QIU, Yuanbo 420026435 Thesis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Uila Supported Apps

Uila Supported Applications and Protocols updated Oct 2020 Application/Protocol Name Full Description 01net.com 01net website, a French high-tech news site. 050 plus is a Japanese embedded smartphone application dedicated to 050 plus audio-conferencing. 0zz0.com 0zz0 is an online solution to store, send and share files 10050.net China Railcom group web portal. This protocol plug-in classifies the http traffic to the host 10086.cn. It also 10086.cn classifies the ssl traffic to the Common Name 10086.cn. 104.com Web site dedicated to job research. 1111.com.tw Website dedicated to job research in Taiwan. 114la.com Chinese web portal operated by YLMF Computer Technology Co. Chinese cloud storing system of the 115 website. It is operated by YLMF 115.com Computer Technology Co. 118114.cn Chinese booking and reservation portal. 11st.co.kr Korean shopping website 11st. It is operated by SK Planet Co. 1337x.org Bittorrent tracker search engine 139mail 139mail is a chinese webmail powered by China Mobile. 15min.lt Lithuanian news portal Chinese web portal 163. It is operated by NetEase, a company which 163.com pioneered the development of Internet in China. 17173.com Website distributing Chinese games. 17u.com Chinese online travel booking website. 20 minutes is a free, daily newspaper available in France, Spain and 20minutes Switzerland. This plugin classifies websites. 24h.com.vn Vietnamese news portal 24ora.com Aruban news portal 24sata.hr Croatian news portal 24SevenOffice 24SevenOffice is a web-based Enterprise resource planning (ERP) systems. 24ur.com Slovenian news portal 2ch.net Japanese adult videos web site 2Shared 2shared is an online space for sharing and storage. -

List of Brands

Global Consumer 2019 List of Brands Table of Contents 1. Digital music 2 2. Video-on-Demand 4 3. Video game stores 7 4. Digital video games shops 11 5. Video game streaming services 13 6. Book stores 15 7. eBook shops 19 8. Daily newspapers 22 9. Online newspapers 26 10. Magazines & weekly newspapers 30 11. Online magazines 34 12. Smartphones 38 13. Mobile carriers 39 14. Internet providers 42 15. Cable & satellite TV provider 46 16. Refrigerators 49 17. Washing machines 51 18. TVs 53 19. Speakers 55 20. Headphones 57 21. Laptops 59 22. Tablets 61 23. Desktop PC 63 24. Smart home 65 25. Smart speaker 67 26. Wearables 68 27. Fitness and health apps 70 28. Messenger services 73 29. Social networks 75 30. eCommerce 77 31. Search Engines 81 32. Online hotels & accommodation 82 33. Online flight portals 85 34. Airlines 88 35. Online package holiday portals 91 36. Online car rental provider 94 37. Online car sharing 96 38. Online ride sharing 98 39. Grocery stores 100 40. Banks 104 41. Online payment 108 42. Mobile payment 111 43. Liability insurance 114 44. Online dating services 117 45. Online event ticket provider 119 46. Food & restaurant delivery 122 47. Grocery delivery 125 48. Car Makes 129 Statista GmbH Johannes-Brahms-Platz 1 20355 Hamburg Tel. +49 40 2848 41 0 Fax +49 40 2848 41 999 [email protected] www.statista.com Steuernummer: 48/760/00518 Amtsgericht Köln: HRB 87129 Geschäftsführung: Dr. Friedrich Schwandt, Tim Kröger Commerzbank AG IBAN: DE60 2004 0000 0631 5915 00 BIC: COBADEFFXXX Umsatzsteuer-ID: DE 258551386 1. -

