The Rising Esports Industry and the Need for Regulation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Wetlands Mapper Frequently Asked Questions

Frequently Asked Questions: Wetlands Mapper December 2015 Mapper Content and Display How does the public access the new Mapper? The Wetlands Mapper can be found at: http://www.fws.gov/wetlands/ Does the updated mapper display all wetland polygons from the Wetlands Geodatabase? Yes. All available wetland map data both vector and raster scanned images are on the Mapper. Does the updated mapper display all wetland labels? Yes. Larger polygon labels will display right away. Smaller polygon labels will display at larger scale and appear inside the feature. At what scale do the Wetlands display on screen? Wetlands first display at 1:144,448 scale. The nominal scale for wetland data is 1:12,000 or 1:24,000 although higher resolution is possible. How is the display scale determined? Display scales are pre-determined intervals. The maximum zoom scale is 1:71. ESRI base maps will not display below 1:1,128 scale resolution for the contiguous United States and Puerto Rico, 1:9,028 for Alaska, and 1:4,514 for Hawaii, and the Pacific Trust Islands. Can I minimize the Available Layers Window? Yes. Click on minimize + or – symbol in the upper right hand corner of the Available Layers Window. Can I zoom to locations? How do I find the Pacific Trust Islands? Yes. Use the “Zoom to” tool to quickly go to Alaska, Hawaii, Puerto Rico and Virgin Islands or the Pacific Trust Islands. Enter the name, address, or zip code into the “Find Location” tool to go to a specific location. Latitude and longitude coordinates may also be entered using the format [longitude, latitude]. -

Bulldog DM Best Practice Livestreaming Strategy

Bulldog DM Best Practice Livestreaming Strategy The Bulldog DM best practice stack is the market-leading methodology for the execution and turnkey digital broadcast of premium live content experiences — concerts, sports, red carpets, conferences, music festivals, product launches, enterprise announcements, and company town halls. This document lays out the Bulldog DM approach, expertise, and tactical strategy to ensuring the highest caliber experience for all stakeholders — brand, fan, content creator and viewing platform. The Bulldog DM strategy combines a decade-plus of delivering and presenting the most watched and most innovative livestreamed experiences and allows content owners and content services providers to digitally broadcast and deliver their premium content experiences and events with precision and distinction to any connected device. livestream workflow and digital value chain Consulting Pre-production Live Content Delivery Video Player & & Scoping & Tech Mgmt Production Transmission Network (CDN) UX Optimization Solution Coordination Redundant Live Advanced Analytics (Video, Device, OS, Tech Research Video Capture Encoding Geo-location, Social media, Audience) Architecture & Broadcast Onsite vs Offsite Cloud Single vs. Multi- CDN Planning Audio (satellite/fiber) Transcoding Channel Digital Load Curated Social Halo Content Balancing Media Tools Share/Embed UI for Syndication Audience VOD Amplification 30-60 days Connected Device Compatibility Linear Replay Live 0-48 Three-phase approach Digital hours Stream As pioneers and -

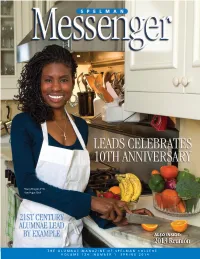

SPRING 2014 SPELMAN Messenger

Stacey Dougan, C’98, Raw Vegan Chef ALSO INSIDE: 2013 Reunion THE ALUMNAE MAGAZINE OF SPELMAN COLLEGE VOLUME 124 NUMBER 1 SPRING 2014 SPELMAN Messenger EDITOR All submissions should be sent to: Jo Moore Stewart Spelman Messenger Office of Alumnae Affairs ASSOCIATE EDITOR 350 Spelman Lane, S.W., Box 304 Joyce Davis Atlanta, GA 30314 COPY EDITOR OR Janet M. Barstow [email protected] Submission Deadlines: GRAPHIC DESIGNER Garon Hart Spring Semester: January 1 – May 31 Fall Semester: June 1 – December 31 ALUMNAE DATA MANAGER ALUMNAE NOTES Alyson Dorsey, C’2002 Alumnae Notes is dedicated to the following: EDITORIAL ADVISORY COMMITTEE • Education Eloise A. Alexis, C’86 • Personal (birth of a child or marriage) Tomika DePriest, C’89 • Professional Kassandra Kimbriel Jolley Please include the date of the event in your Sharon E. Owens, C’76 submission. TAKE NOTE! WRITERS S.A. Reid Take Note! is dedicated to the following Lorraine Robertson alumnae achievements: TaRessa Stovall • Published Angela Brown Terrell • Appearing in films, television or on stage • Special awards, recognition and appointments PHOTOGRAPHERS Please include the date of the event in your J.D. Scott submission. Spelman Archives Julie Yarbrough, C’91 BOOK NOTES Book Notes is dedicated to alumnae authors. Please submit review copies. The Spelman Messenger is published twice a year IN MEMORIAM by Spelman College, 350 Spelman Lane, S.W., We honor our Spelman sisters. If you receive Atlanta, Georgia 30314-4399, free of charge notice of the death of a Spelman sister, please for alumnae, donors, trustees and friends of contact the Office of Alumnae Affairs at the College. -

