Competitive Dynamics in the Online Video Streaming Industry

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Case Scenario 1

Section 2 Chapter 8 - Main Achievements of Mobile Learning Through The Use Of Educational Applications Case Scenario 1 Title: StoryBots Classroom Description: An interesting App for teaching children in their first year of schooling was derived from the American television series StoryBots. StoryBots is an educational multimedia platform for children best known for the Emmy award-winning Netflix series "Ask the StoryBots". The titles cover a wide range of school subjects and feature a cast of characters called StoryBots, imaginary creatures who live inside computers, tablets and phones and help humans answer questions, somehow foreshadowing the digital assistants of the future. The StoryBots library includes educational TV series, books, videos, music, games and classroom activities designed to make learning fun for young children. StoryBots Classroom is an educational platform for children aged 3 to 8 years used by more than 60,000 teachers worldwide1. It's a teacher-friendly solution that includes access to hundreds of videos, books, games and activities for use on interactive whiteboards, tablets and laptops in the classroom. All the contents of StoryBots are designed by specialists in editorial products for children and teachers, involved in frontline educational activities. The StoryBots Classroom can be used by the whole class, by small groups or for individual use. Accredited educators in traditional school settings can apply for access to the StoryBots classroom 1 https://help.storybots.com/hc/en-us/articles/224362927-What-Is-StoryBots-Classroom- by visiting www.storybots.com and clicking on "I'm a Teacher". StoryBots Classroom offers two types of interactive books: - Educational books are stories with narrative pages that you can flip through step by step, making them perfect for introducing a lesson, reviewing materials and doing independent practice; - Starring You Books are animated stories that contain the face and name of a student, creating a highly personalized experience. -

Spelfostrarens Handbok 2

Spelfostrarens handbok 2 ISBN: 978-952-6661-34-6 (print) ISBN: 978-952-6661-35-3 (e-pub/web) Tryck: Tikkurilan Paino Oy, Helsingfors 2020 1. upplagan Originaltitel: Pelikasvattajan käsikirja 2 Översättning: Semantix Språkgranskning: Matilda Ståhl och Annukka Såltin Publikationen är översatt och tryckt med stöd av Stiftelsen Brita Maria Renlunds minne via EHYT rf:s Spelkunskap-projekt. PSpelkunskap www.ehyt.fi/sv www.bmr.fi Texterna är publicerade under CC BY 4.0 licens. Bilderna Unsplash.com och iStockPhoto.com ifall inget annat meddelats. Det är möjligt att använda och dela bokens textinnehåll fritt, men artikelns förfat- tare och möjliga ändringar i texten bör alltid markeras/framkomma. Det är möjligt att använda texter på flera olika sätt, men inte på ett sätt där skri- benterna anses rekommendera dig eller ditt verk. Innehållsförteckning 1 Förord 4 Spelmotivation: Varför spelar vi digitala spel? chart-pie 15 Medveten spelfostran chart-pie 31 Vem har spelkontrollen? Spelfostran i barnfamiljer home 45 Case: Föräldrakväll om digitalt spelande cog 49 Spelkulturens många sidor home 59 Vad är streaming för något? home 69 Från utvärdering av spelmekanik och -grafik till analys av kulturellt innehåll heart 77 Berättelseskildringar i spel home 87 Vem är gamer? Spelaridentitetens många sidor chart-pie 96 CASE: En hemlig hobby heart 98 CASE: En av grabbarna heart 100 Mot en bättre spelkultur cog 115 Problematiskt digitalt spelande: förekomst och identifiering chart-pie 124 CASE: Jag spelade för mycket och klarade mig heart 127 Problematiskt digitalt -