Houston, Hong Kong, and Seoul Best Cities for Twitch

Study: Houston, Hong Kong, and Seoul best cities for Twitch streamers Internet speeds, hardware prices, gaming expos and the cost of living make these cities a Twitch streamer’s paradise LONDON - June 29th 2021 - Broadband Savvy, a leading authority in broadband service and performance, today released the results of a months-long study on the best and worst cities in the world for live streamers. The research found that Houston, Texas; Hong Kong, and Seoul, South Korea were the top three best cities for live streamers on websites such as Twitch.tv to live. The study examined cities based on broadband costs and connectivity, 5G coverage, the cost of PC components, the cost of camera gear, the frequency of gaming/streaming expos, and the cost of rent. The complete dataset is available for download here. Houston achieved first place because it offers an excellent overall package for streamers on platforms such as Twitch and YouTube. The city enjoys fast download and upload speeds, low hardware costs, and a low cost of rent compared to other developed cities. “If you stream on Twitch, Houston is a fantastic place to live,” said Tom Paton, founder of Broadband Savvy. “It’s easy to find high-speed internet for a fairly low cost, and the city has great 5G coverage, which is perfect for real-life streamers. There’s a good selection of local gaming expos, but Houston is also a short flight to the west coast, where TwitchCon is typically held each year.” Other cities in the United States also featured in the top ten, but were often let down by their cost of living. -

Page 1 of 375 6/16/2021 File:///C:/Users/Rtroche

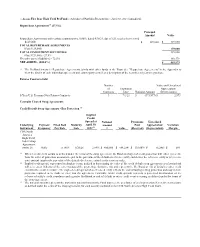

Page 1 of 375 :: Access Flex Bear High Yield ProFund :: Schedule of Portfolio Investments :: April 30, 2021 (unaudited) Repurchase Agreements(a) (27.5%) Principal Amount Value Repurchase Agreements with various counterparties, 0.00%, dated 4/30/21, due 5/3/21, total to be received $129,000. $ 129,000 $ 129,000 TOTAL REPURCHASE AGREEMENTS (Cost $129,000) 129,000 TOTAL INVESTMENT SECURITIES 129,000 (Cost $129,000) - 27.5% Net other assets (liabilities) - 72.5% 340,579 NET ASSETS - (100.0%) $ 469,579 (a) The ProFund invests in Repurchase Agreements jointly with other funds in the Trust. See "Repurchase Agreements" in the Appendix to view the details of each individual agreement and counterparty as well as a description of the securities subject to repurchase. Futures Contracts Sold Number Value and Unrealized of Expiration Appreciation/ Contracts Date Notional Amount (Depreciation) 5-Year U.S. Treasury Note Futures Contracts 3 7/1/21 $ (371,977) $ 2,973 Centrally Cleared Swap Agreements Credit Default Swap Agreements - Buy Protection (1) Implied Credit Spread at Notional Premiums Unrealized Underlying Payment Fixed Deal Maturity April 30, Amount Paid Appreciation/ Variation Instrument Frequency Pay Rate Date 2021(2) (3) Value (Received) (Depreciation) Margin CDX North America High Yield Index Swap Agreement; Series 36 Daily 5 .00% 6/20/26 2.89% $ 450,000 $ (44,254) $ (38,009) $ (6,245) $ 689 (1) When a credit event occurs as defined under the terms of the swap agreement, the Fund as a buyer of credit protection will either (i) receive from the seller of protection an amount equal to the par value of the defaulted reference entity and deliver the reference entity or (ii) receive a net amount equal to the par value of the defaulted reference entity less its recovery value. -

Patterns of Communication in Live Streaming——A Comparison of China and the United States

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Göteborgs universitets publikationer - e-publicering och e-arkiv Patterns of Communication in Live Streaming A comparison of China and the United States SHUQIAN. ZHOU MEIMEI. WANG Master of Communication Thesis Report nr. 2017:088 University of Gothenburg Department of Applied Information Technology Gothenburg, Sweden, May 2017 Patterns of communication in live streaming——A comparison of China and the United States Acknowledgements First of all, we would like to express our sincere gratitude to our supervisor, Prof. Jens Allwood, for his weekly meetings during this half year and the constructive suggestions to our thesis. We learned a lot from him, not only his profound knowledge in communication, but also his rigorous academic attitude. We appreciate all of his efforts in our thesis. We would also like to thank our teachers of Master in Communication. They helped us build our knowledge systems in communication from the very beginning and keep enriching the systems within the two years. They also encouraged us to cooperate with each other and present ourselves a lot. We are grateful for their help in our study. Our sincere thanks also goes to our classmates, for their help and support for us in the whole two years. Finally, we must express our gratitude to our parents for providing us with unfailing support and continuous encouragement throughout our two years of study. This thesis would not have been possible without them. Thank you all again. Patterns of communication in live streaming——A comparison of China and the United States Abstract Live streaming as a social medium provides a multi-functional internet platform for its users to have real-time interaction with others through broadcasting live streaming videos by mobile devices and websites. -

