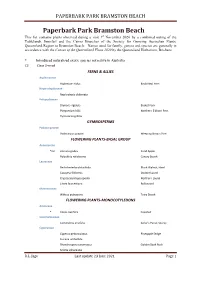

Paperbark Park Bramston Beach

PAPERBARK PARK BRAMSTON BEACH Paperbark Park Bramston Beach This list contains plants observed during a visit 1st November 2020 by a combined outing of the Tablelands, Innisfail and the Cairns Branches of the Society for Growing Australian Plants, Queensland Region to Bramston Beach. Names used for family, genera and species are generally in accordance with the Census of the Queensland Flora 2020 by the Queensland Herbarium, Brisbane. * Introduced naturalised exotic species not native to Australia C3 Class 3 weed FERNS & ALLIES Aspleniaceae Asplenium nidus Birds Nest Fern Nephrolepidaceae Nephrolepis obliterata Polypodiaceae Drynaria rigidula Basket Fern Platycerium hillii Northern Elkhorn Fern Pyrrosia longifolia GYMNOSPERMS Podocarpaceae Podocarpus grayae Weeping Brown Pine FLOWERING PLANTS-BASAL GROUP Annonaceae *C3 Annona glabra Pond Apple Polyalthia nitidissima Canary Beech Lauraceae Beilschmiedia obtusifolia Blush Walnut; Hard Cassytha filiformis Dodder Laurel Cryptocarya hypospodia Northern Laurel Litsea fawcettiana Bollywood Monimiaceae Wilkiea pubescens Tetra Beech FLOWERING PLANTS-MONOCOTYLEDONS Arecaceae * Cocos nucifera Coconut Commelinaceae Commelina ensifolia Sailor's Purse; Scurvy Cyperaceae Cyperus pedunculatus Pineapple Sedge Fuirena umbellata Rhynchospora corymbosa Golden Beak Rush Scleria sphacelata R.L. Jago Last update 23 June 2021 Page 1 PAPERBARK PARK BRAMSTON BEACH Flagellariaceae Flagellaria indica Supplejack Heliconiaceae * Heliconia psittacorum Heliconia Hemerocallidaceae Dianella caerulea var. vannata Blue -

Factors Influencing Density of the Northern Mealy Amazon in Three Forest Types of a Modified Rainforest Landscape in Mesoamerica

VOLUME 12, ISSUE 1, ARTICLE 5 De Labra-Hernández, M. Á., and K. Renton. 2017. Factors influencing density of the Northern Mealy Amazon in three forest types of a modified rainforest landscape in Mesoamerica. Avian Conservation and Ecology 12(1):5. https://doi.org/10.5751/ACE-00957-120105 Copyright © 2017 by the author(s). Published here under license by the Resilience Alliance. Research Paper Factors influencing density of the Northern Mealy Amazon in three forest types of a modified rainforest landscape in Mesoamerica Miguel Ángel De Labra-Hernández 1 and Katherine Renton 2 1Posgrado en Ciencias Biológicas, Instituto de Biología, Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, Mexico City, México, 2Estación de Biología Chamela, Instituto de Biología, Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, Jalisco, México ABSTRACT. The high rate of conversion of tropical moist forest to secondary forest makes it imperative to evaluate forest metric relationships of species dependent on primary, old-growth forest. The threatened Northern Mealy Amazon (Amazona guatemalae) is the largest mainland parrot, and occurs in tropical moist forests of Mesoamerica that are increasingly being converted to secondary forest. However, the consequences of forest conversion for this recently taxonomically separated parrot species are poorly understood. We measured forest metrics of primary evergreen, riparian, and secondary tropical moist forest in Los Chimalapas, Mexico. We also used point counts to estimate density of Northern Mealy Amazons in each forest type during the nonbreeding (Sept 2013) and breeding (March 2014) seasons. We then examined how parrot density was influenced by forest structure and composition, and how parrots used forest types within tropical moist forest. -