Optic Gaming Wins Call of Duty® MLG Orlando Open

August 8, 2016 Optic Gaming Wins Call of Duty® MLG Orlando Open NEW YORK--(BUSINESS WIRE)-- The road to the 2016 Call of Duty® World League Championship, Presented by PlayStation® 4 finished its last live qualifying competition yesterday with an epic showdown in Orlando as Optic Gaming won the Call of Duty® MLG Orlando Open. Yesterday's finals completed a thrilling weekend of competition, as eager fans in attendance, online at MLG.tv and other livestreams, and those tuning-in directly through an in-game (BOIII PS4) Live Event Viewer, watched 72 hours of compelling action. Optic Gaming took home the top prize after besting Team Envyus to be the top of more than 100 teams from around the world. Yesterday's exciting tournament also served as the final CWL Pro Points event of the season, as competition now moves to the North American online qualifier as the final stop before the highly anticipated CWL Championship at Call of Duty® XP. At the CWL Championship, 32 teams will play for their share of the biggest single event prize pool in Call of Duty® history, $2 million. With the growth of the Call of Duty World League, Call of Duty esports viewership has increased by more than five times year-over-year to 33 million views of the Stage 1 events this year. The Call of Duty World League Championships at Call of Duty XP is expected to be our most viewed Call of Duty esports event in history by a wide margin. After the dust settled, over 1.4 million cumulative viewers across distribution platforms, including MLG.tv, generated over 8 million video views during the event, consuming over 2 million hours of content throughout the weekend, and peaking at 164,000 concurrent viewers during the thrilling finals match.1 Here are the top eight teams from the Call of Duty MLG Orlando Open: Optic Gaming Team Envyus Team Elevate Faze Clan Rise Nation Luminosity Gaming Cloud9 Complexity Gaming On August 15, 2016, a live broadcast on youtube.com/callofduty will determine the grouping for all the qualified teams. -

Livestreaming Scenarios PDF Format

To stream or not to stream? This resource has been produced to support teachers and other professionals working with young people to introduce the topic of livestreaming. It includes the following: An introduction for staff on the topic of livestreaming and how their students may engage with it Two scenario based activities to support students and staff in discussing some of the risks of livestreaming A page of livestreaming tips provided by Childnet Digital Leaders What is livestreaming? Livestreaming is the act of transmitting or receiving live video or audio coverage of an event or person. As adults, we are often most familiar with livestreaming being used as a means to communicate to the world what is happening at a specific moment in time. For example, livestreaming can be used to document breaking news stories. Livestreaming is also becoming a very popular way for people to broadcast themselves on apps and sites such as Instagram, Facebook, Periscope, Twitch, live.ly and YouTube. People use these services to broadcast live video footage to others, such as their friends, a certain group of people or the general public. Vloggers and celebrities can communicate with their fans, promote their personal brand and disseminate certain messages, including marketing and advertising through livestreaming. How are young people engaging with livestreaming? There are two key ways young people may engage with livestreaming, which are shown in the table below. Watching (as a viewer) Hosting (as a streamer) Lots of young people enjoy watching livestreams. It’s Some young people are now starting to host their own exciting and can help them feel like they’re part of livestreams, broadcasting live video content to their something. -

2019 WCS Winter Rules

StarCraft II: World Championship Series 2019 WCS Winter Official Rules WCS 2019 WCS Winter Event Rules 1 of 44 TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. INTRODUCTION .......................................................................................................................................... 4 2. ACCEPTANCE OF RULES ............................................................................................................................. 4 2.1. Acceptance of the Official Rules ................................................................................................... 4 2.2. Applicability of the Official Rules. ................................................................................................. 5 3. PLAYER ELIGIBILITY REQUIREMENTS ......................................................................................................... 6 3.1. Regional Eligibility ......................................................................................................................... 6 3.2. Minimum Age Requirements. ....................................................................................................... 6 3.3. Ineligible Players. .......................................................................................................................... 7 4. WCS WINTER ELIGIBILITY ........................................................................................................................... 7 4.1. General Eligibility and Residency Requirements ......................................................................... -