Streamwiki: Enabling Viewers of Knowledge Sharing Live Streams to Collaboratively Generate Archival Documentation for Effective In-Stream and Post-Hoc Learning

StreamWiki: Enabling Viewers of Knowledge Sharing Live Streams to Collaboratively Generate Archival Documentation for Effective In-Stream and Post-Hoc Learning ZHICONG LU, Computer Science, University of Toronto, Canada SEONGKOOK HEO, Computer Science, University of Toronto, Canada DANIEL WIGDOR, Computer Science, University of Toronto, Canada Knowledge-sharing live streams are distinct from traditional educational videos, in part due to the large concurrently-viewing audience and the real-time discussions that are possible between viewers and the streamer. Though this medium creates unique opportunities for interactive learning, it also brings about the challenge of creating a useful archive for post-hoc learning. This paper presents the results of interviews with knowledge sharing streamers, their moderators, and viewers to understand current experiences and needs for sharing and learning knowledge through live streaming. Based on those findings, we built StreamWiki, a tool which leverages the availability of live stream viewers to produce useful archives of the interactive learning experience. On StreamWiki, moderators initiate high-level tasks that viewers complete by conducting microtasks, such as writing summaries, sending comments, and voting for informative comments. As a result, a summary document is built in real time. Through the tests of our prototype with streamers and viewers, we found that StreamWiki could help viewers understand the content and the context of the stream, during the stream and also later, for post-hoc learning. CSS Concepts: • Human-centered computing → Collaborative and social computing → Collaborative and social computing systems and tools KEYWORDS Live streaming; knowledge sharing; knowledge building; collaborative documentation; learning ACM Reference format: Zhicong Lu, Seongkook Heo, and Daniel Wigdor. -

February 2021 Disclaimer

FEBRUARY 2021 DISCLAIMER Investors should consider the investment objectives, risk, charges and expenses carefully before investing. For a prospectus or summary prospectus with this and other information about Roundhill ETFs please call 1-877-220-7649 or visit the website at https://www.roundhillinvestments.com/etf. Read the prospectus or summary prospectus carefully before investing. Investing involves risk, including possible loss of principal. Esports gaming companies face intense competition, both domestically and internationally, may have products that face rapid obsolescence, and are heavily dependent on the protection of patent and intellectual property rights. Such factors may adversely affect the profitability and value of video gaming companies. Investments made in small and mid-capitalization companies may be more volatile and less liquid due to limited resources or product lines and more sensitive to economic factors. Fund investments will be concentrated in an industry or group of industries, and the value of Fund shares may risk and fall more than diversified funds. Foreign investing involves social and political instability, market illiquidity, exchange- rate fluctuation, high volatility and limited regulation risks. Emerging markets involve different and greater risks, as they are smaller, less liquid and more volatile than more developed countries. Depository Receipts involve risks similar to those associated investments in foreign securities, but may not provide a return that corresponds precisely with that of the underlying shares. Please see the prospectus for details of these and other risks. Roundhill Financial Inc. serves as the investment advisor. The Funds are distributed by Foreside Fund Services, LLC which is not affiliated with Roundhill Financial Inc., U.S. -

