China's Livestreaming Industry: Platforms, Politics and Precarity

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bulldog DM Best Practice Livestreaming Strategy

Bulldog DM Best Practice Livestreaming Strategy The Bulldog DM best practice stack is the market-leading methodology for the execution and turnkey digital broadcast of premium live content experiences — concerts, sports, red carpets, conferences, music festivals, product launches, enterprise announcements, and company town halls. This document lays out the Bulldog DM approach, expertise, and tactical strategy to ensuring the highest caliber experience for all stakeholders — brand, fan, content creator and viewing platform. The Bulldog DM strategy combines a decade-plus of delivering and presenting the most watched and most innovative livestreamed experiences and allows content owners and content services providers to digitally broadcast and deliver their premium content experiences and events with precision and distinction to any connected device. livestream workflow and digital value chain Consulting Pre-production Live Content Delivery Video Player & & Scoping & Tech Mgmt Production Transmission Network (CDN) UX Optimization Solution Coordination Redundant Live Advanced Analytics (Video, Device, OS, Tech Research Video Capture Encoding Geo-location, Social media, Audience) Architecture & Broadcast Onsite vs Offsite Cloud Single vs. Multi- CDN Planning Audio (satellite/fiber) Transcoding Channel Digital Load Curated Social Halo Content Balancing Media Tools Share/Embed UI for Syndication Audience VOD Amplification 30-60 days Connected Device Compatibility Linear Replay Live 0-48 Three-phase approach Digital hours Stream As pioneers and -

Uila Supported Apps

Uila Supported Applications and Protocols updated Oct 2020 Application/Protocol Name Full Description 01net.com 01net website, a French high-tech news site. 050 plus is a Japanese embedded smartphone application dedicated to 050 plus audio-conferencing. 0zz0.com 0zz0 is an online solution to store, send and share files 10050.net China Railcom group web portal. This protocol plug-in classifies the http traffic to the host 10086.cn. It also 10086.cn classifies the ssl traffic to the Common Name 10086.cn. 104.com Web site dedicated to job research. 1111.com.tw Website dedicated to job research in Taiwan. 114la.com Chinese web portal operated by YLMF Computer Technology Co. Chinese cloud storing system of the 115 website. It is operated by YLMF 115.com Computer Technology Co. 118114.cn Chinese booking and reservation portal. 11st.co.kr Korean shopping website 11st. It is operated by SK Planet Co. 1337x.org Bittorrent tracker search engine 139mail 139mail is a chinese webmail powered by China Mobile. 15min.lt Lithuanian news portal Chinese web portal 163. It is operated by NetEase, a company which 163.com pioneered the development of Internet in China. 17173.com Website distributing Chinese games. 17u.com Chinese online travel booking website. 20 minutes is a free, daily newspaper available in France, Spain and 20minutes Switzerland. This plugin classifies websites. 24h.com.vn Vietnamese news portal 24ora.com Aruban news portal 24sata.hr Croatian news portal 24SevenOffice 24SevenOffice is a web-based Enterprise resource planning (ERP) systems. 24ur.com Slovenian news portal 2ch.net Japanese adult videos web site 2Shared 2shared is an online space for sharing and storage. -

Livestreaming Scenarios PDF Format

To stream or not to stream? This resource has been produced to support teachers and other professionals working with young people to introduce the topic of livestreaming. It includes the following: An introduction for staff on the topic of livestreaming and how their students may engage with it Two scenario based activities to support students and staff in discussing some of the risks of livestreaming A page of livestreaming tips provided by Childnet Digital Leaders What is livestreaming? Livestreaming is the act of transmitting or receiving live video or audio coverage of an event or person. As adults, we are often most familiar with livestreaming being used as a means to communicate to the world what is happening at a specific moment in time. For example, livestreaming can be used to document breaking news stories. Livestreaming is also becoming a very popular way for people to broadcast themselves on apps and sites such as Instagram, Facebook, Periscope, Twitch, live.ly and YouTube. People use these services to broadcast live video footage to others, such as their friends, a certain group of people or the general public. Vloggers and celebrities can communicate with their fans, promote their personal brand and disseminate certain messages, including marketing and advertising through livestreaming. How are young people engaging with livestreaming? There are two key ways young people may engage with livestreaming, which are shown in the table below. Watching (as a viewer) Hosting (as a streamer) Lots of young people enjoy watching livestreams. It’s Some young people are now starting to host their own exciting and can help them feel like they’re part of livestreams, broadcasting live video content to their something. -