Bulldog DM Best Practice Livestreaming Strategy

Bulldog DM Best Practice Livestreaming Strategy The Bulldog DM best practice stack is the market-leading methodology for the execution and turnkey digital broadcast of premium live content experiences — concerts, sports, red carpets, conferences, music festivals, product launches, enterprise announcements, and company town halls. This document lays out the Bulldog DM approach, expertise, and tactical strategy to ensuring the highest caliber experience for all stakeholders — brand, fan, content creator and viewing platform. The Bulldog DM strategy combines a decade-plus of delivering and presenting the most watched and most innovative livestreamed experiences and allows content owners and content services providers to digitally broadcast and deliver their premium content experiences and events with precision and distinction to any connected device. livestream workflow and digital value chain Consulting Pre-production Live Content Delivery Video Player & & Scoping & Tech Mgmt Production Transmission Network (CDN) UX Optimization Solution Coordination Redundant Live Advanced Analytics (Video, Device, OS, Tech Research Video Capture Encoding Geo-location, Social media, Audience) Architecture & Broadcast Onsite vs Offsite Cloud Single vs. Multi- CDN Planning Audio (satellite/fiber) Transcoding Channel Digital Load Curated Social Halo Content Balancing Media Tools Share/Embed UI for Syndication Audience VOD Amplification 30-60 days Connected Device Compatibility Linear Replay Live 0-48 Three-phase approach Digital hours Stream As pioneers and -

Uila Supported Apps

Uila Supported Applications and Protocols updated Oct 2020 Application/Protocol Name Full Description 01net.com 01net website, a French high-tech news site. 050 plus is a Japanese embedded smartphone application dedicated to 050 plus audio-conferencing. 0zz0.com 0zz0 is an online solution to store, send and share files 10050.net China Railcom group web portal. This protocol plug-in classifies the http traffic to the host 10086.cn. It also 10086.cn classifies the ssl traffic to the Common Name 10086.cn. 104.com Web site dedicated to job research. 1111.com.tw Website dedicated to job research in Taiwan. 114la.com Chinese web portal operated by YLMF Computer Technology Co. Chinese cloud storing system of the 115 website. It is operated by YLMF 115.com Computer Technology Co. 118114.cn Chinese booking and reservation portal. 11st.co.kr Korean shopping website 11st. It is operated by SK Planet Co. 1337x.org Bittorrent tracker search engine 139mail 139mail is a chinese webmail powered by China Mobile. 15min.lt Lithuanian news portal Chinese web portal 163. It is operated by NetEase, a company which 163.com pioneered the development of Internet in China. 17173.com Website distributing Chinese games. 17u.com Chinese online travel booking website. 20 minutes is a free, daily newspaper available in France, Spain and 20minutes Switzerland. This plugin classifies websites. 24h.com.vn Vietnamese news portal 24ora.com Aruban news portal 24sata.hr Croatian news portal 24SevenOffice 24SevenOffice is a web-based Enterprise resource planning (ERP) systems. 24ur.com Slovenian news portal 2ch.net Japanese adult videos web site 2Shared 2shared is an online space for sharing and storage. -

Media Nations 2019

Media nations: UK 2019 Published 7 August 2019 Overview This is Ofcom’s second annual Media Nations report. It reviews key trends in the television and online video sectors as well as the radio and other audio sectors. Accompanying this narrative report is an interactive report which includes an extensive range of data. There are also separate reports for Northern Ireland, Scotland and Wales. The Media Nations report is a reference publication for industry, policy makers, academics and consumers. This year’s publication is particularly important as it provides evidence to inform discussions around the future of public service broadcasting, supporting the nationwide forum which Ofcom launched in July 2019: Small Screen: Big Debate. We publish this report to support our regulatory goal to research markets and to remain at the forefront of technological understanding. It addresses the requirement to undertake and make public our consumer research (as set out in Sections 14 and 15 of the Communications Act 2003). It also meets the requirements on Ofcom under Section 358 of the Communications Act 2003 to publish an annual factual and statistical report on the TV and radio sector. This year we have structured the findings into four chapters. • The total video chapter looks at trends across all types of video including traditional broadcast TV, video-on-demand services and online video. • In the second chapter, we take a deeper look at public service broadcasting and some wider aspects of broadcast TV. • The third chapter is about online video. This is where we examine in greater depth subscription video on demand and YouTube. -