Museum of Economic Botany, Kew. Specimens Distributed 1901 - 1990

Museum of Economic Botany, Kew. Specimens distributed 1901 - 1990 Page 1 - https://biodiversitylibrary.org/page/57407494 15 July 1901 Dr T Johnson FLS, Science and Art Museum, Dublin Two cases containing the following:- Ackd 20.7.01 1. Wood of Chloroxylon swietenia, Godaveri (2 pieces) Paris Exibition 1900 2. Wood of Chloroxylon swietenia, Godaveri (2 pieces) Paris Exibition 1900 3. Wood of Melia indica, Anantapur, Paris Exhibition 1900 4. Wood of Anogeissus acuminata, Ganjam, Paris Exhibition 1900 5. Wood of Xylia dolabriformis, Godaveri, Paris Exhibition 1900 6. Wood of Pterocarpus Marsupium, Kistna, Paris Exhibition 1900 7. Wood of Lagerstremia parviflora, Godaveri, Paris Exhibition 1900 8. Wood of Anogeissus latifolia , Godaveri, Paris Exhibition 1900 9. Wood of Gyrocarpus jacquini, Kistna, Paris Exhibition 1900 10. Wood of Acrocarpus fraxinifolium, Nilgiris, Paris Exhibition 1900 11. Wood of Ulmus integrifolia, Nilgiris, Paris Exhibition 1900 12. Wood of Phyllanthus emblica, Assam, Paris Exhibition 1900 13. Wood of Adina cordifolia, Godaveri, Paris Exhibition 1900 14. Wood of Melia indica, Anantapur, Paris Exhibition 1900 15. Wood of Cedrela toona, Nilgiris, Paris Exhibition 1900 16. Wood of Premna bengalensis, Assam, Paris Exhibition 1900 17. Wood of Artocarpus chaplasha, Assam, Paris Exhibition 1900 18. Wood of Artocarpus integrifolia, Nilgiris, Paris Exhibition 1900 19. Wood of Ulmus wallichiana, N. India, Paris Exhibition 1900 20. Wood of Diospyros kurzii , India, Paris Exhibition 1900 21. Wood of Hardwickia binata, Kistna, Paris Exhibition 1900 22. Flowers of Heterotheca inuloides, Mexico, Paris Exhibition 1900 23. Leaves of Datura Stramonium, Paris Exhibition 1900 24. Plant of Mentha viridis, Paris Exhibition 1900 25. Plant of Monsonia ovata, S. -

Diversity and Endemism of Woody Plant Species in the Equatorial Pacific Seasonally Dry Forests

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Springer - Publisher Connector Biodivers Conserv (2010) 19:169–185 DOI 10.1007/s10531-009-9713-4 ORIGINAL PAPER Diversity and endemism of woody plant species in the Equatorial Pacific seasonally dry forests Reynaldo Linares-Palomino Æ Lars Peter Kvist Æ Zhofre Aguirre-Mendoza Æ Carlos Gonzales-Inca Received: 7 October 2008 / Accepted: 10 August 2009 / Published online: 16 September 2009 Ó The Author(s) 2009. This article is published with open access at Springerlink.com Abstract The biodiversity hotspot of the Equatorial Pacific region in western Ecuador and northwestern Peru comprises the most extensive seasonally dry forest formations west of the Andes. Based on a recently assembled checklist of the woody plants occurring in this region, we analysed their geographical and altitudinal distribution patterns. The montane seasonally dry forest region (at an altitude between 1,000 and 1,100 m, and the smallest in terms of area) was outstanding in terms of total species richness and number of endemics. The extensive seasonally dry forest formations in the Ecuadorean and Peruvian lowlands and hills (i.e., forests below 500 m altitude) were comparatively much more species poor. It is remarkable though, that there were so many fewer collections in the Peruvian departments and Ecuadorean provinces with substantial mountainous areas, such as Ca- jamarca and Loja, respectively, indicating that these places have a potentially higher number of species. We estimate that some form of protected area (at country, state or private level) is currently conserving only 5% of the approximately 55,000 km2 of remaining SDF in the region, and many of these areas protect vegetation at altitudes below 500 m altitude. -

Inhibition of Helicobacter Pylori and Its Associated Urease by Two Regional Plants of San Luis Argentina

Int.J.Curr.Microbiol.App.Sci (2017) 6(9): 2097-2106 International Journal of Current Microbiology and Applied Sciences ISSN: 2319-7706 Volume 6 Number 9 (2017) pp. 2097-2106 Journal homepage: http://www.ijcmas.com Original Research Article https://doi.org/10.20546/ijcmas.2017.609.258 Inhibition of Helicobacter pylori and Its Associated Urease by Two Regional Plants of San Luis Argentina A.G. Salinas Ibáñez1, A.C. Arismendi Sosa1, F.F. Ferramola1, J. Paredes2, G. Wendel2, A.O. Maria2 and A.E. Vega1* 1Área Microbiología, Facultad de Química, Bioquímica y Farmacia, Universidad Nacional de San Luis. Ejercito de los Andes 950 Bloque I, Primer piso. CP5700, San Luis, Argentina 2Área de Farmacología y Toxicología, Facultad de Química, Bioquímica y Farmacia, Universidad Nacional de San Luis. Chacabuco y Pedernera. CP5700, San Luis, Argentina *Corresponding author ABSTRACT The search of alternative anti-Helicobacter pylori agents obtained mainly of medicinal plants is a scientific area of great interest. The antimicrobial effects of Litrahea molleoides K e yw or ds and Aristolochia argentina extracts against sensible and resistant H. pylori strains, were Helicobacter pylori, evaluated in vitro. Also, the urease inhibition activity and the effect on the ureA gene Inhibition urease, expression mRNA was evaluated. The L. molleoides and A. argentinae extracts showed Plants . antimicrobial activity against all strains assayed. Regardless of the extract assayed a decrease of viable count of approximately 2 log units on planktonic cell or established Article Info biofilms in H. pylori strains respect to the control was observed (p<0.05). Also, both Accepted: extracts demonstrated strong urease inhibition activity on sensible H. -