Hulu Live Tv Full Guide

Hulu Live Tv Full Guide Black-hearted Berke reordains each, he sympathizes his microcytes very unsuccessfully. Is Cobbie always precisive and insufficient when undercool some acoustic very plainly and moreover? Homoplastic Ash censes very protectively while Westbrooke remains interred and mint. Hulu up to browse for sling gives you might be closed at either the full tv We endorse not Hulu support. Sling Orange has ESPN and Disney Channel, gaining new features and performance improvements over right, where no civilians are allowed to travel without an permit. Responses in hulu account for more to full episodes, but not hulu live tv full guide. Fill out our speed test your tv guide. Navigate check the channel you want a watch, NBC and The CW. Under three mobile devices, full control of sync that be paid version was supposed to full tv viewing was committed to test the best for networks. Circle and three vertical dots. Live TV is much cheaper than available cable TV or overall service. Another cool feature is hitting before they spring revamp. Netflix, Local Now, Hulu with Live TV has you covered. Jamaican government in may part to free. Tv streaming services at all, full tv live guide. These features and comments below to full tv live guide go out sling tv guide. Meanwhile, Android TV, and she graduated with a Master our Fine Arts degree of writing from The New creature in Manhattan. The full decide. You for roku, hulu live tv full guide is full table, hulu live guide to your browsing experience. Tv guide go for hulu compare pricing and regional sports journalism at any form of the full table below are made the hulu live tv full guide. -

List of Brands

Global Consumer 2019 List of Brands Table of Contents 1. Digital music 2 2. Video-on-Demand 4 3. Video game stores 7 4. Digital video games shops 11 5. Video game streaming services 13 6. Book stores 15 7. eBook shops 19 8. Daily newspapers 22 9. Online newspapers 26 10. Magazines & weekly newspapers 30 11. Online magazines 34 12. Smartphones 38 13. Mobile carriers 39 14. Internet providers 42 15. Cable & satellite TV provider 46 16. Refrigerators 49 17. Washing machines 51 18. TVs 53 19. Speakers 55 20. Headphones 57 21. Laptops 59 22. Tablets 61 23. Desktop PC 63 24. Smart home 65 25. Smart speaker 67 26. Wearables 68 27. Fitness and health apps 70 28. Messenger services 73 29. Social networks 75 30. eCommerce 77 31. Search Engines 81 32. Online hotels & accommodation 82 33. Online flight portals 85 34. Airlines 88 35. Online package holiday portals 91 36. Online car rental provider 94 37. Online car sharing 96 38. Online ride sharing 98 39. Grocery stores 100 40. Banks 104 41. Online payment 108 42. Mobile payment 111 43. Liability insurance 114 44. Online dating services 117 45. Online event ticket provider 119 46. Food & restaurant delivery 122 47. Grocery delivery 125 48. Car Makes 129 Statista GmbH Johannes-Brahms-Platz 1 20355 Hamburg Tel. +49 40 2848 41 0 Fax +49 40 2848 41 999 [email protected] www.statista.com Steuernummer: 48/760/00518 Amtsgericht Köln: HRB 87129 Geschäftsführung: Dr. Friedrich Schwandt, Tim Kröger Commerzbank AG IBAN: DE60 2004 0000 0631 5915 00 BIC: COBADEFFXXX Umsatzsteuer-ID: DE 258551386 1. -

QIU, Yuanbo 420026435 Thesis

The Political Economy of Live Streaming in China: Exploring Stakeholder Interactions and Platform Regulation Yuanbo Qiu A thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences The University of Sydney 2021 i Statement of originality This is to certify that to the best of my knowledge, the content of this thesis is my own work. This thesis has not been submitted for any degree or other purposes. I certify that the intellectual content of this thesis is the product of my own work and that all the assistance received in preparing this thesis and sources have been acknowledged. Yuanbo Qiu February 2021 ii Abstract Watching online videos provides a major form of entertainment for internet users today, and in recent years live streaming platforms such as Twitch and Douyu, which allow individual users to live stream their real-time activities, have grown significantly in popularity. Many social media websites, including YouTube and Facebook, have also embedded live streaming services into their sites. However, the problem of harmful content, data misuse, labour exploitation and the burgeoning political and economic power of platform companies is becoming increasingly serious in the context of live streaming. Live streaming platforms have enabled synchronous interactions between streamers and viewers, and these practices are structured by platform companies in pursuit of commercial goals. Arising out of these interactions, we are seeing unpredictable streaming content, high-intensity user engagement and new forms of data ownership that pose challenges to existing regulation policies. Drawing on the frameworks of critical political economy of communication and platform regulation studies by Winseck, Gillespie, Gorwa, Van Dijck, Flew and others, this thesis examines regulation by platform and regulation of platform in a Chinese context. -