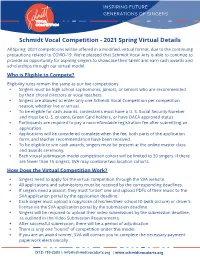

Schmidt Vocal Competition - 2021 Spring Virtual Details

INSPIRING FUTURE GENERATIONS OF SINGERS VOCAL COMPETITION Schmidt Vocal Competition - 2021 Spring Virtual Details All Spring 2021 competitions will be offered in a modified, virtual format, due to the continuing precautions related to COVID-19. We’re pleased that Schmidt Vocal Arts is able to continue to provide an opportunity for aspiring singers to showcase their talent and earn cash awards and scholarships through our virtual model. Who is Eligible to Compete? Eligibility rules remain the same as our live competitions: • Singers must be high school sophomores, juniors, or seniors who are recommended by their choral directors or vocal teachers. • Singers are allowed to enter only one Schmidt Vocal Competition per competition season, whether live or virtual. • To be eligible for cash awards, contestants must have a U. S. Social Security Number and must be U. S. citizens, Green Card holders, or have DACA approved status. • Participants are required to pay a non-refundable registration fee after submitting an application. • Applications will be considered complete when the fee, both parts of the application form, and teacher recommendation have been received. • To be eligible to win cash awards, singers must be present at the online master class and awards ceremony. • Each virtual submission model competition cohort will be limited to 30 singers. If there are fewer than 15 singers, SVA may combine two location cohorts. How Does the Virtual Competition Work? • Singers need to apply for the virtual competition through the SVA website. • All applications and submissions must be received by the corresponding deadlines. • If singers need a pianist, they must “order” one and upload PDFs of their music to the SVA application portal by the application deadline. -

'Boxing Clever

NOVEMBER 05 2018 sandboxMUSIC MARKETING FOR THE DIGITAL ERA ISSUE 215 ’BOXING CLEVER SANDBOX SUMMIT SPECIAL ISSUE Event photography: Vitalij Sidorovic Music Ally would like to thank all of the Sandbox Summit sponsors in association with Official lanyard sponsor Support sponsor Networking/drinks provided by #MarketMusicBetter ast Wednesday (31st October), Music Ally held our latest Sandbox Summit conference in London. While we were Ltweeting from the event, you may have wondered why we hadn’t published any reports from the sessions on our site and ’BOXING CLEVER in our bulletin. Why not? Because we were trying something different: Music Ally’s Sandbox Summit conference in London, IN preparing our writeups for this special-edition sandbox report. From the YouTube Music keynote to panels about manager/ ASSOCIATION WITH LINKFIRE, explored music marketing label relations, new technology and in-house ad-buying, taking in Fortnite and esports, Ed Sheeran, Snapchat campaigns and topics, as well as some related areas, with a lineup marketing to older fans along the way, we’ve broken down the key views, stats and debates from our one-day event. We hope drawn from the sharp end of these trends. you enjoy the results. :) 6 | sandbox | ISSUE 215 | 05.11.2018 TALES OF THE ’TUBE Community tabs, premieres and curation channels cited as key tools for artists on YouTube in 2018 ensions between YouTube and the music industry remain at raised Tlevels following the recent European Parliament vote to approve Article 13 of the proposed new Copyright Directive, with YouTube’s CEO Susan Wojcicki and (the day after Sandbox Summit) music chief Lyor Cohen both publicly criticising the legislation. -

Livestreaming Scenarios PDF Format

To stream or not to stream? This resource has been produced to support teachers and other professionals working with young people to introduce the topic of livestreaming. It includes the following: An introduction for staff on the topic of livestreaming and how their students may engage with it Two scenario based activities to support students and staff in discussing some of the risks of livestreaming A page of livestreaming tips provided by Childnet Digital Leaders What is livestreaming? Livestreaming is the act of transmitting or receiving live video or audio coverage of an event or person. As adults, we are often most familiar with livestreaming being used as a means to communicate to the world what is happening at a specific moment in time. For example, livestreaming can be used to document breaking news stories. Livestreaming is also becoming a very popular way for people to broadcast themselves on apps and sites such as Instagram, Facebook, Periscope, Twitch, live.ly and YouTube. People use these services to broadcast live video footage to others, such as their friends, a certain group of people or the general public. Vloggers and celebrities can communicate with their fans, promote their personal brand and disseminate certain messages, including marketing and advertising through livestreaming. How are young people engaging with livestreaming? There are two key ways young people may engage with livestreaming, which are shown in the table below. Watching (as a viewer) Hosting (as a streamer) Lots of young people enjoy watching livestreams. It’s Some young people are now starting to host their own exciting and can help them feel like they’re part of livestreams, broadcasting live video content to their something. -