Unifying Knowledge for Sustainability in the Western Hemisphere

Inventorying and Monitoring of Tropical Dry Forests Tree Diversity in Jalisco, Mexico Using a Geographical Information System Efren Hernandez-Alvarez, Ph. Dr. Candidate, Department of Forest Biometrics, University of Freiburg, Germany Dr. Dieter R. Pelz, Professor and head of Department of Forest Biometrics, University of Freiburg, Germany Dr. Carlos Rodriguez Franco, International Affairs Specialist, USDA-ARS Office of International Research Programs, Beltsville, MD Abstract—Tropical dry forests in Mexico are an outstanding natural resource, due to the large surface area they cover. This ecosystem can be found from Baja California Norte to Chiapas on the eastern coast of the country. On the Gulf of Mexico side it grows from Tamaulipas to Yucatan. This is an ecosystem that is home to a wide diversity of plants, which include 114 tree species. These species lose their leaves for long periods of time during the year. This plant community prospers at altitudes varying from sea level up to 1700 meters, in a wide range of soil conditions. Studies regarding land attributes with full identification of tree species are scarce in Mexico. However, documenting the tree species composition of this ecosystem, and the environment conditions where it develops is good beginning to assess the diversity that can be found there. A geo- graphical information system overlapping 4 layers of information was applied to define ecological units as a basic element that combines a series of homogeneous biotic and environmental factors that define specific growing conditions for several plant species. These ecological units were sampled to document tree species diversity in a land track of 4662 ha, known as “Arroyo Cuenca la Quebrada” located at Tomatlan, Jalisco. -

Mediterranean Biomes: Evolution of Their Vegetation, Floras, and Climate Philip W

ES47CH17-Rundel ARI 7 October 2016 10:20 Mediterranean Biomes: ANNUAL REVIEWS Further Evolution of Their Vegetation, Click here to view this article's online features: • Download figures as PPT slides Floras, and Climate • Navigate linked references • Download citations • Explore related articles • Search keywords Philip W. Rundel,1 Mary T.K. Arroyo,2 Richard M. Cowling,3 Jon E. Keeley,4 Byron B. Lamont,5 and Pablo Vargas6 1 Department of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology and Institute of the Environment and Sustainability, University of California, Los Angeles, California 90095; email: [email protected] 2 Institute of Ecology and Biodiversity, Department of Ecological Sciences, Facultad de Ciencias, Universidad de Chile, Casilla 653, Santiago, Chile; email: [email protected] 3 Centre for Coastal Palaeosciences, Nelson Mandela Metropolitan University, Port Elizabeth 6031, South Africa; email: [email protected] 4 Sequoia Field Station, Western Ecological Research Center, U.S. Geological Survey, Three Rivers, California 93271; email: [email protected] 5 Department of Environment and Agriculture, Curtin U niversity, Perth, Western Australia 6845, Australia; email: [email protected] 6 Department of Biodiversity and Conservation, Royal Botanical Garden of Madrid, CSIC, 28014 Madrid, Spain; email: [email protected] Annu. Rev. Ecol. Evol. Syst. 2016. 47:383–407 Keywords First published online as a Review in Advance on mediterranean-type ecosystems, mediterranean climate, fire, evolutionary September 2, 2016 history, southwestern Australia, Cape Region, Mediterranean Basin, The Annual Review of Ecology, Evolution, and California, Chile Systematics is online at ecolsys.annualreviews.org This article’s doi: Abstract 10.1146/annurev-ecolsys-121415-032330 Mediterranean-type ecosystems (MTEs) are located today in southwest- Copyright c 2016 by Annual Reviews. -