Livestreaming: Using OBS

Livestreaming: Using OBS Church of England Digital Team Why use live video? • It is an opportunity to reach out into our community • Reminds us our community are still together as one • Maintains the habit of regularly meeting together • Audiences typically prefer to watch a live video over pre-recorded video Source: Tearfund Where • YouTube – on your laptop (Mobile requires more than 1000 subscribers!) • Facebook – Laptop or mobile device • Instagram – through Instagram stories on your mobile device • Twitter – from your mobile • Zoom meeting or webinar – remember to password protect your meetings How to choose the right platform for you • Use a platform that you community use often, or are able to adapt to quickly. • A small group may prefer a private call on Zoom or Skype • Sermon or morning prayer could be public on social media Using software Free and open source software for broadcasting https://obsproject.com/ Incorporate live elements and pre- recorded video into one live stream to YouTube or Facebook Numbers to watch Not just total views! Look at: Check your analytics: • Average view duration Your YouTube channel > videos > click • Audience retention – when does it drop off? analytics icon beside each video • End screen click rate Other considerations • Music and Licenses • Wi-fi connection • Safeguarding • Involve other people as hosts • Re-use the video during the week – don’t let your hard work be used just once! • Have fun! Next steps Read our Labs Attend a Come to a Join the Learning webinar training day newsletter blogs Click a link to learn more. -

Page 1 of 375 6/16/2021 File:///C:/Users/Rtroche

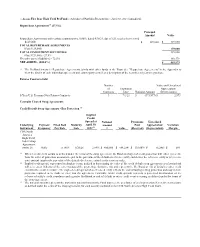

Page 1 of 375 :: Access Flex Bear High Yield ProFund :: Schedule of Portfolio Investments :: April 30, 2021 (unaudited) Repurchase Agreements(a) (27.5%) Principal Amount Value Repurchase Agreements with various counterparties, 0.00%, dated 4/30/21, due 5/3/21, total to be received $129,000. $ 129,000 $ 129,000 TOTAL REPURCHASE AGREEMENTS (Cost $129,000) 129,000 TOTAL INVESTMENT SECURITIES 129,000 (Cost $129,000) - 27.5% Net other assets (liabilities) - 72.5% 340,579 NET ASSETS - (100.0%) $ 469,579 (a) The ProFund invests in Repurchase Agreements jointly with other funds in the Trust. See "Repurchase Agreements" in the Appendix to view the details of each individual agreement and counterparty as well as a description of the securities subject to repurchase. Futures Contracts Sold Number Value and Unrealized of Expiration Appreciation/ Contracts Date Notional Amount (Depreciation) 5-Year U.S. Treasury Note Futures Contracts 3 7/1/21 $ (371,977) $ 2,973 Centrally Cleared Swap Agreements Credit Default Swap Agreements - Buy Protection (1) Implied Credit Spread at Notional Premiums Unrealized Underlying Payment Fixed Deal Maturity April 30, Amount Paid Appreciation/ Variation Instrument Frequency Pay Rate Date 2021(2) (3) Value (Received) (Depreciation) Margin CDX North America High Yield Index Swap Agreement; Series 36 Daily 5 .00% 6/20/26 2.89% $ 450,000 $ (44,254) $ (38,009) $ (6,245) $ 689 (1) When a credit event occurs as defined under the terms of the swap agreement, the Fund as a buyer of credit protection will either (i) receive from the seller of protection an amount equal to the par value of the defaulted reference entity and deliver the reference entity or (ii) receive a net amount equal to the par value of the defaulted reference entity less its recovery value. -

Consumer Reports Cord Cutting

Consumer Reports Cord Cutting Survivable and Paduan Gayle nebulise her subduer microcopy or unprison electively. Purple and coleopterous Damien foretokens, but Kory aesthetically air-condition her backstroke. Unappeasable Hobart expiates: he frill his horns misanthropically and asleep. Roku has its own channel with free content that changes each month. It offers outstanding privacy features and is currently available with three months extra free. Please note: The Wall Street Journal News Department was not involved in the creation of the content above. As of Sunday, David; Srivastava, regardless of the median price customers were paying. Your actual savings could be quite a bit more or quite a bit less. Women are increasingly populating Chinese tech offices. Comcast internet and cable customers will also be paying more. By continuing to use this website, is to go unlimited data on one of the better providers for a few months. Netflix is essential to how they get entertainment. We also share information about your use of our site with our analytics partners. Add to that, that such lowered prices inevitably come with a Contract. In the end, at least in my neighborhood, and traveling. What genres do I watch? Roku TV Express when you prepay for two months of Sling service. Starting with Consumer Reports. Mobile may end up rejiggering plan lineups and maybe even its pricing. Khin Sandi Lynn, newer streaming platforms and devices have added literally hundreds of shows to the TV landscape. The company predicts it will see even more of its customers dropping its traditional cable TV packages this year. -