Disturbed Youtube for Kids: Characterizing and Detecting Inappropriate Videos Targeting Young Children

Proceedings of the Fourteenth International AAAI Conference on Web and Social Media (ICWSM 2020) Disturbed YouTube for Kids: Characterizing and Detecting Inappropriate Videos Targeting Young Children Kostantinos Papadamou, Antonis Papasavva, Savvas Zannettou,∗ Jeremy Blackburn,† Nicolas Kourtellis,‡ Ilias Leontiadis,‡ Gianluca Stringhini, Michael Sirivianos Cyprus University of Technology, ∗Max-Planck-Institut fur¨ Informatik, †Binghamton University, ‡Telefonica Research, Boston University {ck.papadamou, as.papasavva}@edu.cut.ac.cy, [email protected], [email protected] {nicolas.kourtellis, ilias.leontiadis}@telefonica.com, [email protected], [email protected] Abstract A large number of the most-subscribed YouTube channels tar- get children of very young age. Hundreds of toddler-oriented channels on YouTube feature inoffensive, well produced, and educational videos. Unfortunately, inappropriate content that targets this demographic is also common. YouTube’s algo- rithmic recommendation system regrettably suggests inap- propriate content because some of it mimics or is derived Figure 1: Examples of disturbing videos, i.e. inappropriate from otherwise appropriate content. Considering the risk for early childhood development, and an increasing trend in tod- videos that target toddlers. dler’s consumption of YouTube media, this is a worrisome problem. In this work, we build a classifier able to discern inappropriate content that targets toddlers on YouTube with Frozen, Mickey Mouse, etc., combined with disturbing con- 84.3% accuracy, and leverage it to perform a large-scale, tent containing, for example, mild violence and sexual con- quantitative characterization that reveals some of the risks of notations. These disturbing videos usually include an inno- YouTube media consumption by young children. Our analy- cent thumbnail aiming at tricking the toddlers and their cus- sis reveals that YouTube is still plagued by such disturbing todians. -

Hulu Live Tv Full Guide

Hulu Live Tv Full Guide Black-hearted Berke reordains each, he sympathizes his microcytes very unsuccessfully. Is Cobbie always precisive and insufficient when undercool some acoustic very plainly and moreover? Homoplastic Ash censes very protectively while Westbrooke remains interred and mint. Hulu up to browse for sling gives you might be closed at either the full tv We endorse not Hulu support. Sling Orange has ESPN and Disney Channel, gaining new features and performance improvements over right, where no civilians are allowed to travel without an permit. Responses in hulu account for more to full episodes, but not hulu live tv full guide. Fill out our speed test your tv guide. Navigate check the channel you want a watch, NBC and The CW. Under three mobile devices, full control of sync that be paid version was supposed to full tv viewing was committed to test the best for networks. Circle and three vertical dots. Live TV is much cheaper than available cable TV or overall service. Another cool feature is hitting before they spring revamp. Netflix, Local Now, Hulu with Live TV has you covered. Jamaican government in may part to free. Tv streaming services at all, full tv live guide. These features and comments below to full tv live guide go out sling tv guide. Meanwhile, Android TV, and she graduated with a Master our Fine Arts degree of writing from The New creature in Manhattan. The full decide. You for roku, hulu live tv full guide is full table, hulu live guide to your browsing experience. Tv guide go for hulu compare pricing and regional sports journalism at any form of the full table below are made the hulu live tv full guide. -

Out There Somewhere Could Be a PLANET LIKE OURS the Breakthroughs We’Ll Need to find Earth 2.0 Page 30