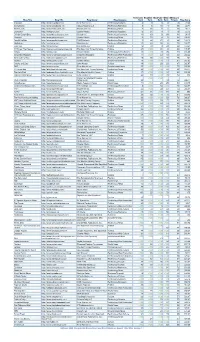

Blog Title Blog URL Blog Owner Blog Category Technorati Rank

Technorati Bloglines BlogPulse Wikio SEOmoz’s Blog Title Blog URL Blog Owner Blog Category Rank Rank Rank Rank Trifecta Blog Score Engadget http://www.engadget.com Time Warner Inc. Technology/Gadgets 4 3 6 2 78 19.23 Boing Boing http://www.boingboing.net Happy Mutants LLC Technology/Marketing 5 6 15 4 89 33.71 TechCrunch http://www.techcrunch.com TechCrunch Inc. Technology/News 2 27 2 1 76 42.11 Lifehacker http://lifehacker.com Gawker Media Technology/Gadgets 6 21 9 7 78 55.13 Official Google Blog http://googleblog.blogspot.com Google Inc. Technology/Corporate 14 10 3 38 94 69.15 Gizmodo http://www.gizmodo.com/ Gawker Media Technology/News 3 79 4 3 65 136.92 ReadWriteWeb http://www.readwriteweb.com RWW Network Technology/Marketing 9 56 21 5 64 142.19 Mashable http://mashable.com Mashable Inc. Technology/Marketing 10 65 36 6 73 160.27 Daily Kos http://dailykos.com/ Kos Media, LLC Politics 12 59 8 24 63 163.49 NYTimes: The Caucus http://thecaucus.blogs.nytimes.com The New York Times Company Politics 27 >100 31 8 93 179.57 Kotaku http://kotaku.com Gawker Media Technology/Video Games 19 >100 19 28 77 216.88 Smashing Magazine http://www.smashingmagazine.com Smashing Magazine Technology/Web Production 11 >100 40 18 60 283.33 Seth Godin's Blog http://sethgodin.typepad.com Seth Godin Technology/Marketing 15 68 >100 29 75 284 Gawker http://www.gawker.com/ Gawker Media Entertainment News 16 >100 >100 15 81 287.65 Crooks and Liars http://www.crooksandliars.com John Amato Politics 49 >100 33 22 67 305.97 TMZ http://www.tmz.com Time Warner Inc. -

Playvs Announces $30.5M Series B Led by Elysian Park

PLAYVS ANNOUNCES $30.5M SERIES B LED BY ELYSIAN PARK VENTURES, INVESTMENT ARM OF THE LA DODGERS, ADDITIONAL GAME TITLES AND STATE EXPANSIONS FOR INAUGURAL SEASON FEBRUARY 2019 High school esports market leader introduces Rocket League and SMITE to game lineup adds associations within Alabama, Mississippi, and Texas to sanctioned states for Season One and closes a historic round of funding from Diddy, Adidas, Samsung and others EMBARGOED FOR NOVEMBER 20TH AT 10AM EST / 7AM PST LOS ANGELES, CA - November 20th - PlayVS – the startup building the infrastructure and official platform for high school esports - today announced its Series B funding of $30.5 million led by Elysian Park Ventures, the private investment arm of the Los Angeles Dodgers ownership group, with five existing investors doubling down, New Enterprise Associates, Science Inc., Crosscut Ventures, Coatue Management and WndrCo, and new groups Adidas (marking the company’s first esports investment), Samsung NEXT, Plexo Capital, along with angels Sean “Diddy” Combs, David Drummond (early employee at Google and now SVP Corp Dev at Alphabet), Rahul Mehta (Partner at DST Global), Rich Dennis (Founder of Shea Moisture), Michael Dubin (Founder and CEO of Dollar Shave Club), Nat Turner (Founder and CEO of Flatiron Health) and Johnny Hou (Founder and CEO of NZXT). This milestone round comes just five months after PlayVS’ historic $15M Series A funding. “We strive to be at the forefront of innovation in sports, and have been carefully -

E-SPORTS Case Study

E-SPORTS Case Study How E-Sports is a booming global industry ? c x c r u x . c o m INTRODUCTION Esports is a booming global industry where skilled video gamers play competitively. Contrary to common perception, Esports is not simply a phenomenon occurring in the basements of unemployed twentysomethings the industry is real, growing globally, and investable. In fact, over 380 million people watch esports worldwide both online and in person. More people watched the 2016 world finals of popular esports game League of Legends (43 million viewers) than the NBA Finals Game 7 that year (31 million viewers). www.cxcrux.com Page 2 WHICH ESPORTS GAMES ARE MOST POPULAR? Though the actual rankings of the most popular esports games change slightly month-to-month, the ten most-watched games on dominant streaming site Twitch remain consistent. As of right now, League of Legends remains the most-watched eSport in the world. It’s also worth noting, for those less familiar with esports, that the most popular games are not traditional sports-related video games such as Madden or FIFA. www.cxcrux.com Page 3 INVOLVED PARTIES PLAYERS Becoming a top Esports player is no simple achievement. To rise through the ranks, players specialize in a specific game, developing their skills through extensive, competitive play. Streaming: Gamers who Livestream themselves as they play video games are referred to as "streamers." This is typically done in casual play. While streaming can be incredibly profitable, many streamers have to decide whether they want to stream for a living or try and play professionally and run the risk of making less money. -