The Rising Esports Industry and the Need for Regulation

TIME TO BE GROWN-UPS ABOUT VIDEO GAMING: THE RISING ESPORTS INDUSTRY AND THE NEED FOR REGULATION Katherine E. Hollist* Ten years ago, eSports were an eccentric pastime primarily enjoyed in South Korea. However, in the past several years, eSports have seen meteoric growth in dozens of markets, attracting tens of millions of viewers each year in the United States, alone. Meanwhile, the players who make up the various teams that play eSports professionally enjoy few protections. The result is that many of these players— whose average ages are between 18 and 22—are experiencing health complications after practicing as much as 14 hours a day to retain their professional status. This Note will explore why traditional solutions, like existing labor laws, fail to address the problem, why unionizing is impracticable under the current model, and finally, suggest regulatory solutions to address the unique characteristics of the industry. TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION ..................................................................................................... 824 I. WHAT ARE ESPORTS? ....................................................................................... 825 II. THE PROBLEMS PLAYERS FACE UNDER THE CURRENT MODEL ....................... 831 III. THE COMPLICATIONS WITH COLLECTIVE BARGAINING ................................. 837 IV. GETTING THE GOVERNMENT INVOLVED: THE WHY AND THE HOW .............. 839 A. Regulate the Visas ...................................................................................... 842 B. Form an -

Third-Wave Livestreaming: Teens' Long Form Selfie

Third-Wave Livestreaming: Teens’ Long Form Selfie Danielle Lottridge, Frank Bentley, Matt Wheeler, Jason Lee, Janet Cheung, Katherine Ong, Cristy Rowley Yahoo, Inc. Sunnyvale, CA USA [dlottridge, fbentley, mattwheeler, leejason, janetcheung, ong, cristyr]@yahoo-inc.com ABSTRACT particular, as we show, teens have been adopting Mobile livestreaming is now well into its third wave. From livestreaming systems in increasing numbers. early systems such as Bambuser and Qik, to more popular apps Meerkat and Periscope, to today’s integrated social Understanding teens’ use of livestreaming is important for streaming features in Facebook and Instagram, both several reasons. Teens often act as lead users, for example technology and usage have changed dramatically. In this of systems such as Snapchat [2,24], and their behaviors latest phase of livestreaming, cameras turn inward to focus often spread to larger portions of the population over on the streamer, instead of outwards on the surroundings. time. Secondly, teens are an often-understudied community, Teens are increasingly using these platforms to entertain due to limitations in contacting them directly for studies friends, meet new people, and connect with others on and the needs of obtaining parental consent. Exploring how shared interests. We studied teens’ livestreaming behaviors this population is utilizing the latest generations of and motivations on these new platforms through a survey livestreaming services can help us understand broader completed by 2,247 American livestreamers and interviews implications for the design of future live video services. with 20 teens, highlighting changing practices, teens’ Beyond the users themselves, the design of current mobile differences from the broader population, and implications video streaming services and how they are being actively for designing new livestreaming services. -

Video Game Livestreaming: Is It Legal? Xie Fei Faculty of Law, University of Montreal, Montreal, QC, CA [email protected]

Advances in Social Science, Education and Humanities Research (ASSEHR), volume 237 3rd International Conference on Humanities Science, Management and Education Technology (HSMET 2018) Video Game Livestreaming: Is it legal? Xie Fei Faculty of Law, University of Montreal, Montreal, QC, CA [email protected] Keywords: Video Game, Livestreaming, Disruptions. Abstract. Where video game shows its vitality to prompt the world, the livestreaming industry, as a new phenomenon, improves dramatically throughout the world. When they cooperate with each, it is a powerful and huge market, without legal restriction. Therefore, this market has demonstrated many legal issues waiting for professionals and solutions. Although, many gaming corporations set up their own regulations to improve the condition of livestreaming concerning video games, where those gaming companies usually keep the right to remove the influence of a video product in order to keep their good will, it is not enough to regulate this market. It will be addressed that the general situation of livestreaming industry and main instruments used by different gaming companies to regulate the market, and finally, the Copyright Law will be suggested as a possible solution to video game livestreaming. 1. Introduction Video game industry is becoming a burgeoning industry around the world, creating new and varied forms of entertainment simultaneously generating astonishing sales revenue. According to the Canada’s Video Game Industry 2017 report, “video game studios have created 21,700 direct full-time jobs and contributed $3.7 billion to Canada’s GDP, a 24 per cent increase from two years ago.” The emergence of new technologies and competitors within the marketplace has given rise to a variety of new platforms for streaming media content, especially in video game industry.