Biggest Moneymaker’ in the $150 Billion Gaming

Gaming is booming in China as the coronavirus means more time at home With the coronavirus still raging on in China and70,548 confirmed cases, and 1,770 deaths it is no wonder that much of China remains in lockdown. As a result, online gaming activity is setting record highs in China as more people spend more time at home. The implication for investors is that Chinese gaming-related companies should be in for a booming quarter when they next report results. While some of this is already priced into gaming stocks, should the coronavirus last longer more gains can be expected. Tencent rallies 10% in the past month as more Chinese stay at home gaming Last month when I wrote: “The Wuhan Coronavirus crisis leads to some investment opportunities” I mentioned that Chinese internet stocks can be possible winners including gaming and social media giant Tencent (OTC: TCEHY). The stock has rallied 10% since then. The longer the coronavirus has a significant impact then I expect the Tencent rally to continue. Game live streaming hours watched up 17% in January VentureBeat just reported that game live streaming was up 17% to nearly 500 million view hours in January 2020. The most popular streaming sites were Amazon’s Twitch (NASDAQ: AMZN), Alphabet Google’s (NASDAQ: GOOGL) (NASDAQ: GOOG) YouTube Gaming, Facebook Gaming (NASDAQ: FB), and Microsoft (NASDAQ: MSFT) Mixer. In China, Tencent backed Douyu and Huya will benefit from increased live streaming. Ironically Douyu’s headquarters is located in Wuhan, the center of the coronavirus epidemic. A game called ‘Plague Inc.’ has become highly popular and is like the real-life coronavirus threat Ironically one of the most popular games in China nowadays is titled “Plague Inc’. -

Investor Deck

ROUNDHILL INVESTMENTS NERD The Esports & Digital Entertainment ETF INVESTOR PRESENTATION JUNE 2021 ROUNDHILL INVESTMENTS Disclaimer Investors should consider the investment objectives, risk, charges and expenses carefully before investing. For a prospectus or summary prospectus with this and other information about the NERD ETF please call 1-877-220-7649 or visit the website at roundhillinvestments.com/etf/nerd. Read the prospectus or summary prospectus carefully before investing. Investing involves risk, including possible loss of principal. Esports gaming companies face intense competition, both domestically and internationally, may have products that face rapid obsolescence, and are heavily dependent on the protection of patent and intellectual property rights. Such factors may adversely affect the profitability and value of video gaming companies. Investments made in small and mid-capitalization companies may be more volatile and less liquid due to limited resources or product lines and more sensitive to economic factors. Fund investments will be concentrated in an industry or group of industries, and the value of Fund shares may risk and fall more than diversified funds. Foreign investing involves social and political instability, market illiquidity, exchangerate fluctuation, high volatility and limited regulation risks. Emerging markets involve different and greater risks, as they are smaller, less liquid and more volatile than more developed countries. Depository Receipts involve risks similar to those associated investments in foreign securities, but may not provide a return that corresponds precisely with that of the underlying shares. Please see the prospectus for details of these and other risks. Roundhill Financial Inc. serves as the investment advisor. The Funds are distributed by Foreside Fund Services, LLC which is not affiliated with Roundhill Financial Inc., U.S. -

Huya Inc. NYSE: HUYA

Huya Inc. NYSE: HUYA Autoren dieser Analyse: Jan Fuhrmann "If you’re not failing, you’re not pushing your limits, and if you’re not pushing your limits, you’re not maximizing your potential." - Ray Dalio Christian Lämmle "Markets are never wrong, only opinions are.“ - Jesse Livermore 1. Das Unternehmen Kurzvorstellung In dieser Analyse haben wir die Huya Aktie WKN / ISIN A2JL12 / US44852D1081 unter die Lupe genommen. Huya ist im Branche Kommunikation (Entertainment) Bereich des Entertainments, genauer gesagt Einordnung (P. Lynch) Fast Grower im Live-Streaming-Markt für E-Sports tätig. WLA-Rating 7 / 10 Tencent wollte als größter Anteilseigner von Marktkapitalisierung 3,03 Mrd. USD Huya eine Fusion mit dem Konkurrenten Dividendenrendite 0,00 % DouYu herbeiführen (auch hier ist Tencent KGV 22,4 beteiligt), aber das chinesische Kartellamt durchkreuzte diesen Plan. Firmensitz Guangzhou (China) Die Aktie befindet sich auf Allzeittiefniveau und die Trends sind in jeder Zeiteinheit abwärtsgerichtet. Lediglich der langfristige Trend kann noch als neutral betrachtet werden. Die Analyse bezieht sich auf den Kenntnisstand unserer Recherche vom 28.07.2021. 1 Geschäftsmodell & Branche Allgemein Huya Inc ist eine führende Game-Live-Streaming-Plattform aus China. Der quasi einzige Konkurrent ist DouYu (die Fusion von DouYu und Huya unter den Augen von Tencent wurde erst zuletzt vom chinesischen Kartellamt gestoppt). Das Geschäftsmodell lässt sich mit dem im Westen eher bekannten Twitch.tv von Amazon Inc. vergleichen. Auf der Plattform kann im Grunde jede*r einen Stream hosten. Die meisten Streamer*innen zeigen Videospiele, es gibt aber auch Kochshows, "traditionelle" Sportarten und andere Formate. E-Sports Den Themenfokus der Streams hat Huya auf den in China (aber auch weltweit) immer populärer werdende E-Sports gelegt. -