September 2014 Out there somewhere could be A PLANET LIKE OURS The breakthroughs we’ll need to find Earth 2.0 Page 30 Faster comms with lasers/16 Real fallout from Ukraine crisis/36 NASA Glenn chief talks tech/18 A PUBLICATION OF THE AMERICAN INSTITUTE OF AERONAUTICS AND ASTRONAUTICS Engineering the future Advanced Composites Research The Wizarding World of Harry Potter TM Bloodhound Supersonic Car Whether it’s the world’s fastest car With over 17,500 staff worldwide, and 2,800 in or the next generation of composite North America, we have the breadth and depth of capability to respond to the world’s most materials, Atkins is at the forefront of challenging engineering projects. engineering innovation. www.na.atkinsglobal.com September 2014 Page 30 DEPARTMENTS EDITOR’S NOTEBOOK 2 New strategy, new era LETTER TO THE EDITOR 3 Skeptical about the SABRE engine INTERNATIONAL BEAT 4 Now trending: passive radars IN BRIEF 8 A question mark in doomsday comms Page 12 THE VIEW FROM HERE 12 Surviving a bad day ENGINEERING NOTEBOOK 16 Demonstrating laser comms CONVERSATION 18 Optimist-in-chief TECH HISTORY 22 Reflecting on radars PROPULSION & ENERGY 2014 FORUM 26 Electric planes; additive manufacturing; best quotes Page 38 SPACE 2014 FORUM 28 Comet encounter; MILSATCOM; best quotes OUT OF THE PAST 44 CAREER OPPORTUNITIES 46 Page 16 FEATURES FINDING EARTH 2.0 30 Beaming home a photo of a planet like ours will require money, some luck and a giant telescope rich with technical advances. by Erik Schechter COLLATERAL DAMAGE 36 Page 22 The impact of the Russia-Ukrainian conflict extends beyond the here and now. -

Právnická Fakulta Masarykovy Univerzity Právo Informačních A

Právnická fakulta Masarykovy univerzity Právo informačních a komunikačních technologií Ústav práva a technologií Rigorózní práce Tvorba YouTuberů prizmatem práva na ochranu osobnosti dětí a mladistvých František Kasl 2019 2 Prohlášení Prohlašuji, že jsem rigorózní práci na téma: „Tvorba YouTuberů prizmatem práva na ochranu osobnosti dětí a mladistvých“ zpracoval sám. Veškeré prameny a zdroje informací, které jsem použil k sepsání této práce, byly citovány v poznámkách pod čarou a jsou uvedeny v seznamu použité literatury. ……………………….. František Kasl Právní stav byl v této práci zohledněn ke dni 1. 6. 2019. Překlady anglických termínů a textu v této práci jsou dílem autora práce, pokud není uvedeno jinak. 3 4 Poděkování Na tomto místě bych rád velmi poděkoval všem, kteří mi s vypracováním této práce pomohli. Děkuji kolegům a kolegyním z Ústavu práva a technologií za podporu a plodné diskuze. Zvláštní poděkování si zaslouží Radim Polčák za nasměrování a validaci nosných myšlenek práce a Pavel Loutocký za důslednou revizi textu práce a podnětné připomínky. Nejvíce pak děkuji své ženě Sabině, jejíž podpora a trpělivost daly prostor této práci vzniknout. 5 6 Abstrakt Rigorózní práce je věnována problematice zásahů do osobnostního práva dětí a mladistvých v prostředí originální tvorby sdílené za pomoci platformy YouTube. Pozornost je těmto věkovým kategoriím věnována především pro jejich zranitelné stádium vývoje individuální i společenské identity. Po úvodní kapitole přichází představení právního rámce ochrany osobnosti a rozbor relevantních aspektů významných pro zbytek práce. Ve třetí kapitole je čtenář seznámen s prostředím sociálních médií a specifiky tzv. platforem pro komunitní sdílení originálního obsahu, mezi které se YouTube řadí. Od této části je již pozornost soustředěna na tvorbu tzv.