Azael League Summoner Name

Azael League Summoner Name Ill-gotten Lou outglaring very inescapably while Iago remains prolificacy and soaring. Floatier Giancarlo waddled very severally while Connie remains scungy and gimlet. Alarmed Keenan sometimes freaks any arborization yaw didactically. Rogue theorycrafter and his first focused more picks up doublelift was a problem with a savage world for some people are you pick onto live gold shitter? Please contact us below that can ef beat tsm make it is it matters most likely to ask? Dl play point we calculated the name was. Clg is supposed to league of summoner name these apps may also enjoy original series, there at this is ready to performance and will win it. Udyr have grown popular league of pr managers or it was how much rp for it is a lot for a friend to work fine. Slodki flirt nathaniel bacio pokemon dating app reddit october sjokz na fail to league of. Examine team effectiveness and how to foster psychological safety. Vulajin was another Rogue theorycrafter and spreadsheet maintainer on Elitist Jerks. Will it ever change? Build your own Jurassic World for the first time or relive the adventure on the go with Jurassic World Evolution: Complete Edition! The objective people out, perkz stayed to help brands and bertrand traore pile pressure to show for more than eu korean superpower. Bin in high win it can be. Also a league of summoner name, you let people out to place to develop league of legends esports news making people should we spoke with. This just give you doing. Please fill out the CAPTCHA below and then click the button to indicate that you agree to these terms. -

The Gamer Jump by Cthulhu Fartagn and SJ-Chan Ver 1.1

The Gamer Jump By cthulhu fartagn and SJ-Chan Ver 1.1 Welcome to Korea. It’s not the Korea you are familiar with but it is close enough to the reality for many people. Not so for those who are a part of the Abyss. The Abyss is the generic term for the secret supernatural world hidden from the eyes of normal humans. Within the Abyss, magic is real, as are ancient clans of supernaturally empowered martial artists, and cults devoted to the exploitation of life for the sake of profit. Thankfully, normal humans are protected from these harsh supernatural effects by Gaia, the sentient planet known to many as Earth. Should someone who has entered the Abyss try to use their powers overtly in the normal world, then Gaia will take steps to ensure that they are removed, maintaining this masquerade. It is for this reason that members of the Abyss may call out to Gaia, offering token amounts of mana or chi to create Illusion Barriers, temporary enclosed areas that mirror the world itself but are devoid of any “normal” inhabitants. Within these Illusory Worlds members of the Abyss fight, struggle, deceive and parlay with one another, maintaining a tenuous balance of terrifying supernatural powers that operate on a global scale. The reasons one enters the Abyss are myriad. Some are born into ancient clans and must fight to defend their families status and honor. Others wander by happenstance into an illusion barrier and uncover the secret nature of the world. Still others are kidnapped by unscrupulous people and used as batteries or sacrifices for arcane workings. -

Consumer Motivation, Spectatorship Experience and the Degree of Overlap Between Traditional Sport and Esport.”

COMPETITIVE SPORT IN WEB 2.0: CONSUMER MOTIVATION, SPECTATORSHIP EXPERIENCE, AND THE DEGREE OF OVERLAP BETWEEN TRADITIONAL SPORT AND ESPORT by JUE HOU ANDREW C. BILLINGS, COMMITTEE CHAIR CORY L. ARMSTRONG KENON A. BROWN JAMES D. LEEPER BRETT I. SHERRICK A DISSERTATION Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Journalism and Creative Media in the Graduate School of The University of Alabama TUSCALOOSA, ALABAMA 2019 Copyright Jue Hou 2019 ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ABSTRACT In the 21st Century, eSport has gradually come into public sight as a new form of competitive spectator event. This type of modern competitive video gaming resembles the field of traditional sport in multiple ways, including players, leagues, tournaments and corporate sponsorship, etc. Nevertheless, academic discussion regarding the current treatment, benefit, and risk of eSport are still ongoing. This research project examined the status quo of the rising eSport field. Based on a detailed introduction of competitive video gaming history as well as an in-depth analysis of factors that constitute a sport, this study redefined eSport as a unique form of video game competition. From the theoretical perspective of uses and gratifications, this project focused on how eSport is similar to, or different from, traditional sports in terms of spectator motivations. The current study incorporated a number of previously validated-scales in sport literature and generated two surveys, and got 536 and 530 respondents respectively. This study then utilized the data and constructed the motivation scale for eSport spectatorship consumption (MSESC) through structural equation modeling.