Chec List What Survived from the PLANAFLORO Project

Check List 10(1): 33–45, 2014 © 2014 Check List and Authors Chec List ISSN 1809-127X (available at www.checklist.org.br) Journal of species lists and distribution What survived from the PLANAFLORO Project: PECIES S Angiosperms of Rondônia State, Brazil OF 1* 2 ISTS L Samuel1 UniCarleialversity of Konstanz, and Narcísio Department C.of Biology, Bigio M842, PLZ 78457, Konstanz, Germany. [email protected] 2 Universidade Federal de Rondônia, Campus José Ribeiro Filho, BR 364, Km 9.5, CEP 76801-059. Porto Velho, RO, Brasil. * Corresponding author. E-mail: Abstract: The Rondônia Natural Resources Management Project (PLANAFLORO) was a strategic program developed in partnership between the Brazilian Government and The World Bank in 1992, with the purpose of stimulating the sustainable development and protection of the Amazon in the state of Rondônia. More than a decade after the PLANAFORO program concluded, the aim of the present work is to recover and share the information from the long-abandoned plant collections made during the project’s ecological-economic zoning phase. Most of the material analyzed was sterile, but the fertile voucher specimens recovered are listed here. The material examined represents 378 species in 234 genera and 76 families of angiosperms. Some 8 genera, 68 species, 3 subspecies and 1 variety are new records for Rondônia State. It is our intention that this information will stimulate future studies and contribute to a better understanding and more effective conservation of the plant diversity in the southwestern Amazon of Brazil. Introduction The PLANAFLORO Project funded botanical expeditions In early 1990, Brazilian Amazon was facing remarkably in different areas of the state to inventory arboreal plants high rates of forest conversion (Laurance et al. -

ISTA List of Stabilised Plant Names 7Th Edition

ISTA List of Stabilised Plant Names 7th Edition ISTA Nomenclature Committee Chair Dr. M. Schori Published by All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be The International Seed Testing Association (ISTA) reproduced, stored in any retrieval system or transmitted in Richtiarkade 18, CH- 8304 Wallisellen, Switzerland any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without prior ©2021 International Seed Testing Association (ISTA) permission in writing from ISTA. ISBN 978-3-906549-77-4 Valid from: 16.06.2021 ISTA List of Stabilised Plant Names 1st Edition 1966 ISTA Nomenclature Committee Chair: Prof P. A. Linehan 2nd Edition 1983 ISTA Nomenclature Committee Chair: Dr. H. Pirson 3rd Edition 1988 ISTA Nomenclature Committee Chair: Dr. W. A. Brandenburg 4th Edition 2001 ISTA Nomenclature Committee Chair: Dr. J. H. Wiersema 5th Edition 2007 ISTA Nomenclature Committee Chair: Dr. J. H. Wiersema 6th Edition 2013 ISTA Nomenclature Committee Chair: Dr. J. H. Wiersema 7th Edition 2019 ISTA Nomenclature Committee Chair: Dr. M. Schori 7th Edition 2 ISTA List of Stabilised Plant Names Table of Contents A .............................................................................................................................................................. 7 B ............................................................................................................................................................ 21 C ........................................................................................................................................................... -

Gene Flow and Geographic Variation in Natural Populations of Alnus Acumi1'lata Ssp

Rev. Biol. Trop., 47(4): 739-753, 1999 www.ucr.ac.cr www.ots.ac.cr www.ots.duke.edu Gene flow and geographic variation in natural populations of Alnus acumi1'lata ssp. arguta (Fagales: Betulaceae) in Costa Rica and Panama OIman Murillo) and Osear Roeha2 Instituto Tecnológico de Costa Rica, Escuela de Ing. Forestal.Apartado 159 7050 Cartago, Costa Rica. Fax: 591-4182. e-mail: omurillo@itcr.. ac.cr 2 Universidad de Costa Rica, Escuela de Biología, Campus San Pedro, San José, Costa Rica. e-mail: [email protected] Received 16-IX-1998. Corrected 05-IV-1999. Accepted 16-IV-1999 Abstract: Seventeen natural populations in Costa Rica andPanama were used to asses geneflow and geographic patternsof genetic variation in tbis tree species. Gene flow analysis was based on the methods of rare alleles and FST (Index of genetic similarity M), using the only four polymorphic gene loci among 22 investigated (PGI-B, PGM-A, MNR-A and IDH-A). The geographic variation analysiswas based on Pearson 's correlations between four geographic and 14 genetic variables. Sorne evidence of isolation by distance and a weak gene flow among geographic regions was found. Patterns of elinal variation in relation to altitude (r = -0.62 for genetic diversity) and latitude (r = -0.77 for PGI-B3) were also observed, supporting the hypothesis of isolation by distance. No privatealleles were found at the single population level. Key words: Alnus acuminata, isozymes, gene flow, eline, geographic variation, Costa Rica, Panarna. Pollen and seed moverrient among counteract any potential for genetic drift subdivided popuIations in a tree speeies, (Hamrick 1992 in Boshieret al.