A Model for Information Behavior Research on Social Live Streaming Services (Slsss)

A Model for Information Behavior Research on Social Live Streaming Services (SLSSs) Franziska Zimmer(&), Katrin Scheibe(&), and Wolfgang G. Stock Department of Information Science, Heinrich Heine University Düsseldorf, Düsseldorf, Germany {franziska.zimmer,katrin.scheibe}@hhu.de, [email protected] Abstract. Social live streaming services (SLSSs) are synchronous social media, which combine Live-TV with elements of Social Networking Services (SNSs) including a backchannel from the viewer to the streamer and among the viewers. Important research questions are: Why do people in their roles as producers, consumers and participants use SLSSs? What are their motives? How do they look for gratifications, and how will they obtain them? The aim of this article is to develop a heuristic theoretical model for the scientific description, analysis and explanation of users’ information behavior on SLSSs in order to gain better understanding of the communication patterns in real-time social media. Our theoretical framework makes use of the classical Lasswell formula of communication, the Uses and Gratifications theory of media usage as well as the Self-Determination theory. Albeit we constructed the model for under- standing user behavior on SLSSs it is (with small changes) suitable for all kinds of social media. Keywords: Social media Á Social live streaming service (SLSS) Live video Á Information behavior Á Users Á Lasswell formula Uses and gratifications theory Á Motivation Á Self-determination theory 1 Introduction: Information Behavior on SLSSs On social media, users act as prosumers [1], i.e. both as producers of content as well as its consumers [2]. Produsage [3] amalgamates active production and passive con- sumption of user-generated content. -

Cultivating Community: Presentation of Self Among Women Game Streamers in Singapore and the Philippines

Proceedings of the 54th Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences | 2021 Cultivating Community: Presentation of Self among Women Game Streamers in Singapore and the Philippines Katrina Paola B. Alvarez Vivian Hsueh-hua Chen Wee Kim Wee School Wee Kim Wee School of Communication & Information of Communication & Information Nanyang Technological University Nanyang Technological University [email protected] [email protected] Abstract explores how women game streamers in Southeast Asia manage their presentation of self [9] while This study explored how women game live cultivating a stable community of viewers and streamers in Singapore and the Philippines make navigating a medium perceived as dominated by North sense of their presentation of self as performers and American and European content creators, in a region gamers in a medium dominated by Western games, whose game industry and culture are also led by performers, and platforms. We conducted six in-depth foreign games [10][11]. interviews guided by interpretive phenomenological The presentation of self framework proposes that analysis in order to understand their experiences, social interactions can be understood as performance. uncovering issues such as audience connection and People engage in various practices in order to maintenance, the difficulties of presenting their own cultivate, manage, and manipulate others’ impressions femininity, and the influence of being Singaporean, of them, their actions, and the situation. Often, the Filipina, and Asian on their success as performers. We performed persona or presented self can be different discuss directions for study that further explore from the self that has no audience present [9]. As gaming and streaming as a form of cultural labor in researchers and streamers alike similarly view Asia.